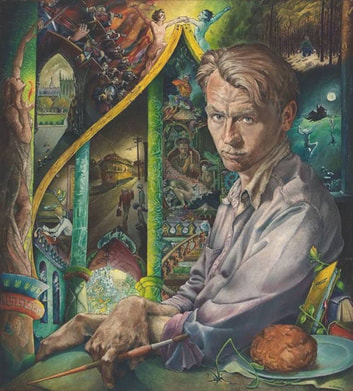

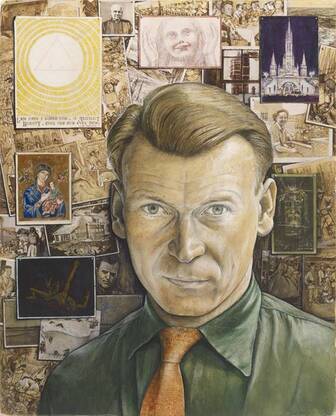

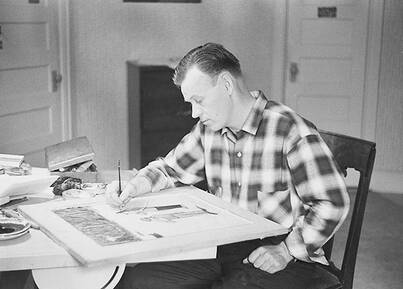

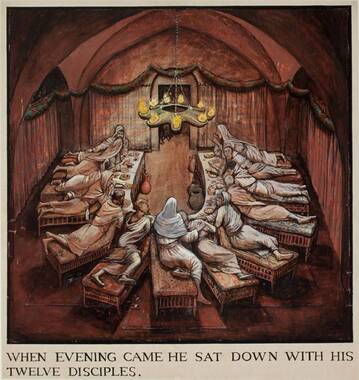

William Kurelek’s first self-portrait: The Romantic (1950) William Kurelek’s first self-portrait: The Romantic (1950) LONDON, ONTARIO – This excerpt from Three Artists: Kurelek, Chambers & Curnoe, examines the shocking critical neglect, punctuated by occasional notes of contempt, that William Kurelek (1927–77) endured at the hands of the Canadian art establishment. In the final decade of his life, the almost frighteningly prolific Kurelek was beloved by a broad cross-section of the Canadian public like no other artist of his time. Hosting two major exhibitions per year at his peak (exhibitions which commonly sold out in their entirety), Kurelek’s pronounced commercial success aroused suspicion and resentment among his more envious peers. And on top of that, this profoundly shy man came with so many quirks and edges – most overtly, a devout and forthright Catholic faith which was the primary engine of his life – that the poor man couldn’t schmooze to save his life. “I don’t think he had much to do with other artists,” his agent Avrom Isaacs of the Isaacs Gallery told me. “He just went along his own way. One thing that comes to mind is there was a show of Gordon Rayner’s one night and Bill and his wife Jean showed up to my amazement because Bill never came to openings. So I said to Bill, ‘Nice to see you. What are you doing here?’ And he said, ‘Well, my wife wanted to see what artists look like.’ Other than his own openings, of course, that was about the only time he appeared.” Repeatedly William Kurelek maintained that as hard a slog as his formative years were, he was grateful that he hadn’t won commercial success earlier in his life as its distractions might have thrown him off his true path. One wonders if critical approval might have posed the same threat to his integrity but perhaps luckily, he never had to contend with much of that at all. For most of his career Kurelek was considered ‘beyond the pale’ critically. He was predominantly a creature of the commercial and not the public gallery system and except for one travel grant awarded by the Canada Council in 1969 to study poverty in Hong Kong, South Africa and India (for a series of paintings and sketches that would illustrate a poem, Pacem in Terris, by Father Murray Abraham, a Canadian missionary in North India) Kurelek seems never to have partaken of public arts grants – that lifeline without which many of his best known colleagues would not have been able to keep their careers afloat. With his penchant for rural landscapes peopled by farmers and peasants and his insistence on delivering a censorious and none-too-subtle Christian message in many of his canvases, Kurelek came off as a bit of a square and a throwback. When best-selling books and prints and calendars featuring his work started to appear in the ‘70s (and sell like the proverbial hotcakes), it seemed he might even start to incur resentment and a bit of a backlash à la Norman Rockwell, but I expect his singular lack of slickness saved him here. Kurelek was so manifestly operating out of his own deepest impulses unsullied by commercial or trendy considerations that you simply couldn’t go after him as a phoney or a hack. You might personally find his work cloddish or embarrassing but you knew he meant every stroke of it. And then with the least bit of research into his life and career (referring either to his autobiography or the documentary film about him, The Maze, in both of which no secret is made of his horrific struggles with depression) you came up against the fact that this was a man who had suffered terribly to win his position as an artist. It would require a pretty monstrous arrogance to deny that Kurelek had earned a credibility that could not be assailed. It was easier to just ignore him. In the first edition of his Concise History of Canadian Painting (Oxford University Press, 1973), published just four years before his death when Kurelek had already imprinted himself on the Canadian consciousness in a way that no other living Canadian artist had, Ottawa-based art historian, curator and critic Dennis Reid did not so much as mention him. When the book was revised and expanded for a second edition in 1988, three paragraphs were worked into a new concluding chapter which included the line, “When he died [Kurelek] had the broadest public following of any contemporary artist in Canada.” If Reid’s book had been entitled, Canadian Artists I Happen to Like, the original oversight would have been excusable but for a supposed history of Canadian painting (however ‘concise’) to not even acknowledge the existence of the most popular and one of the most prolific artists of his time is . . . well . . . emblematic of my contention that most of the Canadian art cognoscenti would rather pretend that William Kurelek never existed. It would be hard to overstate the importance of the 2011/2012 touring show, William Kurelek: The Messenger, in fleshing out a more complete understanding of the artist. Prior to this show Kurelek was – simultaneously – one of the most popular and least comprehended of 20th century Canadian artists. Organized by Andrew Kear, Tobi Bruce and Mary Jo Hughes and exhibited at the three major Canadian galleries where they served as curators (respectively, the Winnipeg Art Gallery, the Art Gallery of Hamilton and the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria), The Messenger was not only the largest Kurelek retrospective ever mounted but it brought together for the first time all of the different streams in Kurelek’s art. Dubbed the ‘People’s Painter’ largely because of his commitment to figurative painting and because of the phenomenal appeal of his rural and country scenes peopled by immigrant farmers and children that were gathered into calendars and best-selling picture books (like A Prairie Boy’s Summer, A Prairie Boy’s Winter and Kurelek’s Canada) there was an immediacy of appeal, a common recognisability to Kurelek’s work that made it approachable by a far wider swath of the Canadian populace than most artists can ever hope to reach. But as his popularity increased to a greater and yet greater extent (and as often happens when that kind of mass appeal has been achieved) this remarkably multifaceted artist largely became known for only one (and that the least troubling and least challenging) aspect of his work – what most art critics would classify as ‘folk art’ even though it was far more accomplished than the work of most other artists so designated such as Grandma Moses or Maude Lewis. In addition to showing us the full range of his work, one of the gifts bequeathed to viewers of The Messenger in all of its boggling entirety is that we now bring new eyes to even what previously might have seemed the most unassuming of Kurelek’s pastoral paintings and can divine deeper and more ambivalent messages than we were previously equipped to see. By gathering together 85 paintings from every period of his career and presenting an unprecedentedly broad and complex monument of this artist’s accomplishments, The Messenger handily exploded the trite conception of William Kurelek as a simple folksy painter of prairie scenes. During his almost 20 years as an exhibiting artist, Kurelek knew that his prairie-scapes and farm scenes were the paintings with the broadest appeal and called them his “potboilers.” Though he felt a greater sense of urgency when working on his “didactic” paintings which imparted some kind of Christian lesson or warning, he was cannily persuaded by his Catholic confidant and friend Helen Cannon to keep both streams going. Not only did Cannon believe that Kurelek’s landscapes and farm scenes were imbued with more meaning because he believed in a Creator; she wanted to see him amass as many viewers and patrons as possible. “’Do both kinds of paintings,’ she urged me,” Kurelek writes in his autobiography. “’The others are just as important if you want a wide audience.’” And Kurelek made no bones about it, he wanted and he won as wide an audience as possible, both because it would validate his worth in his own eyes and his father’s and, most importantly, because he saw it as his special mission as a Christian to impart a moral lesson or message in his work. There was no standoffishness or feigned embarrassment on Kurelek’s part regarding his success; no nagging fear that he must be doing something wrong if his work spoke so powerfully to so many people; no nagging suspicion that his work might be more significant if its appeal was less obvious, its message more obscure.  Kurelek’s second self-portrait (1957) Kurelek’s second self-portrait (1957) With a total lifetime output of well over 2,000 paintings, this driven and almost frighteningly prolific artist also produced two self-portraits in 1950 and 1957 which act as bookends to his crucible-like years of geographic travel, psychiatric travail and religious questing and attainment. Both were included in The Messenger. The first, entitled Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, was executed just before he headed down to Mexico, and pays self-conscious homage to James Joyce’s novel about the need for the budding artist to jettison limiting cultural and theological trappings so as to finally encounter “the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.” Kurelek originally entitled it, The Romantic, he said, “because I represented myself as a dreamer: the Joycean artist about to burst into beautiful bloom, but not quite there yet.” This decidedly bohemian self-portrait – long tow-coloured hair draping across his brow, wearing a faded work shirt, open at the throat, and sleeves rolled up to the elbows – is set against a background of what he called an “imaginary temple” in which various painted devices (fancifully ornate columns, a window and a doorway, two wooden moulding strips bent together in the onion-shaped outline of an ogee arch) act as frames surrounding scenes of an orchestra playing, a man emerging from an egg, a young naked boy dancing in the moonlight. It is the portrait of an aspiring artist setting out on a quest of self-formation. In the second self-portrait, simply entitled, Self Portrait, a more confident but therefore more impervious Kurelek faces the viewer square on. His darker hair is combed off his brow. He wears a dark dress shirt buttoned to the neck and graced with an ochre-coloured tie, and is standing in front of a bulletin board entirely covered with souvenirs of his development such as family photographs and pictures of some of his earlier paintings but with the most prominent placement reserved for holy cards, a photograph of the English priest who helped him in his conversion to the Catholic faith and postcards of the Basilica at Lourdes and the imprint of Christ’s face on the Shroud of Turin. This is the portrait of an artist who has crossed continents and oceans and scrambled out to the crumbling outer rim of sanity and miraculously made it back again. He has encountered the ‘reality of experience’ and forged his own conscience in that harrowing process. This is a man who knows what he stands for and will not be shy about sharing what he has learned and what he believes with others. From this point on, one senses, all vanity burned away, he will not be susceptible to the siren call of false prophets. His head will not be turned. His heart will not be swayed. He has seen the light and found his path. The once-questing artist has indeed become the messenger. Even in the wake of that definitive exhibition, many critics still fail to recognize Kurelek’s accomplishments and achievement. Robert Enright (founding editor of the arts quarterly Border Crossings and a regular reviewer for both CBC Radio and The Globe & Mail) confessed when reviewing The Messenger in the fall of 2011 that he had hitherto missed the point about William Kurelek. Enright admitted that when he’d seen the previous major Kurelek retrospective in 1982 (Kurelek’s Vision of Canada, curated by Joan Murray for Oshawa’s Robert McLaughlin Gallery and comprising 48 paintings that were exhibited at 15 galleries across the country), he “judged him to be a minor folk painter concentrating on religious subjects, a kind of naive, flatland Bruegel.” This latest exhibition, Enright declared, “has fundamentally changed my mind about his achievement” so that he now sees him “as an artist of intense commitment and dedicated skill,” as well as one of “the most bizarre painters this country has produced . . . His work reads quite differently today than it did in the sixties, when he seemed a lone and curious figurative artist in an art world dominated by abstract painting. The open-ended plurality of current art making, and a postmodern tolerance for aesthetic and personal eccentricity make Kurelek more contemporary now than when he was alive. . . . In 2011, he seems like a Prairie Hieronymus Bosch, his naiveté replaced by a single-minded apocalyptic vision.”  Kurelek executing one of his table-top paintings Kurelek executing one of his table-top paintings So, from a “flatland Bruegel” to a “Prairie Hieronymus Bosch” – I guess that qualifies as a significant critical upgrade in some circles. In spite of Enright’s professed change of heart, it’s still hard not to sense some underlying animosity and condescension in play here. But then even Joan Murray (who curated the 1982 retrospective Enright cited above) wrote in the penultimate paragraph of her introduction to that exhibition’s catalogue: “By the time Kurelek died, at fifty, he had just barely improved as a painter. The table-top composition remained, but by 1975 he could achieve small miracles of colour and mood (as in Stooking). A big show of his landscape paintings teaches you to hate the finicky detail and ever-present green grass. In his work, in fact, there’s much to hate – an unformed sense of picture making, for instance.” I asked painter, author and Kurelek biographer Michael O’Brien if he could fathom this curator’s problem with ‘tabletop painting’. (And by the way, wouldn’t working on a flat surface rather than an upright one almost certainly contribute to his unique placement of the horizon line?) O’Brien told me, “What they don’t understand is that most of the art of Christendom until the advent of the Renaissance was tempera paints used in very thin layers and very liquid layers so it has to dry flat and it dries slowly. I paint the same way. I paint on a tabletop. I never use an evil ... an easel. Whoa, that’s a Freudian slip. I find there’s so much projection onto his life and it just reveals the lack of understanding on his critics’ part. It’s pathetic really.” Then, citing the impact of The Messenger as it criss-crossed the country, drawing record breaking crowds, O’Brien added, “There’s a whole new generation that really doesn’t know much about him. And people are staggered by this resurgence of interest in a phenomenal Canadian artist – a world artist – who lived among us. I think his reputation will just grow and grow from now on. He’s not going to go away.” I visited The Messenger at the Art Gallery of Hamilton on Good Friday of 2012, three weeks before the show was set to move on to Victoria and almost 35 years after the artist’s death. Any hopes I secretly harboured that the buzz may have died down and the crowds might have thinned out a little were utterly dashed by the fact that, quite unknown to me, the gallery had waived the admission fee for this holiday and holiest of days that held such supreme importance for Kurelek. The viewing rooms were packed with dozens upon dozens of enthusiastic viewers of all ages, many of them by dint of their attire and their noisy interaction with the paintings, giving off a decidedly non-cognoscenti aura. This press of humanity meant that for some of the more popular works, I had to wait for five or so minutes, bobbing my head this way or that as I worked my way to the front of the crowd to finally win a clear and unobstructed view which I in turn would soon have to relinquish out of courtesy for those who had now assembled behind me. But it also meant that I got to witness first hand Kurelek’s knack, undimmed by death, for reaching people of all sorts and conditions. And I was perfectly situated to hear a spontaneous two-word art review that I think would`ve thrilled the artist to the soles of his paint-spattered shoes.  William Kurelek: When Evening Came (1963) William Kurelek: When Evening Came (1963) A lot of the overtly religious works were displayed in one of the first rooms that visitors came to. I was originally scared off by the crowd in there and worked my way back to it a few hours later. While I was gazing upon Kurelek’s painting of the Last Supper, entitled When Evening Came (one of the works from The Passion of Christ series) my personal space was invaded by a man with Down’s syndrome, perhaps in his 30s, who was leading an older couple I presumed to be his parents to feast their eyeballs on it as well. I demurred as the woman apologised for the younger man`s exuberance and then I started to tear up as he tugged on her arm to draw her attention away from me and back to this wonderful painting of Christ and all of the Apostles meeting for the last time. “That’s today,” he announced to his parents, grinning with excitement and pride for having made this connection between life and art. “That’s today.”

3 Comments

Phi Bulani

9/11/2020 10:03:49 am

Herman! A thoroughly enjoyable read with morning coffee. What a pleasure, reminds of the last time I stood in front of a Kurelek!

Reply

Bill Craven

9/11/2020 12:24:18 pm

Interesting piece - 'William Kurelek and his Critics'. His last supper does not make all the apostles sit on one side of the table. Plus-plus.

Reply

Beth Stewart

21/12/2020 03:08:08 pm

Love Kurelek!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed