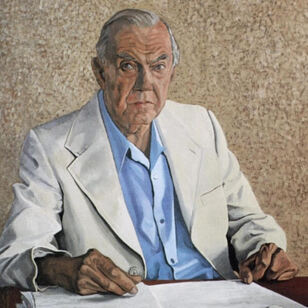

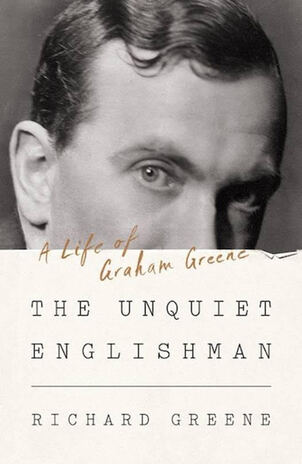

Graham Greene (1904 – 91) Graham Greene (1904 – 91) LONDON, ONTARIO – Though I received it for my birthday way back in May, I’ve dawdled a good few months in taking up The Unquiet Englishman: A Life of Graham Greene (W.W. Norton, 2021) by University of Toronto English prof (and no relation, as they say) Richard Greene. And I now am delighted to report that Richard Greene does the best job I’ve yet seen of frankly and sympathetically exploring not just the life and career but the maddening fissure of constitutional disloyalty that ran right down the centre of Graham Greene’s personality and made his life such a trial for himself and virtually everyone who tried to love him. One of the real giants of twentieth century fiction whose career spanned sixty wildly productive years – and who seemed a shoo-in for but never did win the Nobel Prize – it might seem odd that it has taken this long for a worthy biography to appear. But that was just the way that Graham Greene (1904–91) wanted it. Greene himself turned out a couple slender volumes of cagey, very partial and occasionally misleading memoirs in his day. And to discourage any competent biographers from rising to the challenge of chronicling his life, in 1974 Greene appointed a touchy and fussy academic named Norman Sherry to write the ‘authorized’ biography. What seemed such a plum assignment turned out to be a real challenge to Sherry’s mental health as he punctiliously slaved away for thirty years on a bloated opus which garnered less and less interest as its three fat volumes appeared from 1989 to 2004. The only other contender for a major biography, was a single-volume job (The Man Within, heavily focusing on Greene’s scandals) that was published around the same time as Sherry’s second volume (and stole some of that project’s thunder) by the almost equally undistinguished Michael Shelden who had just come off the production of the deeply snoozy ‘authorized’ bio of George Orwell. (On her deathbed, Orwell’s widow, Sonya, had assigned that job to Shelden for much the same reason as Greene anointed Sherry; to ensure that its subject’s life was smothered rather than explored.) So, one inert triple-decker that tediously combed through every last thing that Greene wrote or said or did and one slightly hysterical scandal sheet full of subterfuge, dysfunction and bed-hopping with an occasional literary interlude. A full three decades after Graham Greene’s death, the world was more than ready for this insightful and even-handed appraisal, clocking in at five hundred pages, of one of the most popular and influential authors of the twentieth century. Richard Greene turns sixty this year, has been enthusiastically reading his elder namesake since he was a teenager and developed a good grasp of his subject’s long life by compiling and editing a highly regarded collection of Graham Greene’s letters; many of them only recently surfaced. A single-sentence distillation of what I admire in this biographer’s sure-footed approach can be found on page 117 where he forthrightly notes, “Greene went on to Mexico City, where, in a characteristic pairing, he made visits to a monastery and to a brothel.” In taking my sweet time in getting around to reading this biography, I’m adhering to the same cautious stance I’ve always maintained towards Graham Greene. I’ve read his canon sparingly over the years – seven titles by my reckoning (The Power and the Glory, The Heart of the Matter, The End of the Affair, A Burnt Out Case, Travels with my Aunt, Ways of Escape, Articles of Faith) – and while always finding them gripping and full of admirable qualities, I have set aside each book feeling a little besmirched by the seediness of the tale and in no hurry to re-immerse myself in the characteristically dank atmosphere of Greeneland. Despite the thematic depths, rich insights and shrewd observations that distinguish all of Greene’s writing, that negative charge emanating from every one of his books has prevented me from doing him the disservice which I’ve regretted with other writers; of racing through an entire oeuvre in rapid succession and thereby depleting the impact of the stories. Virtually every one of Greene’s tales comes with a nasty sting; a little something to dash expectations, curdle the heart and annihilate hope. I sometimes regard him as the anti-O. Henry, instead of contriving any sort of positive or at least compensatory resolutions, Greene's fiendishly inventive stories are typically derailed in the home stretch by sudden deflations and betrayals and ironic anti-climaxes. Early on Greene was a canny and even recklessly courageous film critic. A sophisticated New Yorker-type magazine he co-edited called Night and Day was sued into non-existence when his withering review of Wee Willie Winkie accused child star Shirley Temple of “dimpled depravity” that was designed for the titillation of “middle-aged clergymen”. (It was an outrageous thing to say but he had a point, damn it.) With their minimal expositional build-up and quick inter-cutting between scenes, there is a cinematic quality to Greene’s novels which makes them easy to digest and most of his books have been successfully filmed. I would particularly call your attention to two of the earliest Greene adaptations, The Fallen Idol and The Third Man, which hold up more than seventy years after they were made as first-rate entertainments. Graham Greene could be wonderfully generous to people he scarcely knew such as Scottish novelist Muriel Spark whose early career he subsidized with a desperately needed monthly stipend which always faithfully turned up at her flat along with a case of red wine so as to take the cold edge off of charity. But he was at war with himself in a fundamental way for most of his life and could also be chillingly indifferent to the well-being of people who had more primary claims on his concern . His first identity crisis erupted while attending St. John’s School in Berkhamsted north of London where his father was headmaster. A green baize door separated the world of his family from the world of his peers and on either side of that door, a very young Graham Greene was already suffering under the strain of acting as a double agent. His father expected him to be a model student and also to serve as a spy and a snitch. His friends expected him to join in their acts of rebellion and ridicule against their overbearing headmaster. Unable to completely align himself with the people he found at home or at school, Greene felt like a traitor and a fraud. In his own review of The Unquiet Englishman for The Catholic Register, Ian Hunter writes, “Forty years later, when he went back to St. John’s School to gather material for a projected novel, Greene found his memories so debilitating that he abandoned the project and went off instead to a leper colony in the Congo, the setting for A Burnt Out Case. It was his wretched school days that provided twin themes – betrayal and the hunted man – which would resonate through his later fiction.” Throughout his life Greene suffered from manic depression and travelled ceaselessly to one troubled hot-spot after another to gather material for his books and to distract himself from the chaos and disappointment that riddled his personal life. During a couple of his most extreme psychological crises he even played Russian roulette to keep boredom at bay and to trick himself, at least temporarily, into valuing life more by almost losing it altogether. Incapable of fidelity to his wife or the Catholic Church which he joined at the age of 22 so that he could marry her, duplicity became the reigning theme of both his personal and literary life. In the ‘40s he was recruited into the British spy agency MI6 where he befriended the notorious traitor Kim Philby and continued to stand by him even when the worst of his betrayals became known. Asked once to select an epigraph that described what drew him as a writer, he chose this from Bishop Blougram’s Apology by Robert Browning: “Our interest’s on the dangerous edge of things, The honest thief, the tender murderer, The superstitious atheist.” His cousin Barbara was a fully trained nurse and probably saved Greene’s life when he fell victim to exotic fevers while she accompanied him on his fact-gathering trip through Sierra Leone and Liberia in 1935; an excursion which was recalled in Journey without Maps. “His brain frightened me,” she wrote in her journal. “It was sharp and clear and cruel. I admired him for being unsentimental, but ‘always remember to rely on yourself,’ I noted. If you are in a sticky place he will be so interested in noting your reactions that he will probably forget to rescue you... Apart from three or four people he was really fond of, I felt that the rest of humanity was to him like a heap of insects that he liked to examine as a scientist might examine his specimens, coldly and clearly. He was always polite. He had a remarkable sense of humour and held few things too sacred to be laughed at.”  I find it reassuring that even in an appraisal as disturbing as that one, Greene’s cousin can still commend his sense of humour. And The Unquiet Englishman is packed with many examples of his humour which I find wonderfully humanizing. I particularly enjoyed this joke which – while rather cruel – seemed to be aimed equally at himself: “His practical jokes included from time to time ringing up a retired solicitor in Golders Green who happened also to be named Graham Greene and berating him, in various accents, for writing ‘these filthy novels’.” Constantly contriving research junkets that would take him away for weeks and months at a stretch, Greene was unfaithful to his wife with whores and mistresses from early on in his marriage. And he was even more comprehensively absent to his two children that he never wanted to have in the first place; though he checked in with them from time to time and helped them out financially when they were older. Malcolm Muggeridge, who appears with some frequency in this biography as a uniquely astute commentator, noted Greene’s relief when the Luftwaffe delivered a bomb that finally allowed him to move out of the family home for good. “Soon after his house on Clapham Common had been totally demolished in the Blitz, I happened to run into him . . . and he gave an impression of being well content with its disappearance. Now, at last, he seemed to be saying, he was homeless, de facto as well as de jure.” The author notes that Graham Greene functioned best as a writer when he was at loose ends, holed up on his own in a rented room somewhere and keeping to his own eccentric schedule without concern for accommodating the needs or expectations of anyone else: “He distrusted the veneers of a comfortable life and felt that reality was only knowable under conditions of privation. His quest for absolutes required such conditions.” I’m prepared to believe Graham Greene when he says that he hated being referred to as a "Catholic novelist" if only because he seemed to quite sincerely hate so many things about himself; most particularly his inconstancy as a lover and a believer. Running hot and cold about his adopted faith and always ready to express doubts and misgivings about the veracity of any of it, he was just the kind of Catholic that lefty journalists love to interview and quote. Noting Greene’s inconstancy as a believer, Malcolm Muggeridge opined, “Spiritually, and even physically, Graham is one of nature’s displaced persons – a saint trying unsuccessfully to be a sinner”. In his very best work – and here I would say the nod goes to 1940’s The Power and the Glory about a whiskey priest who vindicates his failed calling by one final act of barely recognized heroism – I would almost agree with Catholic Thing editor, Robert Royal, who regards Greene as “the premier English novelist of the soul.” Though I would actually place Evelyn Waugh and Robert Hugh Benson a notch above Greene in their gift for giving literary shape to the invisible contours of faith, Greene certainly did have a knack in the first half of his career for working deeply intriguing religious themes into his novels. At his worst – hobnobbing with Communist dictators and blandly overlooking their atrocities while taking fatuous swipes at American imperialism; sucking up to priests with political agendas while crapping on John Paul II for his intransigence regarding birth control and the South American predilection for a politicized Catholicism known as ‘Liberation Theology’ – Graham Greene became about as tiresome a spokesman for the Church as Fr. James Martin is today. It's interesting to speculate how he would have regarded the papacy of Francis. The indispensable Ralph McInerny bitingly notes that later in life as his leftward drift increased, Graham Greene was routinely exercising “a preferential option for the Reds” and had become a much less interesting writer because he was no longer so open to so many facets of life and reality. Eventually his faith became so loosey-goosey that Greene could look back on his conversion and write unintelligible hooey like this: “I can only remember that in January 1926 I became convinced of the probable existence of something we call God, though now I dislike the word with all its anthropomorphic associations and prefer Teilhard de Chardin’s ‘Noosphere’.” Ah, yes, nearer my Noosphere to Thee. If he sometimes seemed to become a parody of himself during this less spiritually robust period of his life and career, it has to be admitted that nobody did a better impersonation of Graham Greene than Graham Greene himself. Indeed, he had the trophy to prove it. Greene actually won a prize in the 1970s when he submitted an entry under a fake name for the best send-up of Graham Greene's prose in a contest that was run by The New Statesman. And, constant in his inconstancy to the very end, just before he died Greene did insist on receiving the last rites of the Church from which he'd so frequently and publicly distanced himself. And there among his effects was found the picture of Padre Pio which he kept in his wallet until the very end; a picture he acquired after attending a Mass in 1949 at which the stigmatic priest, now a saint, presided. Greene had been mesmerized by the evident sanctity of the man during that two hour Mass – the Padre occasionally tugging his sleeves to cover the wounds on his hands – and said that the experience “introduced a doubt in my disbelief”. This pitch-perfect biographer concludes his account of that saintly encounter with a gem of an observation that I’m sure would’ve made his subject smile: “Greene regarded most atheists as far too sure of themselves.”

3 Comments

Ninian Mellamphy

16/11/2021 10:14:49 am

Well done, Herman. You have successfully persuaded me to read THE UNQUIET ENGLISHMAN, even though I have not read a word by Greene since the day he died.

Reply

Max Lucchesi

17/11/2021 12:05:40 am

Excellent piece, Herman. If you do intend to read more of Greene's work, don't start with Brighton Rock. Pinkie's sheer nastiness will make you shiver. A good summary of a prolifically talented but deeply unpleasant man. Glad you mentioned Malcolm; he was always worth listening to. A couple of quibbles though. Contraception was always a Catholic hypocrisy. Any knowledge of the Monroe Doctrine of 1825 will give you an insight into America's ruthless exploitation of South and Central America. And lastly, no one who has not lived and worked there has any business having an opinion on Liberation Theology.

Reply

Jim Ross

24/11/2021 01:37:36 pm

My high school literature teachers must be credited with assigning Graham Greene to us in grade 12: Brighton Rock, and A Burnt Out Case. Probably not allowed today.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed