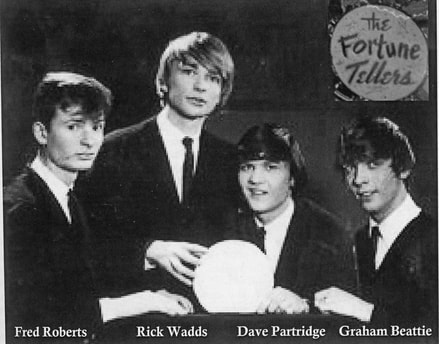

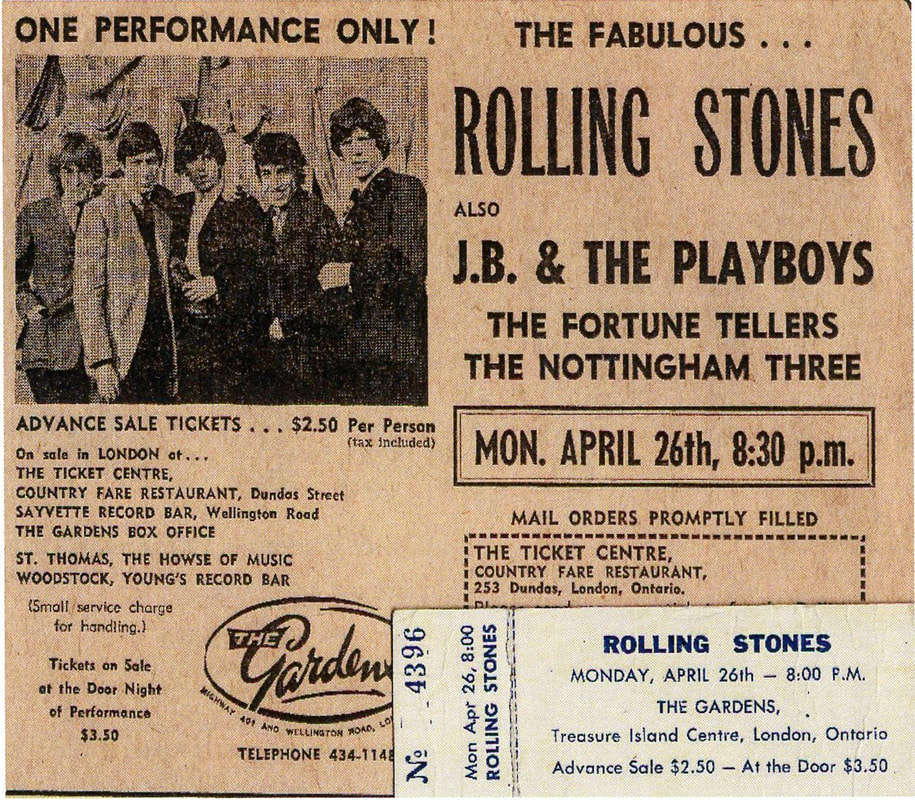

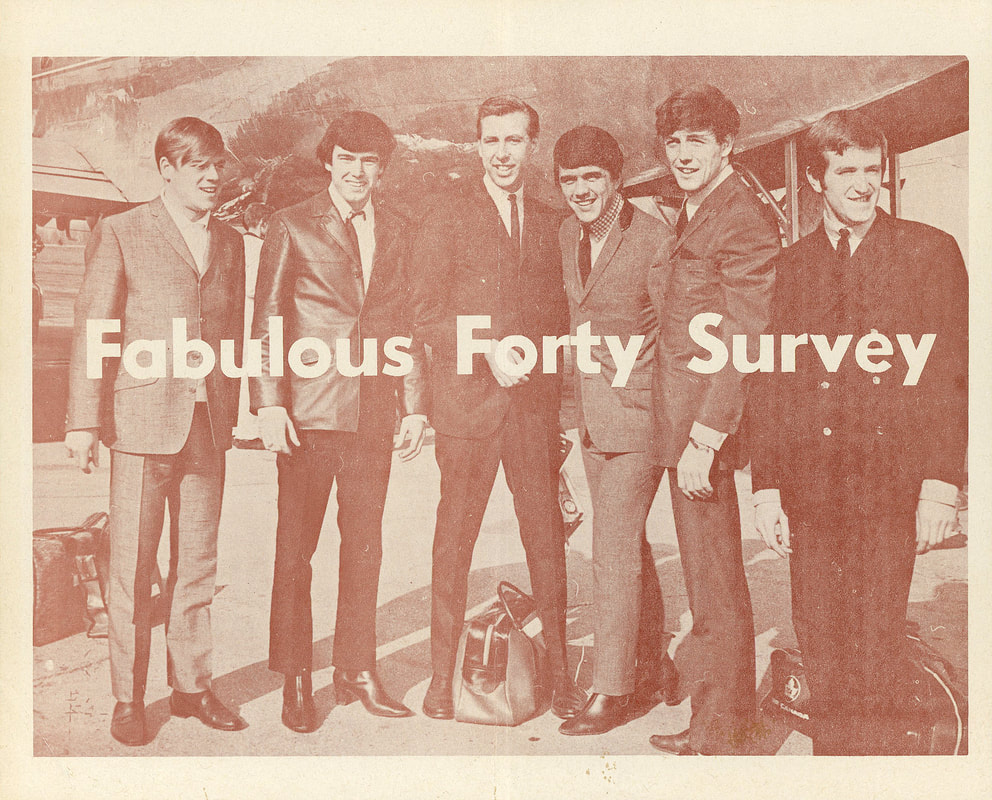

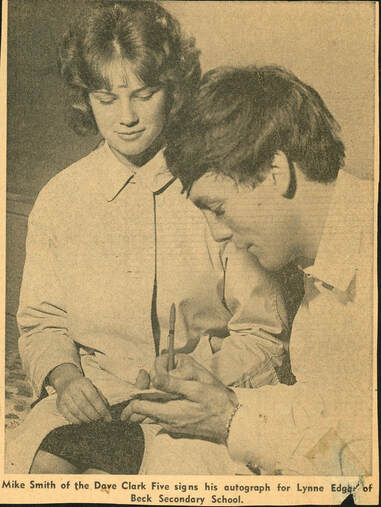

The Fortune Tellers: giants of London '60s music scene The Fortune Tellers: giants of London '60s music scene LONDON, ONTARIO – At summer’s end, Jim Chapman hosted a packed out launch party at Unity of London hall for his long-promised and most lavishly indulgent compendium of London cultural history, Battle of the Bands: London Ontario’s 1960s Teen Music Explosion. This book won’t be everybody’s ticket to dreamland. But for Londoners of the right vintage and aesthetic temperament, this glorious cache of imagery and lore grants magical re-admittance to an age of sensation and delight that most of us assumed was irretrievable until our industrious packrat of an author put in the mind-boggling effort to compile this riveting and shamelessly nostalgic document. Among the lost treasures you will find between the covers of Chapman’s time machine of a book are . . . a listing of and stories about eighty-six different bands from The Agendas to The Yellow Splash (and it just doesn’t matter that butterflies lived longer than some of these bands; in each case the names of all the members and the instruments they played are carefully itemized) . . . photos of the clubs and halls and the arenas, church basements and school gyms where those bands performed as well as the shops where they bought or rented their gear (the prime purveyor during this period was unquestionably John Bellone) . . . also pictured are the cars, hearses, vans and miscellaneous rattletraps that transported these musical collectives to their gigs . . . a veritable blizzard of papery ephemera like business and Musicians’ Union cards, concert posters, and weekly Fabulous Forty Surveys (available for free at also-pictured and long-vanished record stores like The Disc Shop and Bluebird) . . . promo photos of extravagantly coiffed lads (and occasional lasses) decked out in their very snappiest outfits as they pose in front of or on top of London locales and landmarks like Victoria Park’s Holy Roller . . . and loads of concert photos replete with vintage guitars, drum kits and organs whose every note and chord and strum and smack were projected to the back of the hall by humming stacks of warm amps and swirling Leslies. In its loving documentation of all the ways in which young Londoners embraced a particularly resonant era in popular music, does the book pretty well lack any pretense of critical detachment? Oh gosh, yes. And by packing nearly one thousand images and two hundred-thousand words onto two hundred and thirty pages, has our author committed occasional ocular challenges to the capacities of many of his likeliest readers; by which I mean those who were lucky enough to be around sixty years ago when bands like The Fortune Tellers and The London Set and The Undertakers were scrambling their way onto any excuse for a bandstand they could find? You betcha. Here are some tips to help the reader more fully imbibe what this book has to offer. To really set the mood and maximize the Proustian buzz of your reading experience, I recommend getting your nose involved. I know it’s unlikely that you can still put your hand on a bottle of Jade East or Brut. But perhaps you can dig out a gummy vial of patchouli oil from the darkest corner of your sock drawer and see if the stopper hasn’t become too congealed to unscrew after a half century’s neglect. For scanning the not-overly-large text which commonly runs across the page for ten and a half unbroken inches, setting a ruler beneath each line as you read greatly improves the odds that your eyes will land on the correct, subsequent line when flying all the way back over to the left margin. And in addition to my usual reading specs, I further embiggened the proceedings with a Sherlock Holmes-style magnifying glass. This particularly helped out with ascertaining significant details in the photos, like: was Village Guild guitarist Roy Thompson playing through a Fender, Marshall or Traynor amplifier? These things are important to know. And what an unexpected treat it was to eagerly zoom in on the almost-forgotten visage of Larry Gray. Who else but Chapman would think to include a short write-up and two photos (one in full-colour clown makeup) of this guy? Larry was a dapper and (let’s be honest) slightly enchanted habitué of every concert of the period who would insinuate himself into very close proximity to the performers by vaguely pretending that he was a manager or promoter of some kind. In the picture on page 73, Larry’s seen talking shop with a gently puzzled Grant Smith, front man for The Power who, the oldsters might recall, scored some chart action with their cover of The Spencer Davis Group’s Keep on Running. Larry’s single boldest act of stage-crashing took place when The Byrds played the old London Arena. To this day I regret that I didn’t catch that show. The Byrds eventually became an important band for me but at the time of their London appearance, the initial impact of Mr. Tambourine Man and Turn, Turn, Turn had worn off and they were erratically experimenting with different styles before hitting their most-perfect stride with the Notorious Byrd Brothers and Sweetheart of the Rodeo albums. Early in their set, Larry materialized on stage, standing in the rim of the spotlight’s glow for a couple of songs (until an actual manager or promoter yanked him off), nodding and beaming away at ‘his boys’ with arms crossed in front of his chest like a preening Ed Sullivan; tickled pink as the latest teen sensation drove the chickadees wild. Needless to say, not just anybody could pull together a book like this. For almost sixty years now, Jim Chapman has been a London-based musician. He was a fresh-faced puppy of fifteen years in 1964 when he first joined forces with three other teenaged chums who called themselves the Arkangels and banged out covers of Wipeout, Walkin the Dog, Pretty Woman, It’s All Over Now and You Really Got Me in church basement ‘teen town’ gigs. His own closest approach to the big time came a few years later, playing bass with his second band, Sally and the Bluesmen which soon morphed into London’s top-rated act, The Bluesmen Revue. After winning a local battle of the bands, the Bluesmen got to cut one uncharacteristically poppy single in New York City for Columbia Records. Spin the Bottle (1968) was assigned to them as were session musicians to supply the instrumentation so as to save precious studio time. Though the song was hardly representative of their R&B style, the Bluesmen at least got to sing on the record and this was only supposed to be the opening salvo in a brilliant career to follow. With no promotion whatsoever, Spin the Bottle sold like hotcakes locally – now there’s a cliché I never hear without remembering my London magazine editor Douglas Cassan’s quip: ‘And when was the last time you bought a hotcake?’ - but didn’t trouble the charts anywhere else. The under-aged band-members never saw a penny in royalties. When their parents (following consultation with London lawyer, Sam Lerner) wouldn’t co-sign the miserly and sketchy contract which had been proffered to the lads, management negotiations soon collapsed, no follow-up records were released and the band broke apart the following year and went their separate ways. If that contract had been signed, would things eventually have worked out for the better? Who knows? In their headstrong grasping for any kind of shot at the top of the pops, it’s all too common for ingénue artists to get royally exploited and ripped off. It was a bitter, dashing come-down and less hardy souls might’ve tossed all musical ambition aside and settled for careers in insurance adjustment instead. But Chapman recounts that virtually everybody in the band found a way to carry on with at least a few toes of one foot stubbornly planted in some segment or other of what Andrew Loog Oldham called, “The Industry of Human Happiness”. (Speaking of record companies famous for stiffing their artists, Oldham’s own Immediate Records was one of the worst.) Chapman certainly kept plugging away and – a little more desultorily, of course - is still at it today. In the second half of Battle of the Bands, subtitled Uncle Jimmy’s Excellent Adventure, Chapman carries on his own story from 1970 to 2023 as an all-round musical scene-maker in more than a dozen subsequent bands, as a song and jingle-writer for hire, a recording studio manager and booking agent for other bands, and as an MC and guest singer for consortiums as various as the Canadian Celtic Choir and the London Tigers baseball team. Put that together with a not quite-as-long career as a radio and TV host and a newspaper and magazine columnist and author, and you can start to appreciate that - except, perhaps, for an occasional introvert who plays the triangle or the tuba - there probably aren’t too many musicians in this town that Chapman doesn’t know. I’m sure there were years when Chapman’s non-musical enterprises out-grossed whatever he made from gigging around Ontario (and occasionally into the States) in a series of bands with seriously brilliant names like The Incontinentals, The Cleverly Brothers and Frankly Scarlet. And I’ll bet the money he’s going to make off this book won’t get him much more than a hamburger and maybe a beer. But money was never the point here and now that munificent pension cheques allow him some leeway - and he still has the energy and brains - I imagine there was considerable satisfaction in pulling together this rollicking account of a bumpy and ingenious trajectory through a milieu that he so abundantly loved and strove to serve with his own kind of integrity and wit. Suddenly I’m remembering an Incontinentals’ gig from about twelve years ago when I was gobsmacked to hear the band send out a note-perfect cover of Come on Down to My Boat by those forgotten one-hit wonders, Every Mother’s Son. Again, who else in the world remembered - let alone cherished - that soap bubble of a hit half a century after it floated off the airwaves and into oblivion? There are a lot of funny stories in here. The most excruciating might be the one when The Bluesmen are cruising down Broadway in New York City at high noon and the hitch comes loose on the trailer they’re hauling and two tons of equipment goes careening toward a pedestrian-packed sidewalk. Chapman imagines a newspaper headline of Angry Mob Attacks Canadian Teens after Runaway Trailer Kills Dozens before an illegally parked car takes the impact instead. Seizing this luckiest of breaks, the lads leave a hastily scratched note with their business manager’s number on the battered car’s windshield, re-hitch their trailer (properly this time) and vamoose. In addition to recounting many passing encounters with some pretty big names like The Rolling Stones, Ronnie Hawkins, Sly & the Family Stone, Carlos Santana and Jimi Hendrix, Chapman expresses much gratitude for the friends he’s played with in so many bands along the way, including in a few of these consortiums, his wife Carlyn (generator of the most radiant smile in show biz) on keyboards and vocals. More than anything else, what set off the explosion of local music-making that Chapman celebrates in this book, was the British Invasion of North America which commenced with The Beatles’ first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in February of 1964. While Chapman’s first band, The Arkangels, were up and running that year, Chapman makes the interesting observation that it wasn’t really until the summer of ’65 that London bands started coming out of the woodwork. I might just be imposing my own limited understanding of what was afoot at the time but I think a case could be made that in the first year and a bit after The Beatles took the world by storm, most people didn’t quite realize how radically and completely the template of popular music had been changed; that there was something much more vital and organic underway here than just another teenaged fad like Chubby Checker and The Twist. Sure, you might want some agents or producers later on if things really started to take off. But this music wasn’t being concocted by faraway impresarios and industry bigwigs. In a way, it was the musical equivalent of regionalism. The new and inspiring model was a small unit of like-minded friends who got together to make their own kind of music just for the fun and the thrill of it all. Though London would never get to host The Beatles, in November of ’64 their equally hairy and equally British chief rivals, The Dave Clark Five, played two shows at the Treasure Island Gardens and my clueless twelve year-old self scratched together the two dollars to attend. The friend I went with had been persuaded by his dad to take along a pair of binoculars which helped a little but not all that much. We were so far away from the stage and with every girl in that big, acoustically challenged arena screaming her head off, I really felt unengaged with this concert that I had so looked forward to. In terms of verisimilitude, this live experience wasn’t a patch on listening to their records or seeing them on TV. At one point, thinking it might somehow make this remote spectacle more tangible, I released a half-hearted scream myself and immediately regretted it, thinking, "No, that's just for girls." In the first half of the book, Chapman mixes up the narrative tone quite nicely by tapping ninety-one different people – mostly musicians but also some fans – to share their memories (usually just a paragraph or two) of the 1960s music scene. While his guests make only passing mention of London’s DC5 show, everybody seems to have a story about the spectacularly disastrous concert which The Rolling Stones didn’t really get to play a mere five months later at that same cement and metal bunker. At that pre-Satisfaction point in their career, the Stones still hadn't scored any monster hits on this side of the pond though they had at least charted four or five times. Five or six songs into their show (one of which, I’m pretty sure, was their beautifully spooky cover of Willie Dixon’s Little Red Rooster) the London police freaked out at the number of girls storming the stage in lust-crazed bids to get close to Mick Jagger or Brian Jones, and unwisely cut off the electricity amplifying their instruments and switched on the house lights. The ever-prudent Jagger then walked out to the rim of the stage and did what he could to stir things up by shouting, "The cops have cut our power. We can't play because the cops have cut the power." That's when the riot ensued - a not uncommon occurrence at Stones' concerts of the period – and people came pouring down from the stands onto the arena floor, roaring their outrage and trampling down flimsy partitions of snow fence which designated different seating sections. I had just helped release one of my friends who was caught underneath a section of that fence (a hideously dangerous predicament that I shudder to recall), when I felt a sharp sensation as the metal leg of a hurled chair dug into the crown of my head. The great thing about head wounds from the twelve year-old male perspective is that while they don't hurt very much, they bleed like veritable geysers. Spilling that much blood at a Stones' concert, I felt like I'd earned my rock & roll spurs. A couple of security guards marched me down to the manager’s office where my wound was cursorily attended to. (“How many fingers do you see, kid? Three? Yeh, you’re fine.”) Incredibly, by today's standards, no one got sued and I didn't even get the cost of my ticket refunded. And shall we chalk it up to mid-60’s inflation that it cost fifty cents more to see the Stones than the DC5? Outrageous. Chapman, of course, has his own story of that concert and it’s a doozy. He and all the rest of the Arkangels were nuts about the Stones and had bought tickets but went along to the arena well before the show to see if they could more informally catch sight of the band. Well, they did much better than that. When some arena functionary briefly opened a back door to check on something or other, the Arkangels were able to catch it before it quite clicked shut, waited a few seconds before slipping inside and hid out in a dirt-floored access area underneath the tiered seats until the arena started to fill up with kids. When they emerged from their hidey hole, they found access to the front of the house had been sealed off and made their way into the backstage area where they briefly enjoyed some face time with Mick Jagger and Bill Wyman and even exchanged small tokens of esteem. After popping one into his own mouth, Wyman gave Arkangels’ drummer, Dave Southern, a Chiclet. Chapman thinks he might still have that chewed-up wad stashed away somewhere but I doubt that very much. If it was still around, you know he’d have carefully squirreled it away in a humidor somewhere and there’d be a picture of it on page 43, right next to Chapman’s never-torn ticket to the show. Then Chapman gave Jagger his band’s business card which the Glimmer Twin took the time to at least pretend to read and encouragingly said, “Good for you,” before slipping it into the pocket of his jacket and then being hustled along by a tour manager. Those oddly touching words of cordiality and encouragement to a sixteen year-old kid from one of the original bad boys of rock, are typical of perhaps the sweetest and most unexpected thing that turns up again and again in this book of musical reminiscences. For all of the competition and swagger and striving to be the hottest player on the bandstand or the coolest dog on the dance floor, a predominant note expressed in these stories about mastering an instrument and daring to express yourself in front of an audience and see where it all might lead, is a note of appreciation and gratitude for the people who inspired and cheered you on and helped you out along the way. For a full account of my childhood fixation on the Dave Clark Five –

March 18, 2019: The Favourite Popsters of My Youth And for my own memories of a decidedly peripheral career in the music biz – July 8, 2022: Now Go and Do LIkewise

11 Comments

Barry Allan Wells

20/11/2023 09:12:22 am

Fifty-eight years ago on April 26, 1965, the Rolling Stones headlined a now-infamous show at Treasure Island Gardens, south of the 401. It was the first time the Stones rolled into Canada on an American tour, with four dates on Canadian soil: Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto and little ol’ London, Ontario ~ population 180,000.

Reply

Keith Nisbet

17/5/2024 02:13:57 pm

Wow. I was there. I remember the craziness. My first concert. 12 years old. So disappointed they only played for 15 minutes. I couldn't afford the trip to Toronto for the Beatles earlier but this one at the Treasure Island arena was a great replacement. Oh well, a bit of memorabilia. I also remember a fellow student from London Central, Paul Spurgeon, if memory serves me well, getting up on stage briefly and putting his arm around Bill Wyman before the dragged him offstage.

Reply

Mark Richardson

20/11/2023 10:26:16 am

Thanks, Herman:

Reply

Jim Ross

20/11/2023 10:32:24 am

Great fun! I was never a musician - but all of this is very familiar. Every high school had several bands, and one or two survived graduation. I spent my Friday nights schlepping, yes, Traynors up and down the stairs. It took two of us to heave a Hammond B3 upstairs onto the stage at 6:00 and down again at 1:00 AM. My other job was doing the lights and setting off my homemade pyrogizmos - In 2023, I can't use the B-word. Biggest takeaway - lower your eyelids and tilt your head back when reading a contract.

Reply

Jim chapman

20/11/2023 01:28:20 pm

Hi Herman: I am so pleased that you liked the book enough to write about it. It was, as you note, a labour of love, as well as a massive 3.5 year project no sane man would ever have undertaken. I apologize (again) for the small print in the book but with so much information to share it would have been the size of a coffee table (and not just a coffee-table book) had I used a "normal-sized" font. One light erratum: to the best of my knowledge, none of the Arkangels went to Beck- Kenn, Dave and I went to Central, and Al went to Beal, but that had no bearing on the creation nor development of the band. None of us were at high school enough to have laid much claim to being alumni anyway! I note you that did not reference the picture of Herman "Rock God" Goodden in the book, likely due to s surfeit of modesty. Many people seem to think it alone is worth the price of the volume, and is certainly the most memorable photo therein!!

Reply

Herman Goodden

21/11/2023 01:21:18 am

Thanks for the correction, Jim. I have tweaked/eliminated any reference to Beck so that the piece now achieves the sober and totally factual sheen that readers expect of any account of the 1960s music scene. HG

Reply

20/11/2023 01:58:22 pm

What an ab so lute ly marvelous review of such a wonderful "Book" Hermann. Of all the terrific words you `compiled' to describe the remarkable, countless events and memories I like "embiggened" the best.

Reply

Bill Myles

21/11/2023 01:42:42 am

Great R&R moments in London´s rock history; Willow Creek fired after a few nights of a gig at the Orange Shilleleigh (Lucan) - they had no clue that the Bobby McGee - Creedence stuff was what went home in bars. Alan Merkely of Nudge fame trimming his fake moustache bit by bit until by end of week gig (Port Dover) he resembled a blond Hitler. (Said moustache forced upon him by rest of band - drinking age 21, band ages around 17, Al´s nickname "Baby" in some circles). Sly & The Family Stone actually show up for a Wonderland gig, and only 1 1/2 hrs. late.! Procol do a sound check but do a "no pay no play" (London Arena?). The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown (God of Hellfire) enlists Thundermug as backing band when Vincen Crane and company quit on Canadian tour (home to roost atomicaly). Lights go out on stage between every song on Johnny Winter´s "Still alive and well" tour (so the detoxed/rehab Johnny could be medicated with whatever). A relation to Steven Goodden confettis a Hammond to the point that 30+ yrs. hence it was still falling out (Polymorfous Perverts at Victoria Pub) (Same night a future relative of Mr. G was lost, but found hiding behind his amp - the clue being the emanating bass-notes)? "Bonky" Peterson becomes member of" "Peterson? and Vanwinkle" (shared love of music and smokeables),

Reply

Gary Lundrigan

21/11/2023 01:47:19 pm

A terrible wonderful book (see D. N. E.) Reading the book made me feel both very young and very old at the same time. Thanks Jim. Good on you. Best G. R.

Reply

Daniel Mailer

22/11/2023 11:42:58 pm

Good one Herman, but then again they are all good.

Reply

Rev. Michael Prieur

22/11/2023 11:46:10 pm

I like how your Hermaneutics uses imagery in tandem with your commentary, which is never boring! God bless your fertile and ever-challenging mind!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed