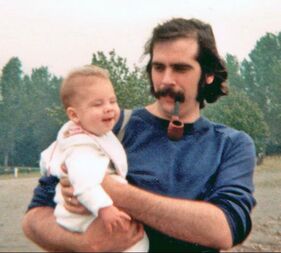

Port Bruce, 1981, 4 months into fatherhood Port Bruce, 1981, 4 months into fatherhood LONDON, ONTARIO – For a good few years now, I’ve wanted to write a Father’s Day essay focusing not on what magnificent, homage-worthy creatures dads are – though indeed many are and my own was not the least among them – but on the salutary effect that creating and helping to raise a crop of kids can have on a chap. Now that my work in this field of high honour would appear to be about 97.3% completed, I wish to review some of what I discovered and gratefully acknowledge what a thrilling and fulfilling adventure it has been to help prepare three worthy and lovable souls to make their way in the world. I was married at 25 and first became a parent at 28; my wife at 24 and 27. This seems late enough when you consider the sort of vigour and adaptability ideally required for each of those posts but, incredibly enough, in the quasi-bohemian circles in which we moved as aspiring artists, we were comparatively early adapters of the immemorial imperative to partner up and perpetuate the species. As boomers and superannuated hippies, my wife and I came of age in a time of so-called ‘sexual revolution’ when a lot of people, at least temporarily, affected to regard getting married or having kids as unnecessary and even retrograde propositions; as a kind of selling out or giving up; and as definite threats to the full flowering of one’s endlessly fascinating self.

While I was not indifferent to the libertine conceits of the age (in your 20s you still want to be perceived as somewhat cool, even if the people around you all seem to be talking rot), deep down I suspected that these claims had more to do with neurosis than personal freedom. Appealing as all that ‘free love’ hoo-ha might seem to a young male libido, my innermost temperament was stubbornly traditionalist and rejected the emerging sexual ethic of the Aquarian brotherhood. Considered in terms of popular music which in those days was the most reliable transmitter of our generation’s ideals, I was constitutionally more attuned to the down-to-earth realism of Ray Davies and The Kinks than, say, the posturing defiance of The Rolling Stones or the addled utopianism of The Jefferson Airplane. I never bought into the cornucopian myth of the Woodstock Nation which arrogantly proclaimed that we illuminated young ‘uns had definitively crossed over some socio-political threshold and outgrown our forbears’ need for committed marriages and a stable family life. Any misgivings I harboured for personal stodginess in not getting on board with the new order, quietly evaporated a few years later when most of the people who’d been touting its glories had second thoughts and decided that maybe they’d better get married after all. There were, however, some other institutions and social assumptions that I did stand four-square against. As a high school dropout, a non-driver and a fickle worker at any job that didn’t engage me at the deepest level (which in my teens and early 20’s was virtually every job that came my way) I was leery of getting ensnared by alliances and systems that would make unwanted demands on my time and energy, dragging me in directions I didn’t really wish to go. So why didn’t warning bells go off when my wife suddenly announced that it might be time for us to have some kids? Surely parenthood was just the kind of racket I’d so assiduously dodged in the past; requiring as it would (at the very least) a couple decades’ worth of steady commitment per child and the likely suspension of my long-shot hopes of ever making my living as a writer. During our first pregnancy, a not overly diplomatic friend of bookish inclinations called my attention to Cyril Connolly’s highly regarded essay, The Enemies of Promise, which posits “the pram in the hall” as the number one snuffer-out of artistic ambition. I dutifully read the piece and didn’t find Connolly’s argument very compelling, detecting in his tone a thin-blooded abstemiousness that frankly seemed too finicky and precious for this world. Casting about to see if Connolly made a more sustained or convincing case for his assertions anywhere else, I discovered that a handful of elegantly constructed and epigram-studded essays were pretty well all that he left behind. The man was a beautiful writer but even without the distraction of new life to care for (until his late 50s when this famous anti-parent absent-mindedly fathered a couple of afterthoughts of his own), the depressive, thrice-married and alcoholic Connolly was in fact a world-class procrastinator who never did produce the great work that so many people, including himself, once believed he would. Indeed, Connolly’s example suggested another way in which you could quite effectively extinguish your creative spark; that you could so completely clear your atmosphere of extraneous distractions and demands that you might also remove any contact-points of stimulation (or even irritation) that might inspire an artistic action or response. If you’ve really managed to arrange everything just the way you want it with no one demanding this or that, then maybe you won’t be impelled to produce anything much at all. Yes, I too was leery of getting swept up in schemes that weren’t my own but my wife was not some cause or system or racket looking for ways to enchain me and waste my time. She was the love of my life. I never felt more alive than when we were together and if she was ready to explore this uncanny power we had to create human beings out of pure thin air, then I was all for heading out onto the floor with her and taking a spin or three in the great regenerative dance of the universe. I had no such qualms about giving myself over when nothing less than the life force itself came calling. I often recall a day in spring around that time when we were sneaking up on the idea of having kids. We were mooching around on the river flats when our nosey dog’s pesterings persuaded a mallard hen to move her brood of fuzz-feathered chicks out of our path. Acting on an instinct that looked positively reckless, the mother drew her impossibly fragile-looking babies out into the open water where we feared the whole lot of them would come to grief. And we stared in slack-jawed awe as this tiny and vulnerable flock effortlessly latched onto a passing current and went bobbing away to safety in a sort of undulating flotilla. Both of our bellies went “whoosh” in that moment with a yearning recognition that we too were about to go spinning along in thrall to some primordial drive that would bear us away to where we needed to be, what we needed to become and what we needed to bring forth. One often hears from those who resent so-called “breeders” on strict ecological principles. Likening human beings to cancer is one of their lovelier touches. When these tin pot experts on what constitutes global health tire of haranguing us for imperiling their precious planet with our fecund exuberance, they sometimes aspire to be doctors of psychology instead, and tell us that having children is a fundamentally selfish act by which vainglorious people seek to replicate themselves and extend their fleeting existence on this earth by biological proxy. This too is seriously poisonous hooey. Perhaps there have been large-eared, chinless morons in certain over-bred royal lines who’ve entertained such self-perpetuating conceits but we never did. Even on my third tour of delivery room duty – every bit as shattering as the first – I stood there in my paper slippers and sweat-drenched hospital greens cradling this perfectly beautiful new creature whose seismic arrival I had just witnessed, and the only questions I felt impelled to ask this freshly hatched girl were, “Who are you?” and “Where did you come from?” Sure, there are some traits of, and certain likenesses to, yourselves and other members of your tribe that will sporadically appear in each of your kids but there are no carbon copies in the baby-producing biz. The closest it ever comes to replication is an occasional and only flickeringly apparent variation on a familial theme. Each child arrives as a whole new something under the sun with their very own character to unwrap and their very own destiny to work out. While neither parent really has a clue what they’re in for when their first child arrives, the mother at least has instincts and capacities that immediately kick in; and fortunately so, as the child is almost entirely mother-focussed for the first considerable stretch. Dads take a little longer to clue into their baby’s wavelength but can soon enough supplement their watery-kneed state of wonder by finding ways to pitch in and be a little more helpful. I did so by taking on some pointless full-time work that no longer seemed so pointless; happily shouldering a job I would’ve found wildly distracting and enervating only one year before, so as to provide a secure base for the family we were creating. And in one of the most surprising concomitant developments of them all, in that spare time which wasn’t as plentiful as it once had been, better marshalling of my energies meant that my literary aspirations didn’t go fallow either. Funnily enough, “the pram in the hall” (and a second in the vestibule and a third in the pantry) turned out not to be an impediment to writing at all but a very welcome and thoroughly rejuvenating spur. People call kids “hostages to fortune” because by their very existence, they demand that their parents get more involved in life so as to ensure a present and a future worth inhabiting. Quite literally, parents have “skin in the game” and are impelled to engage with the world in a more focused and determined way than ever before, developing new capacities and understandings within themselves as they bring along the next generation. Was it aggravating and maddening and just too bloody much sometimes? Of course. Any great project is. But there was nothing so negative in the fathering experience that it left any sort of mark or bruise worth mentioning; that depleted in any significant way the solemn privilege and sublime joy of getting to watch three new souls come into the fullness of being. So, thank you, kids, for finding your way into and utterly transforming our world. And please accept my heartiest wishes for a happy Father’s Day.

1 Comment

SUE CASSAN

16/6/2019 10:44:54 am

This is a most beautiful and heartfelt tribute to the enrichment that parenthood brings to an individual’s life. What greater spur and contributor to your or anyone’s life project than the responsibilities of providing for the physical and emotional needs of a new generation. How much more can a person see of the world when looking at it through the eyes of a young person, instead of being carried along in a closed carriage consisting of his or her contemporaries. What a wonderful skewering this is of nihilistic advocates of species suicide by failure to reproduce, and leaving the world empty of all the beauty and tragedy of human existence, occupied only by animal, vegetable and mineral. Kudos, congratulations and felicitations on your own Father’s Day celebration.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed