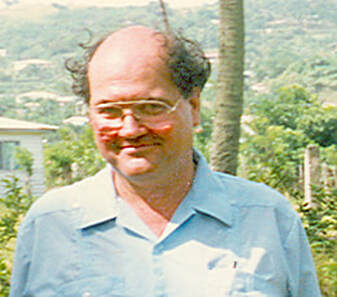

Ed Phelps (1939 – 2006) Ed Phelps (1939 – 2006) LONDON, ONTARIO – About fifteen months ago I was invited to contribute an essay for a sort of Festschrift which is being compiled to commemorate the life and work of local historian, archivist, librarian and publisher, Ed Phelps (1939–2006). I feared I was actually running a little late when I dispatched this piece to the editor precisely one year ago and was surprised to be told that I was actually the first to send his contribution along and that perhaps my sterling example would now inspire the other contributors to step up their pace a little. Not for the first time I shook my head in bemused admiration for just how elastic the concept of a deadline can be in the scholarly/academic world. Some other contributions have drifted into the editor over the last twelve months while others are still being pulled together as we speak. Will 2021 be the year that this opus has its rendezvous with the publisher? Let us hope so. And in the meanwhile, consider this memoir of what it was like to publish three books under the aegis of Ed Phelps to be a scintillating preview...

AS A LONDON-BORN London-tethered and largely London-focussed writer for the last fifty years, I have often lamented the fact that this town has never had a real publishing house. Apart from the very occasional independent start-ups that struggle to make a go of it for a few years and then quietly expire (such as Mac and Jill Jamieson’s Applegarth Follies and Win and Linda Schell’s Ergo Press) – and unlike just about every other university city in the province of comparable size and vintage – London has never been home to a reliable, enduring, broad-based book publisher. After Applegarth published my first novel in 1975 and then thrust my second novel into limbo the very next year by fleeing town in bankruptcy before they could either publish it or think to release me from our legally binding contract to do so, I realized it was time to rethink just how I intended to eke out any sort of living as a writer. With the collapse of any proximate prospect of getting fiction published, and the rising responsibilities of marriage and fatherhood, I necessarily switched my main literary focus to journalism which I had reason to believe might actually pay. And it did. As compared to the profits I’d scarcely realized from fiction, journalism was a veritable goldmine. And I was delighted to discover that the switchover didn’t seem to inflict that much disruption on my literary instincts. I still got to plug away at fiction on the side and because I was always a self-directed freelance journalist, I never got saddled with assignments that didn’t genuinely interest me and found ready homes for essays, reviews and features in The London Free Press and more than a dozen other area magazines and papers. Someone who seemed to agree that I wasn’t utterly wasting my talent in journalism was a certain Ed Phelps who made his entrance into my life via telephone, late one night in 1986. I remember the lateness because, although I’ve been a night owl most of my life, I was cognizant of the universal imperative that if you aren’t a relative or a good friend with a truly urgent bulletin, you aren’t supposed to call people after about ten p.m. (Indeed, that’s why I keep those hours; to secure an uninterrupted stretch of time to get on with my work.) So I was impressed that anybody would make a cold call – a ‘get acquainted’ call – at 10:45 p.m. Ed told me that he’d been reading a lot of my stuff and really enjoying it; so I was inclined to like him right away and was happy to answer his questions as we chatted away for the better part of an hour. Though he was perfectly lucid and bracingly acerbic at times, an increased profanity quotient in his language whenever he got excited made me suspect that he might have knocked back a few alcoholic beverages before looking up my number in the phone book. I was also pretty certain that he was fishing for something. Quite often when a call came out of the blue like that from a forceful personality, it was because they wanted me to write about them; a suggestion I almost always found resistible. So full points to Ed for originality; he said he’d published a number of books on local historical subjects and might be interested in bringing out a collection of my essays. I understood why Ed was hedging his bets with that “might be interested” clause when - during the single most profanity-laced section of our dialogue - he told me how the Phelps Publishing Company had taken a bit of a bath in 1977 by printing up a not very compelling volume by Wilfred L. Bishop entitled, Men and Pork Chops: A History of the Ontario Pork Producers Marketing Board. I know; it sounds like a title you might invent if challenged to dream up the most boring book imaginable. But it really existed and still projects some ghostly emanations to this day. Sometimes when I’m in a bit of a mood, I’ll look it up on Amazon just to see how it’s doing and usually find that it’s “currently unavailable”, that there is “no image available” of its cover, and that – would you believe it? – “there are no customer reviews”. Clearly, that little porker was going to be a challenging tome to move under the best of circumstances but whatever dim prospects it may have had were obliterated when Mr. Bishop himself expired while – in tragic contrast to their author – the pages of Men and Pork Chops were still warm from the printers. It was a good few months until I heard from Ed again and during that interim I undertook a little research to see how it could be that an avid reader of local writing such as myself (not to mention a writer ever on the lookout for possible publishers) had never heard of the Phelps Publishing Company. I discovered that he had published a really unappetizing 1980 volume with a butt ugly jacket that I’d actually seen at Robert’s Holmes Book Shop, quickly scanned and put back on the shelf as way too turgid for my tastes: A History of the London Police Force: 125 Years of Police Service 1855–1980. There might’ve been a way to tell that story with a little crackle and zip but a ten or fifteen-minute peruse was enough for me to ascertain that Ed and his author, Charles Addington, hadn’t found it. And over at The London Room of the Central Library, I discovered that Ed had more recently co-edited (but not published) an even more inert, two-volume opus called Wills of Elgin County, A Selection, 1846-1852. An introductory note to that work read, “This volume marks the first of a planned series of publications by the Elgin County Library, of Wills, Will Indexes, and Abstracts of Wills of residents of Elgin County from the earliest known documents up to the year 1900.” Just leafing through its muddily reproduced pages, I could feel my eyelids gaining weight and wondered if it was necessary to rip into one’s chest to stimulate a dangerously ebbing pulse or would thumping on the ribcage to the left of the sternum suffice? As head of the Regional Collection at UWO’s D.B. Weldon Library for twenty years where he had personally amassed an enormous collection of archives and artifacts pertinent to the history of southwestern Ontario – and as a publisher who had so far only been moved to publish rhetorically arid chronicles of what struck me as the most unenticing arcana – it became clear that Ed and I really weren’t on the same page when it came to our literary enthusiasms. It could be, I supposed, that Ed contacted me because he was looking to branch out into a whole new field. But as the weeks and months stretched out with no follow-up call, I began to suspect that Ed was entertaining second thoughts about his impulsive overture, had returned to his right mind, and I would never hear from him again. But then at least six months later I took another garrulous, late night call in which he said he’d decided to proceed with publishing a book and we arranged for him to come over to my house for our first face-to-face confab. Meeting him in the flesh and in the daylight was, I must say, a revelation. I hadn’t known Ed for very long but I’d had enough time to build up a mental image of him which couldn’t have been more wrong. That pushy personality which he shoved through the telephone wire with such reckless élan was toned right down in person. When it came to social manner and temperament, he was disarmingly polite and discreet; even shy in a strangely touching way. I don’t remember if he actually blushed during that first meeting or if I just sensed that he might be that rarest kind of adult who still could. But his courteous demeanor during our first face-to-face encounter (which is to say, that changed later when he got to know me better) was completely at odds with his spectacularly slobby physical presentation. My publisher-to-be looked more like a down-at-the-heels plumber than a librarian. I fully recognized and sympathized with what he was up against here. I’m a pretty chubby chap myself but when meeting with clients in a professional context, I am mindful of certain measures that guys like us can take to somewhat minimize the horror. But Ed was the original walking, talking unmade bed; complete with explosions of dark scrubbing-pad hair sticking out to either side of his bald dome and a t-shirt that rode up over the mound of his belly, revealing a smile-shaped roll of blubber that spilled over his belt-line like a generous slice of pink melon. “Yeh,” said his friend and frequent archive-diving assistant, George Fenner, laughing when I described that first physical sighting and then releasing an affection-laced sigh: “Clothes were a real impediment for Ed.” For three years running, 1987–89, I published three books with Ed which always came out in the fall. The first one, The Invisible Lone Ranger Suit, and the third, Towards a Forest City Mythology, were collections of essays and features. The second one, my own personal favourite of the lot, Counting Backwards from a Hundred, was a collection of short fiction. I know the print run for the first was 500 copies and I think he doubled that for the other two. All of them had a retail price of about ten bucks a pop. Because his own time commitments elsewhere were extensive and also (I’m conjecturing here but I think it’s fair to say) because my kind of writing was outside his usual bailiwick of expertise, Ed had me work with two of his colleagues, David Hallam and Catherine Ross in preparing the books for the press. They both had input in all areas of our discussions but David’s particular focus was the physical production and Catherine’s was editorial. Early on in the compiling of the fiction collection, Catherine told me that Ed was exercising his veto rights on one of the proposed stories which was entitled, When Friends Weigh Fifteen Tons and Neither Can Pay the Toll. He found it too depressing, she said. She may even have used the word “upsetting’. I was disappointed by Ed’s reaction but not entirely surprised. It was the tale of a wildly dysfunctional romance between two people with a magical capacity to bring out the very worst in each other and a few of the friends I’d shared it with found it pretty heavy-going too. I’d wanted to include it for the sake of stylistic contrast and displaying my range but acquiesced to Ed’s call without sulking. Later on as I attained a few glimpses into the sordid chaos of Ed’s personal life, I wondered if the real source of his objection to the tale wasn’t a matter of, “No thanks, I’ve got plenty of this at home.” “Not one damn cent in government aid,” was the letterhead slogan on Phelps Publishing Company stationery. Not too surprisingly then, there was no advertising budget for any of our projects. We did not have splashy book launch parties. We did not distribute our books to, or receive reviews from, any locality outside the boundaries of Middlesex County. Ed took care of getting our books out to whatever publications might review them and he kept the local bookstores stocked. I calculate that I personally sold about a third to a half of each print run by flogging them at readings and talks and always having a few copies of our latest title in my backpack as I made my daily rounds. I kept all the money I’d amassed in a rolled-up wad stuffed inside my Winston Churchill toby jug and about once a month Ed would drop around and we’d divvy up the spoils. He was a punctilious payer-out of royalty accounts; as good as his word in every respect. And my interactions with Ed as a publisher were much happier and infinitely more profitable than my experience with Applegarth. But by 1990, for reasons I’ve never really understood, our working relationship came to its end. It didn’t stop – bam. It just fizzled. I pitched him a couple of subsequent book proposals and found him unresponsive and even taciturn. As we’d never exactly ascended to the plateau of friendship, I didn’t feel I had any sort of right to demand a clearing of the air between us. I felt bad that I didn’t like him more than I did. But the difficult and prickly truth is that Ed Phelps could be a hard man to unreservedly like. Frequently in the grip of alcoholism and depression, he could be spectacularly coarse and vulgar and then turn all snarly at the drop of a hat. I was frankly nervous to be with him when we were around people I loved and cared about and who didn’t understand that, “Oh yeh, Ed can be like that.” It eventually became clear that not only did I no longer have his ear but he held me in a kind of contempt. About 1992 I was up at the Weldon Library doing some research in their files on the early history of the Baconian Club and as I was packing up to go, Ed slipped me a large photo-copied page, about the size of a restaurant placemat, saying, “Here, take this home for the kiddies.” Depicted on that page in cartoon format were about a dozen well-known Disney characters – Mickey Mouse, Snow White, Goofy and Clarabelle, etc. – engaging in a sexual orgy. I might have laughed it off as Ed being Ed if he hadn’t mentioned my kids. I didn’t throw a hissy fit on him or pull a Greta (“How dare you!”) but I didn’t laugh or smile either. I thanked him for his help, gave him back his scummy little page and left. But what you have to put up against all the tales of Ed being a misery-guts or an unconscionable pig are the stories of his generosity – which are legion. He helped dozens of area writers and historians and archivists, throwing them work and giving them crucial early breaks to get them started in their careers. Though I usually found the books Ed published (other than my own and one collection of charmingly erudite restaurant reviews by Andy MacFarlane) to be mind-crushingly dull, they did evince his unwavering devotion to the importance and value of the unvarnished historical record. He also offered a helping hand to historians in their dotage. Dan Brock once told me how Ed helped look after Elsie Jury in her failing years after the death of her husband, Wilfrid Jury. And in the last year of Orlo Miller’s life, when his income had dwindled to a trickle, Ed personally oversaw the re-issue of Miller’s most comprehensive city history, This Was London (originally published in 1988) as a tie-in with the city’s 1993 London 200 celebrations. This glitzy new edition, entitled London 200: An Illustrated History, featured larger page formatting to accommodate a wealth of great historical photographs which the earlier edition had lacked. And then the very next year, the scandal and collapse which Ed always seemed to be poised on the brink of, broke wide open with his arrest and conviction in the 1994 Project Guardian probe for the sexual exploitation of minors. There are a number of people I respect who may know more about these things than I do, who insist it was a put-up job. True or not, fair or not, it cost him everything – his career, his reputation – and, I expect, contributed to his decision on May 2nd of 2006 to end his life by walking in front of a Canadian National train. The last time I saw Ed, he came over to my house to pick up a letter he’d asked me to write that was going to be submitted to the person or the panel who would determine the duration of his prison sentence. I said every good thing about Ed that I could in that letter and I’m glad that I did because I owed him a debt of thanks and in the ordinary course of our relationship that was somehow very hard for me to express. Ed read it, we had ourselves a little cry, and then he walked off into his future which wasn’t about to get any better.

3 Comments

Leith Peterson

12/1/2021 09:57:19 am

Herman: I can relate to many of the anecdotes you mention in your post about Ed Phelps. However, I never had a writing connection with him. He knew my family and me, particularly my late father, going back to around the early 1970s.

Reply

Mark Richardson

12/1/2021 03:06:17 pm

Thanks for a good column, today, about Ed Phelps.

Reply

Roy Berger

3/1/2024 06:38:08 am

That was a very warm and decent piece, Herman. I had no idea how to write about him. Yeah, his archival stories and postal adventures were gut busting hilarious. Thanks for this.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed