Penelope Fitzgerald Penelope Fitzgerald LONDON, ONTARIO – When visiting anybody’s house for the first time, I will often seize an opportunity to duck into whichever room features the most bookcases to scope out the sort of fare they have on hand. And I’ve long wished some publisher would bring out a large picture book featuring nothing but photographs of worthy people’s bookshelves; printed big enough that you could make out all the titles and authors. One of the more engrossing distractions which I’ve enjoyed during this Batflu lockdown when so many televised interviews and discussions are recorded in people’s homes – more often than not with a shelf or a case of books in behind them – has been to move right up to the screen and squint my eyes to scan their collections. Barack Obama, I must say, had one of the lamest and paltriest such backdrops I’ve yet seen, punctuated with way too many knick-knacks and ornaments and empty spaces. (I’m sorry but anybody whose bookshelves are not crammed to overflowing is not likely to have any sort of prognostications worth airing; they’re just not taking in enough points of view.) And one of the most enticing backdrops is author (most recently of The Strange Death of Europe and The Madness of Crowds), Douglas Murray’s. Not only am I intrigued by the sheer size of his collection but he’s usually sitting far enough in front of it that it’s hard to make much out.

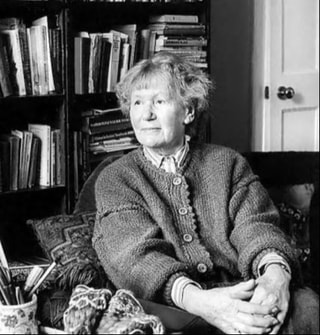

Last month when we hosted the most omnivorous reader I know for his annual three-day visit (a man who reads much more widely, deeply, eclectically and historically than I do) we spent about ten minutes discussing which volumes we’d been able to positively identify on Murray’s shelves. Between the two of us, we accounted for perhaps a quarter of what was on display. I think the only author we’d both twigged to was Michel Houllebecq. (“Well, of course, anybody diagnosing the cultural suicide of the West is going to have scads of Houllebecq,” we decided.) Primed by this suggestive discussion about other people’s literary enthusiasms, our guest then made a most unexpected inquiry: “Who have you read that I haven’t and should?” Woah. I was stymied for a few minutes. It was sort of like being buttonholed by Stephen Hawking at a party, wondering if you had any interesting theories about time. There was no writer of any serious vintage that I enjoyed who he was unlikely to know backwards and forwards already. And then remembering his general (but not absolute) aversion to reading anything published after 1960 (he disdains the binding employed in the production of their books at least as much as the callow cast of so many contemporary writers’ minds), I silently sorted through and quickly rejected a whole raft of more modern writers I enjoyed who didn’t seem likely to engage, let alone reward, attention as discriminating and specialized as his. And then it hit me: Penelope Fitzgerald (1916-2000) - a still too little-known novelist, biographer and essayist of startling range, originality and erudition who didn't really start producing books until she was a widow in her 60s with three grown up children. Despite winning some prestigious awards and generally positive reviews in her lifetime, Fitzgerald never really grabbed the literary spotlight and was frequently dismissed as a scatterbrained granny of little account. Call it the ‘Miss Marple effect.’ As Agatha Christie’s septuagenarian sleuth is able to slip into any sort of gathering because nobody thinks such a dotty old lady could be up to anything of any significance, so Penelope Fitzgerald operated quite happily underneath most people’s radar. Unfailingly thoughtful and incapable of generating soundbites on cue, she preferred being left to her own devices. She hated making a scene or a fuss about anything and was drawn to quiet souls, honest craftsmanship, honourable failures and misfits; to those who might never receive their due but wouldn’t dream of squawking about it. The English novelist, Sebastian Faulks, beautifully summed up the giddy sort of pleasure which her writing uniquely imparts: "Reading a Penelope Fitzgerald novel is like being taken for a ride in a peculiar kind of car. Everything is of top quality – the engine, the coachwork and the interior all fill you with confidence. Then, after a mile or so, someone throws the steering-wheel out of the window." Julian Barnes in a wonderful essay of appreciation called, The Deceptiveness of Penelope Fitzgerald affirms that quality in her narratives which gives the carefully contrived impression that things are slipping out of her control and extends it to the way that she presented herself as well: “Like her personal manner, her life and literary career seemed designed to wrong-foot, to turn attention away from the fact that she was, or would turn into a great novelist.” Admiring Fitzgerald greatly, Barnes recalls the occasion, just a few years before her death, when he appeared with her on a panel at some literary confab being held at York University, noting how “she comported herself as if she were some harmless jam-making grandmother who scarcely knew her way in the world . . . But the disguise wasn’t convincing since every so often, as if despite herself, her rare intelligence and instinctive wit would break through.” After a long day of pontificating on litra-chur, the two writers were driven to York station to travel back to London together. Barnes resumes his account: “When invited, I had been given the option of a modest fee and standard-class travel, or no fee and a first-class ticket. I had chosen the latter. The train drew in. I assumed that the university could not possibly have given an octogenarian of such literary distinction anything other than a first-class ticket. But when I set off towards what I assumed to be our carriage, I saw that she was heading in a more modest direction. Naturally, I joined her. I can’t remember what we talked about on the journey down . . . probably I asked the usual daft questions about what she was working on and when the next novel would appear. “At King’s Cross I suggested that we share a cab, since we both lived in the same part of north London. Oh no, she replied, she would take the Underground – after all she had been given this splendid free travel pass by the Mayor of London (she made it sound like a personal gift, rather than something every pensioner got). Assuming she must be feeling the day even longer than I did, I pressed again for the taxi option, but she was quietly obstinate, and came up with a clinching argument: she had to pick up a pint of milk on the way from the Underground station, and if she went home by cab it would mean having to go out again later. I ploddingly speculated that we could very easily stop the taxi outside the shop and have it wait while she bought her milk. ‘I hadn’t thought of that,’ she said. But no, I still hadn’t convinced her: she had decided to take the Underground and that was that. “So I waited beside her on the concourse while she looked for her free pass in the tumult of her carrier bag. It must be there, surely, but no, after much dredging, it didn’t seem to be findable. I was at this point feeling – and perhaps exhibiting – a certain impatience, so I marched us to the ticket machine, bought our tickets and squired her down the escalator to the Northern Line. As we waited for the train, she turned to me with an expression of gentle concern. ‘Oh dear,’ she said, ‘I do seem to have involved you in some low forms of transport.’ I was still laughing by the time I got home.” When Fitzgerald unexpectedly won the Booker Prize in 1979 for her third novel, Offshore, the condescension from media and academic circles was boundless. The book was dismissed in one press account as a “whimsical family drama” and the near-universal consensus was that it had been an “off year” for the Bookers. That her reputation flourishes more today - twenty years after her death - is attributable, I believe, to two gratifying developments. in 2013, Hermione Lee, one of the most popular biographers in the English-speaking world, published Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life, which laid out all of Fitzgerald's charm and comic elan in a heroic portrait of hardship stoically endured, a faith stubbornly maintained and an artistic vision single-handedly fulfilled. Then two years ago came the release of a pretty faithful film adaptation of her 1978 novel, The Bookshop, starring Emily Mortimer and Bill Nighy, And a popular movie always has a revivifying effect on a writer's back catalogue. None of Fitzgerald's nine novels clocks in at more than two hundred pages and all of them are available today in paperback editions with six of the most highly regarded titles collected in two sturdier volumes (with built-in ribbon bookmarks) of the Everyman’s Library of classics. . All of her writing is celebrated for its peerless evocation of time and place, her casually competent grasp of sometimes very arcane knowledge that she brings to the setting of any scene, and an all round narrative crispness that sometimes seems to border on sparsity. She never writes a syllable more than necessary to put across her stories and thereby manages to double their impact. There is a sublime artistic logic at work here. Which touches and haunts you more? The snatch of a beguiling song heard in passing? Or the big brassy show-stopper of a tune that gets reprised just before the final curtain? (If the latter, Fitzgerald is not the writer for you.) Because you know she isn’t going to waste a word, you have to attend smartly and play your part in each tale’s unfolding, and this deepens the reading experience. Throughout her oeuvre she faces square-on the manifestly evident facts that life does not come with a safety net and most people will endure a good deal of hardship in their sojourn through this world; facts she was able to take in her stride, not just because of her serene faith that this is not the only world we shall know, but also because she believed that finding a way to make it through with your honour and dignity intact were hallmarks of a life well lived. In an essay about how she transformed life experiences in her writing, Fitzgerald wrote, “A few years ago we were living on a Thames barge, and on the boat next door lived an elegant young male model. He saw that I was rather down in the dumps, a middle aged woman shabbily dressed and tired, and he took me on a day out to the sea, to Brighton. We went on all the rides and played all the slot machines. We walked for a while on the beach, then caught an open-top bus along the front. What happiness! A few days later he went back to Brighton, by himself, and walked into the sea until it had closed over his head and he drowned. But when I made him a character in one of my books, I couldn’t bear to let him kill himself. That would have meant that he had failed in life, whereas, really, his kindness made him the very symbol of success in my eyes.” In that same essay, she admitted, “I am drawn to people who seem to have been born defeated, or even profoundly lost. They are ready to assume the conditions that the world imposes on them, but they don’t manage to submit to them, despite their courage and their best efforts. They are not envious, simply compassless. When I write it is to give these people a voice." Nearly a decade later, shortly before her death, in an interview with Hermione Lee, she restated that commitment: “I have remained true to my deepest convictions – I mean to the courage of those who are born to be defeated, the weaknesses of the strong, and the tragedy of misunderstandings and missed opportunities which I have done my best to treat as comedy, for otherwise how can we manage to bear it?” The first Fitzgerald book I ever read was her brilliant and enchanting group biography of her father and three uncles, The Knox Brothers. Fitzgerald’s father was Edmund ‘Evoe’ Knox (the first-born and longest-lived of the brothers) a poet and editor of Punch when that weekly humour magazine achieved its largest circulation. Then there was Dillwyn, a man of immense scholarship and intuition and a crackerjack cryptographer who secretly worked for the British government during both World Wars, breaking the German flag-code in the First and shortening the search for a solution to Enigma in the Second. As their father was the Anglican bishop of Manchester, it is not too surprising that the two youngest brothers became clergymen though they both rejected as gently as possible their father’s evangelical propensities. Wilfrid at least stuck with the C of E whereas Ronald upset everyone by swimming the Tiber and writing dozens of books (including apologetics, detective novels, satire, literary and social criticism, a translation of the Old and New Testaments and a book of acrostics) becoming the best known English Catholic spokesman since Cardinal Newman. (Here is a Hermaneutics from December 2019 in which I fully explore the wonder of Penelope’s Uncle Ronald: The Inimitable Ronald Knox.) The Knox Brothers is a remarkable portrait of the family from which she was descended, notable for its brevity and wit (of course) but also for the generous understanding and pity extended to every last one of its subjects. “All four brothers had keen intelligences and tender and affectionate hearts,” Fitzgerald wrote. “This made the tensions between their common background and their divergent beliefs and careers all the more poignant.” Until reading Hermione Lee’s biography, I’d blandly assumed that with the Knox family in her background, Fitzgerald must have lived a fairly comfortable, even cushy life. While her childhood was indeed charmed and bountiful and she went on to earn a first class honours degree in English at Oxford's Somerville College (where C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien were among her tutors) the degree to which she fell through the cracks as an adult is shocking to behold. In 1941 Penelope married Desmond Fitzgerald, MC, a dashing Irish Catholic who had a very eventful military career in World War II, the horrors of which permanently broke his nerves and weakened his character, eventually driving him to slow ruination by drink. In her biography of Fitzgerald, Lee includes a daffy anecdote which tells how the Fitzgeralds accommodated the disparity of cult in their home, quoting a family friend who remembered driving Penelope (who she always called ‘Mops’) and her son Valpy to a dental appointment: “Mops said to him, ‘Now, darling, the dentist is going to ask whether you’ve worn your plate all along. Don’t answer, because you’ve just been to confession, and I don’t want you to tell a lie. I will say, yes.’ Her own scruples involved sticking consistently to the bargain she had made in marrying a Catholic: she sent the children off to Mass every Sunday, while she went to her own Anglican service. On trips abroad with Valpy, though, she would happily go to Catholic Mass with him.” Throughout the war years Penelope worked as a programme assistant at the BBC (inspiration for her 1980 novel, Human Voices) and for two years in the early 50s she and Desmond edited and published a political-cum-literary journal called World Review which never really got off the ground despite the fact that they were able to run poems and articles and stories by such heavy hitters as Dylan Thomas, Jean Paul Sartre and J.D. Salinger. It is possible to imagine how very differently Penelope's career might have played out with a bit of luck. But luck was not to be had. They hit the wall financially, couldn't raise emergency funds and with the collapse of World Review, the dissolution of Desmond now raced along with a vengeance. When Desmond was at his lowest dysfunctional ebb, husband and wife lived apart for stretches at a time when the raising of the children, the earning of a living with various teaching and tutoring gigs, were all left up to Penelope. During the most chronic period of the couple’s estrangement, Fitzgerald and her three children subsisted in a leaky houseboat that eventually sank, taking with it all of her books and manuscripts and files. From there she moved into dispiriting public housing for more than a decade where Desmond eventually rejoined her and was able to hold down menial work and contribute something to their upkeep. Though never dealt with in a rancorous or resentful way, the apparent unsuitability of the people we fall in love with is a common enough theme in Fitzgerald’s fiction. In one of her later novels, The Gate of Angels (1990), Fitzgerald goes so far as to ask “whether men and women are ever quite the right thing for each other.” Yet in neither fiction nor life did Fitzgerald entertain packing it in as an honourable solution to an ill-fitting union. There are no great and starry-eyed victories for Fitzgerald’s fictional couples but they do often discern the wisdom of that most commonly repeated phrase in the I Ching: “Perseverance furthers”. Chiara and Salvatore, the young embattled couple in her 1986 novel Innocence, barely resist splitting up before finding a new hold that seems to promise they might be able to forge a future after all. In a kind of shattered relief to have made it through their latest ordeal, Salvatore throws up his hands and asks, “What’s to become of us? We can’t go on like this.” “Yes, we can go on like this,” Chiara answers him. “We can go on exactly like this for the rest of our lives.” Penelope never coddled her husband and, she sometimes kept him at bay but neither did she ever desert him, dump him or betray him and in the last considerable stretch of his life they even managed to live together again and prop each other up in what appears to have been a reasonable semblance of a marriage. Penelope wrote and published a very obscure study of the pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones in the year before Desmond died and during his final illness, she tried her hand at fiction, writing the kind of comic mystery that Desmond enjoyed, The Golden Child (1977), about the 1922 Tutankhamen exhibition at the British Museum. In this story the lighting is kept dim at the Museum, not to protect the integrity of the historical artifacts but to disguise the fact that the entire exhibition is built around a fake corpse. Following the death of Desmond in 1976, the now-retired Penelope took turns living in the homes of her two grown daughters and their families and over the course of the next nineteen years published her memoir of her father and uncles, a biography of the now all but forgotten poet Charlotte Mew and the nine novels on which her reputation chiefly rests. Finally able to give her undivided attention to her writing at a time in life when most other writers are starting to wind down, she was able to produce an astonishing body of work that only increased in scope and ambition and invention as she went along. Her final novel from 1995, The Blue Flower - an exploration of the early life of the 18th century German Romantic poet Fritz von Hardenburg, later known as Novalis - is widely regarded as her masterpiece. Fitzgerald continued her quietly circumspect ways until the very end. One of her sons-in-law, the poet and translator Terence Dooley, has edited two posthumous volumes of her writings. First in 2003 appeared The Afterlife, one of my most treasured collections of miscellaneous essays on books, writers and visual artists if only because so many of her subjects are not the usual suspects (who else at that time was singing the praises of such neglected scribes as Mrs. Oliphant, Walter de la Mare, E.M. Delafield, Stevie Smith and J.L. Carr?) and her fascination with these fast-fading subjects is contagious. Then in 2008 Dooley produced, So I Have Thought of You, The Letters of Penelope Fitzgerald, which goes a considerable way to comprising the autobiography which Fitzgerald never had the time, the ego or the temperament to write. In a generous introduction to that volume, Dooley expresses what a privilege it was for him to live in such close proximity to a genius: "No woman is a hero to her son-in-law, and yet, when I first came across The Bookshop (til then unaware of its very existence) lying in bound-proof form on her kitchen table, where it had been written, and took advantage of Penelope’s temporary absence to read it in one sitting, I did have a sense of ‘What? And in our house?’ I had no doubt that this was the real thing, and still feel grateful for the stolen privilege of being one of the first people to read it. Ever after that Penelope had an extra dimension of mystery to me. I immediately wrote her a note to express my amazed and delighted appreciation; it would have been too embarrassing to confess in person. I was touched, much later, to come across the never-referred-to note among her papers in Texas.”

4 Comments

SUE CASSAN

6/7/2020 11:27:27 am

I still treasure the opportunity to read her that I owe to you, Herman, for introducing her to me. She was a marvel .

Reply

Max Lucchesi

7/7/2020 09:12:47 am

Oh Herman, why must you soil an otherwise truly worthy essay about a lovely old lady with your sniping, (the Obama crack) if you wanted to include the paucity of a person's library why not your hero Trump's. Again with the 'Cultural Sucicide of Europe' and the inclusion of two Islamophobes. Murray's book ' The Strange Death of Europe' was written when his pal Boris was on a Brexit wave forecasting the break up of the EU. Europe seems to have the virus under control while here in England we have the highest death rate in Europe and it's still rising. Let's not talk about Trump's criminal mismanagement. From Boris' vision of a 'Global Britain' with it's Singapore on Thames, reality is forcing Boris to adopt FDR's vision of a 'Dig for Britain' New Deal. Michel Houellebecq nee Thomas (pas un nome Francais) has a view of masculinity I assume is based on the one sided relationship Satre had with the far more intelligent Simone de Beauvoire who, as a dutiful French woman, sat back allowing her lover to shine. French Like Western men are still coming to terms with modern independent women. Yes she was a wonderful author, scion of a gifted family whose generosity of spirit and pity for the less fortunate shone through their actions and writings. A generosity and pity you seem to hoard and ration out to those you approve of, no matter how undeserving they are. That's not how virtue works.

Reply

David Warren

8/7/2020 04:53:14 pm

Just now read your essay on Penelope Fitzgerald, & struck by a coincidence

Reply

Max Lucchesi

9/7/2020 12:54:42 am

Dear Mr. Warren. I graciously accept your assessment of me as a compliment and am flattered that you wish to correct my spelling mistakes. I am puzzled however as to how my compressed soul leads to spelling mistakes in the first place. No doubt I am not Catholic enough to understand the connection. I obviously spent too much time with Jesuits during the 70s while working in Colombia and Ecuador to have an objective view of your Catholicism and politics.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed