LONDON, ONTARIO – In Noel Coward's Private Lives, divorced lovers Elyot and Amanda, have unknowingly booked themselves into adjoining honeymoon suites at the same French hotel, and meet each other when they're driven out onto their respective balconies to get away from tiffs with their latest spouses. To make matters worse, the hotel orchestra in the plaza below insists on playing and replaying the popular tune which Elyot and Amanda had once appropriated as "our song". When the tune is going around for the third consecutive time, they glance at each other in awkward embarrassment and laugh. "Nasty insistent little tune," says Elyot, to which Amanda opines: "Extraordinary how potent cheap music is." I frequently tumble those lines in my cranium while marveling at the uncanny hold that a whole slew of disposable pop music ditties still asserts on my affections, even though I'm supposed to be a senior citizen now. Yes, I've moved on from such piffling, transitory fare - to classical music, for the most part - and can intelligently discuss the merits of contrapuntal structure in J.S. Bach, polyphonic harmony in Thomas Tallis, and Claude Debussy's never-ending quest for the "sonorous halo". But play me some three-minute barbarian freak-out by The Bubble Puppy or some exquisite pop bauble by The Small Faces and – terribly sorry – but I have no choice except to succumb to drooling, raving ecstasy. Will it ever be thus? Yeh, looks as if. I remember twenty years ago this summer when I was halfway through Eugenio Corti's, The Red Horse, a magnificent, 1,000 page novel that had just been translated into English, exploring the lurching political travails of twentieth century Italy. It was one of those books that makes you cheer when a lunch or meeting falls through, because you know you'll be able to give it another hour or two of your attention. And then I happened upon a second hand copy of Tim Riley's, Tell Me Why - which offered a track by track analysis of every recording made by The Beatles (together or solo) up until 1988 - and The Red Horse was set aside for a day as I devoured Riley's book in one greedy gulp. Gosh, who knew I had that kind of time to spare? I already knew most of what Riley had to say but his book confirmed a lot of my judgements and it was great to enjoy a full-immersion wallow in that uniquely rich body of music which carried so many fond memories and auguries of hope for an entire generation. Grow beyond it as we hopefully do, the music we enjoy in our adolescence always retains an immediate access to our innermost depths that no other art form even approaches. And even then I also knew that I was at least partially driven into the arms of musical nostalgia by the curt and vague reports circulating that week about George Harrison's smooth recuperation from cancer surgery. Always the Beatle with the strongest aversion to allowing fans into every facet of his life, I feared that our George might be fixing to die and, as usual, was just telling us to buzz off and leave him to it; to – in the words of the very first Harrisong the Beatles ever recorded, “go away, don’t bother me”. And then about six months later – and twenty years ago this week, in the still reverberating wake of the 9/11 attacks which somewhat muffled its impact – my hunch was confirmed correct. George was just telling us to give him some space and let him die in peace. The assassination of John Lennon twenty-one years earlier was more shattering than Harrison’s death. But when such a beloved figurehead of an entire generation’s youth dies of natural causes, one does feel mortality’s cold wind at the back of one’s neck in a new and personal way. One minute George is immortalized in the public imagination as this shy but cheeky Adonis-figure, sharing a microphone with Paul McCartney and making millions of girls shriek whenever he shakes his hair and sings. And the next minute he’s battling cancer in his lungs, his throat and his brain, and is only six years shy of that impossibly distant dotage which he and his band-mates once mocked in their jaunty little ditty, When I’m Sixty-four. In the wake of George Harrison’s death I suspect ours was not the only household feeding A Hard Day’s Night into the maw of the VCR for a poignant re-immersion into our own musical awakening. Quickly shot in black and white on a very tight budget, the Beatles first feature film still remains the primary document for understanding this band and the enormous cultural and sociological impact they had on the post-war world. The rapid-fire delivery of the dialogue, the quick inter-cutting of the camera shots and even the scenes themselves – many built on nothing more than throwaway jokes – were revolutionary in their time and challenged the audience to attend closely or risk missing out on the fun. There had been music-driven crazes and fads before, but nothing so simultaneously charming and subversive as this. From the opening shot of three Beatles being chased by a mob of girls down a narrow alleyway into a London train station, it’s clear this is not going to be just another sappy pop star’s film. Five seconds into that sequence George takes a very real tumble and goes sprawling onto the sidewalk, scrambling to pick himself up. Leading the whole pack, John Lennon looks back at his fallen mate and can’t help laughing in sadistic delight. There’s a grittiness and witty irreverence here, a comic spoofing of the surreal absurdities of their own celebrity that earlier and more conventional pop stars like Frank Sinatra or Elvis Presley never approached in their films. George was also featured in that movie’s single most prescient scene, warning of the sort of relentless and sophisticated commercial manipulation that would keep the gears of the music biz spinning in the years ahead. George has accidentally wandered into the ad agency which represents a clothing manufacturer out to corner the teenage market with white turtleneck shirts that look suspiciously like the stage gear worn by the Beatles’ 1964 musical rivals, the Dave Clark Five. George is mistaken for a young actor booked to recite lines about how fab and gear these shirts are. Instead, he unhinges the smug certainties of these cynical marketers by rejecting the shirts as “dead grotty” – Liverpudlian slang for ‘grotesque’. “It’s rather touching, really,” the ad director sneers with withering contempt. “Here’s this kid trying to give me his utterly valueless opinion when I know for a fact within four weeks he’ll be suffering from a violent inferiority complex and loss of status because he isn’t wearing one of these nasty things. Of course they’re grotty, you wretched nit, that’s why they were designed, but that’s what you’ll want.” A sturdily independent soul all along, George was the happiest to step off the merry-go-round of Beatlemania in 1970 and steadfastly refused all enticements to get back on. Of our four ambassadors of musical bliss, such was George’s fabled quietness, patience and cool detachment, that he was always the easiest one to imagine as a senior citizen. Dead at 58, we thought to ourselves in 2001, “He was robbed.” What fun it would have been to see him in his eighties, with a blanket spread over his knees, sitting under a tree in the manicured garden at his Friar’s Park estate, reflecting on that long-passed era (as he phrased it in one of his more winsome solo songs), “back when we was fab.”

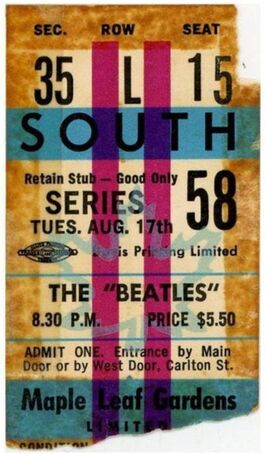

And now, twenty years after that sad milestone, I often find myself thinking about George and the rest of The Beatles in relation to a girl I will only identify as Laurie D. (1952 – 65) who regularly turns up in my own litany of prayers for the dead. We were never what could be called close but I went to school with Laurie from kindergarten to grade seven and she was the very first of my contemporaries to die. She was what we called a blue baby, thanks to a congenital heart defect that caused insufficiently oxygenated blood to pass directly from the right side of the heart to the left, resulting in cyanosis which gave her skin a bluish tinge. She never had the stamina of other kids and would easily run out of breath, sometimes resulting in a low, bronchial sounding cough. And when the weather got really cold, she wouldn’t be allowed outside for recess at all as she’d soon succumb to a shuddering case of the shivers that would wrack her entire body. I frequently recall an incident that must’ve taken place when we were in grade two or three when our entire class had just received shots for polio or smallpox or something like that. When one of us jostled up against Laurie a couple hours later, pressing against her affected arm – and I’m thinking it might have been me if only because I remember the incident with such remorse – she erupted into major and extravagant tears. “As if her life isn’t difficult enough, already,” I remember thinking. There was a surgical procedure that had been developed for blue babies that was still pretty risky circa 1965. If you came through – and I seem to recall hearing that the odds were about fifty/fifty – you had a good shot at a full and healthy life. I don’t think any of us knew Laurie was going in for the surgery in the summer after grade seven. But back at school on the first day of grade eight, we learned that she hadn’t made it. And we also learned that she had been buried with her ticket to see The Beatles on Tuesday, August 17, at Maple Leaf Gardens. Those tickets were $5.50 apiece. There were two shows at 4:00 and 8:30 p.m., each one drawing 18,000 (or 17,999) fans. You could say that Laurie’s death coincided with the close of the first gloriously giddy rush of Beatles acclaim. Yes, their impact on the world had already been immense but if they hadn’t progressed beyond the band that Laurie and I loved in her final summer, I wonder if I would still feel drawn to regularly spin their platters today for the sake of a little spiritual revivification. The Beatles went into the studio that October after their North American tour wrapped up and spent the next six weeks crafting what I consider to be their first real album. Released the first week in December that year, Rubber Soul was something much more nuanced and sophisticated and boldly exploratory than just another collection of recently cobbled together tracks. It was a beguiling harbinger of the more evocative delights to come that I’m sorry Laurie D. never got to hear.

1 Comment

Max Lucchesi

2/12/2021 12:38:54 pm

Oh dear Herman, after your intro I expected you to tell us the songs of your life. Instead you give us a personal Beatles fanzine. I'd hoped for secrets like in 1961 I bought a Mose Allison EP and am still singing 'I love the life I live or Ask me nice'. Or for one crazy summer you followed your favourite band accross Canada, like I did in the summer of 64 for my mate Booker Irvine when he was playing sax in Nedly Elstak's quintet. The Blue Note in Amsterdam, the Domicile in Munich or the Vingarten in Copenhaven, they would break into 'Fly me to the moon' for me. Didn't you ever hold hands and smooch to ' I got you babe'? Yup, songs live in our heads whether we like it or not. As Brian Ferry sang, " They are playing oh yeah on the radio". Still, long, long ago. Hopefully you're not still listening to Plain Chant. Never mind the contrapuntal, how are you with Bel Canto and Coloratura? Nice essay even though I was never a great Beatles fan.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed