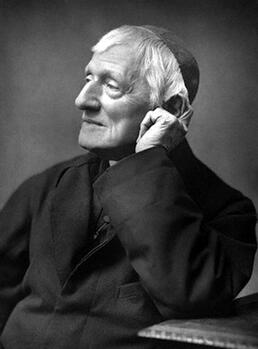

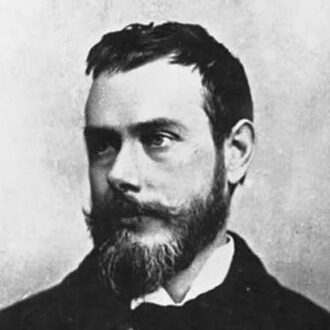

John Henry Newman (1801 - 1890) John Henry Newman (1801 - 1890) LONDON, ONTARIO – Cardinal John Henry Newman (1801–90) who was elevated to sainthood on Sunday, October 13, is widely regarded as one of the supreme prose stylists of the English language; a distinction which is avidly accorded him by temperaments as diverse as G.K. Chesterton and James Joyce. Less central to the reputation of this remarkably prodigious thinker and writer is the poetry he occasionally tossed off on the side. Newman had no illusions that his poetic gifts were of any accomplishment or significance. He took to poetry as nothing more than a form of recreation; a different modality in which to exercise his literary inclinations. Yet a representative anthology of Newman’s verse easily runs to 300 pages; not much less than a collected edition of the poems of another celebrated, 19th century, English Catholic writer who is remembered for nothing but his poetry, Francis Thompson (1850–1907). And with the distilling passage of 100 plus years since both men’s deaths, we find they are both primarily remembered for two poems apiece; a sprawling religious epic or ode which captured and still holds the public fancy and a humbler, more intimate verse which has also managed to endure. Beyond these similarities, we will be examining two dramatically dissimilar lives when we outline the careers of Newman and Thompson. Newman was born in a quietly desperate, middle-class Anglican family and rose to the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church. Thompson was born to well-heeled Catholic converts and almost died in the gutter. Prior to the 1840s, Newman was an Anglican vicar, an Oxford don and the leader of the ‘Tractarians’ or the ‘Oxford Movement’, a consortium of avid, young theologians who sought to shake off the provincialism of the established English Church and situate it more clearly within a broader and unbroken tradition dating back to the time of Christ and the desert fathers. Newman had already achieved esteem as the most eloquent and dynamic Anglican thinker of his generation. But unknown to anyone but his closest associates, for more than a decade Newman had been wracking his brains unto cognitive exhaustion, trying to make a case for the Church of England’s origins as anything nobler or more God-centred than a shell game which allowed Henry the VIII to shuck his barren wife and marry his pregnant mistress, He found it equally challenging to contort the chain of apostolic succession in such a way that it could be seen to connect St. Peter to any contemporary religious leader other than the current Catholic Pope. Realizing that his thought was leading him inexorably Rome-ward, Newman wrote to his sister in 1841, “I fear that I am clean dished.” Indeed this was no easy road which Newman courageously blazed. It had only been 60 years since English Catholics were allowed to openly practice their religion at all and their numbers were still miniscule. Most towns of any size had one glorious Anglican church (which had been stolen from the Catholics and refitted and repurposed), and one shabby near-Quonset hut of a Catholic chapel. To what use would such an impoverished and ragged remnant of a Church put a man of Newman’s rarefied gifts? In 1843 Newman resigned as Anglican Vicar of St. Mary’s, Oxford. He was also obliged to resign from his lecturing post at Oriel College, as Catholics were still barred from either attending or teaching at Oxford. His once-brilliant career was apparently ruined but in fact, it was the old status quo which now, ever-so-gradually, began to fall away. Having put behind him the energy-sapping, logic-wrenching compromises of his Anglican years, Newman was now free to commit his delicately-honed intelligence to that series of major works – The Idea of a University, Apologia Pro Vita Sua, The Grammar of Assent, An Essay on the Development of Doctrine – which comprise his lasting legacy to the world. The eight volumes of his Parochial and Plain Sermons, preached from the pulpit at St. Mary’s Oxford, are the only literary product of his Anglican years which still find wide purchase today. Newman’s anguished turning toward Rome proved to be the pivotal first stirring in what would shortly become a tidal wave of conversions. Unthinkable in 1845, a little more than a century later there were more practicing Catholics than Anglicans in England. Newman’s epic poem, The Dream of Gerontius, written in 1865 and inspired by the Requiem Offices, depicts the journey of a soul to God at the hour of his death. It was set to music by Sir Edward Elgar in 1900 and remains second only to Handel’s Messiah as the most popular English oratorio. A less daunting and much shorter poem, The Pillar of The Cloud, was written at sea in 1833 when Newman was returning from his first visit to Rome. His ship was becalmed in the Straits of Bonifacio and Newman was recovering from a dangerous bout of illness. A seed had been planted in his heart during that profoundly upsetting encounter with Catholic culture and Newman’s poem serves as an invocation, calling on God to help him through the trials of discernment and commitment which lay ahead: Lead, Kindly Light, amid the encircling gloom, Lead Thou me on! The Night is dark, and I am far from home – Lead Thou me on! Keep Thou my feet, I do not ask to see The distant scene, – one step enough for me. I was not ever thus, nor pray’d that Thou Shouldst lead me on, I loved to choose and see my path, but now Lead Thou me on! I loved the garish day, and, spite of fears, Pride ruled my will: remember not past years. So long Thy power hath blest me, sure it still Will lead me on, O’er moor and fen, o’er crag and torrent, till The night is gone; And with the morn those angel faces smile Which I have loved long since, and lost awhile.  Francis Thompson (1850 - 1907) Francis Thompson (1850 - 1907) AT THE OTHER END of the social spectrum, we find the poet Francis Thompson; a failed seminary student and a failed medical student who came down from Manchester and fell into opium addiction and vagabondage in the mean streets of London. Yet through all his dissipation, Thompson never lost his reverence for God and never ceased from prayer. The story of his first publication is the stuff of literary legend. From the depths of skid row, Thompson submitted some poems to Wilfrid Meynell, then the editor of the Catholic journal, Merry England. Having no return address, Thompson listed only the Charing Cross post office and after months of vain searching for the poet, Meynell published one of the poems as a means of calling him forth. And it worked. Wilfrid Meynell and his wife, the poet and essayist Alice Meynell, took the poet into their home and later worked out an arrangement where Thompson was also looked after by a nearby community of Franciscan monks for the rest of his short life. The epic poem for which Thompson is chiefly remembered (and which is included in every anthology of Catholic poetry) is The Hound of Heaven. This relentlessly rhythmic poem serves as an answer to Newman’s question in The Grammar of Assent: “The wicked flees, when no one pursueth, then why does he flee? whence his terror? Who is this that sees in solitude, in darkness, in the hidden chambers of his heart?” This ode also neatly deflates the pomposity of agnostics and certain dim seekers who speak about the arduous and one-sided search for God. As C.S. Lewis wryly observed, “As well speak about the mouse’s search for the cat.” His shorter poem, with which we shall close this essay, is The Kingdom of God, subtitled, In No Strange Land. Here again Thompson reverses another fatuous assumption when we think of the Divine as remote and difficult to locate. A second subtitle for this poem could be, Under Your Nose. Poignantly, all the locations identified in this poem are the very sites of Thompson’s degradation and struggle; sites made radiantly holy by a poetic vision steeped in Catholic faith. O World Invisible, we view thee, O World Intangible, we touch thee, O World unknowable, we know thee, Inapprehensible, we clutch thee! Does the fish soar to find the ocean, The eagle plunge to find the air – That we ask of the stars in motion If they have rumour of thee there? Not where the wheeling systems darken, And our benumbed conceiving soars! – The drift of pinions, would we hearken, Beats at our own clay-shuttered doors. The angels keep their ancient places; – Turn but a stone, and start a wing! ‘Tis ye, ‘tis your estranged faces, That miss the many-splendoured thing. But (when so sad thou canst not sadder) Cry; – and upon thy so sore loss Shall shine the traffic of Jacob’s ladder Perched betwixt Heaven and Charing Cross. Yea, in the night, my Soul, my daughter, Cry, – clinging Heaven by the hems; And lo, Christ walking on the water, Not of Genesareth, but Thames!

3 Comments

Bill Exley

14/10/2019 05:19:29 pm

Thank you for the excellent essay on Newman and Thompson, and for directing our attention to that moving poem, "Lead, Kindly Light".

Reply

Jim Ross

14/10/2019 05:59:35 pm

When a poem is enclosed in a book, you know where to find it, and so you do not look. Thank you Herman for surprising me with these two gems. They found me in a melancholy state, just to receive them.

Reply

17/10/2019 03:02:07 pm

I heartily second Jim's (Ross) pithy observation regarding book-enclosed and virtually forgotten poem. Even more heartily do I brighten in surprise at "these two gems". They, however, do not find me in a melancholy state, but in the awe of deepened re-discovery!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed