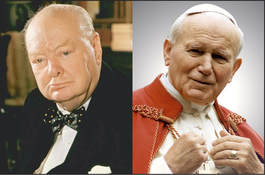

Winston Churchill & Pope John Paul II Winston Churchill & Pope John Paul II LONDON, ONTARIO – In my stash of Christmas books I received Lessons in Hope: My Unexpected Life with St. John Paul II, by Baltimore-born biographer and Catholic apologist, George Weigel, who reflects in a highly personal way on the 15 years he devoted to chronicling the life and times and impact of John Paul II in his two hefty and insight-packed volumes, Witness to Hope (1999) and The End and the Beginning (2010). Weigel’s account of both his own intellectual and spiritual formation and how he came to be invited by the Pope to take on the literary assignment of a lifetime is a tale that emphasizes, repeatedly and powerfully, the idea of providence. Early on in the book Weigel bestows on John Paul II, the first non-Italian Pope in 455 years, a designation I would not dispute, as “the emblematic figure of the second half of the 20th century.”

In terms of his service to the Church, John Paul II, who had done so much work as a Bishop and Archbishop of Krakow in developing dogmatic and pastoral constitutions for the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council, was perfectly situated to correct its often willful misinterpretation by proponents of such faddish movements as liberation and feminist theology. “The thought of John Paul II,” Weigel writes, “was not so much against the dominant liberal consensus of the post-Vatican II years as it was far beyond the progressive Catholic versus conservative Catholic civil war.” But Weigel’s characterization of this “emblematic figure” was not qualified or limited to just the Church but also signifies John Paul II’s impact on the world. And in terms of his service to the world, who but this Polish man of the cloth, trained to the priesthood in an underground seminary while the Nazi regime set its boot on the neck of the national church . . . and then when that horror had passed, patiently and courageously developed ingenious ways to shepherd his flock through 30 some years of Communist oppression . . . who was better equipped and situated to help the world finally – and non-violently – throw off the yoke of totalitarian tyranny? Karol Wojytla’s mother died when he was nine years old. His poor and motherless childhood was succeeded by the too-early deaths of his only brother and his father, leaving him completely without family by his 20th year. At the same time as he was forced to put in long days detonating charges in a limestone quarry, the pope-to-be risked execution by writing poetry and plays and acting for the underground Rhapsody Theatre with other young Polish intellectuals who were determined to keep the memory and traditions of Polish culture alive at a time when the Nazis were determined to eradicate all of it. In effect, Wojtyla spent all of his 58 years before ascending to the papacy learning how to secretly coexist and flourish, threading what sustaining life supports he could through hidden loopholes in oppressive political systems and then waiting, for decades if need be, until the perfect moment to push for substantive change. And all of those same principles were in play in John Paul II’s patient stage-managing of the Solidarity uprising which proved to be the critical linchpin in bringing down the tottering superstructure of international Communism. Weigel’s designation has set me to wondering who I would select as ‘the emblematic figure of the first half of the 20th century’ and I doubt I would be alone in choosing Winston Churchill for the way in which he rallied the conscience and determination of the world, first by discerning the magnitude and then standing all alone against the billowing tide of the Nazi threat. In comparing and contrasting the lives of Churchill and Karol Wojtyla, there are some definite parallels. Both men endured protracted periods of spiritual isolation during which they were persecuted and scorned for not going along with an officially imposed line that would have made their lives much easier at the cost of separating them from the truth. And when the ever-shifting constellations of fate were finally aligned just so and mankind faced some horrible new prospect, these two men in their respective times, were the only ones remotely equipped to handle the crisis. In such highly pitched battles of earth-shaping conflict, it’s hard not to feel the hand of God in setting these heroes in our midst. And in a way it seems to me that John Paul II saw through a final challenge that Churchill was prevented from fulfilling. At the Yalta Conference toward the end of World War II when the big three leaders of the Allied powers –Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin – met to chart the terms and the borders of the peace, Churchill was utterly thwarted. Yes, World War II was wrapping up but as Churchill wrote in a letter to his wife en route to that damp squib of a conference, “The misery of the whole world appalls me and I fear increasingly that new struggles may arise out of those we are successfully ending.” Roosevelt was visibly ailing and was so preoccupied with his own pet project of establishing the United Nations that Churchill no longer had his ear in the way he had before and couldn’t enlist him in a bid to try to persuade Stalin to dial back his dreams of consolidation. No nation had suffered greater loss of life in that war than the Soviet Union; even if half of the estimated total of 14 million Soviet deaths were executed in-house in various purges, pogroms, deliberate famines and as a result of forced labour. Churchill’s next ambition was to contain the massive post-war Soviet expansion which he knew was sure to follow but no one was prepared to stand with him to push against it. As he quite accurately lamented to his aide and confidant, Jock Colville, “All the Balkans, except Greece, are going to be Bolshevized; and there is nothing I can do to prevent it. There is nothing I can do for poor Poland.” Churchill’s eye for developing trouble was unerring. It was why you wanted him in charge in times of crisis and why an exhausted and bankrupt British electorate expressed their gratitude for his wartime leadership by turfing him out of office at the very first opportunity once open hostilities had ceased. No one had any further appetite for open armed struggle at that time and for the next four decades the Cold War quietly hummed away until – against all expectations - the Soviet Empire was peacefully dismantled by a religiously-infused movement of resistance which took much of its counsel and inspiration from John Paul II. When I came into the Church in 1984, John Paul II had occupied St. Peter’s throne for six years. I can’t say he was a large part of what attracted me but he certainly didn’t make me take pause as I suspect the more erratic and impulsive Francis might if I were tussling with such a decision today. There was an integrity and a quiet, forthright courage to the man that were manifest from the very first words he spoke when he was introduced as Pope to the assembled crowd below in St. Peter’s Square: “Be not afraid!” I devoured English-language papal biographies as soon as they appeared, including New York Times journalist (and Fidel Castro biographer) Tad Szulc’s John Paul II: The Biography (1995) and Wall Street Journal war correspondent Jonathan Kwitney’s Man of the Century (1997). I preferred Kwitney’s to Szalc’s but both books missed the mark for me with way too much emphasis on politics and an undiscerning and leaden grasp of theology. I started to wonder if only a Polish writer would be capable of taking a deep enough sounding of the man. But then along came George Weigel in 1999 with his first 1,000 page installment of the Pope’s life up to that point – and all was put triumphantly right. Some critics have taken the line that Weigel’s latest book is a bit of an ego trip with way too much about himself. But his subtitle, “My Unexpected Life With . . .” should have given fair warning that the real focus of this astonishing tale was to unravel the providential way in which a mild-mannered policy wonk in conservative American think tanks was invited by the Bishop of Rome to write his authorized biography. And the very first step, Weigel believes, was taken during Lent of 1960 when all the classes at his parochial school were instructed to pray for six weeks for the conversion of a different Communist dictator. He and his schoolmates had at least heard of the supreme Soviet dictator, Nikita Kruschev, but Weigel figures a bigwig like that was probably reserved for “the lordly souls of the eighth grade”. There was disappointment, he recalls, when Sister Florence wrote the name of the Kremlin’s big cheese in Poland on the blackboard in capital letters absent the Polish orthography – one Wladysla Gomulka. “I doubt that even my classmates of Polish extraction knew of this miscreant. And while I can’t remember how we pronounced his name during the next month and a half of prayer for his conversion, I’m sure we pronounced it incorrectly.” And yet Weigel is convinced that all those decades ago, a very strong hint regarding his own life’s mission was set before him that day: “Had anyone told me that, some thirty years later, I would write books in which Wladysla Gomulka’s complex role in postwar Polish history figured prominently, I would have thought the prognosticator mad. Yet there it is. And please don’t tell me those weeks of Lenten prayer in 1960 for Comrade Gomulka’s conversion – seemingly unanswered – didn’t have something to do with planting in me a seed that would finally flower in a passion for Polish history and literature – and a determination to tell the story of a then-forty-year-old auxiliary bishop of Krakow whom Gromulka and his associates foolishly thought a mystically inclined intellectual they could manipulate.”

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed