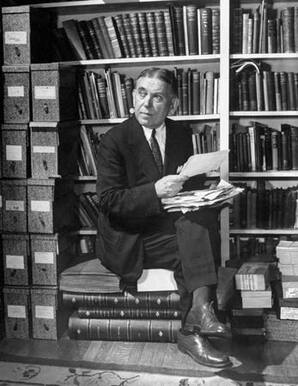

H. L. Mencken (1880 – 1956) H. L. Mencken (1880 – 1956) LONDON, ONTARIO – Though I read him a lot – and very avidly indeed – through the 1980s and ‘90s, it’s been a while since I’ve splashed about in that bracing fount of caustically humorous wisdom that goes by the name of Henry Louis Mencken (1880-1956). Every thinking man’s favourite contrarian claimed that he always wrote for his own pleasure, to attain “that feeling of tension relieved and function achieved which a cow enjoys on giving milk.” And it shows. No matter how cantankerous or upsetting his dispatches from the front line of politics, religion or the arts might be – and whether you agree with him or not – the reader almost always feels an accompanying pleasure at seeing an insight or a contention so vividly and aptly expressed. Though he lived for most of his life in his German family’s Baltimore home and worked for most of his career as a columnist and editor for the not particularly prestigious Baltimore Sun, Mencken amassed a national and international audience for the books he wrote and the pioneering magazines he either overhauled and edited, or founded and edited – respectively, The Smart Set and The American Mercury. Neither of these magazines had a budget to compare with a more established organ like The Atlantic, but Mencken was a shrewd critic of all the arts and knew how to spot fresh literary talent in the bud. Dozens of writers – including such heavy hitters as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Willa Cather, Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, Sinclair Lewis and Joseph Conrad – were helped by his mentoring and promotion in the early stages of their careers. What occasioned my latest rejuvenating immersion in the life and work of this jolly butcher of sacred cows was finally coming into possession of Terry Teachout’s breezy 2002 biography, The Skeptic: A Life of H.L. Mencken. Teachout brings this already familiar (to me) chronicle in at a comparatively modest 350 pages; avoiding the nit-picking longueurs of Fred Hobson’s notably joyless and nearly twice-as-long Mencken bio from 1994. I suspect that leaden doorstop of a tome – which is considered ‘definitive’ in certain dim circles – was more instrumental than anything else in making me give the Sage of Baltimore a rest for a couple of decades. Employing the same humane and culturally informed breadth of insight which distinguishes his prolific arts journalism (as well as his biographies of figures like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and dance choreographer, George Balanchine), Teachout manages to take note of Mencken’s blind spots and flaws – such as a reflexive but never aggressive anti-Semitism that ultimately hobbled him more than it ever harmed anyone else – without losing sight of what made him such a powerfully liberating and influential writer. As he sums things up in this biography’s conclusion: “One cannot help admiring the stubborn way in which Mencken the self-made philosopher grapples, in his unpretentious, take-no-prisoners way, with the permanent things: the limits of art, the rule of law, the meaning of life. The simplicity, one comes to realize, is inseparable from the message. In Mencken, style and content are one, and the resulting alloy is more than merely individual. It is a matchlessly exact expression of the American temper. He was to the first part of the twentieth century what Mark Twain was to the last part of the nineteenth – the quintessential voice of American letters.” Born into a comfortable family of cigar manufacturers, 18 year-old Henry’s ardent desire to see if he could make his way as a journalist was being thwarted by obligations to the family firm until his father suddenly collapsed of a kidney infection on New Year’s Eve of 1898. As the rattled and anxious lad raced through the cold and blustery night to fetch a doctor, past homes where happier families were preparing to ring in the final year of the 19th century, he couldn’t help realizing the potentially positive implications of his father’s threatened demise. Panting his way through drifts of snow, he kept repeating to himself, “If my father dies, I’ll be free at last.” A few weeks later his father was buried and, slicking down his hair and donning his best suit of clothes, Mencken turned up at the beginning of the evening shift in the city room of The Baltimore Morning Herald to see if he could pick up an assignment. There was nothing on offer that first night and he returned every day for the next four weeks until – on an evening when Baltimore was paralyzed by yet another blizzard – a scrap was tossed to the hungry pup. “Go out to Govanstown,” he was told, “and see if anything is happening there. We are supposed to have a Govanstown correspondent, but he hasn’t been heard from for six days.” By 11 p.m. Mencken had filed a two-sentence report on the theft of a horse and buggy and several sets of harness from a Govanstown livery stable and then whipped off another one-sentence item about a cineograph exhibition in a Baltimore church hall. When both these unsigned, unpaid stories, “exactly as written,” made it into the Friday, February 24th, 1899 edition of the Herald, Mencken wrote, “There ran such thrills through my system as a barrel of brandy and 100,000 volts of electricity could not have matched.” He had achieved his first foothold in what he would call “the maddest, gladdest, damnedest existence ever enjoyed by mortal youth . . . I was at large in a wicked seaport of half a million people, with a front seat at every public show, as free of the night as of the day, and getting earfuls and eyefuls of instruction in a hundred giddy arcana, none of them taught in schools.” No, those first two innocuous and miniscule reports were not the stuff of which journalistic legends are made. A far truer flag of what would turn out to be Mencken’s unique gift to the reading world was that private, nine-word utterance from seven weeks before: “If my father dies, I’ll be free at last.” When he soon worked up the courage to commit that sort of notion to print – the kind of insight that politeness and convention agree must never be given voice – that was when this cigar-chomping, two-finger typist’s star went soaring into the journalistic firmament where it continues to glow a hundred years later. Throughout his career Mencken strove “to stir up the animals,” he said; to offend old ladies of every age and gender. And he does so just as effectively today as in his heyday of the twenties and thirties. The value of a great polemicist is never his meticulous fairness or sober attention to the nuances of any situation; it’s in the vigour and the sweep and the wit of the assertions he levels at oppressive orthodoxies and intellectual climates that sap courage, stifle debate and suffocate free thought. If such writers don’t accelerate your pulse and occasionally make you catch your breath in quickened disbelief, they’re not doing their job. Take hold of your pearls as I bombard you for a few moments with a modest sampling of some of my favourite turbo-charged missiles of 40-proof Menckeniana: “Puritanism: The haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.” “School days, I believe, are the unhappiest in the whole span of human existence. They are full of dull, unintelligible tasks, new and unpleasant ordinances, brutal violations of common sense and common decency. It doesn't take a reasonably bright boy long to discover that most of what is rammed into him is nonsense, and that no one really cares very much whether he learns it or not.” “A judge is a law student who marks his own examination papers.” “Every normal man must be tempted, at times, to spit on his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin slitting throats.” “On some great and glorious day the plain folks of the land will reach their heart's desire at last, and the White House will be adorned by a downright moron.” “The urge to save humanity is almost always a false front for the urge to rule.” “When women kiss it always reminds one of prize-fighters shaking hands.” “Wealth: Any income that is at least $100 more a year than the income of one’s wife’s sister’s husband.” “Every decent man is ashamed of the government he lives under.” “Conscience is a mother-in-law whose visit never ends.” “The government consists of a gang of men exactly like you and me. They have, taking one with another, no special talent for the business of government; they have only a talent for getting and holding office. Their principal device to that end is to search out groups who pant and pine for something they can't get and to promise to give it to them. Nine times out of ten that promise is worth nothing. The tenth time is made good by looting A to satisfy B. In other words, government is a broker in pillage, and every election is sort of an advance auction sale of stolen goods.” “It is the classic fallacy of our time that a moron run through a university and decorated with a Ph.D. will thereby cease to be a moron.” (I love his use of “run through”, calling to mind a sheep being herded through disinfectant dip.) “Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard.” “Don't overestimate the decency of the human race.” “An idealist is one who, on noticing that roses smell better than a cabbage, concludes that it will also make better soup.” “We are here and it is now. Further than that, all human knowledge is moonshine.” “It is now quite lawful for a Catholic woman to avoid pregnancy by a resort to mathematics, though she is still forbidden to resort to physics or chemistry.” “A church is a place in which gentlemen who have never been to heaven brag about it to persons who will never get there.” “Morality is doing what is right, no matter what you are told. Religion is doing what you are told, no matter what is right.” “The chief contribution of Protestantism to human thought is its massive proof that God is a bore.” “I can’t understand the martyr. Far from going to the stake for a Great Truth, I wouldn’t even miss a meal for it.” “God is a comedian, playing to an audience too afraid to laugh.” Mencken was first and foremost a working – and frequently an over-worked – journalist; usually writing too quickly and too distractedly to develop his book length studies on Nietzsche, Shaw, statecraft, religion and the eternal mystery of women into anything much more distinguished than stitched-together columns. This is not to denigrate his utter mastery as a columnist. Two fine, fat collections of these which I particularly treasure are the career-sweeping anthology which the master himself pulled together in 1949, A Mencken Chrestomathy, and Mencken biographer Marion Elizabeth Rodgers’ 1991 selection of pieces which the Chrestomathy missed, The Impossible H.L. Mencken.  Doing his research for "The American Language" Doing his research for "The American Language" Because of his familial heritage and instinctual love for German culture and because of his inability to parrot any political line that he did not hold himself, he was persuaded to take two voluntary leaves of absence from his editorial chair at the Sun for the duration of both Germany-driven World Wars. His time on the sidelines was not wasted. His best-developed and most rewarding books were written during those furloughs. During the First World War he produced The American Language of which Teachout declares: “It was no mere list of amusing Americanisms. In all its various editions, the book was an exhaustively documented examination of the myriad ways in which American English had grown away from the mother tongue, whether by altering old words or coining new ones. These differences had long been noted on both sides of the Atlantic, but never before had anyone gone to the trouble of cataloguing and analyzing them in such copious and illuminating detail . . . Though he was an amateur scholar, there was nothing amateurish about his scholarship.” And the Second World War saw him produce his hugely popular trilogy of memoirs, Happy Days (covering his childhood), Newspaper Days (on his early years as a working journalist) and Heathen Days (outlining his later life). Heathen Days is frankly a little scrappy; an all-round less cohesive work. But the first two are brass-bottomed masterpieces. I would put Happy Days up there with Annie Dillard’s An American Childhood as a magically evocative account of a very particular child’s early life which somehow attains a luminous universality. On the fifth page, we know this will be a memoir like no other when he gazes at a photo of his infant self and then launches into this equally unsettling and disarming reflection: “The science of infant breeding, in those days, was as rudimentary as bacteriology or social justice, but there can be no doubt that I got plenty of calories and vitamins, and probably even an overdose. There is a photograph of me at eighteen months which looks like the pictures the milk companies print in the rotogravure sections of the Sunday papers, whooping up the zeal of their cows. If cannibalism had not been abolished in Maryland some years before my birth I’d have butchered beautifully.” Here in a chapter entitled Larval Stage of a Bookworm, Mencken recounts his momentous first reading of Huckleberry Finn, a book he would revisit at regular intervals for the rest of his life: “If I undertook to tell you the effect it had upon me my talk would sound frantic, and even delirious. Its impact was genuinely terrific. I had not gone further than the first incomparable chapter before I realized, child though I was, that I had entered a domain of new and gorgeous wonders, and thereafter I pressed on steadily to the last word. My gait, of course, was still slow, but it became steadily faster as I proceeded . . . at eight or nine, I suppose, intelligence is no more than a small spot of light on the floor of a large and murky room . . . [but Huckleberry Finn] was as transparent to a boy of eight as to a man of eighty, and almost as pungent and exhilarating.” And this workaday scribe who entered the halls of journalism nearly eighty years after Mencken, found his subsequent volume, Newspaper Days, to be similarly transcendent of time and place in his wide-eyed evocation of the fizzing, world-by-the-tail excitement of what it’s like to be a young working writer with an assignment, a deadline and a fabulous story that you long to put across in a fresh and worthy way. Mencken’s two wartime sabbaticals from daily journalism were necessary because of his congenital inability to ever see Germany in a villainous light; a failure which temporarily put him out of favour with The Baltimore Sun’s readership. Teachout claims that Mencken badly underestimated and misunderstood Adolf Hitler: “He had no feeling for the darkness in the heart of man. He looked at evil and saw ignorance. To him, Hitler was Babbitt run amok, and he thought it inconceivable that such a buffoon could pull the wool over the eyes of the most civilized people on earth. Sooner or later they would have to catch on.” It seems a strange thing to say about a writer who could upset sensibilities with such ease and élan but there always was an underlying innocence and good-heartedness to Mencken. Though he had no regard for any religion and particularly relished laying into the imbecilities of the more fundamentalist Christian sects, this believer at least is always happy to hear whatever withering observations he has to share. While he might be a tad extravagant in his criticisms and denunciations, he was rarely mean about it and usually had the grace and fellow feeling to at least soften the blow with humour. With the exception of his scathing obituary notice of two-term congressman, William Jennings Bryan (whose testimony he had mocked in his reportage of the infamous Scopes / Monkey trial of 1925), Mencken never stooped to expressing contempt for people of any faith. While I might be tempted to subtract some demerit points for that atypical outburst, I'd then want to give them right back whenever I remember his touchingly charitable response in 1921 when he was asked to write his own epitaph: “If, after I depart this vale, you ever remember me and have thought to please my ghost, forgive some sinner and wink your eye at some homely girl.”

1 Comment

SUE CASSAN

6/8/2019 01:12:11 pm

This is great encouragement to dip into a writer known by reputation. A pearl is the writer who can capture the moment freshly, but somehow write for the ages. A quality you share, in your collections of essays. Thanks for the tip about a new, to me, author to try.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed