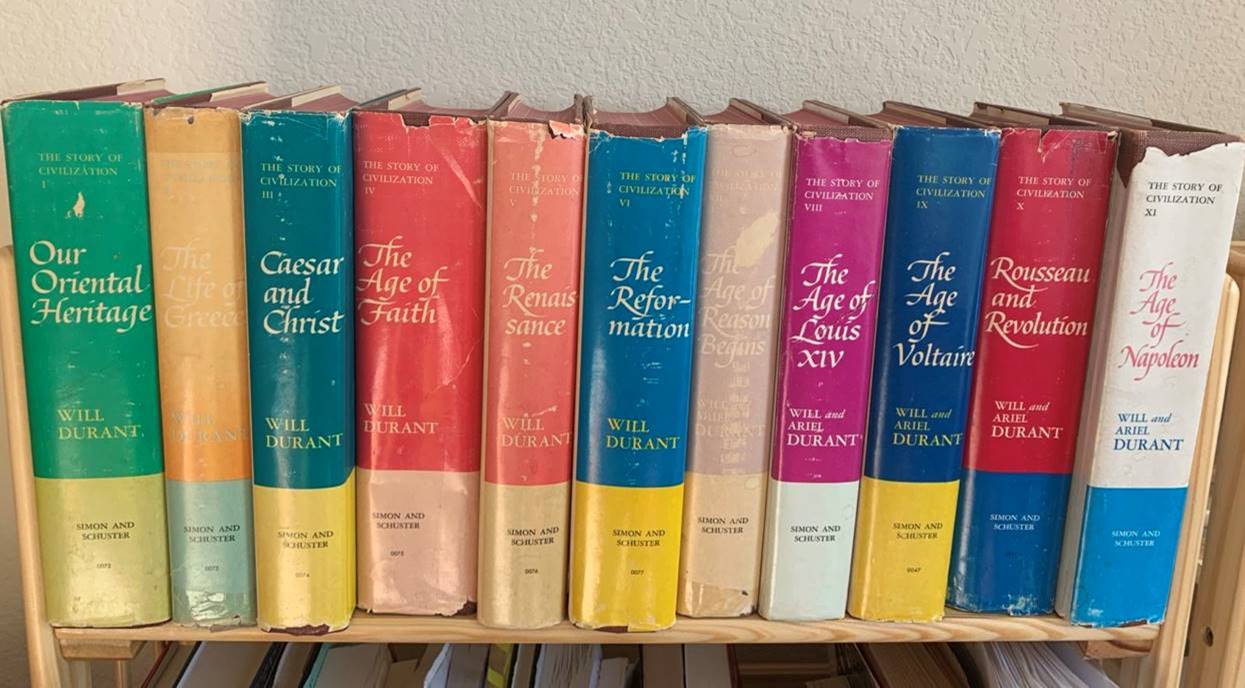

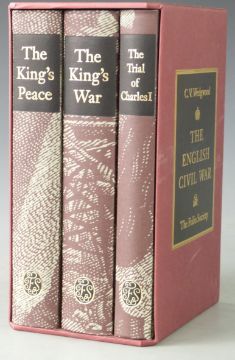

ARIEL and WILL DURANT ARIEL and WILL DURANT LONDON, ONTARIO – Those of us susceptible to come-ons from book and record clubs always remember with a pang of nostalgia and lower back pain, the greatest, heaviest and bulkiest membership offer the Book-of-the-Month Club ever made. As luck would have it, I wasn’t in that afternoon in the fall of 1978 when the postal delivery truck tried to drop by all eleven volumes of Will and Ariel Durant’s The Story of Civilization – 10,000 history-packed pages covering six millennia from Our Oriental Heritage to The Age of Napoleon. So a little card was left in the mailbox instructing me to pick up this great literary motherlode myself at the old central post office in the main floor of the Dominion Building on Richmond Street at Queens. It doesn’t matter what time of the year it happens, there’s always something giddy-making about the prospect of receiving a package in the mail – particularly one that contains seventy-three and a half pounds worth of books. There was still about fifteen minutes until the post office closed for the day and I had no intention of deferring this Christmassy pleasure to the next day. Not even glancing at the rain clouds gathering overhead, I raced across the Queens Avenue bridge on foot, arriving at the appropriate wicket to take ownership of my membership premium just in the nick of time. Short minutes later I was swept out onto the post office’s front steps and the door was locked behind me, the lights were switched off and the rain began to spit. At my feet were two of the heaviest boxes I’ve ever lifted in my life. I couldn’t carry both for any distance so the only thing for it was to run forward with one box and set it down, come back for the other and take it farther forward yet, come back for the first one and advance it farther . . . and so on and so on . . . like a one-man, two-box, leapfrogging team. Luckily the full and drenching rain held off until I got home and I was able to unpack the books, undamaged and undampened, from their decidedly moist cardboard boxes. I read through five of the volumes that first year and have had many subsequent occasions to go dipping and digging through all of them over the succeeding forty-two years, whenever I need some background or details for other reading or writing or, back in the day, when helping our kids research their homework assignments. I’ve rarely scanned their indexes for a subject or a historical personage in vain and regardless of the era or the culture under consideration, I find their accounts comprehensive and their judgements generous and fair. The sheer scope of the Durants’ industry is boggling as they trace human civilization from its first stirrings in the East and up to the end of the Napoleonic wars. They devoted forty years of their lives to this one great project, winning a Pulitzer Prize for the tenth volume, Rousseau and Revolution, and only completing the eleventh volume three years before I took possession of the set. Will Durant was a one-time seminary student who lost his faith when he started reading philosophy and science, most particularly Baruch Spinoza’s Ethics Demonstrated in Geometrical Order. Yet the collapse of his own adherence to the Christian creed didn’t make him bitter or fill him with contempt for the Church or religion. On the contrary, to the very end of his life, he maintained that the study of religion “sheds more light upon the nature and possibilities of man and government than the study of almost any other subject or institution open to human inquiry.” It is common for academics and specialists to sneer at the Durants today for what we could alliteratively call their preoccupation with posthumous, pale-skinned penis people. The Durants never claimed to have crammed every last facet and factor of human history into their saga and never derided the work of specialists or chroniclers who toiled in more obscure or arcane fields. But they did think it was important that each generation should also have historians who weren’t afraid to tackle as long a view of the whole human picture as they possibly could. In A Dual Autobiography (which he and Ariel wrote in 1977), Durant recounted his grand scheme in undertaking what he originally envisioned as a five-volume study of world history: “I had expounded the idea in 1917 in a paper . . . On the Writing of History . . . Its thesis: whereas economic life, politics, religion, morals and manners, science, philosophy, literature, and art had all moved contemporaneously, and in mutual influence, in each epoch of each civilization, historians had recorded each aspect in almost complete separation from the rest. . . . So I cried, “Hold, enough!” to what I later termed “shredded history,” and called for an “integral history” in which all the phases of human activity would be presented in one complex narrative, in one developing, moving, picture. I did not, of course, propose a cloture on lineal and vertical history (tracing the course of one element in civilization), nor on brochure history (reporting original research on some limited subject or event), but I thought that these had been overdone, and that the education of mankind required a new type of historian—not quite like Gibbon, or Macaulay, or Ranke, who had given nearly all their attention to politics, religion, and war, but rather like Voltaire, who, in his Siècle de Louis XIV and his Essai sur les moeurs, had occasionally left the court, the church, and the camp to consider and record morals, literature, philosophy, and art.”  Both Durants died in March of 1981; he at the age of 96 and she at 82. She was originally his student at a sort of quasi-Communist free school and when he recognized that they were falling in love, he resigned that post so as to avoid scandal. They’d been wed, believe it or not, in 1913 when Will was twenty-eight and Ariel was fifteen. She required a note from her parents to get hitched and roller-skated to their city hall ceremony; a form of locomotion, we are told, which was more reflective of her unbridled free spirit than her immaturity. The marriage had a rocky first few years with Ariel taking off twice out of sheer boredom with her husband’s dedication to his literary work. But she always returned to him and was gradually drawn in to assist him, eventually becoming so indispensable to that work that her name was joined with his as a co-author of their books. Starting to feel his age, Will was prepared to call it a day after the tenth volume of their Story of Civilization, until Ariel stepped up and led the charge in producing their final volume on The Age of Napoleon which probably should have been credited to Ariel and Will Durant. Touchingly, they died within days of one another. Ariel became so distraught when Will went into the hospital that she stopped eating, hastening her own demise. Though the family tried to keep Will from finding out about Ariel’s death as he supposedly recovered, he caught wind of the bitter truth on an overheard newscast and immediately went into his own precipitous and final decline. Though her scope was not so universal, another prolific and once-popular historian who is subjected to the disdain of her academically-affiliated ‘betters’ today is C.V. Wedgewood whose best-known work is her three volume history of England’s Great Rebellion (The King’s Peace, The King’s War and The Trial of Charles I) which recounts that little set-to with the Roundheads which ultimately cost poor King Charles his throne and his head. First published in the 1950’s, there is a compelling sweep to Wedgewood’s prose that brings the England of 350 years ago to life. Like a novelist, she catches you up in her gripping, character-driven portrayal of a society which is powerless to prevent its violent dissolution as the royalist and parliamentarian factions have at each other.  Her authorial bio notes that Wedgewood was an “independent historian who combined a facility for synthesizing vast amounts of factual material with an eminently readable writing style.” And hers is just the kind of engaging historical writing that nobody is encouraged to produce anymore and which cannot be trusted anyway – or so we’re instructed by academics and specialists of the post-modernist persuasion who are forever on the lookout for acts of cultural appropriation or Western boosterism. We are told to be suspicious of any historian who presents us with a coherent worldview. Any writer who offers up more than disconnected shards of historical experience, who attempts to assemble a complete and multifaceted picture, is guilty of imposing their own cultural bias on the material. We\re told that such writers are propagandists and liars and that it’s wrong to trace meaningful connections or pose contrasting values between disparate periods and peoples. She may have been female but Wedgewood is now dismissed as one more proponent in that discredited movement of popularisation that followed the publication of H.G. Wells’ The Outline of History in 1920. The spectacular success of Wells’ audaciously ambitious study led to further ‘outline’ volumes like Will Durant’s first big success The Story of Philosophy (1926) and over-arching histories of literature by folks like John Macy and John Cowper Powys. Hendrik Willem Van Loon wrote and illustrated idiosyncratic surveys of geography, history and the arts. Though he was probably the most superficial of the popularisers, I still treasure two of Van Loon’s books precisely for the unintimidated lightness of his touch, though I’m careful to keep them filed away on a lower shelf under ‘guilty pleasures’. New styles in book reviewing also appeared in the 20s and 30s. The approval of certain influential critics virtually guaranteed an author’s success. Anyone who haunts used book shops will have sifted through the flotsam of this movement. Columnists like Christopher Morley and Alexander Woollcott wrote almost exclusively about books, guiding and shaping the tastes of huge, international readerships. Morley and Clifton Fadiman also helped found the Book-of-the-Month Club which moved some 70 million volumes during the depths of the Great Depression. Woollcott was a bit of a blowhard (he loved James Hilton’s Goodbye Mr. Chips in a most unseemly way) but Morley had real acumen and wit and his numerous essay collections can still impart delight and instruction to this reader at least. Van Wyck Brooks’ Makers and Finders was a beautifully written history of the writer in America, from the Declaration of Independence to the end of the First World War. Through five linked volumes, Brooks traced the development of a national literature from its crude, isolated and derivative beginnings to the thriving, multi-faceted scene which F. Scott Fitzgerald inherited. I would single out J.B. Priestley’s Literature and Western Man from 1960 as the last great monument of what is sniffily dismissed today as ‘middlebrow culture’. It is an intelligent, non-academic survey, spanning centuries, continents and cultures, of one omnivorously curious man’s history of reading. But the real colossus in this movement was the Durants who worked from 1935 to ’75 in producing that unparalleled achievement in popular scholarship which I hauled home from the post office on that rainy afternoon in 1978. I was thrilled in 1992 when the popular American biographer and historian, William Manchester, (probably most renowned today for his three volume chronicle of Winston Churchill, The Last Lion) led the way in the acknowledgements page of his A World Lit Only by Fire: The Medieval Mind and the Renaissance, with a tribute to the Durants. “Let me set down those works which have been the underpinning of this volume. First – for their scope and rich detail – are three volumes from Will Durant’s Story of Civilization: volume 4, The Age of Faith; volume 5, The Renaissance; and volume 6, The Reformation. The events of those twelve centuries, from the sack of Rome in A.D. 410 to the beheading of Anne Boleyn in 1536, emerge from Durant’s pages in splendid array.” Almost twenty years ago, Manchester’s generosity of spirit cut clear across the bitchy temper of the time. That very same year saw the publication of a typically snide study by University of North Carolina professor Joan Shelley Rubin, The Making of Middlebrow Culture, which oozes with the contempt of the academy for the uncredentialed; a contempt which has only become more claustrophobically obnoxious today. Get a load of this cheap shot of Ms. Rubin’s: “The inexorable tide of specialization, coupled with the academization of American intellectual life, further eroded the role Durant and his cohorts had managed to preserve in the 1920s and 1930s. For college graduates and non-graduates alike, the idea that an ‘outline’ could adequately cover a subject they had forgotten or missed seemed, one imagines, increasingly untenable; so too did the practice of investing authority in a figure disconnected from a university.” The pseudo intellectual snobbery is outrageous. What accounts for Rubin’s need to discredit the work of anyone who would display such bad taste as to conduct a literary career outside of a university? Vocational insecurity, perhaps? Or envy of an era when writers served an unprecedentedly large and generalized audience that was hungry for knowledge and intellectual improvement? As far as this reader is concerned, it is writers with connections to universities who ought to be legally compelled to affix bright red stickers on their books to give their readers fair warning: DEADLY PROSE, PRONOUNCED SELF-HATRED AND STILTED POLITICAL DEBRIS AHEAD. Did the mavens of middlebrow culture occasionally make mistakes, overlook certain periods, dismiss certain figures or otherwise engage in unconscious acts of cultural chauvinism? Almost certainly. But they did so in honest and industrious pursuit of a large and coherent world view, which is something no writer should ever be ashamed to attempt. Rubin and her revisionist ilk commit far shabbier crimes than the popularisers, and they commit those crimes deliberately, hoping to advance their own dismal agendas by slagging writers who amassed audiences which they can only dream of. Even at its shallowest, it seems to me that the middlebrow movement was a more encouraging and constructive reflection of the intellectual aspirations of the general public than anything we see around us today.

5 Comments

David Warren

7/9/2020 01:32:05 pm

Lord Goodden, an especially fulsome "Bravo!" for your defence of learned, "middlebrow" historians, this morning. While I am myself given to highbrow posturing & sneers, I try to direct this at other highbrow toffs, who, as you say, perform far more egregious crimes deliberately, having never read anything "at large." A great specialized scholar will invariably reveal a very broad general education. We are afflicted today with highly credentialled, smelly & tedious garbage collectors, who are flattered & paid for their expertise, when their work is actually worthless.

Reply

Max Lucchesi

10/9/2020 10:59:40 am

Herman - After rereading your Durant post, I'm still trying to understand highbrow, middlebrow and lowbrow. Let's see if I have understood it. In Opera for example would Mozart be highbrow, Verdi middlebrow and Gilbert & Sullivan be lowbrow. Or with crime writers; Raymond Chandler and Daphne Du Mauruer highbrow, Agathe Christie and P.D. James middlebrow, Sax Rohmer and Leslie Charteris lowbrow. I ask because to me historians have always been either honestly objective or partisan depending on whose history they are writing about. If I want to read American histor,y I will read a European author, likewise to read European history I will read an American. In my experience very very few historians are completely objective about the sins of their own country while happily describing the sins of others. Having never read Ariel and Will Durant can I assume that their worldview didn't fully research each volume but gave an honest (given prevailing attitudes) overview of each subject? Is middlebrow to you a less than fully researched but acceptable and populist view of the world?

Reply

Herman Goodden

10/9/2020 11:40:32 am

Dear Max - I don't know if I would be so absolute in discounting the validity of historians writing from within their own national culture (it's tricky but I think it can be done well), but otherwise your take on the different brow classifications sounds about right. Just as key in this matter as the writer's particular gifts and attitudes, is the audience who are drawn to take up his or her work. I realize this is a little lowbrow of me, but if you'll permit me to quote myself, I think I captured what I'm getting at here last winter in a piece about about J.B. Priestley:

Reply

Max Lucchesi

12/9/2020 01:37:22 am

Herman - I agree that some historians and cultural writers are objective about their own countries. They are very few and as you've pointed out, generally head and shoulders above their contemporaries. But myth and legend are embedded into a country's psyche and a lie told often enough becomes truth. As to 'popular culture'! During 2011 I was in Italy. It was the 150th anniversary of Italian reunification. That year Nabucco was being staged all over the country. I attended a performance on the quayside at San Benedetto. When the chorus began ' Va Pensiero' the 1000+ audience joined them, note and word perfect. Would that be popular culture?

Michael Menear

18/9/2020 11:16:39 am

H.L.Mencken in his Diary (entry May 14, 1945) wrote: I have written a letter to Will Durant, whose "Caesar and Christ" I have just finished reading, and another to his publisher, Max Shuster, congratulating them on the excellence of the book. It is a thing of really extraordinary merit - beautifully designed, full of sound learning and sound sense, and wholly free of platitude and sentimentality. There is probably no better conspectus of Roman history or of early Christian history in English. I let it lie on my table for months without looking into it, for my opinion of Durant was not too high. He seemed to me to be only a popularizer, and full of unwarranted pretensions. But now he has done a serious historical work of genuine value, and I have read it with great pleasure.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed