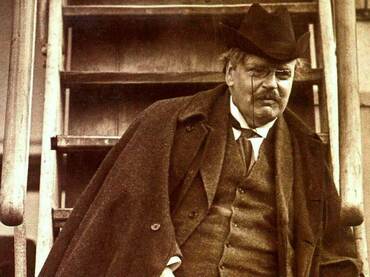

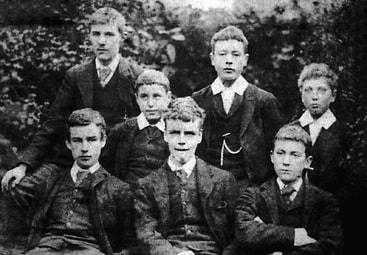

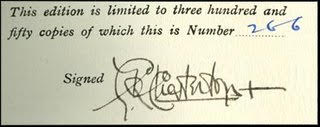

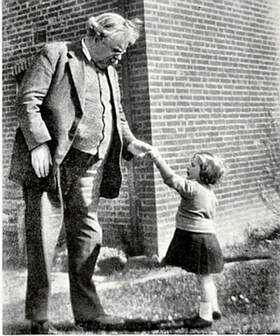

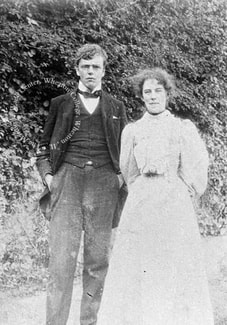

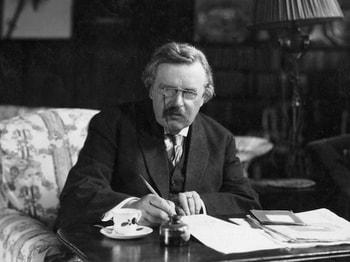

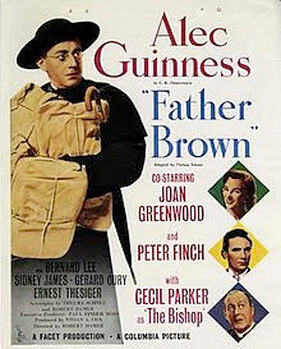

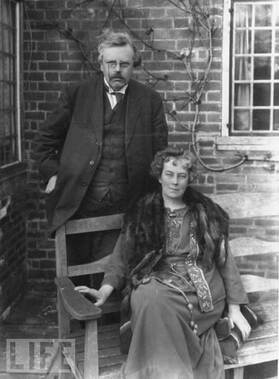

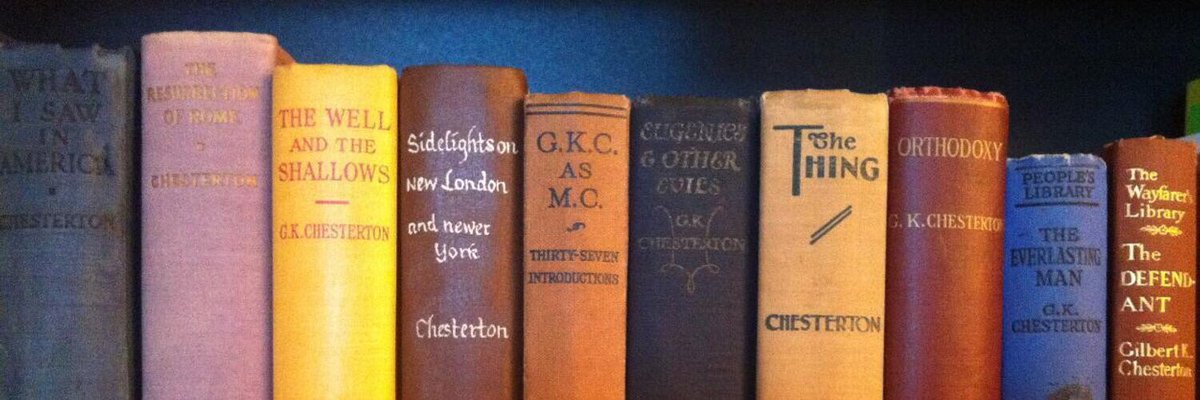

G.K. Chesterton: The Big Picture G.K. Chesterton: The Big Picture LONDON, ONTARIO – I first became aware of G.K. Chesterton (1874–1936) in my late 20s on a literary tip from my friend Jeff Cencich. “I think you’ll like this guy,” he said, plucking a copy of his Selected Essays from a shelf at City Lights Book Shop where I was working as a clerk and dropping it onto the counter. Oh, gross and magnificent understatement. Over the course of my reading life I’ve known dozens of instances when I’ve first knocked back a certain writer’s book that goes down with such avid delight that I hate myself for not being able to slow down to make it last. And as the final page of that first book hoves into view, I nervously start to ponder whether this writer has written much else and what are the odds that anything else in their canon will be a fraction so good as this? It’s an addictive sort of predicament, for sure, but if you’re going to get hooked on any writer, I would recommend Mr. Gilbert Keith Chesterton as the perfect gateway stimulant. He is such a prodigiously generous supplier of words that there will be no need to face the dreadful prospect of going cold turkey for many years to come. As I identified with Chesterton so immediately and so strongly, I’m glad the introduction wasn’t made any sooner; that my character and literary proclivities were more or less established before he arrived on my scene. We’re both inclined to portliness. We both have walrus moustaches. We share a birthday. (I do not harbour pagan superstitions but I must admit the sky cracked open and I was suddenly bathed in a cone of celestial light when I discovered that coincidence.) And we both enjoy the composition of humorous essays. The overlap between us (cue Twilight Zone music) was a little spooky. I admire the man tremendously but I’d hate to be accused of aping him. Of course, the date of my birth was my parents’ idea (though I’m not sure they sat down with a calendar for 1952, circled the 29th of May and said, ‘Let’s shoot for that one’). The moustache, rotundity and writing, I came up with on my own. Yet even arriving as late in my life as he did, the scope for influence was still there. When he hasn’t formed, he’s at least firmed up a number of my convictions about journalism and literature, society and the family, and he played no small part in calling my bluff on my perpetually postponed showdown with Christianity; dragging me, not quite kicking and screaming, into the Roman Catholic fold. There are dozens of writers I admire but Chesterton and Dr. Samuel Johnson (1709-84) are heroes. Dr. Johnson, I might mention, shares a birthday with my brother Ted. (What were my parents trying to get at?) Both these men were the subjects of sprawling, multi-volume, very frank and very indulgent biographies written shortly after their deaths by people who’d known them well – James Boswell’s 1200 pager for Johnson, and Maisie Ward’s more modest 920 pages for Chesterton. As a near contemporary and friend as well as his publisher – with her husband, Frank Sheed, Maisie ran the dynamic Catholic publishing house of Sheed & Ward – she knew Chesterton the man in a way that no subsequent biographer ever will. In spite of all their reported weaknesses and fears, contradictions and warts, the portraits that emerge are riveting in their originality, wisdom, kindness and goodness. Both men came with so many different parts yet both were so completely ‘of a piece’; were such unshakably consistent exemplars of their own true selves in every time and circumstance. They didn’t have to become meek dopes in order to become Christians. Their faith didn’t rest upon powder kegs of doubt or uncertainty that were too dangerous to examine. They didn’t stand in judgement of others of differing views but instead engaged and wrestled with them whenever possible and had enormous fun in the process. While Johnson’s readiness to suffer fools gladly probably wasn’t as pronounced as Chesterton’s, the sheer conviviality of these physically substantial and quintessentially English gents would make them ideal models for Toby jugs. IN MY TALK THIS EVENING I hope to sketch out a broad outline of Chesterton’s life and career with a particular emphasis on the key years of his intellectual and spiritual formation. I will also give you some sense of the staggering range of his literary output while pointing out those works which I believe to be the most significant. I warn you up front that if I should seem to be jumping around a bit . . . chronologically or thematically . . . well, that’s not exactly an accident. The proper treatment of a man as unorthodoxly orthodox as Chesterton kind of demands it. What will be consistently woven right through this talk, however, is the engagingly provocative and stimulating voice of Chesterton, himself. And many of the quotes I’ll be sharing with you – perhaps even a slight majority – will be expressions of one or the other of what I consider to be the big overarching ideas of the Chestertonian philosophy. And these are: 1) Your ancestors probably weren’t all that stupid or wicked; there’s a lot to be said for tradition. And 2) Life is a gift. Every gift has a giver. That giver deserves thanks. Today, 83 years after his death, new collections of Chesterton’s work are still being unearthed and published. Of course stray essays and poems are suddenly discovered and whenever enough of these accumulate, they are herded between covers. But even a lost novel made its debut as recently as 2001. Basil Howe, a metaphysical romance composed in his 19th year, was assembled from a cache of notebooks that unexpectedly turned up in the bottom of a trunk of non-literary paraphernalia following the death of Chesterton’s last secretary, Dorothy Collins. More than a hundred books were published in his lifetime and if a final tally ever is reached, the total number of works published under the name of Gilbert Keith Chesterton will certainly add up to more than 200 separate volumes. Usually the only writers who compile such staggering monuments to literary industry (‘Come on down, Barbara Cartland’) are the worst kind of hacks or are good enough writers who establish a narrow turf which they can easily work over and over again. What astonishes one in appraising the work of Chesterton is the number of different literary categories in which he excelled. Indeed, he seems to have expended his gifts so lavishly and diffusely that the academic curators of literary reputation have simply never known what to make of him. One of the most frequently quoted authors in the English-speaking world, he is much more known of, than known. He is much more cited for his aphoristic shards that illuminate some particular point, than acknowledged for the totality of his thought. And quite maddeningly, one of the quotes most frequently attributed to him – “When a man stops believing in God, he doesn’t then believe in nothing; he believes in anything” – isn’t his. It could have been. It pretty well has the right swing. But it just isn’t. So here’s one from his book, Heretics, that marks out the same sort of territory: “Take away the supernatural, and what remains is the unnatural.” In addition to writing too much about everything, Chesterton further confounded the expectations of sober-minded readers by committing the literary equivalent of refusing to colour inside the prescribed lines. Maisie Ward observed that, “A man starting to write a thesis on Chesterton’s sociology once complained bitterly that hardly any of his books were indexed, so he had to submit to the disgusting necessity of reading them all through, for some striking view on sociology might well be embedded in a volume of art criticism or be the very centre of a fantastic romance.” Ward maintained that this refusal to write about one thing at a time and keep his subjects and themes inside their own air-tight containers, wasn’t a mark of sloppiness or negligence, but rather was a reflection of what many of us find so uniquely compelling about Chesterton as a writer; that his “was a philosophy both universal and unified”. Early on in my search for anything else he’d written, I happened upon one of his harder-to-find titles, his 1904 critical monograph on the Victorian allegorical painter. G.F. Watts. All that I knew Watts for was his single most famous painting; a dank and grim image of a blindfolded woman sitting on top of a globe in a posture of despair as she plucks at the last remaining string on a broken lyre to which she is chained. I don’t think I even knew that Watts called this painting, Hope. I’ve belonged to a Christian men’s reading club that has been meeting once a month for the last quarter century. And a theme that comes up like a startling bulletin at every other one of our meetings is, “Oh man, has the Church ever been more abysmally threatened than it is today?” Granted, the shameful events of the last year have at least provided a little novelty for us in shifting the sharpest points of that threat from outside the walls of the Church to inside. But whenever our group really gets flapping about in its headless-baptised-chickens-of-the-apocalypse mode, I am tempted to read them this paragraph in which Chesterton describes the growing sense of meaning that dawns on a hypothetical viewer as he stares into the murky depths of Watts’ most famous painting:  G.F. Watts: Hope G.F. Watts: Hope He sees “something for which there is neither speech nor language, which has been too vast for any eye to see and too secret for any religion to utter, even as an esoteric doctrine. Standing before that picture, he finds himself in the presence of a great truth. He perceives that there is something in man which is always apparently on the eve of disappearing, but never disappears, an assurance which is always apparently saying farewell and yet illimitably lingers, a string which is always stretched to snapping and yet never snaps. He perceives that the queerest and most delicate thing in us, the most fragile, the most fantastic, is in truth the backbone and indestructible. He knows a great moral fact; that there never was an age of assurance, that there never was an age of faith. Faith is always at a disadvantage; it is a perpetually defeated thing which survives all its conquerors.” This brilliant formulation of the inextinguishable dynamic of that religion which is founded on a Man who overcame public execution on a cross, is not to be found in any of Chesterton’s celebrated works of apologetics but incidentally turns up in one of his least known books in which he pays tribute to a largely forgotten artist. Another complaint that our intellectual superiors lob at Chesterton (when they pay him any mind at all) is that his intuitive, exuberant and paradox-packed prose lacks intellectual grounding and rigour. In other words, his manner of thinking is altogether too mercurial and he’s way too funny. I get it. If you’re in the business of baffling and intimidating people, of putting their critical faculties to sleep so you can pound any sort of insane nonsense into their heads – such as the discovery that human beings have been mistaken for untold millennia in their assumption that there are only two sexes (and that one of those sexes has always been toxic anyway) – then you will not tolerate writing of any sort that threatens to wake readers up. In one of his very first published essays that brought him broad public notice, Chesterton expressed his uneasiness with Britain’s waging of the Boer War, sensing that this push-back against colonial independence had more to do with protecting certain Britons’ financial interests, than any vital or valid interest of Britain as a whole. When political leaders and editorial writers tried to suppress a rising tide of doubt by declaring this skirmish to be an unassailable matter of patriotic principle, Chesterton lampooned their shameless jingoism by means of one of his most potent weapons; comic analogy: “‘My country, right or wrong’, is a thing that no patriot would think of saying except in a desperate case. It is like saying, ‘My mother, drunk or sober’. No doubt if a decent man’s mother took to drink he would share her troubles to the last; but to talk as if he would be in a state of gay indifference as to whether his mother took to drink or not is certainly not the language of men who know the great mystery.” As frequent a target of Chesterton’s wit as complacent oafs who govern badly, was a group at whose hands we suffer today as never before; progressive reformers of limited vision who believe the surest way forward is to heedlessly trash what has come before. Here is a particularly rich analogy Chesterton penned in 1905 to illustrate his abiding belief that in all likelihood, our predecessors and elders weren’t complete idiots and probably had very good reasons for seeing and outfitting the world around them in the way that they did. “Suppose that a great commotion arises in the street about something, let us say a lamp-post, which many influential persons desire to pull down. A grey-clad monk, who is the spirit of the Middle Ages, is approached upon the matter, and begins to say, in the arid manner of the Schoolmen, “Let us first of all consider, my brethren, the value of Light. If Light be in itself good ...” At this point he is somewhat excusably knocked down. All the people make a rush for the lamp-post, the lamp-post is down in ten minutes, and they go about congratulating each other on their unmedieval practicality. But as things go on they do not work out so easily. Some people have pulled the lamp-post down because they wanted the electric light; some because they wanted old iron; some because they wanted darkness, because their deeds were evil. Some thought it not enough of a lamp-post; some too much; some acted because they wanted to smash municipal machinery; some because they wanted to smash something. And there is war in the night, no man knowing whom he strikes. So, gradually and inevitably, today, tomorrow, or the next day, there comes back the conviction that the monk was right after all, that all depends on what is the philosophy of Light. Only what we might have discussed under the gas-lamp, we now must discuss in the dark.” CHESTERTON'S LIFELONG CONVICTION that whenever possible we should resist the impulse to tear structures down and start over from scratch, also pertained – indeed, particularly pertained – in the matter of religion. I initially worried that in joining the Catholic Church and aligning myself with this most tradition-bound of all earthly institutions, I might simultaneously be committing an act of contemporary defection that would somehow take me out of the life that was mine to live in the here and now. More than anyone else, it was Chesterton who showed me that when cynics dismiss tradition as “the dead hand of history” – as this leaden imposition of defunct conventions and outdated mores that only obstructs our progress and needs to be jettisoned forthwith – they were not in fact propounding some wonderful unshackling but a crippling amputation that would hobble any hope of real progress. He understood that the most fruitful way to proceed was not to discard tradition and replace it with something new, but to employ it to build something better. A full fourteen years before crossing the Tiber himself, Chesterton praised the Catholic Church for getting this formula right in a column for The Nation about Cardinal Newman’s An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine. “A man who is always going back and picking to pieces his own first principles may be having an amusing time but he is not developing as Newman understood development. Newman meant that if you wanted a tree to grow you must plant it finally in some definite spot. It may be (I do not know and I do not care) that Catholic Christianity is just now passing through one of its numberless periods of undue repression and silence. But I do know this, that when the great flowers break forth again, the new epics and the new arts, they will break out on the ancient and living tree. They cannot break out upon the little shrubs that you are always pulling up by the roots to see if they are growing.” Chesterton understood that honouring tradition is not some cowardly expression of nostalgia. You aren’t hiding out in the past because you’re too scared to confront some present predicament. You are mustering seasoned recruits to take part in the present struggle. Or as Chesterton expressed this in 1908: “Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about. All democracies object to men being disqualified by the accident of birth; tradition objects to their being disqualified by the accident of death.” That is another quote that precedes Chesterton’s entry into the Catholic Church by more than a decade but look how perfectly it chimes with this explanation given by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger in a 1997 interview when he was asked what part tradition plays in the ongoing life of the Church: “The Church lives not only synchronically but diachronically as well. This means that it is always all – even the dead – who live and are the whole Church, that it is always all who must be considered in any majority in the Church . . . The Church lives her life precisely from the identity of all the generations, from their identity that overarches time, and her real majority is made up of the saints. Every generation tries to join the ranks of the saints, and each makes its contribution. But it can do that only by accepting this great continuity and entering into it in a living way.”  Sailing to second U.S. lecture tour, 1930 Sailing to second U.S. lecture tour, 1930 The adjective most frequently employed to describe G.K. Chesterton’s phenomenal literary productivity is “inexhaustible”. In 1910 alone he published five separate volumes: one novel, The Ball and The Cross; an extended summarization of his political and sociological convictions called What’s Wrong with the World; his biography / critical study of William Blake; and two compendiums of essays, Alarms and Discursions and Five Types. Every year of his publishing life at least one collection would appear of the best of the essays he routinely published in a dozen different magazines and papers. Through the 1980s and 90s, Ignatius Press published the 37 separate volumes that made up their G.K. Chesterton: Collected Works. Typically each volume in that heroic edition comprises what had originally been four or five separate books. The volume I most treasure is number XI which contains eleven different plays by Chesterton (I’d previously heard of three of them and been unable to find copies of any) and all of his writings about his good friend and philosophical adversary, George Bernard Shaw. A full ten of those 37 volumes are devoted to just the essays he contributed to The Illustrated London News from 1905 to 36, the vast majority of which had never previously been reprinted. His 31-year run in the Illustrated News spanned precisely one half of his entire life and those ten volumes provide an excellent survey of the way in which his thinking developed throughout his maturity. But we won’t really have a collected edition that even begins to exhaust the inexhaustible until some suicidal publisher recklessly decides to gather up the 12 years of weekly essays he contributed to the The Daily News from 1901 to 1913 (a collection that would chart his increasing disenchantment with the Liberal Party whose house organ it was) or the occasionally interrupted 25-year run of the more radical Eye Witness started up by his younger brother, Cecil Chesterton in 1911. A bankruptcy motion occasioned the paper’s re-dubbing in 1912 as The New Witness and then it passed into Gilbert’s editorial hands following Cecil’s death in World War I and was latterly known as G.K.’s Weekly until it closed up shop for good shortly after Gilbert’s death. If it hadn’t been for Chesterton’s love for his more hot-headed brother and his ardent wish to pay lasting homage after Cecil’s premature death, I doubt that Gilbert’s commitment to perpetuating this predominantly political paper would have been so absolute. Certainly those who loved Gilbert best and wished him to achieve the finest work of which he was capable, regarded the multi-named paper as a distraction that drained off energy that could have been put to better use. (That last, self-referential name, by the way, was forced on the unassertive G.K.C. by the paper’s anxious accountants who saw it as their best chance to achieve something approximating solvency.) But the lost and scattered writings I would most like to see gathered up are those he contributed as a teenager to The Debater, a student paper with a circulation of about 100, which he and a handful of chums in the Junior Debating Club started up when they were attending St. Paul’s School in Hammersmith, London. (And for the sake of completion, perhaps they could throw in as an appendix Chesterton’s very first, never-published book, The History of Kids which John Sullivan tells us in a 1974 essay, “was dictated to an aunt at the age of three, the transcript signed by his father.”) In his 2008 study, Chesterton and the Romance of Orthodoxy, William Oddie focuses on Chesterton’s coming of age and devotes nearly 50 deliciously detailed pages to the activities of the Junior Debating Club.  Junior Debating Club [GKC: front row centre] Junior Debating Club [GKC: front row centre] These perpetually hungry Victorian boys gathered together in one another's homes after school and through the holidays to gorge themselves on tea and buns and books and enthusiastically recorded their every discovery and breakthrough in the pages of their paper. A three-hour reading of the poetry of Walt Whitman so elevated their spirits that they described it as a ‘séance’. As middle-aged men they would hold jolly reunions of their club in hotel meeting rooms and – a few sheets to the wind, no doubt – would prop each other up as they bellowed out their club song, set to the tune of My Darling Clementine: I’m a member, I’m a member, Member of the JDC I’ll belong to it forever, Don’t you wish that you were me? In sharp contrast to the curiosity and high spirits that drove the JDC, was Chesterton’s demeanour in the classroom. Unnaturally subdued and inattentive in class, he only spoke if he was deliberately summoned and, more often than not, had to admit that he hadn’t been paying attention and could the teacher please repeat the question. On the page, he wasn’t much better focused and was inclined to run off on supplementary tangents that missed the main point of any given assignment. Indeed, he actually had some teachers who thought he might be a moron. A perpetual doodler in margins, his skills as a sketch artist were pronounced. Friends who cared about the pristine condition of their books would not lend them to Chesterton lest they come back irretrievably illuminated. In an essay on Chesterton in his Lives of The Wits, Hesketh Pearson quotes Chesterton’s mother as saying, “I always give money to pavement artists, as I am quite certain that is how Gilbert will end.” He certainly seemed to be unteachable in any ordinary sense and the dreamy and distracted boy (who actually was beanpole-thin in his adolescence) was once reamed out in front of the entire class by an exasperated form master who said, “You know, Chesterton, if we could open your head, we should not find any brain but only a lump of white fat.” But his friends who knew what he was capable of in the extra-curricular realm – and who repeatedly appointed him as the leader of their club and editor of their paper because he was the one who gave their enterprise most of its direction and drive – held a much truer valuation of his extraordinary gifts. Oddie reprints an early essay on dragons which Maisie Ward had merely cited in her biography, saying that its arrival in the pages of their homespun periodical caused his chums to look up with arched eyebrows to proclaim, “This is literature.” THIS REMARKABLE ESSAY by a barely 16 year-old Chesterton opens thus: “The dragon is certainly the most cosmopolitan of impossibilities. His eccentric figure has walked through the romances of all ages and all nations. It is a noticeable fact that many races, far separated by oceans and by ages and differing in language, customs and surroundings, have nevertheless evolved similar creatures in the realm of the imagination. In nearly all legends, Greek, Norse, Celtic, Semitic, Medieval, and Japanese, this scaly intruder has appeared from the earliest times, and appeared apparently with the sole object of being killed, whether by the lance of St. George, the club of Herakles, the sword of Siegfried, or the arrows of Hiawatha . . .” William Oddie marvels that not only is the brilliant wordplay that would always be a highlight of Chesterton’s writing already evident here, but also notes how this essay’s conclusion seems to portend what would turn out to be his literary mission statement: “It is almost as though he has always known that his life was to be spent doing battle with dragons,” writes Oddie. “Already, he was on the lookout for them; and already he had identified them as being representatives of the prevailing culture." This early essay concludes that the modern dragon has become more circumspect: “He doesn’t see the good of going about as a roaring lion, but seeks what he may devour in a quiet and respectable way, behind many illustrious names and many imposing disguises. Behind the scarlet coat and epaulettes, behind the ermine tippet and the counsellor’s robe, behind, alas, the black coat and white tie, behind many a respectable exterior in public and in private life, we fear that the dragon’s flaming eyes and grinning jaws, his tyrannous power, and his infernal cruelty, sometimes lurk. “Reader, when you or I meet him, under whatever disguise, may we face him boldly, and perhaps rescue a few captives from his black cavern; may we bear a brave lance and a spotless shield through the crushing melee of life’s narrow lists, and may our wearied swords have struck fiercely on the painted crests of Imposture and Injustice when the dark Herald comes to lead us to the pavilion of the King.” The poet Walter de la Mare (1873–1956), one year older than Chesterton and therefore not part of his circle, was also enrolled at St. Paul’s School where he sang in the choir until his voice broke. Did he hoard old copies of The Debater in some cupboard? Did this old essay possibly influence de la Mare as he composed a quatrain in tribute of Chesterton in which he outfitted his subject with the accoutrements of a noble slayer of dragons? Chesterton’s widow Frances, included de la Mare’s verse on her husband’s funeral card: Knight of the Holy Ghost, he goes his way Wisdom his motley; Truth his loving jest; The mills of Satan keep his lance in play, Pity and innocence his heart at rest. Unlike nearly all of his friends on The Debater, when their time at St. Paul’s School was done, Chesterton did not go on to academic studies at one of the big universities but instead enrolled at the Slade School of Art. In signing on for an education in art, I think he was hoping that a curriculum which emphasized the work of his hands over the work of his brain, would allow him more leeway to follow his own intellectual instincts and enthusiasms. While no instructor declared him a dunce at the Slade, he made no deep and lasting friendships there and expended much of his energy in resisting the decadence and nihilism affected by so many of his instructors and fellow students. Looking back on his student years in a chapter of his autobiography which is subtitled How to Be a Lunatic, Chesterton writes of the psychological and moral rot which he sensed was baked in to the then-prevailing artistic fashion of Impressionism: “I think there was a spiritual significance in Impressionism, in connection with this age as the age of scepticism. I mean that it illustrated scepticism in the sense of subjectivism . . . Whatever may be the merits of this as a method of art . . . it naturally lends itself to the metaphysical suggestion that things only exist as we perceive them, or that things do not exist at all. The philosophy of Impressionism is necessarily close to the philosophy of Illusion. And this atmosphere also tended to contribute, however indirectly, to a certain mood of unreality and sterile isolation that settled at this time upon me; and I think upon many others.” Chesterton soon came to realize that he did not have the disposition or appetite to become a full-on visual artist and wasn’t that interested in developing his sketching talents further. His brother said of him that “he shrank from the technical toils of art as he has never shrunk from the technical toils of writing.” William Oddie speculates that he may have enrolled at the Slade as an act of filial homage. The shy and broad-minded Edward Chesterton, an easygoing realtor by day with the family firm of Chesterton Estate Agents (which still operates today in parts of London) was himself a dab cartoonist and some of Chesterton’s earliest memories centre on the fun they had creating a toy theatre and populating it with cardboard heroes and villains and – yes – dragons. Right up until his death, Edward Chesterton kept amazingly elaborate scrapbooks of newspaper clippings, publishers’ advertisements, playbills and other ephemera concerning the progress of his oldest son’s career, suggesting that the vicarious investments of this father / son team moved both ways. For his second and final year of higher education, Chesterton left the Slade for its affiliated University College where he majored in history and political economy. William Oddie notes that, “One of his professors later remarked that when Chesterton was at the Slade he always seemed to be writing and when he was listening to lectures on other subjects he was always drawing.” While he didn’t have to spend so much time that second year fending off what he instinctively regarded as poisonous ideologies, he didn’t see that it was doing him much good either and Chesterton packed in formal education altogether in the spring of 1895 without earning any sort of degree. FOR THE NEXT SIX YEARS – until he got married – Chesterton worked as a publisher’s assistant, primarily at the house of Fisher-Unwin and, on the side, continued writing and started to land occasional and often unsigned book reviews in literary periodicals like The Academy, The Quarto, The Bookman and The Speaker. Throughout this whole period of philosophical testing and questing, Chesterton keenly felt the loss of day to day fellowship with his old friends from the Junior Debating Club. In a little poem in one of his notebooks he wrote: Tea is made; the red fogs shut round the house but the gas burns. I wish I had at this moment round the table A company of fine people. Two of them are at Oxford and one in Scotland and two at other places. But I wish they would all walk in now, for the tea is made.  The draughtsman's signature The draughtsman's signature Maisie Ward fruitfully devotes an entire chapter in her biography to the notebooks and letters he was writing at that time. In these dashed-off musings from his late adolescence and early manhood, we can trace the formation of this genius in-the-bud as he sorts his way through the prevailing intellectual fashions of the day and respectfully pushes himself away from the wispy Unitarianism espoused by his classically liberal parents and tentatively, fitfully, contemplates the attractions of a more traditional and rigorously defined Christianity. The notebooks are a place where he can take ideas for a walk, just to see where his mind wants to go. He entitles a short poem, Parables: There was a man who dwelt in the east centuries ago, And now I cannot look at a sheep or a sparrow, A lily or a cornfield, a raven or a sunset, A vineyard or a mountain, without thinking of him; If this be not to be divine, what is it? To fellow JDC member E.C. Bentley (who went on to write the seminal detective novel, Trent’s Last Case) a 20 year-old Chesterton wrote about a transcendental experience he underwent at this time: “Inwardly speaking, I have had a funny time. A meaningless fit of depression, taking the form of certain absurd psychological worries, came upon me, and instead of dismissing it and talking to people, I had it out and went very far into the abysses, indeed. The result was that I found that things, when examined, necessarily spelt [italics mine] such a mystically satisfactory state of mind, that without getting back to earth, I saw lots that made me certain it is all right. The vision is fading into common day now, and I am glad. The frame of mind was the reverse of gloomy, but it would not do for long. It is embarrassing, talking with God face to face, as a man speaketh to his friend.” How characteristic that this natural-born man of letters, who was beginning to discern an imperative to commit himself to ‘the Word that was made flesh and dwelt among us’, should, in a time of spiritual crisis, construe signs of reassurance and hope by what they ‘spelt’. And just as characteristically, within a couple days he followed up that letter to Bentley with another note in which he recast his divine encounter as a joke: “A cosmos one day being rebuked by a pessimist, replied, ‘How can you, who revile me, consent to speak by my machinery? Permit me to reduce you to nothingness and then we will discuss the matter.’ Moral: You should not look a gift universe in the mouth.” If I should ever be granted an audience with Chesterton for 30 seconds, once I’d thanked him for all those marvelous books, I would like to tell him a variation on this joke that I heard from my friend Doug Moore. In this one the pessimist tells God that anyone could have made a better world than this one and as he bends down to scoop up a clump of earth to show Him how it might be done, God grabs him by the arm and says, “Hey, get your own damn dirt.” So here at the exploratory and sporadic outset of his life as a professional writer, we see that Chesterton has fastened onto the single most foundational idea that will, overtly or subtly, inform virtually every article and poem and book that he writes until the end of his days. And that is that all life – that existence itself – is a gift. And that every gift has a giver. And that giver deserves thanks.  GKC receives the gift of a dandelion GKC receives the gift of a dandelion When Chesterton later reflected on how he eventually came to Christian belief, he recalled dabbling in spiritualism and Ouija boards just long enough to get sickened, to attain what he called ‘a bad smell in the mind’. There were dark powers to be tapped into but Chesterton knew enough to know that he wanted nothing more to do with them. He turned and walked away, shut that door for good. But still he was spiritually hungry. He hung onto the idea of God by what he called ‘a thin thread of thanks’. He didn’t particularly hunger for Heaven or righteousness or salvation. All he really wanted was someone to say thank you to. That enormous impulse of gratitude is, I suspect, fairly rare. If you don’t feel it in any measure, then I expect that Chesterton is not your man. Chesterton found that when he begin to cultivate gratitude for life itself, he received yet another quite unexpected gift. It brought him peace of mind. He no longer had cause to go tumbling into psychological abysses. Whereas Impressionism had fostered an ever-shifting subjectivism where things only existed as he perceived them, or might not even exist at all, gratitude for life fostered a rock-solid sense of reality. He now was able to take it on trust that things really are what they are. I’m reminded of that rather strange expression we have: “Let’s take that as a given.” What we mean by that, is that there’s no getting around a given. It commands a sort of precedence in that it must be acknowledged and taken into proper account before you can proceed or try to build anything more at all. And this Chesterton was now prepared to do. He gratefully acknowledged that he was the blessed recipient of the greatest gift there was.  Frances Blogg Frances Blogg If he didn’t yet know precisely in which creedal direction he would be expressing all the gratitude that was suddenly flooding his heart, he figured that out in a trice when he fell in love at first sight with a woman who wore a simple crucifix around her neck; a woman he said who practised her Anglo-Catholic religion with the same no-nonsense efficiency as she tended her garden. He was sure he’d known happiness before he met Frances Blogg but nothing like this. When he knew his love was returned and that their future would be together, he wrote her a third person narrative outlining his previous life and concluded it like this: “There are four lamps of thanksgiving always before him. The first is for his creation out of the same earth with such a woman as you. The second is that he has not, with all his faults, ‘gone after strange women’. You cannot think how a man’s self-restraint is rewarded in this. The third is that he has tried to love everything alive: a dim preparation for loving you. And the fourth is – but no words can express that. Here ends my previous existence. Take it: it led me to you.” There was really only one more thing that needed to fall into place before the full literary phenomenon of G.K. Chesterton could be properly launched onto an unsuspecting world. This wildly impractical wizard of words needed a manager; someone who could organize and guide his professional affairs, and see that he met his deadlines and got to necessary meetings in good time and was appropriately turned out when he did so. Ideally he would acquire a manager who recognized his true value and cared for him enough not to exploit him but, of course, managers like that don’t exist. But wives do. Maisie Ward writes: “One of Gilbert’s friends remarked that Gilbert’s life was unique in that, never having left home for a boarding school or University, he passed from the care of his mother to the care of his wife. I think, too, that the degree of his physical helplessness affected all who came near him with the feeling that while he might lead them where he would intellectually, it was their task to look after a body that would otherwise be wholly neglected.” Frances’s widowed mother was so leery of the shambolic weirdo with a low-paying job who was courting her daughter, that it took her three years until she was sufficiently convinced of her would-be son-in-law’s prospects, to let the wedding go ahead. I consider it a real testament of Chesterton’s chivalric heart that not only did he not lace Mrs. Blogg’s tea with a sprinkling of arsenic so as to speed things along, he wrote his fiancé a letter like this midway through their protracted betrothal: “I cannot profess to offer any elaborate explanation of your mother’s disquiet but I admit it does not wholly surprise me. You see I happen to know one factor in the case, and one only, of which you are wholly ignorant. I know you . . . I know one thing which has made me feel strange before your mother – I know the value of what I take away. I feel (in a weird moment) like the Angel of Death . . . . Oh, dearest, dearest Frances, let us always be very gentle to older people. Indeed, darling, it is not they who are the tyrants, but we. They may interrupt our building in the scaffolding stages: we turn their house upside down when it is their final home and rest. Your mother would certainly have worried if you had been engaged to the Archangel Michael (who, indeed, is bearing his disappointment very well): how much more when you are engaged to an aimless, tactless, reckless, unbrushed, strange-hatted, opinionated scarecrow who has suddenly walked into the vacant place. I could have prophesied her unrest: wait and she will calm down all right, dear. God comfort her: I dare not.”  GKC and Frances GKC and Frances And with their wedding in June of 1901, Frances firmly took her husband in hand, decked him out in new togs that included a dashing brigand’s hat and cloak – perhaps even smashed a bottle of champagne over his head - and the good ship G.K.C. finally set out in full-time sail on journalism’s open sea. He quickly made a splash as an essayist and literary critic, writing in that highly flamboyant and personal style, that seized the attention of readers and editors who clamoured and negotiated for more. As we have seen, Chesterton’s mind was always wide open to distractions and different facets of any subject he tackled and by quickly over-committing himself to virtually any newspaper or magazine that came calling, he began to take on the persona of the absent-minded genius which became so large a part of his legend. In other books and articles of the period, one is always coming across sightings of Chesterton: halting traffic on Fleet Street as he stands in the middle of the road scribbling on bits of paper; distractedly ordering dinner in restaurants while debating with his friends, then letting that dinner go cold; once misplacing a fried egg which he swept off the table while gesturing to make a point; dining at the House of Commons with a boot on one foot and a slipper on the other (perhaps his dresser wasn’t feeling up to snuff that day); stopping himself cold in town one afternoon, certain he was forgetting an appointment and wiring home to Frances: “Am in Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?”  GKC as decked out by Frances GKC as decked out by Frances But Chesterton’s absence of mind in daily affairs only evinced his astonishing presence of mind in other matters. Imagine the shock of the bored journalist who asked this dithering eccentric what book he’d take to the proverbial desert island and Chesterton calmly answered: “I think I should take Thomas’ Guide to Practical Shipbuilding.” (It wasn’t just a brilliant riposte; he named an actual book.) Asked in a public debate to comment on the apparent success of the female enfranchisement movement, Chesterton gave spontaneous utterance to the kind of zinger that most writers could spend a week constructing and polishing: “Twenty million young women rose to their feet with the cry, ‘We will not be dictated to,’ and promptly became stenographers.” Lecturing once on Dante’s Inferno at Notre Dame College in the States, he dealt at some length with a supplementary question and then tried to get back on track by asking, “Now, where in Hell were we?” On the page, levity and fun are almost always part of the proceedings but the insights go deeper, ranging from the fairly straightforward (“There is more simplicity in the man who eats caviar on impulse than the man who eats grape-nuts on principle”) to the cockamamie (“The relations of the sexes are mystical, are and ought to be irrational. Every gentleman should take off his head to a lady”) and from the paradoxical (“For children are innocent and crave justice, while most of us are wicked and naturally prefer mercy”) to the profound (“The whole difference between construction and creation is exactly this: that a thing constructed can only be loved after it is constructed, but a thing created is loved before it exists”). There are single paragraphs in Chesterton’s work (and one’s coming up right now; a tangent hailing from his critical study of Charles Dickens) that contain more original ideas than most writers manage to juggle in a book: “People talk with a quite astonishing gravity about the inequality or equality of the sexes; as if there possibly could be any inequality between a lock and a key. Wherever there is no element of variety, wherever all the items literally have an identical aim, there is at once and of necessity, inequality. A woman is only inferior to a man in the matter of being not so manly; she is inferior in nothing else. Man is inferior to woman in so far as he is not a woman; there is no other reason. And the same applies in some degree to all genuine differences. It is a great mistake to suppose that love unites and unifies men. Love diversifies them because love is directed toward individuality. The thing that really unites men and makes them like to each other is hatred. The more modern nations detest each other, the more meekly they follow each other; for all competition is in its nature only a furious plagiarism. As competition means always similarity, it is equally true that similarity always means inequality. If everything is trying to be green, some things will be greener than others; but there is an immortal and indestructible equality between green and red.” As I say, that paragraph is a flourish off to the side of his main subject. Early on in the book – and writing at a time when not so much was known about Dickens’ appalling treatment of his wife nor the tetchiness of his relations with his publishers and professional colleagues – Chesterton latched onto a situation from Dickens’ infancy and brilliantly employed it as a kind of template for his entire life and career. Commenting on how Dickens’ father used to get the boy to sing songs and provide entertainment for his elders, Chesterton writes: “Some of the earliest glimpses we have of Charles Dickens show him to us perched on some chair or table singing comic songs in an atmosphere of perpetual applause. So, almost as soon as he can toddle, he steps into the glare of the footlights. He never stepped out of it until he died . . . Dickens had all his life the faults of the little boy who is kept up too late at night. The boy in such a case exhibits a psychological paradox; he is a little too irritable because he is a little too happy. Like the over-wrought child in society, he was splendidly sociable, and yet suddenly quarrelsome. In all the practical relations of his life he was what the child is in the last hours of an evening party, genuinely delighted, genuinely delightful, genuinely affectionate and happy, and yet in some strange way fundamentally exasperated and dangerously close to tears.” Chesterton’s biography of Dickens was an enormous commercial and critical success, his first real breakthrough, and inspired one typical reviewer (almost echoing his old chums in the JDC) to declare that it, “marks the definite entry of its author into the serious walks of literature.” The book not only established Chesterton; it re-established Dickens, as marked by the publication the very next year of the Everyman edition of Dickens’ entire oeuvre, with specially commissioned introductions by Chesterton to all two dozen volumes.  Chesterton: natural born man of letters Chesterton: natural born man of letters When you pick up a book by G.K. Chesterton you are imbibing stories and essays – often journalism – that is 85 to 120 years old. How can it still be interesting, so applicable to life and the world as we know them today? Only because the man unfailingly bypassed almost everything we think of as ‘news’ and wrote instead about all those trivial and cosmic matters that will fascinate and bedevil the human race unto extinction – like books and ideas, religion and love, beer and skittles, cheese and croquet. Nothing was too common or insignificant to look at it again with new eyes. The fact that anything was taken for granted or overlooked was, for Chesterton, a flashing signal that he’d probably stumbled upon something here of fundamental importance. I give you some essay titles selected at random: On Lying in Bed (How’s this for an irresistible opening sentence? “Lying in bed would be an altogether perfect and supreme experience if only one had a coloured pencil long enough to draw on the ceiling”); What I Found in My Pocket; On Running After One’s Hat (an activity which Chesterton claimed was only slightly less embarrassing than running after one’s wife); Logic and Lawn Tennis; The Glory of Grey . . . you get the idea. Chesterton loved the rough and sloppy world of journalism, regarded himself as a journalist first and a serious writer not at all. “I would rather live now and die, from an artistic point of view,” he said, “than keep aloof and write things that will remain in the world hundreds of years after my death.” He liked journalism’s immediacy of response, the give and take, and the tussling with an enormous audience. When book contracts started to come his way, he wouldn’t scale back his journalistic commitments and his appalling working habits didn’t change either. In preparation for his numerous biographies of writers and saints, he would routinely get his secretary to gather together mountains of pertinent material and after the most desultory of scans, he would plough ahead and write the books mostly from memory and rumination. “Anything worth doing is worth doing badly,” he said by way of explaining how even his own autobiography is riddled with incorrect dates and incidents out of sequence. He was scarcely more careful when writing about other men’s lives and many of those biographies come with a fair share of the kind of mistakes that are known to give more punctilious librarians the hives. When George Bernard Shaw reviewed Chesterton’s 1909 book length study of him in The Nation, he enthused that it was “the best work of literary art that I have yet provoked,” but then threw in this qualifier: “Everything about me which Mr. Chesterton had to divine he has divined miraculously. But everything that he could have ascertained by reading my own plain directions on the bottle, as it were, remains for him a muddled and painful problem.” The value of those books when they worked – and no one denies the brilliance of his Dickens, Browning, St. Francis or Thomas Aquinas – wasn’t their biographical veracity (the strokes were much too broad and reckless for that) as their author’s uncanny ability to isolate and magnify the important truths that no one had ever latched onto before. Etienne Gilson, the renowned Thomistic scholar who devoted entire volumes to single facets of Aquinas’ life and thought, greeted the appearance of Chesterton’s 180-page study of the saint by saying, “Chesterton makes one despair. I have been studying St. Thomas all my life and I could never have written such a book.” Chesterton’s two literary surveys, The Victorian Age in Literature (a book which was commissioned and then prefaced with a short disclaimer by the nervous English publishing house of Williams and Norgate), and Heretics, (a book-length dispute with most of the influential writers of the Edwardian era) also display to stunning effect his knack for diving through walls of preconceptions and clichés and emerging with new and essential insights. In the fields of the novel and poetry, Chesterton’s reputation hasn’t fared so well. Poetically he excelled at comic verse and ballads, scoring achievements and popularity in his day but is currently ignored by critics and academics who seem to have this thing against any modern poet who’d exhibit such bad taste as to be a practicing Christian, to cheerfully shun despair and to rhyme. Anthologists such as Kingsley Amis and W.H. Auden always included a few of his verses in their collections but for the most part, Chesterton’s poetry – accessible, populist and rhythmically stirring – couldn’t be more at odds, more delightfully irrelevant to contemporary and dominant poetic trends. Just to give you a taste, let me inflict one of his shorter poems on you, and, in its day more than a century ago, one of his most beloved: The Donkey When fishes flew and forests walked And figs grew upon thorn, Some moment when the moon was blood Then surely I was born. With monstrous head and sickening cry And ears like errant wings, The devil’s walking parody On all four-footed things. The tattered outlaw of the earth Of ancient crooked will, Starve, scourge, deride me; I am dumb I keep my secret still. Fools! for I also had my hour, One far fierce hour and sweet There was a shout about my ears And palms before my feet. Although I cherish many of his novels and stories, I feel a little sorry for anyone who first approaches Chesterton through his fiction. He never created a full character in his life but preferred to dress up ideas in human form and make them fight and dance. While some of his mysteries required that he create the semblance of a plot, these never received half so much of his attention as the weirdly charged atmospheres and settings of these tales and the moral and philosophical debates which ensued at their climax. The Father Brown mysteries were so hugely popular in their day, that they supported both Chesterton’s household and that less than profitable weekly newspaper that bore the first two initials of his name. But nowadays it’s Chesterton fanatics and not your usual mystery buffs who have much use for the Father Brown series at all.  Too bad for them. They’re missing out on some great stuff. Consider this little gem of a speech from The Flying Stars, in which the dashing criminal Flambeau has disappeared into the upper reaches of a stand of trees at night and Father Brown beseeches him from below to give back the diamonds whose theft has framed an innocent young man: “I want you to give them back Flambeau, and I want you to give up this life. There is still youth and honour and humour in you; don’t fancy they will last in that trade. Men may keep a sort of level of good but no man has ever been able to keep on one level of evil. That road goes down and down. The kind man drinks and turns cruel; the frank man kills and lies about it. Many a man I’ve known started like you to be an honest outlaw, a merry robber of the rich, and ended stamped into slime . . . I know the woods look very free behind you, Flambeau; I know that you could melt into them like a monkey. But some day you will be an old grey monkey. You will sit up in your free forest cold at heart and close to death, and the tree-tops will be very bare . . . Your downward steps have begun. You used to boast of doing nothing mean, but you are doing something mean tonight. You are leaving suspicion on an honest boy with a good deal against him already; you are separating him from the woman he loves and who loves him. But you will do meaner things than that before you die.” Chesterton based the character of his priest / detective on his good friend, Fr. John O’Connor, who not only brought first him and (a couple years later) Frances into the Catholic church, but seems to have perpetrated the only known instance of a fictional character writing a book about his author, when he published a delightful memoir of their friendship, Father Brown on Chesterton, the year after Chesterton’s death. Shortly after the two men met at a weekend house party, they set out together on a three-hour conversational ramble on the moors during which Chesterton learned rather more than he thought a priest could possibly know about crime and depravity. He simply hadn’t appreciated – what with the confessional, prison visits, ministering to the injured, the dying and the bereaved – what sort of hair-raising, heart-wrenching scenarios a priest would be privy to. After they got back to the house and dinner and post-prandial chat with several other guests, Fr. O’Connor said his good night and toddled off to bed. Two hearty Cambridge undergraduates then leaned forward in their seats to say, initially, what a fine and intelligent chap he seemed, but then, succumbing to the same pedestrian assumption as Chesterton fell for earlier that day; how artificial it all seemed, and how pitiful in a way, that a priest’s celibate and cloistered existence should keep him in ignorance about the deeper and darker realities of life. Chesterton reflected, “To me, still almost shivering with the appallingly practical facts of which the priest had warned me, this comment came with such a colossal and crushing irony, that I nearly burst into a loud harsh laugh in the drawing room. For I knew perfectly well that, as regards all the solid Satanism which the priest knew and warred against with all his life, these two Cambridge gentlemen (luckily for them) knew about as much of real evil as two babies in the same perambulator.”  Alec Guiness as Father Brown Alec Guiness as Father Brown Some of his novels – like The Napoleon of Notting Hill, The Man Who Was Thursday and The Ball and The Cross – take the form of elaborately weird existential comedies and read like the work of a decidedly non-suicidal Franz Kafka. Of all his novels, my own favourite is Manalive in which the Chestertonian stand-in of a main character named Innocent Smith is hauled into court on charges of burglary, bigamy and attempted murder. But the only house he breaks into is his own in a bid to revive the thrill of ownership. The woman he elopes with is his wife so he can taste again the ecstasy of first love. And the only people he points his pistol at are dreary mopes who say they’re tired of life until Smith presents them with the possibility of losing it. Maisie Ward calls Manalive the Chestertonian acid test; if you can stand it, you can stand anything he wrote. He is so cheerful, so funny, so brilliant in this book, that he’s obnoxious. His best-selling books today are his two greatest works of Christian apologetics, Orthodoxy (which he called his ‘slovenly’ spiritual autobiography) and The Everlasting Man, (a God-centred history of the world; his answer to H.G. Wells’ Outline of History). These books stand alone with some of the books of C.S. Lewis (who himself was profoundly influenced by Chesterton) as the best Christian apologetics of the 20th century. For those with a taste for more specifically Catholic apologetics, I would also recommend The Well and the Shallows and The Thing. I treasure this illuminating—and, of course, paradoxical—excerpt from The Thing whenever I am being badgered by some secularist who condemns Christianity for its life-choking gloominess and unhealthy preoccupation with guilt and sin: “The Fall is a view of life. It is not only the most enlightening, but the only encouraging view of life. It holds, as against the only real alternative philosophies, those of the Buddhist or the Pessimist or the Promethean, that we have misused a good world, and not merely been entrapped in a bad one. It refers evil back to the wrong use of will; and thus declares that it can eventually be righted by the right use of will. Every other creed but that one is some form of surrender to fate.”  GKC and Frances at Top Meadow GKC and Frances at Top Meadow Let me leave you with a final note about ‘paradox’. It is another of those words, like ‘inexhaustible’, that is much associated with Chesterton. The term denotes an apparent contradiction which on closer inspection turns out to be oddly complementary and even meaningful. And the only books I know which pack as many paradoxes to the page as just about any book of Chesterton’s are some of those which we find in The Holy Bible. Whereas a mere contradiction just cancels itself out in an act of linguistic hari-kari and is thought of no more, the constituent elements in a good rich paradox emphasize and intensify each other until they start vibrating with the multi-faceted beauty of lively co-existence and take up permanent residence in our consciousness. Chesterton’s uncanny knack for coining paradoxes is either celebrated as one of his hallmarks or condemned as a tiresome trick. The sad truth is that not everybody cares for these verbal explosions of compounded meaning and I think that might explain why Chesterton actually bewilders and irritates some readers. They can’t get a handle on him. They can’t tell when he’s serious. (He’s always serious or, at least, sincere.) They think he writes like he’s on drugs. But as I explained earlier, Chesterton is my literary drug of choice. In his poetry or his prose, his fiction or his essays, at the top of his form or not, I always find in Chesterton an affirmation of life and gratitude for its gift; an unflagging and contagious sense of wonder and amazement at the world in which he lives. Chesterton was fond of recalling an old riddle from his childhood. What did the first frog say when he finally met God? ‘Lord, how you made me jump!’ That too was an exclamation of thanks and a distillation of the wonderful spirit of this man – ungainly, high-spirited, grotesquely beautiful; jumping for joy in the face of God. The Annual Thomas Aquinas lecture, G.K. Chesterton and the Gift of Gratitude, was delivered at St. Peter's Seminary, London Ontario on January 28th, 2019.

1 Comment

Susan Cassan

4/2/2019 08:04:12 am

This article is almost as much a pleasure to read as to hear your Presentation “live” at St. Peter’s. Great introduction to an intriguing author. Looking forward to exploring his works.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed