LONDON, ONTARIO – Here’s an essay I wrote 29 summers ago: I stepped out our front door at one p.m. to sample the humours of the new day I’d risen to, when my five-year-old son came running up to me with an amazing bit of news. “Did you know old people bleed?” he asked. He’d been riding his bike on the sidewalk with his friend when they saw an old lady keel over and smash her face against some concrete steps across the road. “That’s her over there?” A neighbour lady across the way had taken the case in hand, had helped the old woman over to her porch and was applying a cold cloth to two grim-looking wounds; one on her right cheekbone and another just under her bottom lip. My neighbour came out to meet me, beyond the earshot of her patient. “She’s stewed to the gills,” she informed me. “She was weaving down the sidewalk when she started to lose her balance and made it all the way across that lawn before she finally fell over.”

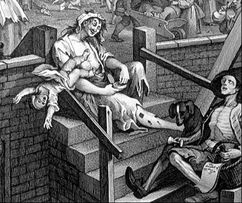

My neighbour told me where the old lady lived and asked if I’d be willing to escort her home. Of the two of us, I seemed the better-fitted for the job as my extra ballast would likely assist in the steady manipulation of one badly careening human. Women drunks are an uncommon sight on the streets of London. There must be a dozen male ‘regulars’ I see downtown, but a female sighting is comparatively rare and they never hit you up for spare change or try to make you listen to their interminable wall-eyed theories about the origins of the universe or political reform. I very much doubt that fewer women actually ‘take to drink’, but they’re quieter and more discreet about it and rarely exhibit the kind of obnoxious bluff and bluster that their male counterparts like to throw around. This old woman was frightened and ashamed and delivered a heartfelt apology for falling over in front of my son and his friend. “Those poor children,” she said, seeming to think she might’ve traumatized them. I couldn’t think of a gracious way to inform her that my son had been mightily impressed; that her tumble would nicely tide him over until his favourite wrestling show on Saturday afternoon. The smell of some kind of booze permeated the atmosphere around her like a humid halo. It was hard to place at first – not whiskey or rum or anything I’d ever willingly raised to my lips. It was more like . . . ah, but of course . . . the preferred poison of the serious female drinker – gin. This sad grey bird had been knocking back Pink Ladies since her favoured downtown watering hole had opened its door, had recklessly blown her cab fare on just one more drinky-poo and now had to navigate these addled streets entirely under her own power and control. A simple ten-block stretch it would’ve seemed back there in the bar when she rashly committed to the trek. ‘Sure, I’ll be fine. It’s just one foot in front of the other and steady as she goes.’ She wasn’t counting on that undulating sidewalk and the spilling of blood and the indignity of this all-too-public collapse; all these cow-eyed children and adults staring at her in her time of disgrace. She needed some reassurance before she’d let me walk her home. She was afraid I wanted to deliver her into the hands of the police or a hospital or that I would search out her children and tell them all about mother’s bad day. “I don’t know your name,” I consoled her. “I don’t know your children. I just want to help you get home.” With that, our compact was struck and we set out, navigating six short blocks in about 30 minutes, having to stop for rests whenever the world commenced spinning with particular vehemence and holding up traffic when it took us longer than the duration of one green light to make it across Wharncliffe Road. The danger of that single portage more than justified my services. On her own, in that condition, she would’ve had about as good a chance as a newborn puppy of making it to the other side. She talked more during the last couple of blocks, still expressing shame for her predicament, but admitting that there were some days when she just couldn’t help it; she couldn’t see the point in carrying on. I told her I felt that way some days too – which was trite of me and also a bit of a lie. She clearly meant there were days when she wished her life would end, and I don’t have those days. I certainly have days when I don’t see the point in carrying on but points aren’t that big a deal for me – I always want to carry on. “I feel so alone,” she told me. “Do you ever feel like that?” “No,” I had to tell her. “It’s pretty hard to feel that way with three kids in the house.” She couldn’t help smiling at that; a smile loaded with reminiscence and irony. She told me that she too used to yearn for the day when the kids would be grown and all moved out and she’d finally have some time to herself. She got her wish with a vengeance and now time to herself was the only kind of time she knew. We came to her boarding house and went inside and down a darkened hallway. I manipulated the key to the door of her tiny one-room cell where she poured her aching body onto the bed which filled about a third of her apartment. “Take care of yourself,” I said, setting the key on a chest of drawers and closing the door between us. A skinny cat in the hallway sidled up to me and began weaving itself between and around my ankles. Overhead a team of roofers hammered shingles onto blackened boards with nails – the perfect complement to a throbbing Thursday afternoon hangover. (London Free Press, 1989) What set me off in search of that column from 1989 were two far less involving midnight encounters with inebriates or stoners on consecutive nights last week while walking my dog. Is it just a coincidence that the moon was at its fullest last week? The first was a wiry, bearded man – maybe in his 30s – swearing and yelling as he jabbed some kind of needle into his arm. Eschewing the bench, he was sprawled on the pavement in that lookout point at the southeastern corner of the Kensington Bridge where we usually cut through on our way over to the river walk below the HMCS Prevost building. Clearly he was not a happy camper and doubtless was in need of all kinds of help but his snarly demeanour at that particular moment discouraged any inclination to offer assistance. Doubling down on this discouragement were Gracie’s ears which were pinned all the way back in a position of maximum alertness and dread and unmistakably telegraphed her preference for non-involvement: “Let’s just go around this fellow, okay? I don’t even want to sniff him and neither do you.” The next night’s inebriated drama took place a couple hundred feet to the north on the Queens Ave. Bridge where a young woman had clambered over the pedestrian guardrail with the stated intention of killing herself and now seemed to be entertaining second thoughts about the prospect of dropping into the Thames River. There were about a half dozen police cruisers and a couple of rescue vehicles from the Fire Department but except for one male and one female officer who were trying to reason with the hysterical woman and coax her back from her perch, the emergency personnel were mostly employed keeping vehicular and pedestrian traffic off the bridge. There had been a lot of rain in the preceding couple of days, so the river was not as parched as it recently had been. Nonetheless, the breaking of limbs struck me as a far more likely outcome than drowning if she ever had let go. When Gracie and I had worked our way back to the west side of the bridge about a half an hour later, the standoff continued much the same as before and as the cops were discouraging rubberneckers, we carried on home and trusted that things had worked out when we heard no reports of downtown suicides in the news next day. Part of what drew me to dig out that old column was – as goofy as I know this will sound - a kind of nostalgia for a time when public inebriates were more approachable. It’s not that I particularly enjoy hanging out with inarticulate and suffering strangers who’ve worked themselves into bad situations but I really hate having to walk by anybody who’s obviously hurting that bad and not extend a hand or a gesture or a word to help. Whether it grows out of my own fear of the violence and chaos that an inebriate projects or is enforced by the police who insist they’ve got this problem under control, avoidance of anyone in trouble dehumanizes me. IMAGE: William Hogarth: Gin Lane. Detail, etching and engraving on paper, 1751

2 Comments

Vince Cherniak

3/7/2018 09:41:49 pm

I liked that line, where she states she has no reason to go on, and you say that you don’t either, yet still you do go on. Or however it went.

Reply

Herman Goodden

3/7/2018 09:44:05 pm

He was an undeniably brilliant chap with an almost Joycean gift for wordplay usually marshalled in the service of not very articulate or self-aware characters. The humour is very dark and grim and one does develop an admiration for the pure Beckett type in all his maddening consistency and stubbornness. But I don't read him a lot and never pick him up with a lift in my heart. They're hardly alike but I feel the same way about Philp Roth's books. There's a genius at work in both cases but oh dear, it can be an ordeal. I am never tempted to rip my way through either of their oeuvres in a headlong binge for the sheer pleasure of their company.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed