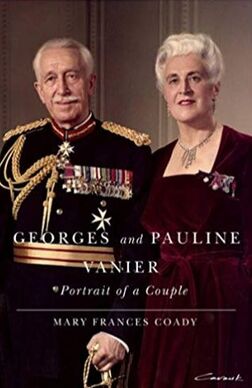

LONDON, ONTARIO – “My goodness, why is he reading that right now?” my wife sometimes wonders when she sees me go digging through a book so apparently eccentric or retrograde or unconnected to the sort of fare that usually beckons my interest, that its appeal utterly stumps her. But recognizing the powerful influence which she uniquely exerts on my consciousness, she usually manages to muffle such questions for a while at least. Stuffed to the brim with prudential wisdom, she understands that – with reading as with writing – a word of discouragement or bewilderment that is voiced too soon may jinx the possibility of worthwhile engagement and exploration. Such was the case over the Christmas holidays as I ravenously read Mary Frances Coady’s 2011 book, Georges and Pauline Vanier: Portrait of a Couple. For sure this biography of one of Canada’s most popular Governor-Generals (1959–67) was not a customary selection for one who ordinarily finds the study of contemporary Canadian politics magically unengaging and soporific.

In the wake of last October’s federal election when a vain and vacuous ex-drama teacher with a famous last name was inexplicably re-elected to the office of prime minister, I badly needed this restorative vacation in early and mid-20th century Canada; a time when - despite whatever flaws may have otherwise troubled them - our statesmen and political leaders at least made the attempt to comport themselves as adults. In election after election – be it national, provincial or civic – I am benumbed by the unfailing Canadian genius for refusing to grasp the nettle of any discussion worth having at a time when contenders for public office are supposed to be able to argue positions in an open season of free-ranging political discussion. Though Kim Campbell's words helped sink her 1993 bid to electorally secure the post she’d just been appointed to, it seems that all parties took those words to heart when our first and fleeting female prime minister irritably opined that, “An election is no time to discuss serious issues.” “You just don’t get it,” I and my fellow secessionists from the zeitgeist are told as we wearily shake our heads at the insipid political incoherence of our time. And they’re right. We don’t get it. Indeed we question whether there is anything to get (except in the sense that one becomes sickened by ‘getting’ the flu) about a prime minister who professes to be Catholic while flagrantly denying several of the Church’s central tenets and forbidding any MP in his party to openly uphold them either. I happened upon Coady’s book in that little shop that’s run by the Friends of the Library in the northern block of Citi Plaza. Its bargain basement price of three dollars was part of its attraction but more alluring yet as I sampled random paragraphs to get a sense of the book’s subjects and the tenor of Coady’s prose, was the impression immediately conveyed that there was a time not all that long ago – certainly within the span of my own life – when a man of serious accomplishment, conspicuous courage and devout faith could hold an office of high honour in this land and nobody but a handful of separatist hotheads found him ‘problematic’. What the separatists couldn’t stomach was Vanier’s consistent, full-throated advocacy of national unity which is expressed in this excerpt from one of his final speeches: “The road of unity is the road of love: love of one's country and faith in its future will give new direction and purpose to our lives, lift us above our domestic quarrels, and unite us in dedication to the common good. We can't run the risk of this great country falling into pieces . . . The measure of Canadian unity has been the measure of our success. If we imagine we can go our separate ways within our country, if we exaggerate our differences or revel in contentions … we will promote our own destruction. Canada owes it to the world to remain united, for no lesson is more badly needed than the one our unity can supply: the lesson that diversity need not be the cause for conflict, but, on the contrary, may lead to richer and nobler living. I pray to God that we may go forward hand in hand.” Of course, by the separatists’ dim light, blind to any notion of common purpose or duty and seeking only the advancement of their own narrowly defined kind, such generous sentiments made Vanier a "sellout" and a "jester of the Queen". “The past is a foreign country,” L.P. Hartley wrote in the opening lines of his most highly regarded novel, The Go-Between. “They do things differently there.” Well, it was only 61 years ago in a profoundly foreign land called Canada that Georges Vanier took the oath of office as the second Canadian-born and first Quebec-born Governor General, and opened his address to Parliament in a ceremony overseen by Queen Elizabeth II, by saying: “My first words are a prayer. May almighty God in His infinite wisdom and mercy bless the sacred mission which has been entrusted to me by Her Majesty the Queen and help me to fulfill it in all humility. In exchange for His strength, I offer Him my weakness. May He give peace to this beloved land of ours and the grace of mutual understanding, respect and love.” Born in Montreal in 1888, Georges Phileas Vanier’s devotion to God and country were evident throughout his life. He was remarkably adept and capable in academic studies and athletics, was fluently bilingual from a very young age, and was so well-adjusted and magnanimous that he managed to win the respect of his teachers, the worshipful adoration of his siblings and the affection of his peers. He was also a daily communicant at Mass and recurrently contemplated becoming a priest. But the call he most consistently discerned was one of duty to his country and when the First World War broke out in 1914, he stepped away from his junior position with a Montreal law firm and immediately enlisted and helped organize the very first French Canadian battalion: the Royal 22nd Regiment or Van Doos. Vanier saw action in many battles - including those at St. Eloi Craters and Vimy Ridge - and among the chestful of medals he'd win for his courageous leadership were the Military Cross and the Distinguished Service Order. Fatalistic about the risks entailed in his service, he once wrote home to his parents, “I sleep as ever on the fresh earth. One day we shall all go back to her.” Yet when he did almost buy the farm during the Canadian Corps’ heroic Hundred Days campaign in the summer of 1918, Vanier took his sweet time informing his parents just how extensive his injuries were. Coady writes of that fateful skirmish: “Georges led his battalion and almost immediately received a bullet in his right side. As a stretcher-bearer was dressing the wound, a shell burst beside them, killing the stretcher bearer and shattering Georges’ legs. ‘This was to be one of my bad days,’ he wrote to his mother some time later. It was worse than bad. It was the end of Georges Vanier’s war. The date was 28 August, a day that would have significance for the rest of his life. In seventy-four days the Great War would end.” Vanier’s family knew that his legs had been injured but did not know that his right leg had to be amputated above the knee. “My present state is more than satisfactory,” he wrote home. “Temperature and pulse normal, sleep coming back to me etc. I am really making rapid strides to complete recovery. Remember there is NO CAUSE FOR WORRY.” After a month of recuperation had restored what could be restored, he flatly refused to be sent home on the grounds that, “I simply cannot go back to Canada while my comrades are still in the trenches in France.” One suspects that another reason for hanging back was to spare his family the full and awful truth at a time when he was still struggling to come to terms with it himself. In one of the more psychologically probing sections of her book, Coady examines Vanier’s decision to not leave matters military behind after the war: “Others were to return home and write about torn limbs and headless bodies and mumbling exhaustion and the frightened eyes of enemy soldiers whom they recognized as human like themselves. Georges had seen it all too. As the war had continued to claim young men by the thousands, commanders in the field often seriously questioned the strategies and tactics of the high command, and he may have questioned them himself. Yet there is no written evidence of such criticism from him. In fact, when the conflict was all over and others turned their backs on the army, he would eagerly choose it once again. Perhaps the extremity of his situation for three years – the stripping down to bare essentials, the primitive trench life, the daily fear – brought him a clarity, a sense of purpose that on a deep level he knew he could not have achieved in any other way. Mystery and paradox lie at the heart of every human life, and perhaps this is the only answer to why Georges Vanier, a man of peace and poetry and contemplation, was to continue embracing the military life.” In 1921 Vanier was reunited with Julian Byng, the British General who had overseen the Canadian Corps at Vimy Ridge, when he became aide-de-camp during Byng’s term as Canadian Governor General. And in that same year he married Pauline Archer with whom he would father five children, including Jean - who died just last year at the age of 91 - a Catholic writer and theologian who started up L'Arche; a highly regarded international movement of caring communities for people with developmental disabilities. His marriage to Pauline was something that Georges Vanier scarcely hoped for. Once before in his life, while contemplating a life in the priesthood, he’d been prepared to forgo the prospect of ever marrying. And in the wake of his amputation he wondered once again if it would be possible for those particular stars to ever align for him. Would any woman ever be able to show that kind of interest in him? Coady quotes a profoundly moving letter Vanier wrote to Pauline on the fifteenth anniversary of their wedding: “In marrying me, you restored my confidence in myself. You gave me a clear indication, and it was obvious you meant it, that you didn’t in the least consider me physically diminished. When you agreed to marry me, bursting with open-hearted sincerity, you confirmed me in my dignity, in my pride, and perhaps also in my vanity as a man . . . I thank you for your love, your help, your example, for the gift of your whole being.” After Byng’s Governor Generalship wrapped up, Vanier took up the post of commander to his old Van Doos regiment from 1926 to 1928. And from then until the end of his life, he would move from one military, diplomatic or ministerial appointment to another, serving in Canada, France and Britain. And in all of these positions it was quickly understood that Georges and Pauline were a two-for-the-price-of-one deal; you took them as a team or you didn’t get either. The list of appointments the Vaniers filled is too extensive and convoluted to go into here but there were many moments of high drama and uniquely enlightened service, particularly around the time of the Second World War. Georges was the Canadian minister to France when the Nazis marched into Paris in 1940 and he and Pauline oversaw the evacuation of Canadian citizens and other desperate refugees to England before heading out themselves. Pauline left with the kids and her mom on a cargo boat while Georges hung back for one more week, making his escape at the very last minute with two other diplomats. They drove to Bordeaux just ahead of the invading army where Georges was able to wangle a series of lifts to Plymouth - first on a small and incredibly smelly sardine boat (comically named Le Cygne or The Swan), then on a Canadian destroyer HMCS Fraser (which was sunk by a German mine four days later) and finally a British cruiser, Galatea. To board Galatea he had to scramble his way up a swaying rope ladder, which takes some doing even when one of your legs isn't wooden. Describing that last link of his 18-hour relay of escape, Vanier wrote: "That cruiser turned its nose toward England, and like a horse that smells its stable, just went hell for leather. It just didn't give a damn for waves, nor mines, nor torpedoes, nor planes." Coady says, that Vanier’s love for France was "tinged with a sense of the sacred." He was devastated by the speed with which France fell but unlike nearly all of his colleagues in the diplomatic community, he was immediately suspicious of the puppet regime put in place by the Germans; the so-called Vichy government. He counseled the Allied governments to instead give their support to French General Charles de Gaulle who was recruiting a free French army from his base in London. His warning was initially dismissed and Vanier was temporarily demoted to a lesser posting. But it didn't take long for the Vichy traitors to show their true colours and Vanier was called back to London where he worked with de Gaulle as the minister to the Allied governments in exile. Then, in the sweetest vindication of all, in 1944 Vanier was appointed Canada's ambassador to France and was the very first diplomat to enter Paris after the liberation. Though the arrogant de Gaulle would later prove himself to be an ungrateful shit, snubbing both Vanier and Canada after they'd made such efforts on behalf of the Free French cause, Vanier, as ever, took the high road and never publicly expressed his disappointment. Another of Vanier's astute wartime suggestions which also was lamentably ignored, was a 1940 memo to Prime Minister McKenzie King urging Canada to take in Jewish refugees who were desperate to elude the Nazis: “Canada has a wonderful opportunity to be generous and yet profit by accepting some of these people,” he wrote. I wonder if McKenzie King remembered Vanier's letter in the spring of 1945 when the death camps were finally liberated? Vanier himself toured Buchenwald that April and gave a rueful report on CBC Radio in which he had the humility to include himself among the negligent who had signally failed to do enough to help innocent people in perilous need: “How deaf we were then, to cruelty and the cries of pain which came to our ears, grim forerunners of the mass torture and murders which were to follow.” I'm just realizing today that one of the reasons I picked up Coady's book is the trace memory I retain of the spontaneous testimony my mother made when we heard the report - was it radio or TV? - of Georges Vanier's death. All I really recall is her voice. "Oh, he was a beautiful man," she said with a note of real loss. A wise judge of character, I think she used the very same words - and maybe more than once - to describe Duke Ellington. And shortly after she died I made a point of reading Terry Teachout's biography of a jazz composer I didn't really know or care about just for the sense of communion that can be derived by contemplating the subject of a loved one's esteem. It was early in Canada's centennial year when the 79 year-old Governor General sensed that he just wasn't up to the especially heavy load of speechifying and ribbon-cutting that was going to be required in the months ahead. His energy and health were clearly failing; there were days he scarcely got out of bed. His last few speeches had been delivered from a wheel chair; a necessity he found galling. The prime minister knew of his misgivings and Lester B. Pearson dispatched a renowned heart specialist from Boston to examine his friend. This doctor's opinion was that it would put too great a strain on Vanier's heart to continue. Pearson dropped around Rideau Hall on the evening of Saturday, March 4th to float the idea that perhaps Vanier could take on a less demanding role for the rest of the Centennial year. He suggested that Vanier might move back to Quebec and become the keeper of the Citadel. Nope, it would be better to make a clean break of it and call it a day, Vanier decided. But as long as you're here . . . . and then the pair of them snapped on the TV and watched the Montreal Canadiens clobber the Detroit Red Wings on Hockey Night in Canada. Here is Coady's account of the next morning: "Sometime earlier, Dr. Burton and [Vanier's personal attendant] Sergeant Chevrier had moved [Georges] from his own bedroom to a room across from the chapel [which, along with an elevator, had been installed when the Vaniers moved into Rideau Hall]. Sergeant Chevrier affixed a mirror in the doorway in such a way that from his bed the invalid could see the altar. Sunday, 5 March, was 'Laetare' (Latin for 'rejoice') Sunday, marking the mid-point of Lent, when the Scripture readings, breaking the usual sombre Lenten pattern, sound a note of joy. The chaplain, Father Hermas Guindon arrived at ten thirty for morning Mass. Pauline was already in the bedroom with her husband, as were their sons Jean, who had come to Canada on a lecture tour, and Michel. Dr. Burton had also arrived. Father Guindon brought communion, and then Pauline and her sons went into the chapel for Mass. When the patient indicated that his oxygen mask was irritating and tried to remove it, Sergeant Chevrier wiped it out and then gently replaced it and gave him a sip of water. Georges said a faint 'Merci'. By the time his family returned to his bedside, he was already dying. Dr. Burton felt his pulse becoming increasingly weaker, and quietly announced at eleven twenty-two that he was dead." About five years after Georges' death, Pauline went to live - and to help out in any ways that she could - at her son Jean's original L'Arche community in Trosly-Breuil, northeast of Paris. She had her own small house on the grounds but it took her a few weeks to get comfortable with such a sweeping change in her entire way of life. A pivotal moment in making that transition occurred one day when she was suddenly overcome by a desolating sense of dislocation and slipped into the chapel where she had herself a good, drenching and - she thought, solitary - cry. Then, Coady writes, "she felt a hand on her shoulder. She looked up to see a mentally handicapped man from one of the foyers. Without speaking, he took her hand and led her silently out of the chapel and to the door of her home. This small gesture was to be one of many upside-down lessons of unconditional acceptance she would learn in what she called ‘the school of L’Arche’ during the coming years.” * In the week after I finished reading this eye-wateringly nostalgic portrait of a uniquely capable statesman who never pandered to ideological factions nor sought to squelch the conscience rights of anyone nor failed to uphold those religious convictions which informed his every action and decision, there was a sudden inane flutter in the national media which put everything in context for me. Our pajama-boy of a prime minister returned from his nearly three-week Christmas . . . oops, I mean winter . . . break in Costa Rica, sporting a grey flecked beard to offset his dreamy head of hair. And voila, all those government-subsidized newshounds in our failing print and broadcast media played it up like a moon landing or a just-discovered cure for cancer; many of them gushing or purring that this latest follicular accoutrement made him appear ever so much more "statesmanlike”. Yes, I remembered. The year is 2020 and we are governed by narcissistic infants.

1 Comment

Max Lucchesi

25/1/2020 06:03:19 am

Excellent piece Herman, though the extraordinary courage shown by the Canadians during W.W.1 was duplicated during W.W.2 at the battle for the Liri Valley and Monte Cassino, the advance along the Adriatic Coast in Italy From Juno Beach to the Falaise Pocket in Normandy. The unbelievable hardships endured during the battle for the Scheldt Estuary and Walcheren Island in Holland. You are so right in your observation that our politicians are Narcissistic infants, I know you include, as I do, President Trump and my own Prime Minister Boris Johnson on your list.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed