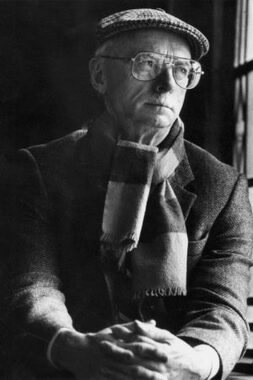

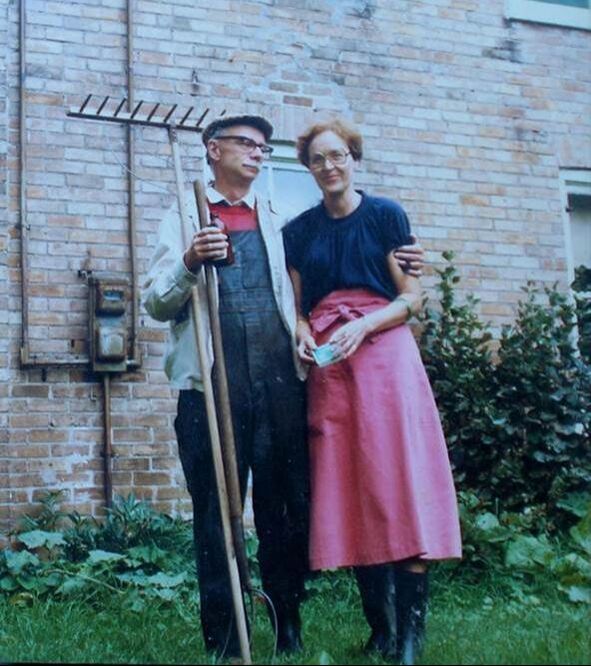

James Reaney Sr. (1926 – 2008) James Reaney Sr. (1926 – 2008) LONDON, ONTARIO – Abandoned at home for 90 hours of uninterrupted bachelor slovenliness this week, I was able to take a deep dive into my own journalistic archives and was, in turn, engrossed, surprised, appalled and delighted by what I found down there. As I waved my wife goodbye and strapped on my spelunking gear, I had a few definite items in mind that I was searching for and did indeed locate over the course of almost four days. But here’s what made this week so special. Once I committed to dropping down that hole, all manner of lost writings and red herrings came swarming into view and because I wasn’t expected anytime soon to come back up to cook or talk or change a lightbulb, I got yanked away in every possible direction and reacquainted myself with subterranean caverns and nooks that I hadn’t visited or considered in years. As a perpetual freelancer, I have spent almost half a century shaping different kinds of articles and commentary into forms that I can sell to a range of magazines and newspapers. And since starting up this blog eighteen months ago, I have been luxuriating in the freedom of not holding back on what can be said because I can’t go over 750 words; and not having to avoid certain subjects that are considered too arcane, too specialized, too religious or too personal and therefore won’t be deemed suitable for a more general readership. What most surprised me in this week’s wanderings all the way back to some of the very first articles I wrote, was the realization of just how much more space – both physical and intellectual – used to be accorded to writers in even the most hopelessly local publications. The dumbing down, the shrinkage, the ideological narrowness that now make London-based publications such very thin gruel for anyone who likes to read, these are all fairly recent developments of the last couple decades. (And quite implausibly, whenever you think they can’t possibly get any cheesier than this, they do.) So let me share my holiday experience by transporting you back to a more bountiful time 31 and a half years ago when James Reaney Sr. and Colleen Thibaudeau were still very much alive and could be the subjects of an 11-page magazine article. The Reaney Enigma first appeared in the December, 1987 issue of Ontario Living. Before it merged with London magazine, Ontario Living still fancied itself a magazine about homes so any feature article had to talk a little bit about architecture and furnishings. This made Jamie in particular just a wee bit skeptical about the whole enterprise but I think we ended up having a fair bit of fun with this niggling requirement. *********************** One of the most accomplished and influential figures on the Canadian literary scene of the last 40 years, James Reaney is almost invisible at home. When he is off the campus of the University of Western Ontario where he’s been a professor of English since 1960, London has never really known what to do with him. For his poetry and plays, Jamie has won three Governor General’s Awards, one Chalmers Award and been elected as a fellow to The Royal Society of Canada, yet locally, his 33 year-old son, James Stewart Reaney, once a sports writer and now general columnist with The London Free Press, is probably the better known of the two James Reaneys. (To keep it all straight, neither father nor son is known as James in intimate circles. The elder is Jamie to everyone but strangers and first year students and the younger is usually called James Stewart.) Though Jamie’s trilogy of plays on the Donnellys – Sticks & Stones, The St. Nicholas Hotel and Handcuffs – went on a national tour in 1975, playing theatres from British Columbia to New Brunswick and was solidly acclaimed as a milestone in Canadian theatre, here in London the plays were only ever staged at the Drama Workshop in University College and later at Saunders Secondary School. The Grand Theatre, perceived by most Londoners as the only theatre in town, passed over Jamie’s trilogy completely and instead presented Peter Colley’s far less ambitious play, The Donnellys. And the greater looms the man’s international legend, the harder it becomes for London to know just how to approach Jamie. A few years ago I hosted separate public readings for Jamie and his wife, the poet Colleen Thibaudeau at the Forest City Gallery, and their differences in presentation were striking. Though they both have the demeanour of classically distracted artists, their antennae ever extended and their minds seemingly focussed on everything except the matter at hand, Colleen has ways of grounding herself which Jamie has not. Colleen has never had the inclination or the opportunity to live entirely in her writing. Her years of mothering and taking care of Jamie’s father and other domestic concerns have kept her touch a common one. Her poems all mine themes accessible to anyone who’ll take the time to listen and, on the reading platform, she has the humility of the anxious amateur who’ll explain and illuminate, tell stories and jokes, and keep her audience with her. Jamie just didn’t have her kind of leeway, both because of his shyness and because of the layers upon layers of codified meaning in his work which would take too long to explain to the uninitiated. His reputation, his education and his immense bibliography all ensured that a good-sized audience turned out to listen to this thin, white-haired Gepetto of a man rip his way through a couple dozen selections but I know that at least half the ears in the house were mystified and lost by the obscurity of his references. His campus cronies at the back of the hall were with him every step of the way but those of us who aren’t on speaking terms with the Spenserian pastoral mode, who weren’t just certain who Sara Jeanette Duncan was, and who suspected that medieval exegesis was just a pretty term for antiquated scalp rash . . . we wished he’d stop hiding behind his books for a minute and talk to us instead. With his students such steam-rolling tactics are useful; they either catch up in a hurry or they fail. But a wider public can be easily put off when they assume that the man is unapproachable and doesn’t care if they understand him or not. Through my own oblivious gall, I learned early on that Jamie is indeed approachable. As the most esteemed writer in town, I figured he was eligible to have a look at a very messy novel I completed about ten years ago and I impulsively popped round to his house on my bike and stuffed the manuscript between his doors. Not only did he make the time to read it within a week, he even talked to me about it and made a number of helpful suggestions. Needless to say, he didn’t have to do that. And what I’ve known ever since that time is that this intimidatingly erudite man can be coaxed down from the ethereal atmosphere of academe and that if more people had a chance to meet the man – as husband and father, boy and student, as a more easy-going raconteur – it might do us all a world of good. On the night of my visit to the Reaney house on Huron Street in preparation for this article, Jamie had just blown in from his weekly visit to his ancestral farm near Stratford, where he’d been to the fall fair and consorted with his treasured box of childhood toys in the farmhouse attic. He’d caught a late train home and was just sitting down to reheated supper in the dining room as I arrived. This gave me a few minutes to poke around the house until we’d all sit down to dessert – a slightly battered apple pudding which had just arrived in the mail that day from friends out west. One of the most comfortable houses on earth, I think it would make a good cover feature for the first post-Apocalypse issue of Architectural Digest. It’s an old, two-storey, red brick house built to the centre-hall plan. The large lot – which until recently, Jamie regularly groomed with an old manual mower – slopes down in the backyard to the floodplains of the north branch of the Thames River. To the northeast one can clearly make out the spire of St. Peter’s Seminary and their particular stretch of Huron Street is one of the most heavily wooded sections to be found in the whole Forest City. A curving sidewalk runs from a streetlamp to the wide front verandah. You no sooner approach the front door than you discover a device which every home ought to have. Attached to the metal framework of the porch lamp by a string are a pencil and a pad of paper. It’s a sort of do-it-yourself answering machine with the built-in advantage that it screens out messages from illiterate pests who only use pencils to punch out the numbers on push-button phones. It doesn’t look particularly chic but it serves its function simply while introducing you to the timeless and very personal spirit of the place. Talking about student digs she once occupied in Toronto, Collen told me, “It was such an interesting place. There was so much going on, people dropping in all the time . . . I think that was when my bohemianism took over. I never again got interested in order or decency.” It can’t have been an easy thing to live in trendy North London these last 25 years amidst neighbours who wage ruinously expensive tone wars and never once get caught up in their shifting campaigns, but Colleen has managed to stand firm. The floors are nearly all linoleum, the odd throw rug cast about; one with a curling corner which is held flat by a rock. The piano is in the dining room because that’s where it fits and most days Jamie puts in an hour at the keyboard playing Bach or hymns or songs from Snow White with considerable proficiency and flair. Books cover every shelf and table surface in the house; overflow is arranged in stacks on both floors and obscures a good portion of the landing. Reference works and academic tomes are filed away on shelves while those that float from tables to stacks and appear to be the most recently read are contemporary works by younger writers with connections to the Reaneys – Don McKay, Christopher Dewdney, Michael Ondaatje. The walls are decorated with mostly original artwork, some by London artists and friends, a number of paintings and photographs by daughter Susan. In the front hall Colleen has pinned up a large square kerchief because she likes its design and people still talk about the party from a few years back when Colleen hung a dress up on the wall of the living room so everyone could enjoy its pattern and lines. That it worked, says as much for the Reaneys’ parties as Colleen’s unorthodox decorating schemes. Parties are often called on very short notice when companies of actor friends are moving through town. A more elaborate celebration was held about six years ago when Earl Birney was Western’s writer-in-residence. Colleen, true to form, didn’t invite us until the afternoon of the big day and my wife hemmed and hawed, not at all sure we’d be able to line up a babysitter in time. “But Emily’s invited too,” Colleen insisted, referring to our first-born who was then about six months old. “Don’t you think she’d like to meet Earl Birney?” Emily only squawked a little when Birney pressed up his great bearded mug to say hello. “Kids love me,” he said. “They all think I’m Santa Claus.” This uniquely inviting house is at its best when hosting that kind of affair. Writers and artists and actors and teachers swarm over every square foot of the main floor and at high tide, they even squat on the stairs in three or four conversational clusters, making trips to the upstairs bathroom slightly perilous but always interesting. They are the kind of parties that most people become too timid to throw after leaving university. But the Reaneys don’t care if the rugs get stained and if they had a single Royal Doulton figurine, Jamie would probably invite his guests to break it. What matters to them is the free and clamorous exchange of ideas – both in their work and their social lives – and this, above all else, is what their house has been designed to facilitate. Having partaken of the long-distance pudding, it was time to start the interview. Though Jamie was initially skeptical of the merits of a non-academic profile of his life and times, he warmed to the idea as the evening wore on, leaving the table every 20 minutes or so to pad about the house in fur-lined slippers and fish out old picture books and first publications to supplement his story. Though Colleen and Jamie can’t recall exactly when they first met, they’re certain that it must’ve happened on the campus of the University of Toronto where they both arrived in the fall of 1944, enrolled in English at University College. Colleen had come up from St. Thomas, propelled by scholarships and a love of learning imbibed from her school teacher father. “It was during the war,” Colleen remembers, “and the buildings weren’t heated. We wore our coats all the time. We took different options so, except for some of the English, we weren’t in the same classes very much. One day this impertinent person was sitting behind me and asked if I would please lower my coat collar. But that wasn’t the first time we met. I’m not sure if I lowered my collar or not.” Jamie had come from his family’s Stratford-area farm, also propelled by scholarships and a hunger for the work that lay ahead. But he was perhaps equally driven by a home situation which badly needed some distance to cool down. Jamie’s father was a dreamy and impractical man who never fully recovered from the horrors he’d witnessed and endured as a soldier in the First World War. He’d once had aspirations to be an actor in vaudeville and, from all accounts, was miserably miscast in life as a farmer. Jamie cherished his father’s sense of humour and cites him as “probably the single greatest role model of my life.” When his father went off to the mental asylum in London for a stay of undetermined duration, things were bad enough. Then Jamie’s mother took up with the hired hand, openly living with a man she wouldn’t be able to legally marry for another ten years and giving birth to two of his children. Socially, this was not a smooth move in the judgemental atmosphere of small town Ontario at the time. Held in exile and contempt by his hometown, feeling betrayed by his mother and bullied by this usurper of his father’s throne . . . Jamie was more than ready for a change of scene. This early domestic upheaval helps to explain so many of the puzzles embodied in Jamie as an artist and an adult – his apparent ambivalence about girls and dating while attending university; his lifelong taste for gothic stories (“Here in Ontario, gothic is how people think,” he told me; “It’s how they expect things to be”); and the uncanny depth of poetic insight he would eventually bring to the Donnelly trilogy, a study of the venom and judgemental hatred which rains down upon another distressingly chaotic family in another small southwestern Ontario town. But it only partially explains it. Millions of people experience worse traumas and never even write a limerick. For the rest was required a couple other of Jamie’s attributes – little things like a flash of literary genius and a tenacious commitment to his art.  Jamie and Colleen: student years Jamie and Colleen: student years For two developing poets and storytellers, one can hardly imagine a more exciting place to be in all of Canada at that time than the University of Toronto. Northrop Frye and Marshall McLuhan were teaching. Claude Bissell and Donald Creighton had just cooked up an innovative course combining Canadian literature and history (So that’s who Sara Jeanette Duncan is!), Robert Weaver helped with student publications like The Undergrad and Here and Now. Margaret Avison sought students out one at a time for consultation and The Undergrad editor, Paul Arthur, knew just which strings to pull in order to bring in visiting writers like A.M Klein, the multifarious Sitwells, Stephen Spender and W.H. Auden. Jamie and Colleen started getting their poetry published in some of the major Canadian quarterlies – Northern Review, The Canadian Forum, Contemporary Verse – and Jamie was also hitting his stride as a writer of short stories – lurid little shockers for the most part, quite Edgar Allan Poe-ish – with titles like The Bully, Clay Hole, and The Young Necrophiles. The most notorious of these stories was The Box Social, published in New Liberty magazine in 1947, in which a distraught woman sells her aborted fetus, hidden in a box lunch, to her old boyfriend. Laughing with lingering glee at the scandal these stories provoked, Jamie said, “You know, I’m still waiting for some publisher to bring out The Box Social and Other Stories. It seems that overdrive is the only gear that Jamie has ever known and in 1949 at the tender age of 23, he pulled off an astonishing triple coup – earning his M.A. (as did Colleen), landing a teaching position at the University of Manitoba and winning the Governor General’s Award for his first collected volume of poems, The Red Heart, which had been published by McClelland & Stewart. Though even his dry spells look like most other writers’ high tides, Jamie insists that with the move out to Winnipeg in the fall of ’49, he hit a difficult patch, unsure just what to do next. Part of it had to do with his discombobulation at having to conduct university life from the other side of the desk. He’d been lured out to The University of Manitoba when they promised him he’d be able to teach creative writing – which he did – but only for three hours a week. What he didn’t see coming was the rest of his timetable teaching introductory English to foreign freshmen, mostly from Nigeria. As Jamie recalls it, “There was some loose clause regarding student immigration so that suddenly everybody came to Manitoba to get into medical school and I got them all first year. That really floored me.” Five stimulating years in Toronto hadn’t exactly prepared him for higher learning on the frontier. “Some grafter had a parcel of land ten miles outside of Winnipeg, so that’s where the government built the university. The kids from the north end of town literally had to travel 20 miles to college, so they left campus as early as they could in the afternoon and the place was absolutely deserted. Except there was a huge residence that looked like the Czar’s winter palace and it was filled with aggy dips and other terrible types who probably slept 13 to a bed in these awful little apartments called bullpens.” And what, you might be wondering, is an ‘aggy dip’? “Agricultural diploma students. They don’t even get a degree in agriculture; they get a diploma. When John Hirsch was there trying to teach English, they burnt a couple chairs and a desk in his room, lit a fire in the wastepaper basket and started tearing things apart. They couldn’t stand books. Poor Hirsch never survived. He was even shyer and more giggly than I was when he started out.” Though it took him a couple years to rise to the challenge, Jamie eventually became braver at teaching. “It was a matter of changing my character a bit and becoming more fearsome. If you learn their names right off the top, then it becomes much easier to nail them. Put up or shut up.” Jamie seems to speak for both himself and Collen when he says, “I didn’t understand anything about dating or getting engaged or married.” They just did it, somehow, on Colleen’s home turf in St. Thomas on December 29th, 1951 – Colleen’s birthday and her father’s as well. It was the Acadian tradition in Colleen’s family to hold marriages on Christmas Eve so that family and friends would have a few work-free days to partake of feasts and plot a really elaborate shivaree. To be the focus of such a celebration amongst people he still didn’t know very well would have been agony for the shy, young Jamie. “When Colleen’s grandfather got married, they tied sleigh-bells to the mattress,” he told me, shuddering at the thought. “We were spared that, thank God.” The couple honeymooned, in part, at the old Reaney farm where Jamie had been able to come to a kind of truce with his stepfather and mother, and then departed for Winnipeg as he resumed another year’s teaching at the University of Manitoba. Housing is always an early trial for newlyweds but their lot was harder than most; compounded by Jamie’s salary of a mere $2,200 a year, the remoteness of his place of employment and the fact that neither of them knew how to drive. Their longest lasting Winnipeg residence was a small house made out of flats in a cheesy little suburb that took a couple more decades to really get going. They weren’t on any bus lines, the terrain was treeless and windswept and though their home was within walking distance of the university, it could be a rather terrible hike. Jamie recalls: “I had to cross a ‘bridge perilous’ which was a plank over a ditch, always coated in ice in the winter, and if you fell in the springtime, then what was waiting for you down below was gumbo. I was going to hear a lecture by Gabrielle Roy and my shoes were literally ripped off my feet by the mud. Finally, I had to go barefoot, carried my shoes around my neck and got changed in a washroom at school.” With a place of their own and not just an apartment, Jamie was finally able to make good on a promise he’d made years earlier and invited his father to live with them in a spare room upstairs. Until the old man’s death in 1976, he would be a daily part of their lives, usually right in their home until his last few years of hospitalization in London. Eccentric (he carried around a tobacco can as his personal spittoon) absent-minded (he would sometimes wander off and have to be brought home by the police) and occasionally irksome (he kept to his own timetable and diet which didn’t make household organization very easy), Colleen learned to cherish the man almost as much as Jamie. Once children started arriving on the scene – James Stewart in 1952, John Andrew in 1954 and Susan Alice Elizabeth in 1959 – mobility became the kind of daily ordeal on which Sisyphus built his legend. Colleen remembers: “It was so cold in the winter and so cut off . . . but I’d made it a point that every day we’d have to at least get out and do something.” The aggy dips had some livestock barns across a field from their house and during afternoon outings with their sleigh, Colleen would herd the children into one of the barns so that everyone could warm up their hands on the sheep. As for the house itself, Jamie takes a perverse delight in listing everything that was wrong with it – the upstairs wasn’t heated, the furnace was undependable, mushrooms grew on the living room ceiling, the septic tank was always in danger of flooding and the basement was so wet that rubber boots were mandatory on washing days. Colleen listens to this catastrophic list and smiles fondly, adding interjections, “Oh, it was a nice house,” “Your father liked a cool room,” “Those were wonderful times”. With these kinds of distractions and disruptions going on all around him (welcome though they were), it is perhaps not so surprising that Jamie wasn’t as completely focused on his writing as he would like to have been. And as Jamie’s personal life went through these adjustments, the larger world was changing as well. He was no longer so sure about where or how his writing was going to fit in. Post-war realism left him decidedly cold. No one seemed to share his enthusiasm for really gothic stories. “For five years, I wrote a novel every summer but they weren’t any good. I didn’t know enough about life and I was still too worried about being original. I had about 100 orange coil notebooks which I’d filled up back on the farm. My mother used to keep throwing them out and I’d find them and bring them back in. I’m still using those for ideas. They’re filled with notes and drawings which could’ve helped me at that time but I was too ashamed to read them.” What enabled Jamie to re-approach that primal material, to worry less about originality and more about origins, was working in Toronto for two years on his Ph.D. thesis under the powerful tutelage of Northrop Frye. In 1957, the very middle of Jamie’s Ph.D. term, Frye published The Anatomy of Criticism in which he first set down his major theories on ‘the grammar of the imagination’ – the underlying principle of symbolism and order behind all literature. Jamie took Frye’s theories completely to heart and now credits Frye with a personal influence on his thought which is second only to that of his father. In 1958 Jamie was awarded his Ph.D. and won his second Governor General’s Award for the Spenser-influenced suite of poems, A Suit of Nettles. As a writer he switched back into the overdrive gear which would be maintained from here on in, only letting up the pace within the last year, not because he was stuck or didn’t know what to do, but because he was dead tired. Jamie returned for two more years of increasing philosophical disagreement with his English department overlords in Winnipeg. He was frankly eager for a change of scene and, when an opening became available at the newly expanded University of Western Ontario in 1960, the family made the move to London and set up shop in the heart of Souwesto, with their two hometowns of St. Thomas and Stratford respectively situated to the immediate south and north. After a brief stay on Craig Street, they moved into their present home within easy walking distance of the university campus. The London art scene of the early 1960s was percolating with new personalities and interests and upon their arrival in town, Colleen and Jamie dove right in, exchanging ideas and hatching projects with Irene and Selwyn Dewdney, Jack Chambers and Greg Curnoe to name but four. This was the brief and golden era of regionalism’s first dawning when a group of talented artists were making it a point to resist the usual drift to Toronto, Montreal or New York and stay put, dig into the virgin soil of Middlesex County and discover the art of this region. Some of it, even then, was hooey. Jamie fondly recalls some of the artists that Greg Curnoe was promoting at the old Region Gallery: “They had the guy who collected cans for ten years and built the Carnation milk can palace. And there was the first Nihilist in town who was a raving madman – he always wore orange pants – and he exhibited the window that his mother was looking through at the very moment she died. It was fabulous! They were encouraging that kind of person.” Jamie’s primary fascination was now with regional stories that were paradigmatic of the great myths and, in order to realize these stories as fully as possible, he was increasingly drawn to writing for the stage. In the mid-60s Jamie started up the Listeners Workshop in the Alpha Centre on Talbot Street where he hosted and sometimes directed the theatrical equivalent of jam sessions. Students would come down, his own kids and their friends and any other interested parties, and some mornings they’d try to work out new scripts which Jamie had just developed. Other times he would nail a list of symbols and images to a post in the middle of the floor; they’d take each idea in turn and try to act it out. There was usually a pianist and a drummer on hand – sometimes James Stewart brought down his guitar – and tables filled with possible props, cardboard tubes, stackable boxes, rolls of material, a garden hose. A lot of Jamie’s plays from the last 20 years grew out of those workshops. Jamie speculated that, “If we’d stayed in Winnipeg, I suspect my trilogy would’ve been on Louis Riel. But here, that wasn’t what needed to be written. Here, it had to be the Donnellys.” It was at about this time that Jamie began the ten long years of researching, workshopping, rewriting and refining what would emerge in the mid-70s as the Donnelly trilogy – the major opus of his career. In 1966 Jamie and Colleen’s middle child, John Andrew Reaney, suddenly died at the age of twelve from an undetected attack of viral meningitis. His younger sister Susan was seven years old at the time and remembers: “He didn’t seem sick at all. Everybody thought he had the flu and he was being kept in his bedroom but he’d still come to dinner and tease and torment me just like usual. So you can imagine the surprise when he went into a coma. Mom couldn’t wake him and that’s when they called the ambulance. He was hospitalized but I wasn’t allowed to see him because I was just a child. They took me around outside the hospital and pointed out his window. It was so sudden. The whole thing took about a week.” The family was devastated and Susan remembers months of time spent living on eggshells in the wake of John’s death. One night, doing the dishes all alone and putting them away, she piled books on top of a chair, climbed up and stretched tall on precarious tiptoes, straining to reach the highest shelf . . . all because she couldn’t bring herself to ask for help, didn’t dare disturb the silence and sorrow which hung over the house like a fog. She remembers, “It was very hard for my mother because when your child dies, everybody feels so sorry for you and they think they have to come and visit you every minute of the day. I came home from school one day to find half a dozen of her friends had all descended on her. She was feeling horrible anyway but here she had to run around getting them coffee and being polite. I just stood in the doorway and glared at them, thinking, ‘are you all nuts? Can’t you see that she’s tired?’ And then as they were finally leaving, one of them took me aside and said, ‘I think your mother needs a rest.’ Give me a break.” James Stewart was thirteen at the time of John’s death, enduring the self-conscious agony of starting high school after years of isolation in advancement classes, and John had always been his steadiest companion. It was only ten years ago that Susan could get James to talk about John’s death at all and James admits that, “After my brother died, there wasn’t much that I remembered about my childhood and I’m sure that’s why. Even now, if I think really hard I can start to remember but I still don’t push it.” Jamie and Colleen now mention John often in the course of their reminiscence and the speaking of his name isn’t especially charged or hushed. His books and pictures and records are still part of the household (except for the Chipmunk album Jamie broke over his knee one Christmas morning after ten consecutive playings), and Jamie has kept all John’s compositions and the scripts he used to write for his theatre in the basement. Something I was very impressed and moved to discover was that the year after John’s death, Jamie worked with all the kids in what would have been John’s grade eight class to put on the first production of his children’s play, Geography Match, at Broughdale Public School. Such was the impact of the Donnelly trilogy that there probably isn’t a whole lot more that needs to be said right here. The trilogy which was completed in 1975 was appraised by Ross Woodman in The Globe & Mail as, “The best Canadian play yet written . . . among the best poetic dramas ever written." It seems strange and yet perhaps typically Canadian that none of Jamie’s Governor General’s Awards were given for either the entirety or any part of what is his most famous work. The St. Nicholas Hotel did, however, win the Chalmers Award in 1975 and at the official ceremony, the MC, Herb Whittaker, pulled a uniquely humiliating gaffe by reversing the order of the winner and the runner-up, thus announcing that the winner in the playwright category was Rick Salutin. In his acceptance speech, Salutin thanked most of the universe for the honour and magnanimously donated the full cash prize of $5,000 to the charity of his choice. Then came the correction, much clearing of throats and nervous laughter, and everyone watched intently to see whether Jamie would uphold Salutin’s commendable gesture or stuff the money in his pocket. Jamie stuffed the money in his pocket. Around this time as Jamie’s fame was reaching its highest crest, Coach House Press in Toronto quietly published Colleen’s second book of collected poems, My Granddaughters Are Combing Out Their Long Hair. There has been another collection published since then and Colleen now finds herself in the pleasant situation of writing poems only when publishers ask her for some and is going out on reading tours with steadily increasing frequency. Perhaps reacting against the flamboyance and high profiles of their parents, James Stewart and his sister, Susan, seem to be a quieter generation. From all accounts, John was the only real mixer of the lot. Susan at 28 still feels she has a couple of years to locate and slide into the perfect career slot. In all likelihood it’s going to have something to do with the invisible side of publishing. She’s been a freelance proof reader for various Toronto publishers, has taken courses in magazine editing and publishing and currently feels particularly drawn to the job of photo-researcher. James admits that in choosing journalism for his career, he very carefully steered himself clear of any literary pursuits that might seem to put him in the position of competing with his parents. But there is hope that the Reaney clan may yet produce another burst of billowing imagination for the world. James’ wife, Susan Wallace, tells a most heartening story of their five year-old daughter, Elizabeth: “I’ve always consciously tried to be as normal as possible for Elizabeth; I think children need that kind of predictable stability. Today I took her to her music lesson and we were ten minutes late. Do you know what she told her teacher? She said, ‘I’m sorry we’re late, we had a little trouble adopting the baby.’ Where’d she get that from? I couldn’t believe it but I think she’s Colleen. She’s got the build, the walk and everything. I think she’s Colleen all over again.”

3 Comments

Patricia Black

26/6/2019 08:08:06 pm

I didn’t see this in the original, Herman. It was forwarded to me by Susan Mersey.

Reply

Max Lucchesi

28/6/2019 01:16:21 am

Hello again Herman. You write lightly and affectionately about the town you obviously love, populated by the many fine people you admire. A town founded by American Loyalists fleeing the founding of America, in order to remain loyal to their German king. After trekking northwards through Cherry Valley to the forests of Southern Ontario they built a city. A city to mirror the capital of an empire complete with it's name and it's Thames The conservative DNA of it's founders was trowelled into the town's foundations together with the bricks and mortar. It has remained there ever since. As a Catholic you bemoan prejudice towards Catholicism and as an admirer of Reaney's work you wonder why the Donnelly trilogy was not feted as it should have been and only staged in a workshop. The founding fathers brought their anti Catholicism with them, it was re-enforced by later immigrant Scottish Orangemen whose Lodges in Canada still flourish.

Reply

David Warren

20/8/2019 09:22:41 pm

What a wonderful old piece of "Jamie"; worth the hassle of time-travel (passing through chronological customs, declaring one's anachronisms, &c).

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed