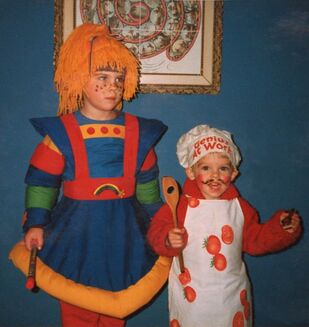

LONDON, ONTARIO - A good number of my favourite photographs in the world are pictures of our kids. This one here was snapped at about 5:30 p.m. on October 31st, 1986. On the left is our five year-old firstborn, kitted out in a meticulous, homemade recreation of the emblematic outfit worn by Rainbow Brite who (you may be excused for not remembering) was that year’s hottest cartoon craze for young girls. Preceding the snapping of this picture, my wife had overseen a week’s worth of fittings, tweakings and adjustments so as to get every detail correct. This doubtless explains the somewhat more pensive expression on our subject’s face. Yes, she knows it’s a magnificent costume but all those previews have somewhat worn away the mind-blowing revelation of it all. Now, let me call your attention to that ecstatic little maniac to her right. Literally six minutes before this particular Kodak moment was enshrined, our two year-old second-born was reconciled to the idea that he’d be staying home with his mom and his four month-old little sister while Rainbow Brite and I prowled the neighbourhood in search of refined carbohydrates in gaudy packaging. The rule we’d subscribed to until 5:24 p.m., was that you didn’t get to go out trick-or-treating until you were three. But when I saw him gazing at Rainbow Brite with a stoically wistful expression, I took my wife aside and said, “You know, he is two years and ten months which is practically three. Don’t you think we could rustle up some sort of . . . ?”

His older sister had worn almost the exact same outfit for her first Hallowe’en two years earlier so it was pretty easy to pull the components together again. That tiny apron was something the kids strapped on whenever they ‘helped’ their mom make pancakes. Once again we downsized my ‘Genius at Work’ chef’s hat with a circumference-reducing safety pin in the back and plucked a wooden spoon from the stove-side jar of utensils for the lad to brandish like a culinary scepter. The only new touch for his iteration of the costume was the Chef Boyardee-style moustache rendered with a water-soluble marker. And voila – just like that – he was good to go. What I find so moving about this photograph is the kid’s astonished delight to find himself participating in a previously withheld adventure – his moment has arrived, he’s in the game at last – the whole thing put across with a guileless enthusiasm which only a two year-old can exude. That look on a tiny chef’s face brings back memories of my own introduction to Hallowe’en which would’ve happened at about the same age. There is no photographic evidence of my trick-or-treating debut and I cannot recall what sort of get-up my mother concocted for me out of that trunk of outrageous cast-offs and accoutrements (some particularly ripe samples dating back to her own father’s childhood) which she ably and ingeniously curated throughout her children’s earliest years. But I vividly remember the thrill of accompanying my three older brothers out into the unaccustomed darkness of night and being swept along shadowy sidewalks that were positively teeming with similarly disguised people of every age and size. When I first read Huckleberry Finn and came upon that bit where Huck is out on some urgent mission in the middle of the night and notes that, “It even smelled dark,” it was the sensory overload which I experienced on my very first Hallowe’en that came roaring back to mind. In addition to being the great existential question of every developing kid as he strives to discern his destiny, “What are you going to be?” is the more immediately practical; question that kids throw around in the build-up to Hallowe’en. But for little people who haven’t been roaming the surface of this planet for very long and who labour each day to assemble a more perfect understanding of life and the world, it’s actually a little destabilizing to think of identity as fungible. And of course it isn’t just you who’s going through this shape-shifting metamorphosis. On this one particular night absolutely everybody’s getting in on the act. Little kids, like dogs and cats, can become notably anxious in situations where their loved ones can’t be readily discerned. I remember babysitting a dog once who knew me fairly well but when I emerged from the bathroom with a head of wet hair and wearing a robe, he squared off from me, growling, with the fur standing up on the back of his neck until I addressed him by name and told him to cool his jets. And for all the fun of scavenging sweets from strangers who magically opened up their homes to me, there was also something unsettling on my first Hallowe’en night in being swept along in a laughing army of bogus ghosts and hoboes and princesses and pirates who were plundering my neighbourhood. Though I continued to ply my Hallowe’en trade for about the next ten years, it (along with Valentine’s Day) began to stand out for me as a holiday that did not appreciably deepen or improve with age. By the time I was nine or ten, I knew that the householders chucking chocolate bars and bags of chips into the gaping maw of my pillowslip frankly wished I’d give it up. I’d ceased being adorable, my costumes were becoming lame, I was too embarrassed or taciturn to be any fun to interact with, and those householders quite correctly perceived that I was only using them to acquire a mountain of junk food that I was too cheap to buy for myself. I was twelve or thirteen when I gave up on Hallowe’en as a lost cause. (I know for sure that I never went out trick-or-treating by the time I reached high school.) Any spirit of fun or adventure had drained out of the day. The choosing of a costume had become this hopelessly fussy and neurotic ordeal. I was more interested in looking cool than wearing something fun. What a drag self-consciousness is in those first bleak years when it only seems to inhibit your every movement and gesture. I somehow got it into my head that any costume had to reflect some part of me, or subtly alter my nondescript image for the better. So that night I put on dark trousers and a shirt, donned a sort of cape from the costume trunk and inserted a twenty-five cent plastic dental appliance into my mouth which extended my canine teeth into a threatening pair of gnashers. “There we go,” I thought. “I’m the spitting image of Dracula.” This illusion shattered when I passed by a mirror and saw my reflection - which a real vampire would not - and had cause to remember that I was actually rather fat. And this dashing re-acquaintance with reality carried with it two further realizations: 1) I really didn’t need another mountain of chocolate bars and Cheetos. And 2) considering how his sustenance is derived, the only kind of vampire who could possibly seem cool (or at least tragically romantic) would have to be imperially slim and a notably reluctant diner; someone who’d only destroy another person’s life as a matter of survival and not because he felt a little peckish. A fat vampire was – ipso facto – an obscenity. And so I spat the plastic appliance from my mouth, folded up and put away the cape and bade Hallowe’en farewell for almost twenty years until I started to take out my own wee babies on their inaugural rounds. And by then I was a husband and a father and saw absolutely everything with new eyes. Of course, any parent takes a sense of time-travelling delight in introducing his kids to those special rituals he enjoyed as a child. We were living (and my wife and I still remain) in the same neighbourhood where my mother grew up (and where she and my father first began to court) and it was pleasing to think of five-year-old Verna Geraldine McQuiggan padding her way along these same leaf-strewn sidewalks in some fanciful get-up back in the 1920s. For all of its universality and commercial commodification, I’ve always appreciated the fact that Hallowe’en, at heart remains a do-it-yourself celebration that is rooted in specific neighbourhoods. And this sense was only deepened by that connection with my mom. And two and a half months after that little genius of a moustachioed chef was born, I joined the Roman Catholic Church and my faith was also informing how I now saw Hallowe’en. While I’ve always given a wide berth to the more graphic kinds of horror that turn up in more contemporary Hallowe’en stories and movies, I’ve always appreciated and even taken solace from a good spooky narrative that features some sort of interplay with the dead. And communicating with those who are no longer here is a big, big theme in the Catholic Church at this time of year. My insistence on spelling Hallowe’en in this archaic way is to emphasize that the word is a contraction for the ancient name of 'All Hallows’ Eve' (or 'evening') which begins at Vespers on the night before All Hallows or All Saints Day (on November 1st), which itself precedes All Souls Day (on November 2nd). Whether we’re venerating Heavenly saints or praying for the souls of the departed, all of these occasions (as well as Remembrance Day next Thursday) are commemorarations which cluster at the end of October and through most of November as Catholics observe the final holy days of the Church calendar preparatory to Advent and the great Festival of Christmas.

4 Comments

Darrell

4/11/2021 05:12:41 pm

I much enjoy reading your posts, Herm, and wonder if you've read any of Richard Ford's work .. methinks your writing styles are very similar..!!

Reply

Herman Goodden

5/11/2021 02:24:26 am

Interestingly enough, I haven't read any Ford yet but I've given away copies of his novels twice - one of them a fine fat compendium of his Sportswriter trilogy. It's kind of like I know he's really good and am saving him for my dotage

Reply

Max Lucchesi

5/11/2021 09:50:43 am

Herman, I have also been gazing at photos of my grand children currently 8000 miles to the east of me, in their costumes, before and after their trick or treat foray. From the large sack of goodies won, they are allowed 1 treat a day. In the England I grew up in, trick or treat came long after my childhood. Where I am at the moment, a small town in Italy, there is no Americana trick or treat or dressing up. There is quiet remembrance because on All Saints Day the whole family goes to Requiem Mass, then laden with flowers, go to spend the day with the generations of their family dead at the towns cemetery. Here they are " i morti" who are remembered, whose graves are tended and Requiem Masses said for.

Reply

Buddha Boy

5/11/2021 09:55:46 am

I suppose if I was a wholesaler or a retailer, I would embrace the crass commercialization of most of our annual holidays and significant cultural events.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed