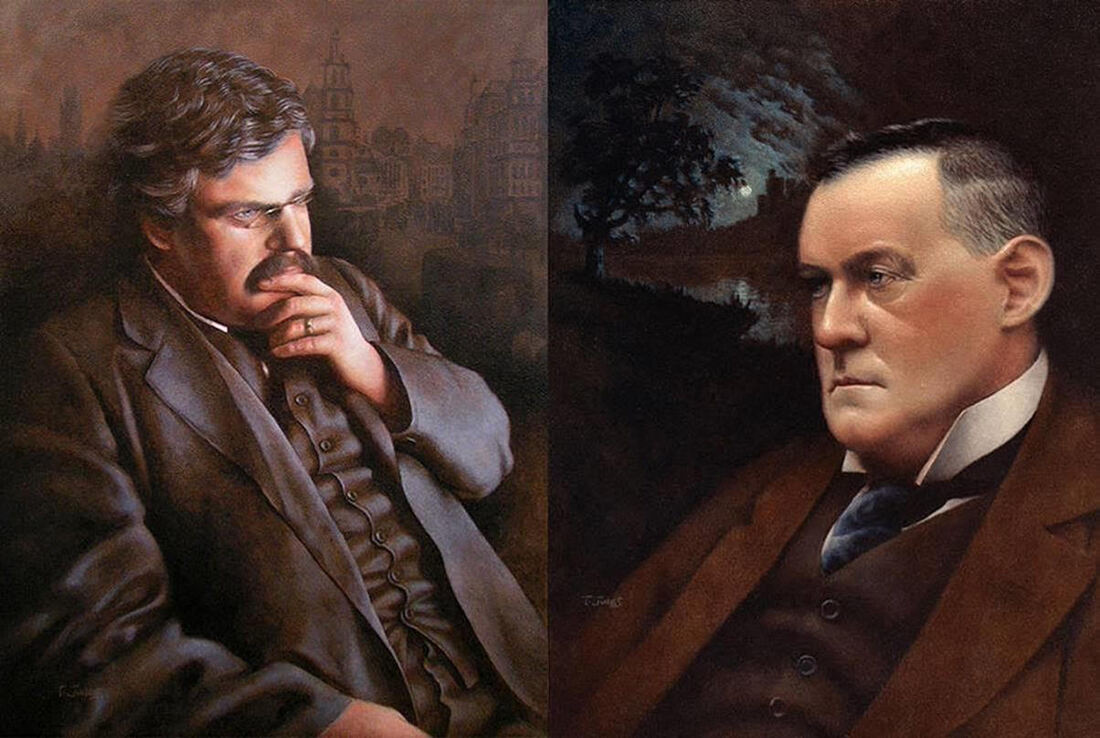

LONDON, ONTARIO – A few months back in a sprawling essay on the Brontes, I recalled my delight at visiting Britain’s National Portrait Gallery where I encountered dozens of full-sized portraits of beloved authors that I’d previously seen only as miniature, muddy, black and white frontispieces to classic editions of their works. No single painting in that gallery’s forty rooms was harder to tear myself away from that day than Conversation Piece (1932) by Herbert James Gunn (1893–1964). This wonderfully lifelike and almost life-sized portrait (it stands almost as tall as I do) depicts three giants of the Catholic literary revival of the 20th century gathered around a table at London’s Athenaeum Club in July of 1930: Maurice Baring, Hilaire Belloc and G.K. Chesterton. Some anonymous wag of the time re-dubbed this portrait – designating the subjects in the same order as I’ve outlined above – Baring, Overbearing and Past Bearing. The least well known of the trio, then and now, is the chap standing in back with a cigarette in his hand, Maurice Baring (1874–1945). Baring was born to a wealthy banking family and capitalizing on his remarkable facility for languages, served early on as a diplomat posted to Paris, Copenhagen and Rome. Tiring of the zipped up circumspection of the diplomatic life, he chucked that after a few years – and his superiors don’t seem to have been too heartbroken to see him go – to become a British press correspondent in Russia, amassing his widest readership with his dispatches from the Russo-Japanese war. Baring utterly immersed himself in Russian history and culture and always looked back on his years in Russia with great fondness. If there was a single writer who best represented his own literary ideal, then that would be Anton Chekov with whom he shared a subtly tuned eye for human nuance and a rare facility for dialogue. At the outset of World War I Baring returned to Britain and changing careers once again, rounded out his working years as a highly regarded staff officer with the Royal Air Force until Parkinson’s disease started to mess with his mobility and he gave himself over to his literary work for the final two decades of his life. Baring never married or had children and was able to spin off about forty books in his spare time. These included translations (mostly from Russian), various themed anthologies, history books and travelogues, collections of his own verse and some wildly eccentric essay collections; such as a satirical sampling of supposed diary entries of famous people and learned lectures on entirely imaginary historical events. Of his dozen or so wittily sophisticated novels (which are, in their way, more full-bodied creations than the fictions of Chesterton or Belloc) C, The Coat without Seam, Darby and Joan and Cat’s Cradle are the most frequently referenced today and his magically evocative childhood memoir, The Puppet Show of Memory, is generally regarded as his masterpiece.  Maurice Baring (1874–1945) Maurice Baring (1874–1945) A lifelong ornithologist whose gentlemanly demeanor camouflaged an impish sense of fun, Baring appears in a number of photographs with one of his budgies happily perched atop his hairless dome. It must have been a remarkably flat pate as (before his Parkinsonian tremors rendered the trick un-performable) he would sometimes set a full glass of wine up there if a table wasn’t close to hand. But when the occasion called for it – as when Belloc’s wife died at the age of forty-two or when Chesterton was fretting about his long-delayed conversion to the Catholic Church – there wasn’t a more solicitous or thoughtful friend than Maurice Baring. When Chesterton did finally summon the courage to make that leap of faith, his nerves were considerably steadied by Baring’s calming assertion in a letter that his own conversion was “the only action in my life which I am quite certain I never regretted.” I would have to read a lot more of his oeuvre before I could undertake a proper exploration of Maurice Baring. Today we’re really examining that pair of considerably more extroverted souls seated at that club table with him; two writers of much wider renown in their lifetimes who still have much larger readerships today. That is my main man, G.K. Chesterton (1874–1936) on the left and the famously bellicose Hilaire Belloc (1870-1953) on the right. And these are the two constituents who make up that mythical beast known as the ‘ChesterBelloc’. In Gunn’s group portrait, Belloc and Baring are looking on as Chesterton scribbles away in his notepad with a stubby pencil. Gunn worked up the first quick sketch for his painting at a gala party for Belloc’s 60th birthday. It is usually suggested that Chesterton is making notes of some kind and this might seem plausible enough in that he was one of the celebrants slated to speak in the birthday boy’s honour that night. But it would be most unlike the brilliant but shambolically exuberant Chesterton to fuss over-much about anything so jejune as a date or a proper sequencing of events or the spelling of a name. The obscuring curve of Chesterton’s hand makes it impossible to ascertain what he’s working on. But who would ever look on with such interest at mere words taking shape on another man’s page? I think it’s much likelier that Chesterton was whipping off one of his caricatures for another of Belloc’s satirical novels; fifteen of which were published (with as many as three dozen of Chesterton’s embellishments per volume) between 1904 and 1936. The Mercy of Allah (1922), a fable of financial chicanery was the most popular and has been reprinted many times. In Gunn’s portrait Chesterton could well have been working on pictures for The Man Who Made Gold which came out a few months after Belloc’s birthday or The Postmaster General which followed a couple years later. While Belloc may have been the better representational draughtsman of the two (his travelogues like The Path to Rome, Paris and The Four Men are replete with his own landscape sketches and maps) he did not have Chesterton’s genius for cartooning. Belloc repeatedly attested how essential Chesterton’s rapid-fire drawings were to the full conceptualization of his darkly comic tales. In a letter setting up one of their marathon drawing sessions – these typically took place at Chesterton’s home in Beaconsfield where they’d hunker down in Gilbert’s study for several intensive hours of smoking, laughing and drawing – Belloc writes: “I have already written a number of situations which you might care to sketch. I append a list. Your drawing makes all the difference to my thinking: I see the people in action more clearly . . . I can’t write ‘til I have the inspiration of your pencil.” In his wonderfully insightful panegyric for his friend, Monsignor Ronald Knox observed that, “The undercurrents of [Belloc’s] mind were sad, and his face never looked happy in repose.” And Belloc knew this about himself; particularly in the second half of his life, when he manfully struggled to remain productive and not succumb to the brooding disappointments and tragedies of his life; most particularly the too early deaths of his wife and the two sons he lost – one each – in the two World Wars. “The comedy in me is ailing,” he confessed in another late letter to Chesterton, setting up one of their cartooning sessions. When left entirely to his own comic devices – as in his surprisingly popular collections of verse about disagreeable children who meet bad ends called Cautionary Tales for Children and More Tales about Worse Children – Belloc wielded a mercilessly gruesome pen. While short poems about "Jim, who ran away from his nurse, and was eaten by a lion" or "Matilda, who told lies and was burned to death" might go down well enough in miniature installments (and would be lightened a little by the inherent delight of the rhyming form itself) it would be a chore to slog through any of his 250-page satires – no matter how wacked-out the story might be – without those airy Chestertonian cartoons to jolly things along. While these illustrated satires came to be known and advertised as ‘ChesterBellocs’ – and to this day, you can find first editions of these concoctions listed as such in booksellers’ catalogues – the original coinage of that cumbersome term was the work of George Bernard Shaw in a 1908 debate. From the turn of the century through to the 1930s, dozens of authors with the requisite temperament and a knack for tossing off pertinent information under pressure, enjoyed profitable sidelines by taking part in these well-attended contests of eloquence and persuasion. Writers who are almost entirely forgotten today like G.G. Coulton, J.B.S. Haldane, C.E.M. Joad and Arnold Lunn could pack out university lecture halls and public theatres, both at home and abroad, for their verbal bouts of parry and thrust. The four giant controversialists of this golden age – all of them names that do still reverberate today – were Shaw, H.G. Wells, Chesterton and Belloc. These gents wouldn’t just assail each other at the podium - Shaw and Chesterton, for the most part, good-naturedly; the other two with considerable vituperation – but would also carry on and amplify those debates in the popular press. The thinner-skinned Wells and the ever-scrappy Belloc really seemed to get up each other’s noses and would gather up their ‘broadsides’ into scarcely edited books like Belloc’s highly critical Companion to Mr. Wells’ Outline of History, countered by Wells’ Mr. Belloc Objects, which was then refuted by Mr. Belloc Still Objects. As usual Belloc had the last word and by general consensus is regarded as the winner of that dispute. But it must be admitted that their more than century-old pissing match (while profitable in its day) doesn’t make for terribly compelling reading today. Maurice Baring instantly recognized Shaw’s coinage as a shabby disparagement that sold both writers short and he lamented the speed with which the lumpen slur attained popular currency. Yes, Belloc and Chesterton shared a faith which powerfully shaped their views of the world but that hardly made them identical as thinkers or writers. Though they both wrote with uncommon verve and insight, their talents were uniquely honed and expressed. Baring felt a real injustice was committed – that due credit would be withheld from both – when his distinctively brilliant friends were mashed together as some sort of grotesque literary tag-team. My real preoccupation in this essay is to wrest these two geniuses from the obscuring and confining pantomime costume of the ChesterBelloc so as to let each one of them stand forth as his own man. As I’ve written about Chesterton extensively (some might say ad nauseam) elsewhere, I’ll be focusing here much more on Belloc. For my single deepest Chestertonian dive, I invite you to dig into my 2019 Aquinas Lecture which can be accessed at this link: https://www.hermangoodden.ca/blog/the-aquinas-lecture-on-gk-chesterton And I also offer that lecture as evidence that it is possible to appraise Chesterton’s life and accomplishments in considerable detail without so much as mentioning Hilaire Belloc once. And again, I do not point this out for the purpose of denigrating Belloc – I will be celebrating his greatness here – but to discourage the tendency to regard either half of the ChesterBelloc as the real leader and the other as the follower, or, less politely, to designate one as the head of the beast and the other as the buttocks. Hilaire Belloc was born in France to mixed French and English parentage and following the death of his father when the boy was two, he was primarily raised in England; living with his mother and sister in Sussex and frequently staying with maternal relations on Wimpole Street in London. Notably forthright and confident even as a child, Belloc’s peripatetic childhood – regularly slipping across the channel to stay with paternal relations in St. Cloud and Paris – imbued him early on with a sense of European and British culture and history and outfitted him for what would turn out to be a life of near-constant travel and geographic exploration. A prodigious hiker as a young man, the first work of prose that won Belloc broad popular success was his alternately rollicking and thoughtful account of a solitary tour he undertook on foot from France to the Eternal City, The Path to Rome (1902). The narrative frame of a later, less exuberant but more meditative volume of autobiographical reflections, Cruise of the Nona (1925), is provided by a journey he helmed as a middle-aged widower in his own small boat from southern English coastal towns across the channel to Dunkirk and the capes and inlets of northern France. The only writer I know who can rival Belloc’s uncanny evocation of landscapes - bringing fascination and even excitement to what in lesser hands are supplementary passages - is the American novelist, Willa Cather. The single greatest hike he ever undertook was as a cash-strapped twenty year-old when Belloc walked half way across the American continent to propose to the woman who would eventually become his wife; earning money for meals and lodging along the way by gambling at cards, giving poetry recitals and selling his sepia landscape sketches. Of course he gathered details and impressions en route, all of which came in handy for a later book comparing the old world and the new, The Contrast. But most of all he was in besotted pursuit of nineteen year-old Elodie Hogan who he’d first met in the fall of 1890 when she and her mother and a sister wrapped up their grand tour of Europe with a couple of months’ stay in London. And when Mrs. Hogan was called back home one month ahead of schedule to attend to urgent family business, the couple was never left unchaperoned exactly, but Belloc saw Elodie every day and became her prime tour guide. Belloc certainly would’ve popped the question earlier if he hadn’t understood that Elodie’s plan was to enter a convent when she got back to California. But the flurry of letters that flew between them as soon as Elodie left Britain, seemed to reveal a slackening of her resolve to seal herself away in a nunnery, and Belloc wiped out his savings to book his trans-Atlantic passage to go chasing after her in early January of 1891. While Mrs. Hogan was at least as pious as her daughter and thought the religious life would suit Elodie well, she probably would’ve been more amenable to the idea of marriage if Belloc’s prospects had been more promising. And both of our principals’ widowed mothers vigorously discouraged the match, deeming their children too young to even be contemplating marriage. Belloc, of course, was headstrong enough to disregard any maternal qualms. But the more biddable Elodie wasn’t constituted that way and did still want to see if her vocational call was genuine, though she took her sweet time in putting it to the test. And so, with much anguish all round, Elodie rejected her transatlantic suitor and a shattered, penniless Belloc returned to Britain alone. The couple did resume their correspondence but in a more desultory and less frenzied way as Elodie began attending to her mother whose health went into a sharp decline which soon carried her off. Always good at nullifying misery through work, Belloc soon signed on for a sorrow-smothering, one-year term of military service with a French artillery regiment near Toul. And he followed that up with an outstanding four-year career as a history scholar at Balliol College, Oxford where he earned first-class honours and so distinguished himself as a formidable debater that he was made President of the Oxford Union. Belloc took it hard when his student success couldn't be parlayed into an opportunity to set foot on even the lowest menial rung of the professoriat. That shop was utterly closed to him; implanting a grudge against academic xenophobia and narrow-mindedness that he bitterly nursed for the rest of his life. In 1895 Elodie had finally worked up the courage to enter the convent and then bailed out after living for only one month as a postulant. Whereas Belloc was just starting to make his way in the world as a writer and a journalist, Elodie was now at loose ends and a bit of a wreck. When he heard of the fragile state she was in, Belloc dropped everything to race back to the States (this time with his mother in tow) to plight his troth one more time and bring Elodie back with him to wed. Greatly assisted by the ministrations of Belloc’s mother and sister, Marie (who became a writer of considerable popularity herself; her novel, The Lodger, was adapted for the screen and directed by a very young Alfred Hitchcock) Elodie recovered from her nervous exhaustion and she and Belloc set up their first home and began populating it with their eventual brood of five rambunctious children. Saddled with the welcome responsibility of providing for all these dependents, Belloc doubled his drive and narrowed his focus to really get his literary career underway; inspired, he once joked, by the need to keep his children plied with caviar. Though Belloc was only forty-three when Elodie died of cancer in 1914, he was not the sort of man who could even contemplate the idea of marrying again. He wore black broadcloth for the rest of his life, always wrote personal letters on stationery that was edged in black and before turning in each night (when he was at home and not away on some writing assignment) would make the sign of the cross on the doorway to Elodie’s room. Let me set down here a representative paragraph of Bellocian prose at its best. One of his most frequently anthologized essays is The Mowing of a Field from perhaps his single most celebrated essay collection, Hills and the Sea (1906). Small wonder. Just look at the apparent ease of his writing style here, the plethora of practical knowledge that he is able to draw on and the utterly natural authority with which he casts his narrative net: ”So great an art can only be learned by continual practice; but this much is worth writing down, that, as in all good work, to know the thing with which you work is the core of the affair. Good verse is best written on good paper with an easy pen, not with a lump of coal on a whitewashed wall. The pen thinks for you; and so does the scythe mow for you if you treat it honourably and in a manner that makes it recognize its service. The manner is this. You must regard the scythe as a pendulum that swings, not as a knife that cuts. A good mower puts no more strength into his stroke than into his lifting. Again, stand up to your work. The bad mower, eager and full of pain, leans forward and tries to force the scythe through the grass. The good mower, serene and able, stands as nearly straight as the shape of the scythe will let him, and follows up every stroke closely, moving his left foot forward. Then also let every stroke get well away. Mowing is a thing of ample gestures, like drawing a cartoon. Then, again, get yourself into a mechanical and repetitive mood: be thinking of anything at all but your mowing, and be anxious only when there seems some interruption to the monotony of the sound. In this, mowing should be like one’s prayers – all of a sort and always the same, and so made that you can establish a monotony and work them, as it were, with half your mind; that happier half, the half that does not bother.” The most insightful study of Belloc’s work that I know is an obscure little text that is quite hard to find, written by a young Frederick Wilhelmsen in the year of his subject’s death, Hilaire Belloc: No Alienated Man (1953). That subtitle might strike you as a tad eccentric but Wilhelmsen wrote at a time when, following a mentally discombobulating stroke, an exhausted Belloc hadn’t picked up his pen in more than a decade and was in the process of being forgotten. An entirely different sort of literature than Belloc’s held centre-stage now and whether it was played for laughs or defeatist melodrama, the big preoccupations of the day were irony, alienation and existentialist angst. In his concluding pages, Wilhelmsen asks: “Why is it that Belloc’s reputation has suffered so severely within the last fifteen years? Part of the neglect is probably due to the fate of his own generation. The whole Edwardian and Georgian period is engulfed under the snobbery of the avant-garde. The heartiness, the zest for existence, the enormous interest in almost everything, the sheer magnificence of the Edwardians seem pretentious and a trifle adolescent to a youth who has aged young in an old world now dead. A change in fashion partially accounts for Belloc’s decline in popularity, but there is something deeper than mere fashion. If Belloc is not understood today, it may be because his own brand of Christian integration has become almost impossible of achievement at this late date in the disintegration of the Western World. Most of us are not rooted men; we do not live in a traditional culture, and to pretend to do so would be to fall into an archaic lie. The Christian living in the centre of an industrialized secularism is without sustenance . . . Man is no longer at home." One notable manifestation of the ‘integration’ and ‘rootedness’ that Wilhelmsen admired, was Belloc's apparent incapacity to feel intimidated. Admonitions against giving offense went utterly unheeded and so far as I know, he was never once coerced into asserting something he didn’t believe. Whether obfuscating hooey was emanating from some high office or just a poor lost soul with a need to believe a comforting lie, Belloc would pugnaciously or mockingly attack; as the situation required. Rarely known to sacrifice a point with grace - and certainly not without putting up a good fight first - Belloc’s whole rhetorical approach was unapologetically masculine. A very telling review of his satirical novel, Emmanuel Burden, in Vanity Fair sniffily claimed that, “Not one woman in a hundred will extract a laugh from its pages.” (Gosh, I think I actually know that nearly non-existent woman.) The charge of racism, most specifically anti-Semitism, is often laid at Belloc’s feet. I believe the charge is answered most ably by J.B. Morton in the memoir he wrote after his friend’s death. “A celebrity has always to be prepared to be misrepresented and misquoted, and Belloc had his share of this. Somebody starts an anecdote on its travels, it is repeated, finds its way into print, and the mischief is done. No amount of subsequent contradiction can kill the story. It is finally entrenched. Many times I have heard people quote “How odd of God to choose the Jews,” and attribute it to Belloc. Once this happened in his presence, and he said, “That’s not the way I write.” But people continue to attribute it to him, probably because of the false idea that he was what is called “anti-Semitic.” He liked or disliked a Jew as he liked or disliked any other man, and he wrote a book called The Jews, which those who called him an “anti-Semite” should have taken the trouble to read.” To this I would only add that I have never conversed with a Jew who took any sort of offense at Belloc’s heavy-handedness in this regard. The complaint only seems to get tossed about by atheists, agnostics and miscellaneous lefties who’ve read precious little Belloc (or Chesterton for that matter) and otherwise manifest no particular regard for the good name or well-being of the Chosen People. Two other affectionate memoirs of Belloc that were published shortly after his death (when massive sales were not likely to ensue) were written by his sister, Marie Belloc-Lowndes, and his daughter, Eleanor Jebb. In my experience, hate-filled monsters do not inspire such acts of devotion from the people who knew them best. With a fond shake of her head, Jebb writes of Belloc’s proclivity for speaking his mind: “I have seldom met anybody who could be so unselfconscious as my father when he was talking to his friends. I have often seen scowling colonels in hotels and restaurants leave the room in twitching rage because of the disturbance he could cause with the mere fun of life or a drink with a friend.” From 1906 to 1910 Belloc served a single, disillusioning term as a Liberal Member of Parliament for the riding of Salford South and then quit politics for good (though his parliamentary experience supplied some insights which he put to use in his satirical novels). During the campaign the Conservative incumbent tried to play on popular prejudice with the slogan, “Don’t vote for a Frenchman and a Catholic." Belloc was counseled by party strategists to not rise to the bait and simply brush it off. Instead, he opened the very next debate with, “Gentlemen, I am a Catholic. As far as possible, I go to Mass every day. This [pulling some beads out of his pocket] is a rosary. As far as possible, I kneel down and tell these beads every day. If you reject me on account of my religion, I shall thank God that He has spared me the indignity of being your representative.” And when a heckler sought to embarrass him on his half-French parentage by calling out “Who won Waterloo?” – probably, Chesterton conjectured, the only battle the heckler had ever heard of – Belloc shot back with: “The issue of Waterloo was ultimately determined, chiefly by Colborne’s maneuver in the centre, supported by the effects of Van der Smitzen’s battery earlier in the engagement. The Prussian failure in synchrony was not sufficiently extensive however and . . . “ Concluding her account of her father’s brief political career, Eleanor Jebb wrote, “For one who knew the world, he had a curious belief in his fellow men, and this was profoundly shaken by what he found going on among politicians. He had not known how fixed the system was, with its generations of privileges . . . As yet, he was no angel himself, but he found it impossible to conform to the almost club-like atmosphere of never challenging certain glaring dishonesties.” Together with her husband Frank Sheed, Maisie Ward served as a publisher for Chesterton and Belloc and came to know both of them very well. She outlines the fundamental differences of their natures in a fascinating passage from her autobiography, Unfinished Business. “There is, I fancy, no historian who, as fully as Belloc, has mastered geography as ‘the eye of history’. . . . In The Ballad of the White Horse, Chesterton has the right wing of one army facing the right wing of the other. His sense of time and place, his descriptions of the things around him with their violent colours and intensities, are elements in a vision, not something another man could see ... With people, however, the role of these two men is reversed – here Belloc sees with the imagination while Chesterton looks at what is – even should he sometimes magnify men’s splendid virtues.”

Ward then goes on to tellingly contrast how each man wrote about their separate experiences of staying with friends in the country over a long weekend: “Both of them, staying in country houses, had their pockets turned out, their clothes brushed, by a footman. Chesterton gives a line or two to the topic and smiles as he describes the sordid contents of his own pockets and contrasts them with the ‘jewelled trifles’ that might have been found in the pockets of the rich. For Chesterton the experience was highly diverting. For Belloc it was humiliating. He wrote a whole essay on The Servants of the Rich, whose pleasure it was ‘to forget every human bond and to cast down the nobler things in man: treating the artist as dirt and the poet as a clown’; and he depicts as writhing in the flames of Hell ‘the men who in their mortal life opened the doors of the great Houses and drove the carriages and sneered at the unhappy guests’. I may be told that this essay is sheer irony – but there is too much emotion here for irony.” Another key difference between the two was how they came by their faith. Unlike Chesterton the nervous convert, Belloc was a cradle Catholic, steeped in the faith from birth. As a boy he rubbed shoulders with Gerard Manley Hopkins and St. John Henry Newman and actually came to know Cardinal Manning fairly well. In the final analysis, Belloc may have written about the faith as much as Chesterton, but he did so in a very different way; not as way of life that a rational man might choose for himself but an elemental fact of human existence; not so much as a divine blessing that could save one’s sanity and soul but as the great organizing principle that shaped all human culture and civilization. In his great panegyric delivered at Belloc’s requiem mass at Westminster Cathedral, Monsignor Ronald Knox contrasts the two men’s gifts as Catholic commentators like this: “To be sure, [Belloc] was prophet rather than apostle; he did not, as we say, ‘make converts’. You do not often hear it said of Belloc, as you hear it said of Chesterton, ‘I owe my conversion to him.’ But the influence of a prophet is not to be measured on a single mind here and there; it exercises a kind of hydraulic pressure on the thought of his age.” Maisie Ward’s husband, Frank Sheed, took Knox's assertion even further. “More than any other man,” Sheed wrote, “Belloc made the English-speaking Catholic world in which all of us live.” Those are very extravagant claims but with a little historic context, one can see what both Sheed and Knox were getting at. In numerous books like How the Reformation Happened, The Great Heresies, Characters of the Reformation, Europe and the Faith, The Catholic Church and History and his biographies of Charles the First, Cromwell, Wolsey, James the Third, Cranmer, Becket and Joan of Arc, Belloc peeled back the predominantly and self-servingly Protestant interpretation of British and (to a lesser extent) European history to reveal the richness and beauty of all that had been swept aside and stolen in the first upheavals and long wake of the Reformation. Though the persecution of a once proud church had eased significantly over the previous couple centuries – which is to say the civil authorities had stopped murdering priests, destroying monasteries and swiping great cathedrals to repurpose as Anglican temples – subtler forms of oppression remained. And it did early twentieth century Catholics a world of good - you could say it hydraulically lifted their spirits and their view of their forbears and themselves - to read Belloc’s revelatory chronicling of what had actually gone down. In his introduction to an anthology of essays by various hands, Hilaire Belloc: The Man and his Work, Chesterton recalled his first meeting with Belloc in 1900 when he was twenty-six and Belloc was thirty. “When I first met Belloc, he remarked to the friend who introduced us that he was in low spirits. His low spirits were and are much more uproarious and enlivening than anybody else’s high spirits. He talked into the night, and left behind in it a glowing track of good things . . . What he brought into our dream was his Roman appetite for reality and for reason in action, and when he came to the door there entered with him the smell of danger.” Because Belloc lived twenty-one years longer than Chesterton and the world got to know him as an old man, the instinctive impression in most people’s heads is that the gap between their ages must’ve been twice or three times as large. “Four years isn’t all that much,” you might be thinking. But it can be at that age, particularly when the backgrounds, experiences, temperaments and imaginations of the two men are so very different. Consider that on that evening when they met, Belloc was a married man with a third child on the way and Chesterton was still affianced and living at home with his parents. Belloc had walked across large swaths of Europe and America and served for a year in the French artillery while Chesterton was known to wire home for directions when he lost track of time and knew he was due to be somewhere else but couldn’t remember where. Belloc, clearly, was a take-charge kind of guy; just the fellow you'd want at your side if you were planning a trip or taking down a large tree. And because Chesterton lived so completely in his head and struggled to meet the more mundane and practical challenges of daily existence, he is the one who is most often depicted as the follower or pupil in the ChesterBelloc equation. But when it came to the writing, what he put down on the page, this just wasn't so. Before the two halves of our mythical beast met, Chesterton already had his own unique voice and perspective and he already had his Christian faith which was at least seventy-two percent Catholic even before he officially converted a couple decades later. But until Belloc came trailing danger into their dreamlike meeting that night, Chesterton hadn’t yet summoned the nerve to toss off certain instinct-muffling conventions so as to stand forth as a man of letters with all of his brilliant peculiarities intact. Yes, Belloc was an exemplar to the younger writer. but not as a stylist and not, strictly speaking, in terms of the subject matter he took on; which is to say Chesterton did begin to turn up the religious content in his writing after their meeting .What so impressed Chesterton that night was to come face to face with an artist who wasn't afraid to bring everything he had into the game whether editors or even the reading public regarded it as quite appropriate or not. But the manner in which Chesterton did this, was completely different from Belloc's. It simply wasn’t in Chesterton’s nature to ever be as in-your-face combative as Belloc. (And off the page, one benefit of this was that the friends Chesterton made, remained so for life.) But Chesterton’s insights - not one iota less forceful even though they frequently emerged from his irrepressible sense of playfulness - could be as arrestingly sharp as cut diamonds.. How telling is it that they both wrote two books about saints and Belloc's (Joan of Arc and Thomas Becket) were defiant warriors brought down in violence and Chesterton's (Francis of Assisi and Thomas Aquinas) confined their world-transforming battles to the arenas of the spirit and the intellect. Belloc passed his final decade in comparative obscurity and silence, growing a great woolly beard and padding about the sprawling and now rickety Sussex farmhouse called King's Land that he never really could quite afford but lived in for nearly all of his adult life. Though the fields around the house were now rented out and worked by neighboring farmers, Belloc loved to think of himself as a landowner and wouldn’t consider doing the sensible thing of moving to some smaller and more manageable place that didn’t enshrine the memory of his beloved Elodie and that time when their home was teeming with kids; that didn’t have a small private chapel where friends like Monsignor Knox might drop by to say Mass; that didn’t have all these French doors leading directly out onto the lawn where he liked to slip out on a temperate night and pee while gazing up at the stars. He was discreetly watched over now by his daughter, Eleanor, who lived with her family in their own wing of the house and was regularly visited by friends who knew how to steer conversations so as to limit the repetition of topics. He took a lot of naps in a fireside chair where a mouse would sometimes wake him up while rooting around in his housecoat pocket where he’d squirreled away bits of cheese and bread. And there was a lot of repetition in his reading as well. He particularly enjoyed the novels of P.G. Wodehouse and C.S. Forester and regularly revisited favourite books of his own – and his taste in these was spot on – like The Path to Rome, The Four Men, Belinda, and his poems, several of which he’d set to tunes of his own devising and could be heard singing a-cappella late into the night. Some people find the circumstances of Belloc’s dotage pathetic. I actually find it all kind of comforting. But let me leave you with a different final snapshot that was taken by Chesterton in the prime of Belloc’s life. It has been eight years since the ChesterBelloc first met. A now married Chesterton is doing well enough that he can afford to rent a house for the summer in Rye which is right next door to the rather tony abode where expatriate American novelist Henry James has similarly taken up residence. Mindful of etiquette and decorum and how things ought to be done in the old world, James waits a few prudent days before coming over to take tea with Chesterton and Frances in their back garden. And that is when and that is where, much to Chesterton’s surprise and delight, Belloc, unannounced and literally climbing over the wall, drops in with his hiking companion from a Continental walking tour that has not gone well. As Chesterton writes in his autobiography: “Their clothes collapsed and they managed to get into some workmen’s slops. They had no razors and could not afford a shave. They must have saved their last penny to re-cross the sea. And then they started walking from Dover to Rye where they knew their nearest friend for the moment resided. They arrived, roaring for food and drink and derisively accusing each other of having secretly washed, in violation of an implied contract between tramps. In this fashion they burst in upon the balanced teacup and tentative sentence of Henry James. “Henry James had a name for being subtle but I think that situation was too subtle for him. I doubt to this day whether he, of all men, did not miss the irony of the best comedy to which he ever played a part. He left America because he loved Europe, and all that was meant by England or France; the gentry, the gallantry, the tradition of lineage and locality, the life that had been lived beneath old portraits in oak-paneled rooms. And there, on the other side of the tea-table, was Europe, was the old thing that made France and England, the posterity of the English squires and the French soldiers, rugged, unshaven, shouting for beer, shameless above all shades of poverty and wealth; sprawling, indifferent, secure. And what looked across at it was still the Puritan refinement of Boston, and the space it looked across was wider than the Atlantic.”

1 Comment

Max Lucchesi

27/1/2023 08:47:56 am

As usual Herman, informative and well written, also as usual not the whole truth about Belloc. From his paternal relations he acquired the French upper class' virulent anti semitism. He usually referred to Jews by the 3 letter word beginning with Y. Was an active anti Dreyfusard, so much so that 40 years after it was all over and Dreyfus' innocence was proved beyond doubt, he could still say. "Poor darling, he was as guilty as sin". Allan Messie's article in the Catholic Herald, Belloc and Anti Semitism, apologised for him by putting him within the context of the time. A.N. Wilson in his biography of Belloc, actually glossed over and drew attention to Hitler's anti semitism. That's O.K then, Belloc wasn't as anti semitic as Hitler. Apart from his poetry, the only book of his I've read is his 'How the Reformation Happened' which even for a Catholic is seriously biased. I hope that on his road to Rome he walked there along the Via Francigena, he had much to be forgiven for. You know my view of G.K.C.; of Baring only that the family bank went bust in 1995 because of Nick Lreson and £827 million in fraudulent investments. 'Baring. Over Baring and Past Bearing' just about sums it up.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed