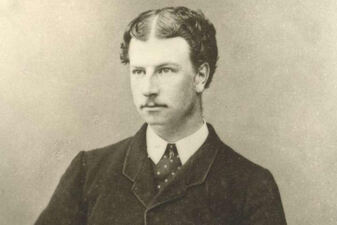

Henry Edward Dormer (1844–66) Henry Edward Dormer (1844–66) LONDON, ONTARIO – Gagging just a little on all the witless accounts wafting out of the States about their newly-installed houseplant of a president and his wonderfully devout Catholic faith, I have sought out some sanity-restoring refuge this week by re-immersing myself in the story and example of Henry Edward Dormer (1844–66). London’s only credible candidate for sainthood, Henry Dormer was a twenty-one year-old British Army ensign who only lived in our city for a grand total of 222 days – the last seven months of his life – but his selfless piety left such an indelible impression that he still inspires his adopted townspeople more than a century and a half later. The first London chapter of the Knights of Columbus which flourishes to this day calls itself the Dormer Assembly in his honour. The last artwork that Jack Chambers (1931-78) struggled to complete was his Dormer Memorial designed to be marketed as a limited edition print with proceeds going to help the cause of Dormer’s beatification. And to mark the 150th anniversary of his death, in 2016 Dormer House, a residence of discernment for young men contemplating the priesthood, was opened in the vicinity of St. Peter’s Seminary in north London. Henry Edward Dormer was born near Warwick, England in a glorious old pile called Grove Park which, Brideshead-style, came with its own private in-house chapel. Henry was the fourth son and youngest child of a well-positioned recusant Catholic family. Henry’s father Joseph Thaddeus was titled the 11th Baron Dormer and the family had provided generations of service, military and otherwise, to the Tudor and Stuart monarchies. Removed from the Catholic military college of St. Mary’s in Oscott when he contracted rheumatic fever at the age of twelve, Dormer was taught at home for a couple of years and then spent five years receiving private instruction from tutors in Belgium, Germany and Ireland. At the age of nineteen he returned to Oscott where he concluded his military training and that was when Dormer’s faith was dramatically deepened following a retreat he made under the instruction of a Dominican friar named Father Rudolph Suffield. Though Dormer was starting to think of giving his life entirely to Christ, he didn't have the personal resolve to resist the tide of longstanding family tradition and after passing his final exams in 1863, he was gazetted as an ensign in the 4th Battalion of the 60th Regiment of the King’s Own Royal Rifles. Then, upon completion of a term of basic training in Winchester, Dormer was posted overseas to the military garrison that was then set up in what is now Victoria Park in the heart of downtown London. Full of misgivings and doubts that the military life was what he was put on this earth to fulfill, Henry Edward Dormer arrived in London on February 22, 1866. The British Army had commenced its thirty-year residence in London in response to the December Rebellion of 1837. At that anxious moment in colonial history, many of the supporters of William Lyon Mackenzie and St. Thomas radical Dr. Charles Duncombe, fled south across the border to the northernmost States from where it was thought they posed a significant threat to the communities in the southwestern peninsula of Canada West which stretched from London down to Windsor (or Sandwich as it was then called). By the time Henry Dormer arrived here, that threat had passed and the new bogeyman - which also turned out to be a pretty damp squib - was the possibility of Fenian raids in the discombobulated wake of the American Civil War. When the garrison was originally established here in 1838, London was a struggling district town with a population of 1300. So the addition of 400 British troops and their dependents (all of whom needed to be regularly provisioned by local merchants and suppliers) was a real boon to London’s early development, both economically and culturally. Many garrison soldiers and virtually all of their officers were well-educated men and when they weren't exactly run off their feet with quelling rebellions, they were able to turn their ample energies to recreational pursuits; starting up amateur theatres and choirs and athletic teams. London's first sports field - a cricket pitch - was laid out on the garrison grounds. Some of the better born men of the garrison were also coveted as potential husbands for the daughters of London's wealthier families. Many dances and dinners - with nubile London lasses in low cut Regency gowns ladling out the punch - were arranged to help facilitate such mergers. Most notoriously, the over-daughtered Harris family of Eldon House would eventually nab no less than four officers in matrimony. Wealthy and handsome as Henry Dormer was, he was more or less oblivious to such local charms and amenities when he arrived here just in time for the mucky misery of a late winter thaw. He wrote an early letter home to his mother which strikes an uncharacteristically whiny note: “I am afraid there is not much exaggeration in the abusive account everyone gives to this place. It has positively no resources of its own, no shooting, no fishing, no skating, and a very indifferent society, no libraries, no clubs and no walks except a high road up to your knees in mud.” Perhaps all that atypical letter really tells us is that Henry wasn't yet ready to tell his parents the direction in which his heart was inclining. In the couple years preceding his trans-Atlantic trek, Dormer’s sense of religious commitment had radically deepened. Always a notably kind soul concerned with the well-being of others, he had recently pledged himself to the lifelong care of a young orphan. And en-route to his embarkation to Canada West, he paid a farewell visit to his beloved sister, Agnes Philomena, who was just beginning her life as a Dominican nun at Stone Priory in Staffordshire where she eventually became Prioress. Once in London, he wrote her that he was a changed man: “From the moment I left Stone, after having had the inestimable blessing of making my peace with God, I have had a kind of resolution in my mind to abandon the world and join a religious order.” After his military duties were carried out each day, Dormer could be found in a quiet ecstasy of prayer either at St. Peter’s Church immediately west of the garrison or in the chapel of the Sacred Heart Convent several block to the east. The priests at the church let him know where they stashed a key and he often slipped in after dark to spend the entire night in prayer before the blessed sacrament. Dormer also attended selflessly to London’s poor and sick and would accompany the priests as they carried the Eucharist to shut-ins. He became a mainstay in the charitable operations of the St. Vincent de Paul Society, donating not just his time and his care but also money, food and his own clothing. He served as a teacher to the children at St. Peter’s Church on Sundays and also gave religious instruction to his fellow soldiers and officers if they requested it. As a result of his care-taking visit to a woman with typhoid fever in late September, Dormer himself swiftly succumbed to the disease. The finest chronicler of London's pioneering decades is that great civic matriarch, Amelia Ryerse Harris, and she did mention Henry Dormer once on the occasion of his passing. Though this entry was not included in the selection of The Eldon House Diaries published by the Champlain Society in 1994 - not Anglican enough to make the final cut, I'm guessing - historian and curator Mike Baker flagged it in a worthy, if slightly indulgent, documentary from 2008, The Saint is Dead that was produced by David Belne and Peter J. Adams. October 1, 1866 I got a note from Captain Williamson asking for some beef tea and jelly for poor young Dormer of the 60th who is very ill. He is a Roman Catholic and has fasted and done penance and scourged himself until his life is despaired of. He is only 22 or 23 years of age. October 2 Mr. Dormer died this morning. It is gratifying that Dormer registered for at least a moment on Amelia's consciousness and it is also very telling of the prejudices of the time that she didn't think to mention 'typhoid' among the contributory causes of his death. I mean sure, he went in for a few of those disciplinary exercises, common in Catholic circles at that time, which have always drained the colour from Protestant complexions. But for goodness' sake, the man didn't flay himself to death. Making good on the determination expressed in that letter to his sister, Dormer had recently submitted his resignation to the army and was simultaneously waiting to hear whether he would be accepted into the Dominican friars. Theodore Smeenk was a long-serving Knight of Columbus in the Dormer Assembly who did more than anyone else through the middle decades of the twentieth century to keep Henry Dormer's flame aglow. In one of his many talks and essays about Dormer, he came up with an inspired turn of phrase to describe the affiliative status of the young ensign at the time of his death: “Dormer’s release from the army was in the mail and reached London on the morning of his death. He died between the uniform of his Queen and the uniform of his Lord.” The very last words in that documentary cited above go to the late Bishop John Michael Sherlock who similarly addresses this rather haunting idea of Dormer as the bold supplicant who does not need to be formally accepted into any organization in order to accomplish his work. "Henry Edward Dormer didn't have much time. But the time he had he used with extraordinary grace and generosity. He didn't have to be ordained to give himself to God. He had done that and God accepted him." Less than two weeks after Dormer's death, Father Byrne, the superior of the Dominican friars in Louisville, Kentucky who then staffed London’s only Catholic church, wrote to Dormer’s parents: “I was the first priest whose acquaintance he formed in America, and the last who saw him while reason still remained on earth. In all the sincerity of my soul I believe, my dear Lord and Lady, that you have brought into the world and reared to manhood a great saint.” In 1922 the Bishop of London, Michael Frances Fallon, had the honour and pleasure of writing to Dormer’s sister at the Dominican convent in Stone, that “carefully and prudently” he was undertaking to set in motion the famously slow process of canonization for her brother. Ninety-nine years later, still maintaining that leisurely and indeed geological pace, that process continues to this day. Supporters thought there was a better-than-usual chance that the cause might really take flight in October of 1966, on the hundredth anniversary of Dormer's death when the tireless Theodore Smeenk and the Dormer Centenary Committee choreographed a massive celebration with church, government, and military dignitaries in attendance. There was a special mass at St. Peter's Cathedral Basilica and a re-interment ceremony for Dormer's bodily remains at St. Peter's Cemetery. Quite poignantly that great old Catholic warrior Governor-General Georges Vanier turned out with his wife, Lady Pauline Vanier, to pay tribute to this remarkable young soldier.from a century before. It was, in fact, Vanier's last official public appearance before his own death five months and three days later.. In 1970 Smeenk and the Committee worked with the University of Windsor Press to publish a limited edition of a two-hundred page compendium of writings about Dormer by various hands including Smeenk himself; Father V. Ambrose McInnes who worked with Jack Chambers on the Dormer Memorial project; Father Joseph Finn who took over from Smeenk as the London Diocese's foremost proponent of Dormer's canonization; and Rev. Mother Francis Raphael Drane of the Dominican Convent in Stone who worked with Dormer's sister in producing a hundred page memoir of Dormer - originally published in 1867 and presenting the most detailed account of his life which we have - which is reproduced in this collection in facsimile form. I never even knew this goldmine of a volume existed until I happened upon it for a dollar at a church rummage sale, complete with a presentation copy sticker on the flyleaf inscribed to my favourite London historian, Orlo Miller (1911-93). At my home parish of St. Peter's Cathedral there's an exquisite stone plaque on the north wall of the west transept which I pass while processing to receive the Eucharist on those days when I serve as a reader. The carved letters on the face of the plaque read: Sacred to the memory of Hon. Henry Edward Dormer Born at Warwick Grove Park Nov. 29, 1844 Died at London, C.W. October 2, 1866 Requiescat in Pace The plaque was given to the old St. Peter's Church by the men in Dormer's regiment shortly after his death and then went missing when the current cathedral was being built on another section of the same property from 1880 to '85. It turned up ninety years later when archivist Ed Phelps was informed that there was this really old looking tombstone thing that was being used - face down, no less - as a back door stoop for a private house on Cheapside Street. Ed didn't quite know what to make of it until he showed it to Catholic historian, Dan Brock, who assured him this was a major find. The plaque was cleaned up and restored and set in its present place of honour in 1975. When and if the push for Dormer's canonization really goes forward, I might suggest the rescue of this plaque should serve as one of his requisite miracles. And if they need a second one, then how about the fact that we easily distracted denizens of a heedless age and a history-averse city have somehow been able to remember and revere this dear and holy man for more than a hundred and fifty years? And really, when you get down to it, who needs all that high church folderol anyway? In the same way as Bishop Sherlock suggested that Dormer didn't have to be ordained to be accepted by God, I say canonize away in your own sweet time, you Vatican clerics, and we'll send up a great hurrah when you do. But in the meanwhile, Henry Edward Dormer has already won his place in Catholic London's heart as our saint. SOME RELATED HERMANEUTICS READINGS: For more on Amelia Harris: Bright Spirit of Eldon House (August 19, 2018) For an account of Governor General George Vanier's life: Governance by Grown-Ups (January 21, 2020) A memoir of the man who rescued Dormer's plaque from oblivion: My Publisher, Ed Phelps (January 10, 2021)

4 Comments

Jim Chapman

25/1/2021 11:14:53 am

"damp squib"!! Marvellous!

Reply

Ninian Mallamphy

26/1/2021 04:43:56 pm

I get the impression that Herman would be quite content if the saintliness of Henry Edward Dormer were an aspect of congregational veneration rather than of Canonization--as was the case in the European church before the eleventh century. Saintly abbots and bishops in Ireland were venerated as saints soon after death. Think of St.Patrick. Who canonized him? And there was a Maolanfaidh, who founded a monastery at DairInish, near the mouth of the Munster Blackwater river around 555 A.D., whose feast day we celebrate on January 30 ---- and who may have been the only holy person in the history of my family. I have already lined up the admirable Dormer with him and with the popular saints of the first thousand years of Christianity. I know that Herman approves.

Reply

Max Lucchesi

29/1/2021 12:46:33 am

Well well, you begin a post on sanctity by insulting a man only because he replaced a president you admire. A man who paid hush money to a porn star not to publicise his extra marital affair. A man who though had won the electoral college, his ego refused to accept the loss of the popular vote, so lied, blaming the fraudulent votes cast by millions of unregistered illegals. After inauguration he lied again stating the crowds attending his inauguration were larger than Obama's. Small beer perhaps but it set the tone for an administration who's only function was to pander to his narcissism.

Reply

Dan Brock

8/2/2021 11:53:51 am

Hi Herman, Thanks. I got to read the Dormer blog today. Very fine background research. And yes, I learned a few things about Dormer I didn’t know before. I was at the ceremony in 1967 at the southwest corner of St. Peter’s Cemetery. Dan

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed