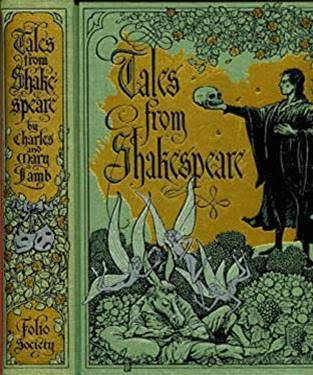

The Dome of St. Paul's Cathedral, London England The Dome of St. Paul's Cathedral, London England LONDON, ONTARIO – In his sublime but too-little known study from 1983, A Portrait of Charles Lamb (1775–1834), British biographer, professor and literary critic, Lord David Cecil, paid homage to the magically congenial essayist who wrote under the pen name of 'Elia'. Cecil was an old man by the time he rendered his tribute to a beloved writer who'd given him a lifetime of pleasure. And though his book is quite short, Cecil knows just which tales to tell, which passages to quote, so as to make Lamb's appeal comprehensible, and even contagious, nearly two centuries after his death. Charles Lamb’s outwardly uneventful life of fifty-nine years straddled the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Though they only co-existed for nine years, the figure Lamb is most commonly bracketed with in the imagination of the reading public is the great Samuel Johnson. The monumental Johnson and the impish Lamb were hardly two peas in a pod. Each writer came with a generous measure of quirks and encountered many setbacks and failures in the wobbly trajectory of his so-called career. But both won recognition as figures of pronounced integrity who had the courage to endure what must be borne without bitterness or resentment. One reason why we feel we know them a little better than so many of their literary peers is because they also turn up with impressive frequency in accounts penned by their contemporaries, giving us multiple glimpses of the striking originality of both writers' characters and the unfailing spontaneity of their wit. If Johnson remains more completely fixed in the public eye today while Lamb seems to be falling away, I think that is largely attributable to the magisterial account of Johnson’s life by James Boswell in what is broadly hailed as the first great biography in the English language. All of Johnson – or at least enough of Johnson to keep him vividly alive – can be found within the covers of Boswell's remarkable book. Whereas a little assembly is required – plucking bits from here and there, by his own hand and by others – to piece together a similarly rounded and expressive portrait of Charles Lamb. Lamb and Johnson both slaved away at a time when it was wretchedly difficult for a writer to earn anything approximating an adequate living and the shy, less ambitious Lamb never did make a go of it strictly on the avails of literature. Both were bedeviled by melancholic temperaments but neither succumbed to gloom for long; keeping themselves afloat through the careful nurturing of friendships old and new. And both men became human fixtures – widely recognized mascots you could almost say – of the London, England of their day. In the twentieth century, the gifted illustrator, E.H. Shepherd, produced two separate volumes choc-a-bloc with architectural sketches of each writers’ homes and haunts. To give his readers the distinct flavor of the playful sort of stoicism that was a hallmark of so much of Lamb’s prose, David Cecil opened his biography with this snippet from a late essay on sixteen Popular Fallacies in which our recently retired author refutes the suggestion, “That We Should Rise with the Lark”: “AT WHAT PRECISE minute that little airy musician doffs his night gear and prepares to tune up his unseasonable matins we are not naturalists enough to determine. But for a mere human gentleman – that has no orchestra business to call him from his warm bed to such preposterous exercises – we take ten, or half after ten (eleven, of course, during this Christmas solstice) to be the very earliest hour at which he can begin to think of abandoning his pillow. To think of it, we say, for to do it in earnest requires another half hour’s earnest consideration . . . Why should we get up? We have neither sun to solicit, nor affairs to manage. The drama has shut us up at the fourth act. We have nothing here to expect, but in a short time a sick-bed, and a dismissal. We delight to anticipate death by such shadows as night affords. We are already half acquainted with ghosts. We were never much in the world. Disappointment early struck a dark veil between us and its dazzling illusions. Our spirits showed grey before our hairs. The mighty changes of the world already appear as but the vain stuff out of which dramas are composed . . . We once thought life to be something, but it has unaccountably fallen from us before its time. Therefore we choose to dally with visions. The sun has no purposes of ours to light us to. Why should we get up?” Cecil chose this selection cannily. It is quintessential, forty-proof Lamb in which our man gaily skips out to the farthest edge of what can be said by the non-suicidal and has himself a frolic. Does one need to point out that a truly resigned or fatalistic soul does not write with that kind of crackle and fizz? Indeed, so dismally tethered a man does not take up his pen at all because what would be the point of that in this wretched vale of tears and strife where nothing matters anyway? Yes, it’s shot through with dark undertones but this essay on pointlessness and finitude positively shimmers with wonder and delight. In a spirit of "you either get it or you don’t," Cecil planted that passage right up front so as to ward off any potential readers on whom Lamb’s special gifts would be wasted. Adored – and sometimes resented - for his high spirits and impulsiveness, Charles Lamb once leapfrogged over a perfect stranger’s back at a party as the unsuspecting soul was bent over tying his shoe. It was the kind of impetuosity which could give a chap a reputation for craziness. And insanity did indeed "run", as they say, in Charles’ family. From a very young age Charles and his siblings were aware of the all-too possible risk that they would some day crack up and his Aunt Hetty took Charles aside as a teenager and warned him that it would be unwise to ever think of marrying or having children of his own. Really, she persuaded him, it was best not to pass on such fragile proclivities. And so at the age of twenty-one (and to the surprise of no one in his family), Charles flipped out, breezily confessing to his good friend, the poet Samuel Coleridge: “My life has been somewhat diversified of late. The six weeks that finished last year and began this, your very humble servant spent very agreeably in a mad house at Hoxton – I am somewhat rational now and don’t bite anyone. But mad I was – and many a vagary my imagination played with me.” Later in the letter Lamb mentions the disembodied voices he heard, the hallucinations he saw, the conviction he felt that he was somehow living the life of the central character in a play he had recently seen.  Mary and Charles Lamb Mary and Charles Lamb According to Coleridge, Leigh Hunt, William Wordsworth and other great souls whose testimony we can trust, there wasn’t a kinder, funnier and more sympathetic friend than Lamb. While he seems to have evaded the dismal entrapments of full-blown alcoholism, Lamb did regularly imbibe to keep the psychological collie-wobbles at bay. All of Lamb's essays, plays and poetry take up about half of the 1,000 pages of the Modern Library edition devoted to his work; a modest output compared to any of his contemporaries listed above. One reason why he wrote comparatively little was because he continually sought out the distracting company of others to, as he put it, “get between one’s self and Eternity”. The remaining half of the cherished literary remains of Charles Lamb are the hundreds of evocative letters he dashed off to his friends on those nights when he couldn’t find someone with whom to share his bottle of port. So far we have described a talented, lovable writer with a pretty shaky grip on reality, yet Lamb’s brief incarceration at Hoxton over Christmas of 1795, would prove to be his only period of confinement. If you’ve ever talked with people who’ve slipped over the edge for a while or for keeps, they will often speak about the element of choice; that yes, it was getting hard to cope but just before they succumbed, they distinctly remember opening a kind of door and saying, “Fuck it, let’s just give in to this and see what happens.” And sometimes those who manage to work their way back from that murky terrain do so, not because the circumstances of their lives have improved that much or at all, but because they suddenly recognize madness as a kind of indulgence which they can no longer afford. This certainly seems to have been the case with Charles Lamb who had ample cause to realize a mere nine months after his own incarceration that if he didn’t find a way to hold things together mentally, then life would effectively be over for the person he loved most in this world. Charles’ sister Mary – ten years his elder, the soulmate of his life, and arguably more of a mother to him than his actual mother – was inclined to fits of madness much more frequent and debilitating than his own. All the troubling signs of another episode for Mary were flaring up in September of 1796 and not even one day after Charles failed to solicit the help of her usual attending physician who was away on vacation, Mary's reason shattered in an unprecedentedly disastrous way. Charles wrote of the appalling tragedy to Coleridge: “MY DEAREST FRIEND – White, or some of my friends, or the public papers, by this time may have informed you of the terrible calamities that have fallen on our family. I will only give you the outlines: – My poor dear, dearest sister, in a fit of insanity, has been the death of her own mother. I was at hand only time enough to snatch the knife out of her grasp. She is at present in a madhouse, from whence I fear she must be moved to an hospital. God has preserved to me my senses. I eat, and drink, and sleep, and have my judgement, I believe, very sound. My poor father was slightly wounded, and I am left to take care of him and my aunt. Mr. Norris, of the Blue-coat School, has been very kind to us, and we have no other friend; but thank God, I am very calm and composed, and able to do the best that remains to do. Write as religious a letter as possible, but no mention of what is gone and done with. With me ‘the former things are passed away,’ and I have something more to do than to feel. God Almighty have us all in his keeping!” Charles was a quirky, ungainly fellow, not much of a financial prospect, and probably not too attractive to the opposite sex. He may not have been a likely candidate for matrimony anyway but from that point on, he was reconciled to the necessity of heeding Aunt Hetty’s advice. The medical authorities were all for packing Mary away in the asylum for the rest of her life until Charles stepped forward and solemnly vowed to take complete and lifelong responsibility for his sister. Not only did this decision cancel out the possibility of marriage, it also meant that Charles would never be able to leave his job as a clerk with the East India Office to try his luck at a career of writing full time as so many of his friends were able to do. Charles Lamb was only twenty-two years old when all of the prospects and hopes he may have entertained for the rest of his life were suddenly grounded. It may seem a pitifully circumscribed existence but Charles Lamb’s life and so much of his writing testify to the fact that it is perspective – not vista – which is the key factor in determining happiness. The same man who could explore the pathetic winding down of the retired man’s life with so much fondness and verve, had an eye for the transcendent beauty to be savoured in even the commonest surroundings. Responding to a letter from Wordsworth in which the poet had claimed that only in the rolling hills of the Lake Country could a man’s spirit be revived, Lamb whipped off this little hymn about the few acres of London where he lived and worked for nearly all of his life: “The lighted shops of the Strand and Fleet Street, the tradesmen and customers, coaches, wagons, playhouses, all the bustle and wickedness round about Covent Garden . . . the crowds, the very dirt and mud, the Sun, shining upon houses and pavements, the print shops, the old book stalls . . . coffee houses, pantomimes . . . all these things work themselves into my mind and feed me, without a power of satiating me. The wonder of these sights impels me into night walks about her crowded streets, and I often shed tears in the motley Strand from fullness of joy at so much life.” Lamb did have deeply embedded Christian convictions and, as we have seen, in times of crisis he would seek specifically Christian counsel and draw strength from it. But in the general run of things, when he was confident that he could handle whatever challenges life threw his way, he found regular observances or prayers or attendance at church to be ineffectual and even meaningless. David Cecil tells a wonderful story from his childhood about Lamb’s inability to take piety at face value which I think might shed a little light on his attitude toward the routines of organized religion: “Charles’ reading had made him early aware of the existence of wicked people. Once, when he was a very little boy, Mary took him for a walk in the churchyard. He examined the inscriptions on the tombstones and was puzzled by the fact that they only mentioned the virtues of the persons commemorated, as if they had no faults worth speaking of. Charles paused and pondered: ‘Mary, where are the naughty people?’ he asked.” In the wake of that murderous catastrophe, Mary’s madness would ebb and flow. She was never able to get completely clear of it for even a year – and taken all in all – she was mad for half of her adult life. Neighbours of the Lambs always knew what was up when Charles could be seen, suitcase in hand, weeping as he led his sister to the hospital up the road to book her in for another spell. Yet the other half of the time, this pair managed to maintain an eccentric and happy and remarkably productive home. To help keep his sister focused on something constructive, Charles and Mary wrote three children’s books together (indeed, she wrote the lioness’s share of all of them) – some original tales, a re-telling of The Odyssey, and their most popular volume which has never gone out of print, Tales from Shakespeare.  In the last year of Charles’ life, Mary’s condition worsened. While she wasn’t violent, there were no more lucid intervals. Mary now was to be permanently housed in a pleasant enough facility called Walden Cottage and Charles decided that if he couldn’t have his sister at home with him, then he’d just have to move into the facility with her. Explaining his action to a mystified friend, Charles wrote: “Have faith in me! It is no new thing for me to be left to my sister. When she is not violent, her rambling chat is better to me than the sense and sanity of this world. Her heart is obscured, not buried; it breaks out occasionally; and one can discern a strong mind struggling with the billows that have gone over it. I could be nowhere happier than under the same roof with her." Indeed, a little further on in that letter, Charles makes it clear that his own identity and his sense of his place in the world are inextricably embedded in his relationship with his sister: "Her memory is unnaturally strong; and from ages past, if we may so call the earliest records of our poor life, she fetches thousands of names and things that never would have dawned upon me again, and thousands from the ten years that she lived before me.” Mary Lamb lived on alone for ten more years at Walden Cottage where she finally died at the age of 79; her madness seeming to cushion her from the full realization that her lifelong protector and best friend was dead. Or perhaps, as Lord David Cecil speculates in his book’s conclusion, she realized the truth completely enough but, contrary to the common assumption, “he had always needed her more than she needed him.”

2 Comments

Bill Craven

24/8/2020 11:08:47 am

Reply

Max Lucchesi

25/8/2020 04:22:45 am

Again, another great piece Herman. May I though, champion the cause of John Clare 1793-1864, Charles Lamb's contemporary. Clare the son of a farm labourer was born in the village of Helpston Northamptonshire. Though a child labourer he did receive some education in the church's vestry in the nearby village of Glinton until he was 12 years old. As a young adult he worked as a potboy, met his first love Mary Joyce whose father, a prosperous farmer forbade them to see each other. He became a gardener, joined the Militia, roamed for a time with Gypsies and worked as a lime burner. Always in poor physical health due to childhood malnutrition, in 1817 he fell seriously ill and had to resort to Parish Relief. Along the way he had found James Thompson's 'The Seasons' and was inspired to write poetry. In 1820 to help his father avoid eviction he offered his poetry to Edward Drury, a local bookseller who sent them to his cousin John Taylor of Taylor&Hessey, publishers of John Keats. Taylor was impressed enough to publish his first volume 'Poems Descriptive of Village Life' and a year later 'Village Minstrel and Other Poems'. While both volumes met with critical acclaim Clare's life was made no easier. He felt uneasy and alienated in London's literary life and at home his neighbours considered him a curiosity and shunned him. Though he continued to write and have his poems published, they never again received the acclaim of the first two volumes and his life was plagued by poverty, sickness, depression and insanity, until finally in 1841 he was committed to Northampton General Lunatic Asylum. His care there was paid for by Earl Fitzwilliam. He remained there for the rest of his life under the care of a humane doctor, Thomas Octavius Pritchard, who encouraged and helped him to write. It was there that he wrote most of his best work, On his death his remains were taken to Helpston and buried at St. Botolphs Churchyard. The inscription reads, "In memory of John Clare The Northamptonshire Peasant Poet. Poets are born not made". His reputation grew after his death and today he is considered England's finest rural poet and among her greatest romantic poets.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed