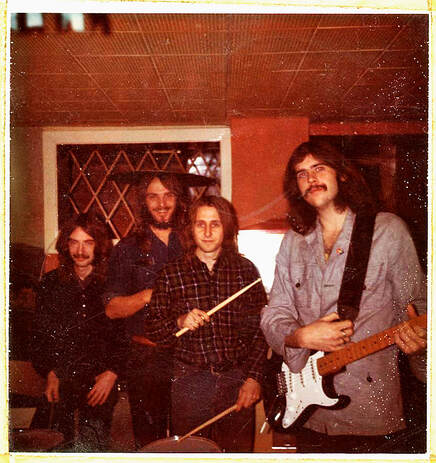

Four fifths of The Polymorphous Perverts on the morning after a Victoria Tavern gig, circa 1972 Four fifths of The Polymorphous Perverts on the morning after a Victoria Tavern gig, circa 1972 LONDON, ONTARIO – When my son bought his first drum set at the age of fourteen and learned how to navigate his way around that kit with pretty impressive finesse, it set off a lot of memories of my own percussive explorations at that very same age. The day we set up his drums in the darkest corner of the basement, I tuned them and showed him some of the rudiments and it was a golden father/son moment. Epiphanies between the male generations can come with considerable time lags. It can be twenty or thirty years until the kid realizes, “So that’s what Dad was talking about.” This was one of those wonderful occasions when I was able to give him the key to some arcane body of knowledge at the very moment he was burning to learn it. Then, like giving one last push as my son pedaled away on a bike with no training wheels, I stepped back to watch as youthful vitality and a love of music got melded together and the kid set off to see where it all might lead him. And here’s what most people don’t get if they’ve never taken part in making music: Even if the only place that dream ever takes you and your colleagues is into one another's basements on nights when the wives are out, there are sublime pleasures to be enjoyed in huddling around the companionable warmth of some old tube amplifiers and working up some tunes. The give and take of musical interplay brings a whole new dimension to friendships and your first-hand appreciation of what goes into making music at all well will deepen your appreciation of every concert you see and every record you play.

In no time at all, the kid started forming some pretty scrappy bands with friends who’d rehearse at each other’s houses. When it was our turn to host these foundation-rumbling struggle sessions, I marveled anew at my parents’ capacity for tolerating such an ungodly racket, though the floorboards in our small cottage are even thinner than at my parents’ house and we’ve never had a second storey (or accessible attic) to repair to in a bid to dampen the aural onslaught. Never a master of the triple flam paradiddle, I did attain the status of a competent basher. My son quite quickly became a far better drummer than I ever was and started playing his first gigs at house parties and high school talent shows. I attended the first of those school shows in Central’s auditorium where I silently willed him from one of the back rows to remember to breathe in his nervousness during their opening number. He was so pumped, it was scary. But once he got his bearings, he put that maximally primed tension to good use in a pretty impressive performance. Later on he was able to move things along to a quasi-professional level that I never attained and which must’ve been a lot of fun while it lasted. There was a ramshackle tour one summer that (not counting free beer) enriched nobody but if memory serves, paid for their van’s gas and included a gig or two out of province. And later on his band released one very limited edition self-produced record that was printed on remarkably heavy, embossed vinyl. So he’s got some souvenirs from his musical sojourn which he’ll cherish for the rest of his life. In his sixteenth year I was shopping with the kid for one of his Christmas presents – replacement skins for his two mounted tom-toms. And hanging around the counter of the music store as he talked measurements, features and specs with the all-knowing clerk, I watched a gaggle of boys come in and shake the snow from their hair as they excitedly ran upstairs to the guitar shop, talking about which amplifiers they wanted to try out first. And that was all it took to send me spinning down a time tunnel, landing in John Bellone’s music shop one Saturday afternoon in the winter of 1966 as me and three other grade nine twerps returned the speaker columns and microphones we’d rented for our very first party gig. When Mr. Bellone deigned to ask if our show went well, that somehow represented a greater validation of our musical dreams than anything from the night before. In fact, the concert had been a rather resounding disaster. Our bass player’s demented dog bit me in the leg as we hauled the last of our equipment out of the rehearsal room, which played havoc with my drum pedal dexterity for the night. We all hated singing and were far more comfortable grinding out instrumentals or Yardbirds covers – most notoriously, the profoundly tedious I’m a Man (Ha! we were fourteen year-old pups) – with just one or two quick verses and lots of instrumental noodling. Playing before an actual audience with rented amplifying equipment, we realized how excruciatingly bad even those minimal vocals were. On the liner notes to an early album, American guitar wizard Leo Kotke rather harshly compared his singing voice to “geese farts on a muggy day”. It’s a beautiful simile but the people who most reliably sing that way are adolescent boys in the grip of the pubic wars who suddenly have to contend with an unwieldy set of thickening vocal cords that crack and lurch half an octave out of key just when you were hoping to impress the girls. Later when my vocal cords settled down, I learned to pound out my pain on keyboards and guitar as well and concocted several dozen original songs – one or two of which I like to think were at least a wee bit clever – that were all built around the same six chords. Very occasionally we’d land a party gig or a spot on Bill Paul’s old cable TV show and for a few years the folks at the Victoria Tavern would let us play on a stage in their basement room on a Monday night in the Christmas season when we promised we’d pack out the joint with our friends. And I do look back with particular pride on the perfectly brilliant names we came up with for the latest iteration of our band . . . like the Polymorphous Perverts, Little Kenny & the Spit Ups, Tony & Chester Wong, Ernest Forepaw and the Premonitions, the Hi-Tones (we used that name for our only wedding gig at the request of the bride’s father) and Dunstan P. Schrapnell and the Screaming Heebie Jeebies. Some time this year – hopefully before the snow flies – we should see the release of the new book which my friend Jim Chapman (of Bluesmen Revue and Incontinentals fame) has been working on which will combine his own musical memoirs and what promises to be a pretty comprehensive survey of the bands that were working the London scene in the 1960s. Responding to my request for some preview information, Jim wrote: “The final tally was 192,000 words and 905 pictures, plus write-ups on every ‘established’ London and area band that played more than 20 gigs during the decade of the 60's. I believe the final total is 85. And as far as I can tell I have the name and instrument played of every member of every one of those bands, including players who came and went along the way. There are also sections about favourite teen dances, fashions, radio and TV shows, eateries, dance venues and much more. And there are a lot of anecdotes, many funny, some not, about my own life as a musician from 1955 to 2020.” Even though those provisos about ‘established’ and ‘twenty gigs’ rule out the inclusion of any Perverts or Spit-Ups lore, I await this book with giddy expectations. That local scene meant a lot to me while growing up and I was honoured when Jim asked me (and dozens of other Londoners) if we wanted to contribute a favourite memory from that time. And here is the story I sent along to him: In February of 1969 at the age of sixteen I quit school, thereby winning the opprobrium of all right thinking people (which I expected) and the majority of my friends as well (which I did not). My marks had actually been okay but I couldn’t have cared less about the subjects I was (ha ha) studying and was determined to clear the deck of distractions and really try my hand at more challenging pursuits – like visual art and writing – and see if anything took hold. I was so wired up just then to the so-called thinking of my peer group, that my excitement about the exploratory path I’d embarked upon was temporarily sandbagged by the near-universal disapproval that suddenly engulfed me. Had I just made the stupidest decision of my life? That miasma lifted quite magically on my first Friday night as an ex-student when I went along (with two friends who would still talk to me) to a nightclub with a psychedelically ponderous name. "Thee Image" was situated in a long room on the second floor of an old commercial building on the east side of Richmond Street at the foot of Carling. A local band I’d never heard of called The Village Guild were set up on a small riser in the northwestern corner of the room. This was probably one of their last gigs. A few months later lead singer, Joe DeAngelis, joined forces with Bill Durst, Jim Corbett and Eddie Pranskus to form my all-time favourite London band, Thundermug; and the Guild’s blistering lead guitarist, Roy Thompson, (brother of Sheila Curnoe) relocated to Vancouver where he soon morphed into a respected jazz player. I knew none of this deeper history, none of these connections, in February of 1969. I’d never set foot in a nightclub before; had never heard a professional rock band play in a more acoustically forgiving environment than a high school gym or a hockey arena; had never been constituent in a humid crush of bodies pressing round a stage where a pulsing throb is set off in the solar plexus by an amplified bass and drums. I wonder now, did Thee Image even have a liquor licence? If so, how did I get in? If not, how did they stay in business? But what I did have already was a really decent record collection, largely comprised of albums produced by the first three or four waves of the British invasion. And when the Guild proceeded to tear their way through a dazzling, note-perfect rendition of The Nazz Are Blue (side one, track two of The Yardbirds’ Over Under Sideways Down) I practically levitated with the empowering realization of what London boys could do when they honed their skills and gave their all to an artistic pursuit. The revelation couldn’t have been simpler or more direct. There were people operating in my hometown who knew how to call down and manipulate this kind of creative fire. Their example gave me all the permission I needed to roll up my sleeves and see what I could conjure up on my own. Even then I had no illusions that music was going to be my vehicle of choice. And, as I very soon discovered, it sure wasn’t going to be visual art. But that writing thing . . . that didn’t seem so hopeless.

2 Comments

SUE CASSAN

9/7/2022 06:05:41 am

Thank you for the heads up on Jim Chapman’s book. And thank you for the memories of your own and your son’s musical journey. It is wonderful to read about the way the spark of creativity sets fire to another life that will be devoted to the flame.

Reply

Bill Myles

18/7/2022 11:40:50 am

Thanks for an enjoyable remenicense! Lovely picture of those four young men. They only look slightly perverted. Having played with quite a few drummers (often in duo/trio formats) I´ve discovered a couple of things about drummers. #1 - I normaly get along best with them. #2 - Their feel and pondus are much more important than -technique and perfect meter ("It don´t mean a thing if it aint got that swing"). #3 - The biggest difference one can make in a band is to change drummers (the audiences would of course notice the change of a singer more).

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed