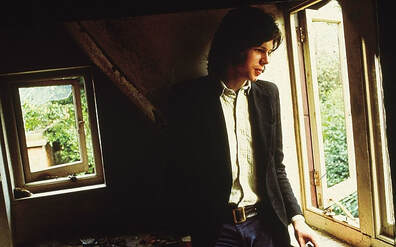

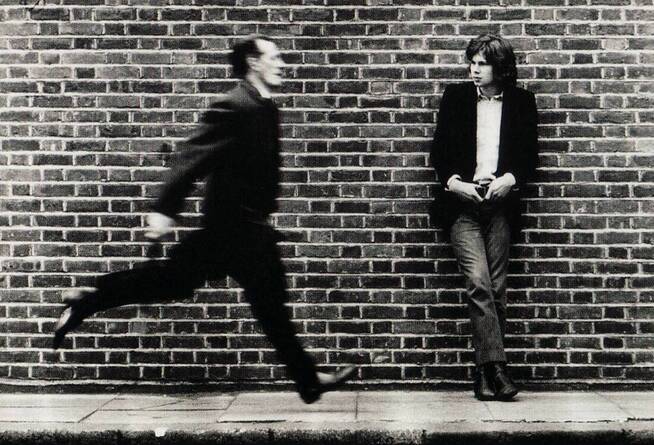

LONDON, ONTARIO – It was forty-five years ago last November that Nick Drake (1948-74), lying low at his parents’ comfy Warwickshire home and depressed out of his gourd because his life and his brain and his musical career were all spiraling out of control, killed himself by ingesting more than thirty Tryptizol anti-depressant tablets. He was twenty-six years old and left behind three arrestingly melancholy albums of utterly original songs – Five Leaves Left (1969), Bryter Layter (1971) and Pink Moon (1972) – that hadn’t sold worth spit or garnered much in the way of critical attention during his lifetime. And then, of course, as is the maddening way with such things, death was the charm - or better yet, the key – that gradually at first and then more and more completely, finally forced some movement within the seized-up padlock that had so cruelly kept him tethered to the earth. Premature death drew attention in a way that his beguilingly mysterious songs never had. And as the legend of Nick Drake started to lift away and attain ever loftier heights of adulation, the tortured musician increasingly came to be seen as this tragic Byronic figure whose heart and whose gifts were too perfect for this world. While that overstatement is almost as grotesque as the indifference which so discouraged him, the cultic devotion which attends him today does at least bestow one gift which would have brought him great satisfaction. He has not been forgotten and nearly half a century after his death, millions of people still have his music to conjure with. There is a kind of forecast of his transformed reputation in the line of lyric from the last song of the last album released in his lifetime which his family engraved on his simple tombstone: “And now we rise and we are everywhere.” If Nick Drake could somehow be resurrected for a day, what would this profoundly shy and artistically driven soul make of the vastly increased audience he has amassed for his body of work? Would he feel vindicated by the esteem in which he is held by his one-time colleagues and fellow musicians? What would he make of all the books, the biographies and critical studies of his music, which have appeared over the last twenty years? FIVE YEARS AGO the singer-songwriter’s sister, the actress Gabrielle Drake (most famous at our house for playing Inspector Lynley’s mum, Lady Asherton) lovingly assembled and published a nearly 500-page monument to his life and career and influence, Nick Drake: Remembered for a While. Emily M. Keeler wrote about that book the week it was published in The National Post, empathizing with the impulse to commemorate but declaring the book disproportionate; calling it, “an exercise in exquisite futility: Despite what we may wish, there is simply not enough material to make Drake into the master we long for him to have been . . . the project in the end feels hollow; no matter how deeply Drake’s loved ones may grieve him, the man who made Pink Moon is gone, and he left so little behind that we’ll never get enough.” I wouldn’t be so hard on the book or the man. I can think of a lot of important musical acts whose catalogues are similarly truncated and yet they still managed to put enough across in so limited a time as to constitute a significant legacy – the original four-man Traffic, for instance; Arthur Lee’s original Love, the horrible old Sex Pistols and the good old Mutton Birds. Over the four years of his recording career, Nick Drake might have had a fighting chance at minor star status if he’d been willing to get out there and work the clubs but while he seemed happy enough to play gigs during his student years at Cambridge University and a peripatetic year in France when he wrote a good number of the songs featured on his first album, he eventually grew to loathe performing. It is generally ascertained that his bouts of depression really started to mess with his life in 1970, in the silent year between his first and second albums. Bummed out by the indifferent sales of Five Leaves Left – the title taken from the notice that was printed on the fifth last sheet in a packet of rolling papers (yes, he smoked a lot of joints) – Drake was prescribed medication which plugged up his wells of inspiration, lifting his mood by flattening him out and leaving him lethargic and absent-minded. Fed up with that particular side-effect, he’d go off his medication and have a glorious day or two of manic productiveness before tumbling into a pit of even greater depression than before. He wanted to compose. He wanted to make records. In comparison to the wonderful work he knew he was achieving on those two fronts, performing seemed a waste of time. Describing one of Drake’s few live appearances, good friend, fellow musician and Island record label-mate, John Martyn, said, “He was cripplingly nervous. It was rather embarrassing in fact to see him. I mean the music was fine but he just didn’t like being there at all. I got the impression it was costing him too much to go on the stage. It was like no amount of applause or anything else would ever have paid him back for the mental energy and effort he had to expend.” While Drake would often be put on a bill with a reasonably copacetic act like the above-mentioned Martyn or Fairport Convention or Fotheringay, one shudders to think of the toll it took on this sensitive soul to open for such maximally amplified dunderheads as Atomic Rooster, The Climax Chicago Blues Band or May Blitz. A beautifully accomplished guitarist who never used a pick, a lot of Drake’s songs came with his own idiosyncratic tunings that required extensive adjustments to his instrument between songs. Never adept at genial between-song patter, this left lots of empty aural space for impatient louts to shout out spirit-wilting requests and nerve-shredding demands like, “Let’s boogie,” and “For the love of God, play Dust My Broom, why doncha?” THE LAST CONCERT of his life in June of 1970, Drake opened for Ralph McTell (of Streets of London fame) and from all accounts was actually going down pretty well. But by then he was already battling with catatonic depression and intermittent flares of paranoia and three songs into his gig, he suddenly decided that he couldn’t bear doing this anymore and simply walked off stage without saying a word. He must have known after pulling such a sad stunt, that no promoter in the land was likely to give him another shot. I wonder if some part of him wasn’t horrified to watch himself commit such violence against his prospects? (It is reported that late in his life he cornered an old associate in town and pathetically pleaded, “Tell me how I was. I used to have a brain. I used to be somebody. What happened to me?”) But I suspect a larger part of him was simply relieved that this particular form of misery at least was now over. Drake longed for other singers to interpret his material and leave him free to compose. But the problem there was he hadn’t yet garnered enough notice to make that possible. And even if he’d attained a higher profile, I used to think that was a vain and desperate hope because I simply couldn’t imagine any but his own ghostly voice ever doing justice to an exquisite jewel of a song like Northern Sky from my favourite of his albums, Bryter Layter. But a recent viewing on Youtube of a ninety-minute BBC tribute concert from 2010, Way to Blue: The Songs of Nick Drake, with the participation of folks like Teddy Thompson, Robyn Hitchcock, Kate St. John and Danny Thompson changed my mind on that score. Other people can do wonderful things with the Nick Drake canon. About a third of the songs in that concert are definitely goosed up a little; put across with more drive and pizazz than he ever mustered. And in a surprising testament to the sturdiness of his songwriting craft, those songs are not diminished or unduly distorted thereby. I’m not sure that I prefer any of those versions but they are worthy interpretations and treatments that reveal innate suppleness and transferable strengths that I never suspected that Drake’s songs possessed. Drake’s record company, his producer and a handful of fellow musicians all stood by him through his four-year decline in a way that I fear could not happen today. His producer and manager was the American-born Joe Boyd who produced a number of the finest British folk-rock acts that emerged in the mid-60s –The Incredible String Band, Fairport Convention and its dozen offshoots including Sandy Denny and Richard and Linda Thompson (for their first decade Fairport never had the same lineup on two consecutive albums), Shirley and Dolly Collins, Fotheringay, John & Beverly Martyn and Nick Drake. Boyd had a real fondness for all of the acts he worked with but even though Drake was the worst-selling artist on his roster, he took a particular interest in him. After working up the leaner, stripped-down songs that had so distinguished Pink Moon – just Drake’s voice and guitar and very occasional piano – Drake’s limited and intermittent confidence went into free-fall. There were a few clumsy and sporadic attempts to lay down tracks for a sketchily perceived fourth album but Drake took himself out of the picture before anything was finished. There are some sensitive souls (such as the one I married) who can’t listen to any Nick Drake as the sadness of it seeps into their bones and unnerves them. I feel that way about those final orphaned tracks which have been released as bonus cuts on various compilations; particularly one called Black-Eyed Dog where his usually smooth guitar playing feels jarring and panicky and he sings in this awful higher register that makes him sound like a terrified kid.  When Boyd sold off his production company’s recordings prior to returning to the States in the mid ‘70s, he attached a codicil to the contract stipulating that no Drake album would ever be allowed to go out of print. The purchasers of the entire catalogue of Witchseason productions may have grumbled at first but a mere twenty-six years after he was laid in the earth, Drake finally hit the big time (and has stayed there ever since as one of the most admired songwriters of the period) when Volkswagen decided to feature Pink Moon in a 1999 commercial for their Cabrio. This sublime sixty-second ad shows two college-aged couples out for a drive in a white convertible on a gorgeous moon-drenched night. As they blissfully cruise along over a bridge and down a winding country road, we watch the silvery light play on top of the river and flutter across farmers’ fields, all the while Drake strumming away and singing in his spectral, near-whisper of a voice, “I saw it written and I saw it say, ‘Pink Moon is on its way’ . . .” The Cabrio briefly pulls up at a noisy roadhouse party but no one makes a move to get out. Instead, we see the couples silently exchange conspiratorial glances with one another, as if to say, “Who’d want to go into that zoo on a night as sweet as this?” Then the car slips out of the parking lot and heads up a shiny ribbon of road to the far horizon. Yes, if Nick Drake had been in that car, he would've been alone. But otherwise the ad is an uncannily effective distillation of this musician's appeal. The Pink Moon album which had sold a paltry 6,000 copies in America between 1972 and 1998, sold 74,000 copies in 1999 alone and came with an unlikely promotional sticker plastered onto the shrink-wrap which read: “As featured in a TV advertising campaign.” (I mean, when has that ever happened before or since?) The two earlier albums started selling copiously as well, then a ‘Best Of’ album was issued and two further collections culled from stray cuts pulled out of the vaults. Included on one of these compilations called Family Tree, were two original songs composed and recorded by Nick’s mother, Molly Drake, on their household’s reel-to-reel tape recorder. It’s definitely a woman’s voice and her instrument is the piano but that voice’s timbre and phrasing, her affinity for sophisticated chords and the melancholic tinge of her lyrics leave no doubt from whom Nick obtained most of his musical instincts. Then in 2017 the Northumbrian folk duo, The Unthanks (comprised of sisters, Rachel and Becky Unthank) worked with Gabrielle Drake in putting out a complete album of The Songs and Poems of Molly Drake. Among the more remarkable essays and documents that Gabrielle Drake assembled in her hefty tombstone of a book, is the diary that Nick’s father, Rodney Drake, kept for the last two and a half years of Nick’s life; a journal exclusively devoted to his observations and concerns as his only son fell apart before his eyes. Bewildered and scared, the poor man and his wife are put through the wringer as they try to affix a workable grip to this heartbreaking process of dissolution. When they invite Rodney’s sister Pam who is suffering from Alzheimer’s to stay with them for a period as well, things take a turn for the surreal: “SUNDAY 18 NOVEMBER 1973 We returned to find Nick sitting in the drawing room watching TV with Pam who seemed pleased that he had sat with her but unable to recall if any words had passed between them.” And then a few weeks later: “A strange meal with Nick gazing in utter gloom at the floor and Pam standing about not really knowing what to do next but seeming unable to relax and sit down. Would all make a good Chekhov play no doubt but not a very happy one in which to find oneself participating.” With fond testimony from family members, childhood and university friends, producers, engineers and fellow musicians who helped out on his recordings, Gabrielle’s book highlights a sort of paradox that I think its subject, on one of his better days, would have appreciated. It’s a funny thing to say about a figure so apparently doomed. But Nick Drake was a lucky man to be surrounded by such good people who loved him so much and took such care to help this musician who in so many ways was so scarcely here at all, to leave such an indelible impression.

2 Comments

Max Lucchesi

12/5/2020 01:19:02 pm

Wow Herman, memories, memories! By 1969 I was a married man, but my wife's younger sister and her friends, like we had done, still frequented the Witches Cauldron in Belsize Village, where during the early 60s in the Coffee Bar's cellar musicians like Martin Carthy and Ram John Holden, Long John Baldry (when he still played his 12 string and sang folk) even a baby Rod Stewart cut their milk teeth. It never reached the heights or fame of the Troubadour in Old Compton Road as a folk and blues venue but it had its moments. John Martyn and Nick Drake came onto the Hampstead scene later. Most of these young musicians knew and sat in with and encouraged each other. Unhappily the innocence of that era died too soon when the 70s ushered in downers like reds, ludes and smack which took over from grass and hash as the high of choice for the hard core drug users, or of necessity for the vulnerable sensitives to cope with life. A darkness set in which by the 80s had taken by suicide or overdose too many talented lives. Even Tim Hardin passing through Hampstead during the 70s took a habit back to LA with him.

Reply

Bruce Parker

14/6/2020 01:36:39 pm

I am a big fan of Nick Drake and own nearly everything he has recorded. I have viewed all the Youtube docs about him. My son and I recorded a version of "Things Behind The Sun" for my FB page. Thank you for the insightful look into his brief life.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed