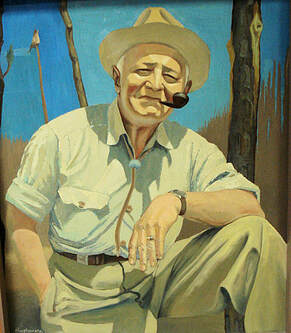

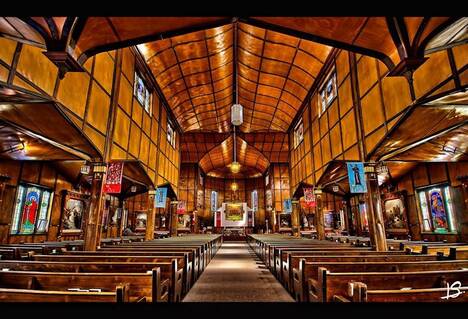

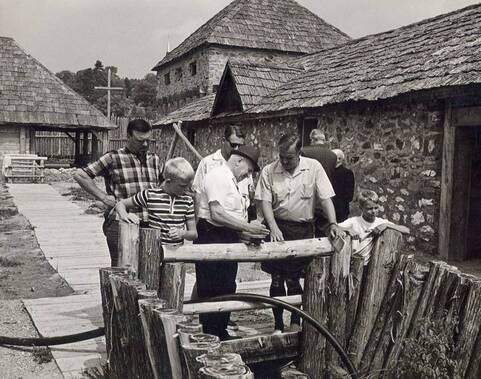

Wilf Jury (1890–1981) Wilf Jury (1890–1981) LONDON, ONTARIO – I was a little late twigging to the fact that I have been living all my life on richly storied and sacred ground. Like any child born into an even halfway decent home, I was suffused with that sense of enchantment that emanates from a loving mother and father (and, in my case, three usually goodhearted older brothers) and spills over into your first apprehensions of the larger world beyond the domestic realm. But by about the age of twelve, I started to feel that there were other kinds of nourishment and belonging that were inaccessible to me or any other denizen of the so-called ‘New World’ because our cultural roots just didn’t go deep enough. Canada just didn't have enough history. There were two strategies that helped me get past this existential disadvantage; this perception that I lived in a rather shallow backwater where nothing of any real importance had occurred. One was to join the famously ‘universal’ Roman Catholic Church which has an absolute genius for localizing the transcendent and plugging its members – wherever they might happen to live – into a two thousand year-old continuum whose significance outstrips any national affiliation going. And the other was to consider that even though my particular patch of turf may not have hosted any world renowned battles or revolutions - unlike some regions that have arguably suffered from altogether too much bloody history - no corner of the globe is bereft of remarkable stories and incidents if you’ll just roll up your sleeves and dig into the material that is closest to hand. For instance just outside of Midland, Ontario - a day’s drive from London - is the reconstructed Jesuit mission called Sainte-Marie among the Hurons where almost four hundred years ago the new and old worlds were brought face to face in a dramatic first encounter, both hopeful and tragic, that still has reverberations today. That we can visit that site today and learn so much about our deepest past is largely attributable to the work of Wilfrid Jury (1890-1981), an amateur London archaeologist who never let his lack of even an elementary school diploma hold him back from a lifetime of study and discovery. It was seeing Bruce Bereford’s superb 1991 adaptation of Brian Moore’s historical novel, Black Robe (1985) that first whetted my interest in Sainte-Marie among the Hurons. While that film has a few sequences that are almost too gruesome to watch, Moore’s novel has passages that are even more graphic and upsetting. Next turning to Francis Parkman’s 1894 book, The Jesuits in North America in the Seventeenth Century (the second volume in his definitive opus, France and England in North America) I found something even scarier than history-based fiction; a sober, totally factual account of the monstrous sufferings heroically borne by the Black Robes at the hands of their Iroquois torturers. Amazingly, this was all new material to me. As a mid-life convert to Catholicism, I attended the 'secular' school system (which at a time when the Lord's Prayer was recited each morning, meant 'Protestant') where the saga of Sainte-Marie among the Hurons was only studied for what it told us about the patterns of French settlement in the new world. Those brave Jesuit missionaries were regarded as nothing more inspiring than a sort of religiously eccentric wing of the Hudson’s Bay Company; as roving civil servants adept at the arts of colonization rather than courageous pioneers and martyrs who risked everything to plant the seed of faith in the new world. Naturally, we were spared the details of the Black Robes' horrific martyrdom. That would have been regarded as hysterical Catholic hagiography. That downplaying of the story's specifically Catholic elements was but a foretaste of the embarrassment that riddles nearly all of our schools today regarding any form of Christianity and our preachy post-modern shame about that whole era of European expansionism because, when you get right down to it, no culture is better than another and Western civilization is inherently toxic. Our family paid our first visit to Sainte-Marie among the Hurons in early October of 1996, marveling at the steadily brightening tint of the foliage - from a dullish weathered green to flaming yellow, orange and scarlet - as we traveled north that day. The original mission only operated from 1639-49; the merest of hiccups in the unrecorded, almost traceless stone age era which preceded and followed (for a while at least) that single decade. For those ten years about sixty Jesuits and lay French and twelve thousand Huron Indians (scattered throughout the region in bands) worked together to establish and maintain Sainte-Marie as the first inland European settlement in North America.  A reconstructed priest’s cell at Saint-Marie among the Hurons A reconstructed priest’s cell at Saint-Marie among the Hurons The Jesuits and Hurons had much to learn from one another and the reconstructed mission site with its couple dozen residential and public buildings is testament to their cultural cross-pollination. There’s a sophisticated series of locks – as ingeniously ornate as anything in Europe at the time – which provided fresh water for drinking and washing and also controlled the entry of canoes from the Wye River just outside the fortified walls. Teepees, longhouses and French style structures all made use of the same kind of bark for roofing material, either laid out in panels or cut into smaller overlapping shingles. With no hardware store just down the road, everything from hinges and door handles to bowls and gardening tools had to be custom made out of wood. The endlessly inventive dexterity of Sainte-Marie’s carpenters gives the whole settlement a kind of organic integrity which is marvelous to see and touch and smell. Survival was never an easy matter at Sainte-Marie but at least until the final year, the Jesuits and Hurons were able to maintain a fundamental agreement and trust with each other. The Jesuits, traveling out to Indian villages from their headquarters at Sainte-Marie, had converted about two thirds of the Huron tribe to Christianity. The generally pacifist Hurons already had more elaborate systems of agriculture and trade than most neighboring tribes, but improved those systems yet further and found a new measure of security in their alliance with the Black Robes. In all of the Jesuit missions throughout North America, one of the first tasks which the priests undertook was the compilation of a dictionary of each tribe's language; documents which have become historically invaluable.. Indeed the Jesuits recorded so much about the ways and customs of Indian life, that it is not uncommon in modern times for representatives of various tribes to check in with Church authorities when they want to reacquaint themselves with some of the finer details about how certain rituals and ceremonies were carried out. Today Jean de Brebeuf (1593-1649) who served a term as the Superior at Sainte-Marie, is the best known of the Black Robes who were stationed in Huronia . In 1640 he actually spent a fruitless year in the London region, working to convert the Neutrals. He had much better success at winning souls for Christ up north and also found the time to compile a grammar and history of the Huron language and translate Ladesma's Catechism from French into Huron. In 1641 Father Brebeuf unveiled a totally different kind of talent when he composed the very first - and many would still assert the finest - of all Canadian Christmas carols; setting his own original Huron lyrics about a very northern nativity to the melody of an old French folk song. In its English translation, The Huron Carol remains a staple of the Christmas choral repertoire today. But in the tenth year of the Black Robes' mission to Huronia, everything went drastically wrong. The Huron nation was being decimated from within and without. Unwittingly the Jesuits had brought along virulent European diseases – most particularly smallpox - for which the Hurons had no immunological defense. Many converted Hurons now mistrusted the Black Robes, convinced that in discarding their own spiritual traditions for Christianity, they had brought this plague of retribution upon themselves. The neighboring Iroquois, still ticked off with the Hurons for aiding French explorer Samuel de Champlain in raids against them forty years earlier, were retaliating with increasingly vicious attacks against Huron camps and ultimately Sainte-Marie itself. The bloody and horrific conclusion of this brief cross-cultural experiment is commemorated at the imposing Martyrs’ Shrine, a magnificent Catholic church which was built in 1926 on top of a hill just across the highway from Sainte-Marie. The names of the Jesuit missionaries and two lay helpers who were hideously tortured and killed – Jean de Brebeuf, Gabriel Lalemant, Antoine Daniel, Charles Garnier, Noel Chabanel, Isaac Jogues Rene Goupil and Jean de la Lane – are intoned there at every mass. On the day of our visit, a Catholic men’s choir from Germany happened to be touring the site and provided musical accompaniment for the mass which went down so well that they were persuaded to give an impromptu recital afterwards.  Interior of The Martyrs’ Shrine at Midland Interior of The Martyrs’ Shrine at Midland Much of the design and decoration inside this church reflects native motifs. The interior, gloriously paneled in warm blond cottonwood, is designed in the shape of a longhouse. Over the altar, the ceiling panels conform to the shape of an overturned canoe; an ingenious touch of symbolism suggesting the sanctuary a canoeist contrives when he’s caught in a storm by slipping underneath the protective shell. Such extensive use of wood throughout makes the church uniquely susceptible to fire but one wishes there was a less tacky safeguard against that danger than the metal racks of electric, coin-operated votive candles which twinkle away to the right of the altar. I was chuffed to learn during our first visit that my home parish of St. Peter's Cathedral in London donated the Stations of the Cross which line the walls of the Martyrs' Shrine. In addition to heading up the excavation and rebuilding of Sainte-Marie among the Hurons, Wilfrid Jury founded the Fanshawe Pioneer Village in northeast London and the UWO affiliated Ontario Museum of Archaeology. Wilf inherited his interest in the prehistory of our region from his father Amos (who lived to be 103) and started digging for Indian arrowheads and relics on the family farm just outside of London at the age of seven. In the 1920s and ‘30s Wilf and his dad regularly displayed their massive collection of relics at the Western Fair and always drew a good crowd. In 1973 the old Jury farmhouse was moved from Lobo and is now on permanent exhibition at the Fanshawe Pioneer Village. Entirely self-taught, Wilf knew his stuff and was brimming over with knowledge and insights that he loved sharing with others. But his passionate and intuitive approach in a rather specialized field sometimes gave (and continues to give) more fastidious historians the vapours, This was somewhat mitigated when he married Elsie McLeod Jury ((1910-93) in 1948. With her degrees in English, History and Library Science, she was a gifted researcher and loaned a patina of academic respectability to the many projects that she and Wilf worked on together. But it was Wilf's enthusiasm and drive, his attractively crusty demeanor and his genius for generating publicity and stirring up interest that drove their success and made so many of their projects come to fruition. Wilf’s work at Sainte-Marie came in two phases. From 1947 to 1952, he directed the excavation of the site which is chronicled in the book he coauthored with Elsie, Sainte-Marie among the Hurons (Oxford University Press, 1954). Then, in 1963, the government of Ontario guaranteed the funding for the careful reconstruction of the settlement and Wilf, working closely with the History Department of the University of Western Ontario in London, was back in business for five more years. In the winter of 1965, Wilf, then in his seventies, toured France, studying historic buildings of 17th century derivation. Wilf scrambled up into the rafters of one of these buildings to scope out the materials and techniques used in the roof joists and terrified his hosts who were sure he was going to kill himself. Wilf also visited the Vatican on that trip and had a special audience with Pope Paul VI with whom he talked about the great Midland project. He brought back some holy medals which the Pope had blessed and gave one to each of the workers on his crew along with a personal assurance that the Holy Father was appreciative of their work. Encountering a few rude interruptions before he could fully take up his vocation, Wilf’s life beautifully illustrates how an early disaster that scuppers all of your plans can cause you to alter your focus in a way that pays rich dividends later on. Wilf had enlisted in the British Navy at the outbreak of the First World War and was standing on the deck of a minesweeper in Halifax harbour on the morning of December 6, 1917, when three thousand tons of TNT in the hold of the cargo ship Mont Blanc suddenly detonated when that ship collided with a Belgian steamer. It was the biggest man-made explosion the world had ever seen until the dropping of the atom bomb on Hiroshima at the conclusion of the next World War,. The entire working class district of Halifax was leveled in one blow and 1,630 people were killed. Wilf was presumed to be among the dead – and his parents were so notified – but he eventually washed up on shore, unconscious but stubbornly alive. Slowly recovering from massive injuries, a badly weakened Wilf then succumbed to tuberculosis and had to spend the better part of the next seven years in the restrained regimen of sanitariums. It was at the Queen Alexandra Sanitarium in Byron, with time hanging heavy on his hands, that this most loosely affiliated of Baptists read his way through all seventy three volumes of the Jesuit Relations. These books gathered together the annual reports which Jesuit missionaries throughout North America dispatched to their superiors in France from 1632-72, and thus constitute the earliest North American histories we have. A large section of these writings concerned, of course, Sainte-Marie among the Hurons. Carefully annotated by Wilf, these Jesuit reports provided him with a remarkably rich and accurate blueprint for his life’s work in Indian archaeology.  Wilf Jury showing off his handiwork at Sainte-Marie Wilf Jury showing off his handiwork at Sainte-Marie I’ve always felt there’s a kind of cosmic symmetry at work here. Arcane religious documents provided Wilf with an invaluable overview of an obscure but pivotal period in our nation’s history. Armed with that information, Wilf was then able to turn around and develop the tragic three hundred year old story of those same scribes and their Huron allies into the kind of concrete terms that we can appreciate and learn from today. Now, forty years after Wilf Jury’s death, his work still bears ample fruit as scores of students, pilgrims and tourists pour through Sainte-Marie every day. During that 1996 visit, our family stayed at an inn about ten miles outside of Midland for two nights, devoting our first day to the Martyrs’ Shrine and the second day to Sainte-Marie. Our second night there we had dinner at the main building and as we walked back to our cabin in the fast-falling dusk, we took a detour to the west. The last orange and red traces of an early October sunset were bleeding into the frigid waters of the bay and flakes of snow were visible in the darkening air when we looked up toward the moon. Except for the inn behind us, everywhere we looked was rough, rocky land sprouting immense granite outcroppings and ink-black water rimmed by thick forest. We cast our minds back three and a half centuries and tried to imagine what it must have been like for a sophisticated and educated European cleric canoeing into this region for the very first time. There can be few less hospitable landscapes in all the world. The enormous loneliness of the land is still palpable in this modern, electric and vastly more populous age . . . but in 1640? And on top of that young priest's desolation and homesickness would be an unnerving uncertainty about the reception he'd be in for when he tried to bring the word of God to these mysterious strangers who shared few if any of his certainties and assumptions. Jean de Brebeuf, alone of the martyrs, was actually offered a reprieve. He first first came over as a missionary to Quebec and Huronia in 1626 and returned to France in 1629 for the final year of his religious formation while the British briefly held title to what had been known as New France. After some wretchedly difficult experiences during that first term of service, you might expect him to turn his energies to other fields where the harvest would be more promising or congenial. But on the contrary, Brebeuf eagerly returned to Huronia as soon as he could in 1634 and remained here until his martyrdom. The question which every awestruck visitor to Sainte-Marie asks is, “Where did the Black Robes find such courage?” And the answer can be found in this Instruction for those who are to be sent to work among the Hurons, which Brebeuf wrote for the Jesuit Relations of 1637: “Our real greatness is Jesus Christ. It is He alone and His Cross that you must seek in ministering to these peoples. If you take any other pathway here, you will find nothing but suffering of body and spirit; but if you have Christ and His Cross, you will have found the rose among the thorns, sweetness in the midst of bitterness, everything in nothingness.”

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed