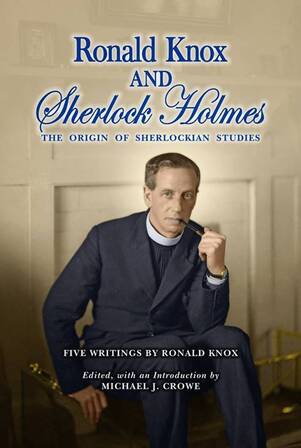

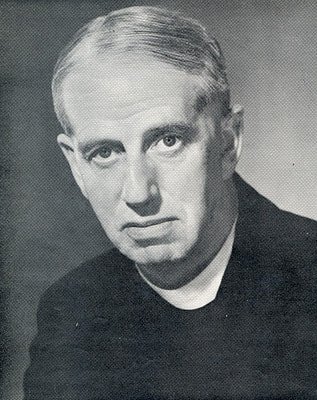

Ronald Knox (1888–1957) Ronald Knox (1888–1957) LONDON, ONTARIO – At this month’s meeting of the Wrinklings, the membership was asked to bring along and talk about those treasured religious texts – be they prayer books, missals, sermons, catechisms, encyclicals, biographies, memoirs, spiritual reflections, theological compendiums or anthologies – which have provided them with the most nourishment and direction over the years. Of the eight members who turned out on that last Wednesday night in November, I was astonished and heartened to see that three of us (yes, I was one) cited the sermons of Ronald Knox. The foremost English Catholic spokesman from the 1920s until his death, the scholar/priest Ronald Arbuthnott Knox (1888–1957) is not exactly a household name today. The youngest child of the Anglican bishop of Manchester, 'Ronnie' Knox (as many friends knew him even into adulthood) seemed always to be thinking, reading and reflecting. Asked at the age of four what he liked to do, he answered, "I think all day and at night, I think about the past." It seems a wonderfully funny answer until you learn that earlier that year, his mother had died and even though there wasn't that much of it yet to go burrowing through, the past did indeed hold powerfully wrenching attractions for the poor little gaffer. Acquainted with grief from an early age and humble and shy by nature, he nonetheless sported a cheerful and genial disposition all of his life. And when his father remarried a couple of years later, he married wisely and well; choosing a goodhearted stepmother for his children who never tried to take charge or take over and therefore triggered none of the traumas in her inherited brood that drive the plots of so many fairy tales. Knox was educated at Eton and had already published a collection of light verse in English, Latin and Greek – Signa Severa – by the time he arrived at Oxford’s Balliol College. Not only a precociously accomplished writer of considerable dexterity, Knox was also cognizant of his call to clerical life from boyhood and was ordained an Anglican priest at the age of twenty-two. Always favoring the Anglo/Catholic wing of that church (which was trying enough for his more fundamentalist father) Knox pulled out all the stops seven years later and went over to Rome in 1917. His ordination as a Catholic priest followed two years later and for this his father never forgave him; cutting him out of his will. Like John Henry Newman seventy-four years before him, Knox enacted a painfully disruptive pilgrim’s progress as the age’s brightest, rising Anglican light who suddenly ‘poped out’, much to the outrage and profound disappointment of his family and all right-thinking members of society. Evelyn Waugh wrote in his superb biography of Knox that even as recently as 1919, (the year of Knox’s ordination as a Catholic priest) “The Church of England was the religion of a governing class which then ruled a great part of the world. Her roots spread deep and wide in the established order, holding it together and drawing strength from it. Her fortunes were the concern of statesmen and journalists.” For a sensitive, kind and affable soul like Knox who was always eager to please those he cared about, raising a stink about his religious denomination was anathema. He dreaded abandoning the church of his youth but realized he couldn’t live a lie any longer after watching his brother Wilfred’s ordination as an Anglican priest. “We had been brought up together, known one another at Oxford as brothers seldom do,” Knox recorded in his account of this religious transition, A Spiritual Aeneid. “It should have been an occasion of the most complete happiness to see him now . . . in the same church, at the same altar, where I had stood three years before in his presence. And then, suddenly, I saw the other side of the picture. If this doubt, the shadow of a scruple which had grown in my mind, were justifiable . . . then neither he nor I was a priest . . . the accessories to the service – the bright vestments, the fresh flowers, the mysterious candlelight, were all settings to a sham jewel; we had been trapped, deceived, betrayed, into thinking it was all worthwhile.” The Booker Prize-winning novelist, Penelope Fitzgerald (1916-2000), was Ronald Knox’s niece and though she never produced a full biography of him, she brings some wonderfully rich familial knowledge to her fascinating 1977 group biography of her father and three uncles, The Knox Brothers. Fitzgerald’s father was Edmund ‘Evoe’ Knox (1881-1971), the first-born and longest-lived of the brothers who was a poet and the editor of Punch when that weekly humour magazine achieved its largest circulation. Next came Dillwyn (1883-1943), a man of immense scholarship and intuition and a crackerjack cryptographer who secretly worked for the British government during both World Wars, breaking the German flag-code in the First and shortening the search for a solution to Enigma in the Second. Considering their father’s ecclesial example, it is not too surprising that the two youngest brothers became clergymen though they both rejected as gently as possible their father’s more evangelical propensities. Though Wilfred (1886-1950), who Fitzgerald identifies as "the dandy of the family," waited until he was almost thirty to join the Anglican priesthood, he stuck with the C of E until the end of his days. Fitzgerald succinctly pinpoints that ‘shadow of a scruple’ which ultimately drove her uncle to the Catholic Church: “Ronnie felt something like despair at the English genius for irreligion – the comfortable feeling that there is a good deal of truth in all religions, but not enough to affect personal conduct. This seemed to him the legacy of Protestantism. 'If you have a sloppy religion, you get a sloppy atheism.’ If truth existed, then there must be one truth and one only, handed down in an unbroken line; a truth about which theorizing is forbidden and speculation unnecessary.” With a real sense of pity for these men who'd meant so much to her, Fitzgerald notes that, “All four brothers had keen intelligences and tender and affectionate hearts. This made the tensions between their common background and their divergent beliefs and careers all the more poignant.” However there were a few compensations attending Knox's conversion which made it slightly less desolating than Newman's. Largely because of the intellectual respect which Newman had gradually won for the Church over the course of his long career, the English Catholic hierarchy was less isolated and more confident. Knox's bishops (unlike Newman's) didn't instinctively mistrust this newbie's motives and seek to hide him away in some darkened corner of a parish where he'd be unlikely to attract attention. Once he came aboard St. Peter's barque, the captains of that vessel had a much better idea of how to employ this new mate's unique talents and sent him everywhere as a keynote speaker and a director of conferences and retreats. Indeed, the Church was undergoing a bit of a boom circa 1911. Though not yet a Catholic himself, the popular writer G.K. Chesterton whipped off a saucy little quatrain to salute Knox's conversion; drawing attention to the extra sting to the established order which was entailed in that resonant last name: Mary of Holyrood may smile indeed, Knowing what grim historic shade it shocks To see wit, laughter and the Popish creed Cluster and sparkle in the name of Knox. Shortly after his ordination, Knox was appointed Catholic chaplain at Oxford University; a post he filled until the outbreak of World War II. Ministering to that young and inquisitive flock – cradle Catholics mostly who were now being bombarded with diverting philosophical fashions like positivism, atheism and communism – was a task which made full use of Knox’s strengths as a writer and speaker. Three fat volumes of collected sermons, adding up to some 1600 pages of instruction and counsel, were published in the half decade after Knox’s death. Pastoral Sermons and Occasional Sermons (which included his magnificent panegyrics for G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc) were both published in 1960 and a couple years later came University Sermons which included all of the weekly conferences he delivered at Oxford during the years of his chaplaincy and then as a guest homilist in the subsequent decades. In 1952 Evelyn Waugh wrote a review of an earlier sampling of the Oxford sermons in which he conveys some of their appealing quality and tone, noting that : “Monsignor Knox’s purpose in these sermons was not primarily to attract converts or to awaken the adolescent conscience. He speaks to young people who have grown up in Catholic homes and at Catholic schools and have, most of them, had little previous contact with unbelievers. His task is to equip them to meet arguments against the Faith which they have never heard before and to ensure that the simple dogmatic and philosophic instruction of their youth keeps pace with the Philosophy and History Schools which are mostly directed by unsympathetic minds . . . He is sharing his own difficulties – the fidgeting doubts that disturb the early hours of the light sleeper – and explaining how he allays them until dawn comes and with it the daily sacrifice that dispels them.” Waugh speculates that the young men in Knox’s flock were particularly susceptible "in those black moments when the enthusiasm of the rally has worn off, when the phrase ‘social justice’ seems estranged from the salvation of the soul . . . In what Monsignor Knox calls ‘the 4 a.m. mood’ a sense of futility creeps in, a suspicion that the Christian system does not really hang together, that there are flaws in the logic, and adroit shifting about between natural causes, revelation and authority, that there are too many unresolved contradictions. And there are some, perhaps many [including, I suspect a certain Evelyn Waugh], to whom it is nearly always 4 a.m. To this mood with its temptation to despair, Monsignor Knox talks with unfailing kindness and solace..”  Photo from his days as an Oxford chaplain Photo from his days as an Oxford chaplain At no point in his priestly career was the formidably prolific Knox ever tied to the distracting duties of managing a parish. This undoubtedly freed him to devote so much of his focus and his energy to his writing, publishing more than 60 books in his lifetime. There were, of course, lots of works of apologetics and collections of the sermons and papers that he gave at various conferences and retreats and even broadcast over the radio. Two of the most popular of these books were The Mass in Slow Motion (1948) and The Creed in Slow Motion (1949), in which he breaks down and deeply explores, prayer by prayer and line by line, precisely what is being spoken, enacted and signified every day in the liturgical rites of the Church. "To believe a thing, in any sense worth the name," he writes in The Creed in Slow Motion, "means something much more than merely not denying it. It means focusing your mind on it, letting it haunt your imagination, caring and caring desperately, whether it is true or not.". This intellectual capacity to dig down and meditate on a single phrase or word until it revealed its deepest meanings and suggestions, was something Knox shared with his cryptographer brother, Dillwyn. A lesser manifestation of this same gift was his lifelong facility for filling in daily crossword puzzles in record time. Indeed, if he found some puzzle a little too easy, he would only read the clues for 'across' and would then deduce the 'down' words by blind hunch. That he regarded this form of recreation as a slightly unworthy indulgence was evident every Lent when, scrounging around for a pleasure he could sacrifice for the duration, more often than not, he gave up crosswords. In 1924, this inveterate solver of puzzles turned the tables and produced A Book of Acrostics, in which a meaty essay on the history of these fiendishly tricky puzzles was followed up with one hundred doozers of his own devising. Would you care for a small sample of the kind of rarefied fare he came up with? Clue: "To hint what's to someone's discredit - Adam to Eve might have said it." Answer: "Insinuate". (Get it? If not, think homonymically: "in sin you ate'.) Also, from very early on, Knox possessed an aptitude for literary satire. His Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes (1911) was the first mock-academic critical treatment of the Holmes canon; the witty prototype of a scholarly game which continues to this day. Knox was born around the same time as the first Holmes stories were debuting in print and as a wee lad, he and his three older brothers adored the tales and sent along a presumptuous letter care of Arthur Conan Doyle's publisher (signing themselves as ‘The Sign of Four’) in which they pointed out certain narrative discrepancies and inconsistencies which they urged their favourite author to tidy up and fix. He was mercurially adept at shaping his insights into whatever kind of literary form would best serve his narrative purpose, no matter how humble, archaic or recherche. Consider this five-line verse he contributed to Langford Reed's The Complete Limerick Book; a shimmering doggerel gem which he entitled The Modernist's Prayer: O God, forasmuch as without Thee We are not enabled to doubt Thee, Help us all by Thy grace To convince the whole race It knows nothing whatever about Thee. Knox was also a dab hand at translating classical and spiritual texts, including Virgil's Aeneid, Thomas a Kempis’ The Imitation of Christ and the first English edition of Therese of Lisieux’s Autobiography of a Saint. In 1936 at the specific request of the bishops of England and Wales, Knox undertook what turned out to be nine years' work in producing a contemporary English Catholic translation of the Holy Bible taken afresh from the Latin Vulgate version of the canonical scriptures which had been compiled by St. Jerome in the fourth century. As his watchword in this task, Knox took Hilaire Belloc's advice that "The business of a translator is not to ask, 'How shall I make this foreigner talk English?' but 'What would an Englishman have said to express this?'" Going into this project he realized full well (and quite correctly) that he was setting himself up for a wider barrage of criticism than he had ever aroused before: "If you translate, say, the Summa of St. Thomas, you expect to be cross-examined by people who understand philosophy and by people who understand Latin; but by no one else. If you translate the Bible, you are liable to be cross-examined by anybody; because everybody thinks he knows already what the Bible means." One of the most delightful books in the entire Knoxian canon is the monograph he wrote recounting this massive undertaking, On Englishing The Bible. "Words are not coins, dead things whose value can be mathematically computed," he writes. "Words are living things, full of shades of meaning, full of associations, and, what is more, they are apt to change their significance from one generation to the next. The translator who understands his job feels constantly, like Alice in Wonderland trying to play croquet with flamingos for mallets and hedgehogs for balls; words are forever eluding his grasp." Knox worked for even longer – sporadically as opposed to flat out – in compiling the staggeringly erudite Enthusiasm: A Chapter in The History of Religion (1950) which chronicles the manifold ways in which dozens of different Protestant sects developed and broke away from the Catholic Church. Evelyn Waugh noted that over the course of thirty years' compiling and shaping this pet project of a book, "[Knox's] ever-growing charity tempered his judgement." And in his introduction to Enthusiasm, Knox admitted how complicated and protracted his labours became in whipping this rather obsessional opus into shape: "There is a kind of book about which you may say, almost without exaggeration, that it is the whole of a man's literary life, the unique child of his thought. Other writings he may have published . . . it was all beside the mark. The Book was what mattered - he had lived with it all these years . . . Did he find himself in a library, he made straight for the shelves which promised light on one cherished subject; did he hit upon a telling quotation, a just metaphor, an adroit phrase, it was treasured up, in miser's fashion, for the Book . . . To be sure, when the plan of the Book was first conceived, all those years ago, it was to have been a broadside, a trumpet-blast, an end of controversy . . . Here, I would say, is what happens inevitably, if once the principle of Catholic unity is lost! All this confusion, this priggishness, this pedantry, this eccentricity and worse, follows directly from the rash step that takes you outside the fold of Peter! . . . But, somehow, in the writing my whole treatment of the subject became different; the more you got to know the men, the more human did they become." God and the Atom, published within weeks of the destruction of Hiroshima, grew out of a letter Knox wrote to The Times on August 19, 1945, in which he said, “If no word is to be spoken from any authoritative quarter, may I be allowed to express the idea which is (I suppose) simmering in most people’s minds? The idea, namely, that it would be a fine gesture if the Allied powers, having shown what the new bomb can do, cease to use it?” But as David Rooney observes in his rewarding literary biography of Knox, The Wine of Certitude (2009), "Geopolitics was not the focus of his reflections [in this book]. Rather, it was the effect on the individual person's way of thinking in the light of this new source of power. The splitting of the atom seemed to portend an encroachment on a forbidden frontier of science. The whole subatomic realm, which depended on statistical mechanics for its elucidation, seemed an affront to the traditional understanding of the common sense law of cause and effect." Indeed, it would not be too fanciful to say that this sober, 140-page book is a study of the intellectual and spiritual fallout that accrues when a shocking new development in physics coincidentally launches a detonating assault on the rightful province of metaphysics. And finally we turn to the idiosyncratic fiction and mysteries of Ronald Knox. In this realm where his narrative gifts were not so robust, he perches all alone on his own improbable branch as a very exotic bird indeed. More of an homage-paying mynah bird who picks up on the fetching notes of others, than an all-seeing eagle who maps out his own fresh terrain, Knox nonetheless came up with some delightfully elaborate baubles that are utterly unlike the products of any other writer. Barchester Pilgrimage (1936) is an inspired continuation of the six linked novels of Anglican clerical life and intrigue by Anthony Trollope - The Warden, Barchester Towers, Doctor Thorne, Framley Parsonage, The Small House at Allington and The Last Chronicle of Barset - which are collectively known as The Chronicles of Barsetshire. No critic had ever sung Barsetshire’s praises more insightfully than Knox. In 1958’s Literary Distractions, a posthumous collection of scattered essays, Knox ruminates for twenty-one pages on the everlasting attraction he felt for Trollope’s meticulously assembled world; an attraction no doubt given extra potency by his own nostalgia for the church in which he was raised and in which he'd played out the first years of his priesthood: And in this ingenious novel - the capstone of his admiration for all that Trollope had achieved - Knox brings the saga forward from the 1870s to the 1930s, lightly sketching out a series of sometimes wickedly funny vignettes that tell of the descendants of Trollope’s original characters who must contend with new forms of ecclesial erosion that their parents and grandparents never dreamt of; such as widespread agnosticism, the re-purposing of dis-used church properties and the community-dissolving acid of divorce. Some members of the Catholic hierarchy were distinctly un-amused to see the name of their foremost spokesman gracing the covers of gaudy-looking thrillers like The Three Taps, The Footsteps at the Lock, The Viaduct Murder and The Body in the Silo. Knox was writing his mysteries in the heyday of what aficionados call ‘The Golden Age’. His own books – and those of several of his contemporaries - should be regarded less as novels than as games or puzzles (and we know the regard he had for those) with their own strictly observed rules and conventions. Knox wrote murder mysteries not to understand how human passions could run so horribly amok, but to tease the brain. His mysteries are not so much who-dunnits - and they certainly aren't why-dunnits - so much as witty and oddly bloodless how-dunnits. Knox was a prominent member of The Detection Club; a convivial group of 20-some British mystery writers who gathered a few times a year to share dinner and talk shop. Included on the membership roll were some of the heaviest hitters of the day including Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, G.K. Chesterton, E.C. Bentley, Freeman Wills Croft, Anthony Berkeley, Margery Allingham, John Dickson Carr and Edmund Crispin. In his introduction to The Best Detective Stories of the Year 1928, Knox reproduced his tongue-in-cheek Decalogue, or Ten Commandments, for mystery writers which he had first developed for the members of The Detection Club. His list of prohibitions went like this: 1) The criminal must be someone mentioned in the early part of the story, but must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to follow. 2) All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course. 3) Not more than one secret room or passage is allowable. 4) No hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need a long scientific explanation at the end. 5) No Chinaman must figure in the story. [Allow me to head off any hyperventilating Social Justice Warriors at the pass. Ronald Knox was anything but a racist. Martin Edwards in The Golden Age of Murder (2015) explains the light-hearted thinking behind Commandment #5: Knox was “poking fun at thriller writers whose reliance on sinister Oriental villains had already become a racist cliché. The most famous culprit was Sax Rohmer (the exotic pseudonym of Birmingham-born Arthur Ward), creator of the villainous Fu Manchu, embodiment of ‘the Yellow Peril’.”] 6) No accident must ever help the detective, nor must he ever have an unaccountable intuition which proves to be right. 7) The detective himself must not commit the crime. 8) The detective must not light on any clues which are not instantly produced for the inspection of the reader. 9) The stupid friend of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal any thoughts which pass through his mind; his intelligence must be slightly, but very slightly, below that of the average reader. 10) Twin brothers, and doubles generally, must not appear unless we have been duly prepared for them. In a spirit that would have delighted Knox, Czech-Canadian author Josef Skvorecky produced a series of ten linked detective stories in 1988 called Sins for Father Knox in which he gleefully broke every one of the Monsignor’s commandments. And his fellow Detection Club member, Agatha Christie, regarded as the Queen of Crime more for her devilishly ingenious plotting than her often-plodding prose style, probably broke at least half of the Decalogue over the course of her career with Knox’s full-throated approval. Knox’s own favourite of all of his fictions was Let Dons Delight (1939), which gently and indulgently presents 350 years’ worth of overheard discussions in a Senior Common Room at a mythical Oxford college. Written as he was giving up his Oxford chaplaincy to devote himself to translating the Bible, Knox the scholar was reflecting on the considerable part that the university had played in his own formation and the history of Britain as well. Building each of the book's eight chapters around imagined conversations which take place at fifty-year intervals, Knox was able to capture the prevailing idiomatic styles of each period from 1588 to 1938, and also to chart the snowballing philosophical confusion of a preeminent school as it - sometimes incrementally and sometimes abruptly - became more and more cut loose from its original religious moorings when each college was managed by a different order of monks. The book’s continuity is provided by the unfailing cluelessness, the invincible wrongheadedness of succeeding generations of dons who believe they are upholding the noblest tutelary traditions as they are swept along in discombobulating currents which they neither perceive nor understand and therefore aren't even inclined to resist. The dons' complacency is regularly highlighted by their smug predictions of what lies ahead; ie: the Irish will never grow potatoes and the French will never revolt. The inverted French aphorism which Knox places on the title page translates as, "The more things stay the same, the more things change." It is skillfully chosen and impishly underlines the book's main premise: that it is unflagging commitment to a fixed creed and not the mere maintenance of physical and organizational forms, that will ultimately give coherence to any institution. Having situated himself along Catholicism’s ‘unbroken line’ by his 30th birthday, Knox never regarded himself as middle-aged, so much as medieval. This was a man who never drove or flew, never had a phone or went to the movies, and regarded the invention of the toast rack as the last great achievement of Western civilization. It was perfectly typical of Knox – with his wonderfully well-stocked mind and his perpetual delight in the archaic and the eccentric – that when he had a private audience with Pope Pius XII late in his life, he spent most of that precious half hour regaling the pontiff with tales about the Loch Ness Monster. The Pope kept asking the questions and, Knox being Knox, he couldn’t help but know a half dozen great whoppers about Nessie. Free of the leering apocalypse-mongering which curdles so much religious commentary, and never succumbing to the dry as dust hair-splitting too often favoured by theologians of more sober habits, I think what attracts three out of eight Wrinklings to the writing of Ronald Knox is its untrendy timelessness, the unfailingly gracious display of such profound depths of knowledge, and in virtually every situation where it would not be inapt, a winking openness to humour and mystery. Let me leave you with Evelyn Waugh’s touching account of Ronald Knox's final moments: “For three days he lay in a coma, but once Lady Eldon saw a stir of consciousness and asked whether he would like her to read to him from his own New Testament. He answered very faintly, but distinctly: ‘No’; and then after a long pause in which he seemed to have lapsed again into unconsciousness, there came from the death-bed, just audibly, in the idiom of his youth: ‘Awfully jolly of you to suggest it, though.’ "They were his last words.”

1 Comment

Max Lucchesi

4/12/2019 01:37:39 am

Brilliant essay on Knox. While the man himself has possibly become a footnote, his writings still influence Catholicism and Catholic education. But why no mention of his humorous and irreverent heresies? For example his reaction to the ease with which indulgences were granted by writing; " Surely God would grant him an indulgence for giving up his seat to an elderly lady". As to the one truth. While I am no theologian I have sat and meditated in 1000 year old churches, mosques and mandirs, they all have one thing in common, if one is prepared to accept it. That the faith, reverence and devotion of their worshipers is a living thing embedded within their walls. Even the Hindu religion with it's pantheon of deities says. "Bhagavaan ek hai. Lekin us lak pahuchane ke lie kaee sadekon ke saath hai". God is one but with many roads to reach him.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed