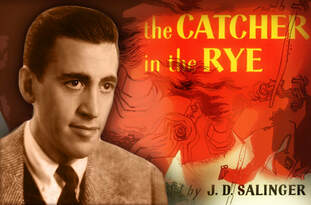

LONDON, ONTARIO – Like most adolescents of the last three or four generations who were not averse to picking up a book and pondering the meaning of existence, my first encounter with The Catcher in The Rye (1951), the only novel so far published by J.D. Salinger (1919 – 2010), was momentous. Driven by the pitch-perfect and miraculously timeless vernacular of its American adolescent narrator – 17 year-old Holden Caulfield – the novel movingly depicts the struggles of a bright and defensively caustic upper class kid who thinks he might be going crazy as he comes to discern his constitutional incapacity to fulfill the deepest longing of his heart to align himself with any cause or person that isn’t fundamentally compromised or (Holden’s favourite word) “phony”. Unlike a few of my friends who were equally thrilled by Salinger’s subsequent short story collections that primarily chronicled the existential travails of the impossibly precocious, artistically gifted and howlingly neurotic Glass family, I found these alternately precious and nihilistic tales to be pretty thin gruel. Through Nine Stories (1953) Franny and Zooey (1961) and Raise High the Roof Beams, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction (1963), I frankly charted an alarming descent in authorial rigour and inventiveness, each successive volume more attenuated and exasperating than the one before.

It was sobering to re-read The Catcher in The Rye as an adult when my own kids were briefly falling under its spell. In helping them churn out book reports for school, I reacquainted myself with the novel. And while I still marveled at Salinger’s accomplishment in capturing that voice, I now found that I had precious little use for just about everything that voice had to say; that I was now repelled by the book’s over-all contention that it simply isn’t possible to become an adult and maintain any sort of integrity. While it would be clearly unfair to hold Salinger responsible for the appeal of his novel to unhinged psychos, one can nonetheless discern why its message of ultimate futility would have registered so strongly on the minds of no less than three American assassins. (The good news is that its 64,999,997 other readers have reported no psychotic side-effects.) A few years ago I read David Shields’ and Shane Salerno’s revelatory Salinger (2013); a 700 page tome which was published as a complement to Salerno’s two-hour film documentary of the same title. While he still lived, the reclusive and litigious Salinger had been ruthlessly effective at hobbling and starving any would-be biographers who came in search of details or contacts with an eye to fleshing out his life story. While Salinger’s co-operation was never going to be had, all other constraints to telling his story fell away with his death in 2010. Salerno and Shield’s book went a long way to explaining how Salinger got so miserably stuck - both as an artist (he stopped publishing altogether in 1965 when The New Yorker ran one final mystifying installment of the Glass family saga, Hapworth 16, 1924) and as a human being. Salinger married three times and had at least twice that many dalliances; always - shades of Woody Allen - with young girls on the cusp of womanhood who’d then be rejected the moment they started to mature. The most notable of his live-in ingénues was the aspiring writer Joyce Maynard who came to his attention in 1972 when her long essay, An 18-Year Old Looks Back on Life, was featured as the cover story in The New York Times Magazine. Within one week of publication, Maynard had a contract with Doubleday to expand her essay into a book-length memoir and a fan letter-cum-overture from J.D. Salinger which soon impelled her to move in with the 53 year-old master who quickly deflowered her, grew bored with her and then booted her out shortly after her 19th birthday. In the book with Salerno, David Shields summarizes Salinger’s modus operandi as a despoiler of adolescence: “The same pattern recurs throughout his life: innocence admired, innocence seduced, innocence abandoned. Salinger is obsessed with girls at the edge of their bloom. He wants to help them bloom. Then he blames them for blooming.” Maynard, at least, got her own book out of the traumatic experience, At Home in The World, published in 1998 which gave the world its first glimpse of just how creepy old J.D. could be. And it really was a pretty obvious slip-up for a man who coveted his privacy with such vigilance to make a move on a young girl he already knew to be a widely read memoirist. Salerno and Shields tell us how Salinger came to hold such a stunted and destructive vision of what it means to grow up or to love. Born to a taciturn Jewish father who was convicted of price-fixing in his meat-importing business (including verboten hams) one can see where the young writer cottoned on to the idea that adulthood innately entailed hypocrisy and corruption. A smothering Irish-Catholic mother in whose eyes he could do no wrong initially trained him to take the support of women for granted. And then, when the first and perhaps only real love of his life, Oona O’Neill (daughter of the playwright Eugene), abruptly broke off their long engagement to marry the considerably older Charlie Chaplin, a shattered Salinger learned another debilitating lesson – to not trust women. Any remaining hope that Salinger might find a way to grow into some sort of responsible adulthood was finished off by his heroic participation in five of the bloodiest battles of World War II. His initiation to the world of combat was the full-force assault of D-Day where he landed on Utah Beach. And his wartime experiences were brutally capped off in the spring of 1945 when he was one of the first Americans to enter a Nazi death camp and confront the full horror of what grown men can do. With a backlog of betrayal and atrocity like that to ponder, it is perhaps no real mystery why a man of such finely tuned gifts never did learn to reconcile the near-holy esteem he felt for the adolescent sense of wonder and possibility – just think what we could be if we found a constructive way to harness the sensitivity and aspiration of youth – with a world that seemed determined to stamp out such qualities as soon as they appeared. And what dismal self-recrimination he must have felt in more reflective moments when this ageing chronicler of youth's beauty understood the role he personally played over and over again as a despoiler of that beauty. It would be enough, one suspects, to make it impossible to continue writing at all. Though he published nothing in the entire second half of his life, Salinger always claimed that he was continuing to beaver away at his Glass family chronicles. With Catcher in the Rye alone dependably selling a quarter million copies every year, he no longer felt any need to expose these characters he loved so lavishly to an uncomprehending and insufficiently appreciative public. Upon his death it was announced that the publication of never-before-seen material from Salinger’s vault was going to commence sometime between 2015 and 2020 with a collection of yet more stories about the Glass family. Well, four fifths of the way into that confidently projected renaissance, we’re still waiting for anything resembling a flood of fresh literary treasure to get underway. So far, not even a trickle. This winter to kick off the centennial of Salinger’s birth, his publisher, Little-Brown, has issued a deluxe, hardbound, box-set of the same four titles that have been available for more than half a century already. This commemorative edition of the same old books isn't just unnecessary; it also comes with a not-so-special list price of one hundred smackers. And to continue the year-long celebrations of such an important anniversary, these scarcely re-warmed re-issues will soon be followed up by . . . well, let me consult the publisher's prospectus and see what else is coming down the pike . . . uh . . . nothing else at all, actually. I begin to suspect that the great Hemingway biographer, A.E. Hotchner, had it right when he darkly joked several decades ago: “What if after all these years when Jerry’s been in his block house and allegedly writing all this stuff that’s too good for people to see because they’re going to distort it; what if when Jerry dies and they go into his vault and they open up his alleged treasure trove, what if there’s nothing there? . . . It would be a divine ploy, wouldn’t it?”

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed