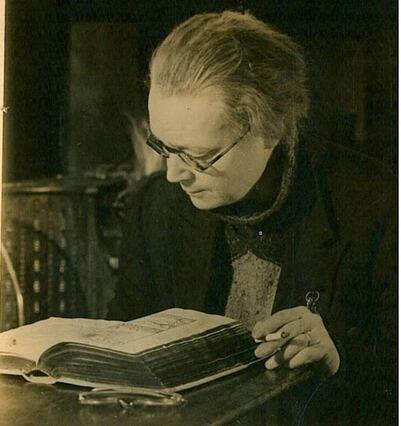

Dorothy L. Sayers 1893 – 1957 Dorothy L. Sayers 1893 – 1957 LONDON, ONTARIO – About a half year ago our son outfitted his digitally-challenged parents with a remote control device that we can speak into and magically instruct our oh-so ‘smart’ television to retrieve some program from the outer ether and pop it up onto our screen. In January and February when I was flying low with some physical afflictions that I described a couple of Hermaneutics ago, I was spending a few hours most nights on the couch revisiting forty and fifty year-old dramatizations of Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey mysteries. While this snappy new remote spares us the aggro of all that sausage-fingered poking at a finicky little keyboard, you do have to enunciate your request quite clearly or else that wheel indicating that the interwebs are being scanned to no avail starts spinning away on your screen, just above the message: “No results for ‘Dorothy Ulcers’.” I laughed when I saw it but there was something sadly familiar about that algorithmic failure to ‘get’ Dorothy L. Sayers (1893–1957). A large woman in every sense of the term, it seems there was just too much going on in this one remarkable life for most people to take it all in. She was a bold, knowledgeable and preternaturally prolific writer who scored major successes in four very distinct fields – murder mysteries; sacred drama; Christian apologetics; and. as both a translator and commentator, medieval scholarship. I have laid out those fields of endeavor in the order by which they became her primary focus. And while she never worked away in anything resembling obscurity, each switch in focus shifted her a little further away from a broad-based fame to smaller and more specialized audiences. While nearly all of her books are still in print – and 2023 will be the hundredth anniversary of the publication of the very first Wimsey mystery, Whose Body? – the print run for these different kinds of books has always varied wildly. There are probably twenty readers of Sayers’ mysteries for each person who has felt moved to take up her translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Easing herself out of the spotlight’s very brightest glow for the last third of her life, doubtless brought Sayers a measure of relief. Though few writers could match her bravery in speaking her mind – Unpopular Opinions, she defiantly entitled one of her essay collections – she was a temperamentally shy woman who wanted most of all, to just be left to get on with her creative work. While there was occasional overlap along the way (such as pulling together a final collection of Wimsey short stories while working on the first of her religious plays), her progression from one field to the next was definite and unmixed. She didn’t have the dexterity of a C.S. Lewis or G.K. Chesterton (both of whom she knew well) which enabled those writers to juggle several genres simultaneously. When she zeroed in on a new area of creativity, she went there completely. And that singularity of focus seemed to rub off on her readers as well. Many people who consider themselves Sayers’ enthusiasts, are crazy for her mysteries or perhaps her apologetics but rarely venture near her other kinds of work at all. It’s unusual to bump into anyone who can give an informed appraisal of her accomplishments in all four of those fields. Another factor discouraging broad comprehension was the public prickliness of Sayers herself. During her years of maximum celebrity, this author whose work had brought pleasure to so many, developed a harshly dismissive manner to keep time-wasting bores and nagging scrutiny at bay. And this sometimes proved difficult to switch off in situations where it was not necessary or helpful. At heart, Dorothy L. Sayers was a far more affable woman than her rather formidable and even glowering public persona could suggest. This author who was renowned for her insights into the dynamics of both human and divine love – and who was capable of a very high-spirited companionship with those she deemed her colleagues – had a real knack for keeping people at a distance. If the confidence and verve of her authorial voice drew people towards her, her public demeanor could push them away. This dichotomy frankly bewildered many readers who were perfectly prepared to like her until they met her. As a student at Oxford in the 1930s, the aspiring young writer, Penelope Fitzgerald, wondered what Sayers’ problem was when the celebrated author turned up at the Somerville College High Table, “austere, remote, almost cubical” in her outfit of “black crepe de Chine”, and pronounced to the dean “that the students dressed badly and had no sense of occasion.” It was the kind of disdainful slap in the face that could turn a young reader off the miserable old cow for life. In the years and decades following her death, a series of revelations came to light, showing why Sayers was so leery of even well-intentioned fans getting too close and digging around in her private life. A number of people who thought they knew her well, were shocked to discover that their childless friend had given birth to a son out of wedlock in 1924 and secretly arranged for his care with her maternal cousin, Ivy Shrimpton, who ran a small-scale foster care service for orphans. Sayers own parents never knew they had a grandchild. Sayers liked to believe that she wasn’t so susceptible to emotional tides as most women. While this may have been true once she got older, it wasn’t the case in her early relations with men; nor in her feelings for the baby that she couldn’t keep. When she learned that her mother would be visiting Ivy for a couple of days on family business and would unknowingly see her infant grandson for the only time in her life, Sayers couldn’t help pleading with Ivy to take special note and, “Tell me what Mother thinks of him!” It did require something like stoicism for Sayers to never tell her son that she was his mother. Early on she told him she was his cousin and later on, she formally became his adoptive mother. By about the time Anthony went away to boarding school, he’d figured out the truth about this benevolent guardian who never lived with him but was constantly overseeing and facilitating his progress. Intuitively sensing her uneasiness on the matter, Anthony never admitted to her that he knew. Some of Sayers’ friends had known a thing or two about the disappointing husband of her middle age; a significantly older army vet and semi-retired journalist named Mac Fleming who was almost never seen with her in public and predeceased her by some years. Perhaps they’d even sensed how challenging it might be for a chap of not very distinguished achievements to be entwined with a relentlessly brilliant powerhouse like Sayers. But those friends had no inkling that one of the main reasons Sayers married Mac in the first place was so she could officially ‘adopt’ her own son and bring him into their home. Mac initially agreed to this plan and after a little hemming and hawing, young Anthony was adopted and legally given the last name of ‘Fleming’. But Mac dragged his heels on bringing Anthony to live with them for so long – and then became increasingly embittered as he succumbed to a plethora of debilitating physical ailments – that Sayers decided to leave Anthony with Ivy for the sake of the boy’s own happiness and well-being. Even before Mac started to fall apart, it wasn’t a stellar marriage. But at least it had started with better intentions, and for a few years provided some semblance of companionability; which is more than can be said for the miserable and degrading history Sayers had endured with men in her twenties. In writing famous essays such as Are Women Human? Sayers was in some ways a precursor to feminism’s second wave, though she bristled at being called a ‘feminist’ and had serious qualms about contraceptives, let alone abortion. She was a notably sane and generous-hearted advocate for improving the lot of women but was able to present her case without descending into that petulant pit of blaming men for all of the problems inherent to the human condition. Sayers was probably held back from that too common prejudice by her deep and abiding Christian faith. Grounded in the knowledge that all are flawed and largely fashion the crosses that they must bear, Sayers understood that very few marriages or relationships falter because only one of the parties is an exasperating pill to live with. However rigorous Sayers could be in calling others to task – and we’ll be quoting some bracing examples of this shortly – she was no less critical of herself; once scrawling across a page of unpublished memoirs in self-lacerating disgust, “I have made a muck of all my emotional relationships and I hate being beaten, so pretend not to care.” That word ‘pretend’ puts the lie to her claim of emotional imperviousness. Whatever sort of judgement one might pass on this utterly original writer who found emotional expression such a minefield – and who did indeed stumble from time to time but took full responsibility for her failures while constantly striving to uphold the highest ideals of her art and her faith – none would be more absurd than a declaration that, “This was a woman who did not care.” So let’s try to attain a truer and more complete picture of our fascinatingly complex subject. And what better place to start than by taking another run at our new-fangled remote control – pronouncing our subject’s name with the utmost elocutionary exactitude – to see what turns up this time? Of (ahem) Dorothy L. Sayers’ eleven Lord Peter Wimsey novels, written between 1923 and ’37, a total of eight were adapted for British television. The first batch aired from 1972 to ’75 with Ian Carmichael playing the highborn sleuth in comprehensive three and four-hour adaptations of Clouds of Witness, The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club, Five Red Herrings, Murder Must Advertise and The Nine Tailors. This usually foppish and lightweight actor might have seemed an unlikely candidate for the role. But as it turned out, Carmichael – who revered the Sayers mysteries and personally oversaw the development of these five projects - gave a beautifully tuned portrayal of this mannered but amiable detective who, at first glance, can seem pretty foppish and lightweight himself but soon reveals his own kind of integrity and depth. Then in 1987 Edward Petherbridge took over as Wimsey – in age, stature and owlish demeanor, a more obvious fit - in similarly extensive adaptations of the first three (and strongest) of the later novels, Strong Poison, Have His Carcase and Gaudy Night, in which Wimsey is smitten by and assiduously woos and finally wins the proud and cantankerous mystery writer, Harriet Vane; played here by Harriet Walter. Charged with murder in the first of those stories - and discovering the body in the second and briefly being considered a suspect for that murder as well – part of Vane’s reason for resisting Wimsey’s overtures for so long is her reluctance to intimately align herself with someone to whom she would always be beholden for saving her from the gallows. I shan’t deny that all of these productions lack the pacing and sheen of more contemporary detective serials. But I’ll happily exchange that slickness for something that wouldn’t be tolerated if these programs were made today; their bounteous wealth of Sayers’ character-rich dialogue. I will also allow that some of the acting is a little hammy compared to the more naturalistic style that predominates today. And I’ll even admit that some of the adaptations work better than others and that your chances of enjoyment may well depend on reading the books first so that you’re able to appreciate the worthy job the producers have done in carrying over such richly nuanced stories from the page to the screen. If I could recommend a best shot from each batch for a Sayers newbie to check out, I would give the nod to Carmichael’s The Nine Tailors and Petherbridge’s Strong Poison. With the exception of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories and G.K. Chesterton’s tales of Father Brown, I was slow to develop a taste for mysteries. I was about fifty before I came to appreciate that during those times when my brain was already cooking away with overriding preoccupations, it made sense to pick up some light but not utterly despicable diversion – by Agatha Christie, say, or Simon Brett - that wouldn’t make big demands on my already-occupied ‘grey cells’. It’s not a good sign if fluff like that is all you ever read but nobody will begrudge an avid reader five or six ‘holidays from significance’ per year. And then I discovered that there were other practitioners in this field - ingenious plotters and beautiful stylists capable of real psychological insight like Josephine Tey and Dorothy L. Sayers – whose mysteries repaid closer attention with far richer narrative rewards. I enthusiastically second the high evaluation that the next generation’s queen of British crime writers, P.D. James, paid to the Wimsey mysteries, when she wrote that “Sayers showed that it was possible to work within the constraints of a popular form and yet produce novels which could stand comparison with the best of mainstream fiction . . . Her novels have their place not only in the canon of the detective story, but as an enduring part of English popular literature.” At her peak of productivity, Dorothy L. Sayers was producing a new Wimsey mystery each year and they sold in such fabulous quantities that she was the mainstay of - and the ideological exception to - most of the other quasi-Socialist writers published by the firm of Victor Gollancz Ltd. Sayers was clearly amused that the hobbyish escapades of her moneyed toff sustained such a politically earnest publisher who shunned any trace of marketing trickery by issuing all of his books in the same severe, plain-yellow jackets. ‘Lighten up, comrades; it’s just money,’ Sayers seemed to be saying in a magazine article about why she endowed her detective hero with such an unconscionable amount of moolah: “Lord Peter’s large income (the source of which by the way I have never investigated) . . . I deliberately gave him . . . After all it cost me nothing and at that time I was particularly hard up and it gave me pleasure to spend his fortune for him. When I was dissatisfied with my single unfurnished room, I took a luxurious flat for him in Piccadilly. When my cheap rug got a hole in it, I ordered him an Aubusson carpet. When I had no money to pay my bus fare I presented him with a Daimler double-six, upholstered in a style of sober magnificence, and when I felt dull I let him drive it. I can heartily recommend this inexpensive way of furnishing to all who are discontented with their incomes. It relieves the mind and does no harm to anybody.” Striving to avoid the conveyer-belt feel of so many other detective series, Sayers took real pains to mix up the milieus of her Wimsey mysteries. Five Red Herrings (1931) is set in a Scottish fishing resort full of backbiting artists, based on the community where she and Mac liked to holiday in those few golden years before drinking, failing health and moodiness got the better of him. Gaudy Night (1935) is set at a pioneering Oxford women’s college (winkingly called ‘Shrewsbury’) that is modelled on Somerville where Sayers earned her Master of Arts in Modern Languages in the days before English universities deemed it quite proper to go fully co-ed.  DLS as a student at Oxford DLS as a student at Oxford And the centre of action in Murder Must Advertise (1933) is a central London advertising agency called Pym’s, based on the firm of Benson’s, where Sayers held down her most remunerative day job for nine years until she was able to sustain herself in what she called “genteel sufficiency” on the avails of writing alone. Two of Benson’s more ingenious campaigns that she devised for Colman’s Mustard and Guinness beer are still referenced today by historians of that particular trade. And her old employers were so tickled by the secondhand attention she threw their way with Murder Must Advertise, that they invited her back for a playfully solemn ceremony in 1950 when they unveiled a plaque next to their spiral staircase like the one on which that tale’s murder takes place. Another of Sayers’ innovations which the narrowest mystery purists disdain to this day, was the introduction of romance as a central and (they would say) distracting theme into the quartet of Wimsey novels that feature Harriet Vane, most particularly Gaudy Night. The real climax of that longest of her novels was the final reciprocation of Lord Peter’s love for Harriet. And while there was an intriguing mystery for the pair of them to solve in the preceding pages, it wasn’t – Heaven forfend! – a proper murder but was a campaign of vandalistic mischief enacted against the scholars of Shrewsbury as payback for the career-ruining exposure of another professor who had falsified his research. Unfazed by the squawking that tale provoked among the humorless, Sayers went on to subtitle Busman’s Honeymoon – the final installment in the Wimsey/Vane merger – A Love Story with Detective Interruptions. That 1937 novel (adapted from her play of the same title) also happened to be the last mystery novel she ever completed. When Harriet Vane made her debut in 1930’s Strong Poison – the precise halfway point of Sayers’ fourteen-year run as one of the most popular mystery novelists in the world – it was widely observed that this new character bore a more than passing resemblance to the author. This is, of course, a common enough trick of the trade. Nearly every writer, to some extent, pillages aspects and events from their own life to use in their fiction. And with Vanes’ Sayers-like advocacy for full equality and a healthy independence between the sexes . . . not to mention her vocation as a writer of popular mysteries . . . the link between author and character was a natural one for readers to make. What wasn’t fully appreciated until The Letters of Dorothy L. Sayers were issued in five volumes between 1995 and 2002, was the shocking extent to which the victim in Strong Poison – the man whose murder Harriet Vane almost swings for – was based upon the arrogant poet who consented to live with Sayers but did not reciprocate her love and would not marry her, let alone have children with her. During her first trial for the murder, Harriet Vane is perplexingly passive in asserting her innocence because, even if she didn’t put down the cad (who went on to marry another woman who already had a passel of children from two previous marriages), she would’ve liked to. Almost verbatim, all of these humiliating particulars were carried over from Sayers’ life to the pages of Strong Poison. The only part of that wretched and demoralizing affair she withheld was its life-altering coda; the out of wedlock baby which Sayers conceived on the rebound from the lout, recklessly throwing herself at another man who meant nothing to her at all. Although they didn’t know the half of it, readers were not mistaken in regarding Harriet Vane as something of a self-portrait. Then, watching how Peter Wimsey’s character was reshaped by his love for Miss Vane over the course of those four novels – outgrowing most of his silly assery, mellowing and maturing and developing new capacities for patience and empathy – some wags joked that Sayers was engaged in a particularly grandiose exercise of wish fulfillment: Not content with having created one of the most attractive heroes in popular literature, she then made him overhaul his wonderfully desirable self so that he might finally become worthy of his author’s own hand. Miss ‘Vain’ indeed. Well, that last jibe was funny but it wasn’t exactly fair. Dorothy L. Sayers was not some moony schoolgirl with a pen, dotting her ‘i’s with little hearts. And let’s not forget that Harriet Vane also had some irksome qualities that needed to be purged or refined before she was fit to wed Lord Peter; most of them having to do with an inculcated inability to trust. Considering what she’d been through, how easy it would have been for a more cynical or less stubborn writer than Sayers to retire Harriet Vane after Strong Poison; quietly discarding the possibility of self-giving love as a hopeless cause and going off in search of other themes with which to complicate Lord Peter’s life. Sayers’ creation of the Wimsey/Vane novels was, in its way, a courageous act of repentance and revaluation; requiring her to sift through the unworkable chaos of her private life and try to discern why things had played out so badly and how they might have gone differently. In this expansive act of literary imagination, Sayers was able to convey the kind of love that she had never experienced but still recognized and lauded as one of the primary keys for securing a fulfilled life. From Strong Poison to Busman’s Honeymoon, she mapped out the kind of understanding, devotion and trust that need to be in place for any marriage to become a boon for both of its participants and a fit nest for the children they create. Generations of readers have been drawn to these novels for their overarching love story which is every bit as compelling as the mysteries which the lovers investigate while simultaneously working out their mingled destiny. I thought it was a real testimony to what Sayers achieved in these books when a father I know approvingly referenced the union of Harriet and Lord Peter in his speech at his bookworm/daughter’s wedding. Among those who particularly esteemed the quartet of Vane/Wimsey mysteries, was British author Jill Paton Walsh (1937–2020) who was herself inspired to study at Oxford after reading Gaudy Night as a teenager. Originally a writer of children’s books who then turned to mysteries and adult fiction (her Knowledge of Angels was shortlisted for 1994’s Booker Prize), Paton Walsh was approached by the Sayers estate in the mid ‘90s to see if she would be interested in fleshing out Sayers’ fairly extensive notes for a fifth Wimsey/Vane novel, Thrones, Dominations. This appeared in 1998 and was rapturously well received. “It’s impossible to tell where Dorothy L. Sayers ends and Jill Paton Walsh begins,” marveled Ruth Rendell in the Sunday Times. Paton Walsh then expounded upon a light essay in which Sayers speculated on how the Wimseys might have coped during wartime, to produce A Presumption of Death in 2003. In 2010 came my favourite of the lot, The Attenbury Emeralds - based on nothing more than a single passing reference to an early case of Lord Peter’s. In this book even the Wimseys start to feel the pinch of post-World War II austerities. In 2013 Paton Walsh came up with The Late Scholar entirely on her own, with our favourite couple investigating the murder of several Fellows at an Oxford college circa 1950. While this last pastiche showed definite signs of authorial strain, I’m still willing to go another round if the report turns out to be true that a fifth and final Sayers/Paton Walsh concoction is set to be published later this year. As the success of Paton Walsh’s series shows, the popular appetite for Dorothy Sayers’ mysteries remains remarkably strong sixty-five years after her death. But by the mid-1930s, Sayers herself was beginning to feel boxed in by the requirements of the mystery genre and harbored ambitions to set Peter Wimsey aside and turn her hand to a ‘straight’ novel. To that end she started mining her earliest memories of life to see what gripping patterns and ideas emerged that might be worth developing. A not even thirty-page first-person memoir (An Edwardian Childhood, published in 2002 as a supplement to her Letters) recounted her infancy and young girlhood. She only took that first sketch as far as her fifth year. That was when her family moved from the gracious civility of Oxford to the comparative wilds of the Fen country where her clergyman father had accepted a curacy at a country church on the outskirts of the small town of Bluntisham. Sayers had long regarded that move as a kind of exile; removing her from casual contact with people her own age at just that point when a child ordinarily starts to explore the outer world and makes their first friends. Her sense of social isolation was heightened by her status as the only child of over-indulgent parents who hadn’t married until they were almost forty. A sibling or two might have cured Sayers’ tendency to self-absorption and helped her develop some interpersonal skills which, it must be admitted, were notably lacking in her earlier years. While living at Bluntisham her closest friend was her cousin, Ivy Shrimpton, who she didn’t get to see all that often and to whom she ruefully confessed several decades later, “I wish that I’d been given the rough with the smooth when I was a kid.” Except for that lack of contemporaries to round off some of her edges, it would be a mistake to regard Sayers’ childhood as in any way deprived. Her parents were very comfortably middle class and their family was outnumbered more than two times over by the hired help. They had a cook, a man servant, three maids and a governess as well as a man from Bluntisham who came out a couple times each week to take care of the property and grounds. Though the three-storey manse was a little run down when they first moved in, they spruced it up without bothering to install plumbing that extended any higher than the ground floor. The maids’ chores regularly entailed hauling water up and down the home’s multiple staircases. There were lots of spare rooms for putting up guests and as a child Dorothy even had separate nurseries for daytime and nighttime use. Revisiting her earliest childhood in this autobiographical essay, Sayers was suddenly sabotaged with a whole new appreciation for her Bluntisham home as well as the landscape, history and eerie atmosphere of East Anglia. In the urgent grip of this totally unexpected inspiration, she shoved her memoir and any plan to write a straight novel aside and began charting out what many people consider her very finest mystery. Taking in, for her, an unprecedentedly wide temporal, geographic and social vista, all of the action in The Nine Tailors (1934) comes to a head in the rural community surrounding a Fenland church much like the one where her father presided. And the character of that church’s lovably eccentric rector – the Reverend Theodore Venables – is modeled quite closely on him. While Peter Wimsey has an aesthetic appreciation for church architecture and music and art, he does not subscribe to any religion because he does not accept the existence of the soul. But this was the novel where Sayers came closest to forgetting her rule to keep her mysteries strictly secular. For all of the mayhem and villainy that any murder mystery must explore, one of the strongest impressions that The Nine Tailors conveys is the community-binding order and the rooted sense of purpose – in every sense of the word, the sanctuary – that a church can provide for its parishioners. In the book’s climax, as flood waters perilously rise and expand, villagers and farmers from miles around haul bedding and clothing up to the church on its natural elevation where they’ll be riding out the storm like passengers in Noah’s ark. And standing there in the church’s doorway, be-robed and be-stoled, is the fatherly Rector, “with the electoral roll-call of the parish in his hand . . . numbering his flock.” Sayers was taking such care with evoking the haunting atmosphere that permeates this book . . . writing powerful descriptions of the natural world that are without parallel in any of her other writing . . . boning up on details about cisterns, dykes and sluice gates as well as the art of bell-ringing and the carving of wooden angels in the rafters of the church . . . that she knew she wasn’t going to be able to meet her annual deadline for delivering another manuscript to Mr. Gollancz and do this novel the sort of justice it deserved. So she held The Nine Tailors back to finish up over the next year and pounded out the much zippier Murder Must Advertise in a little more than a month. And while that quicker and easier book is a lot of fun, it does include a couple of clunky bits – including a preposterous scene where Peter Wimsey dives from considerable height into the basin of a shallow fountain – that would almost certainly have been reworked if she’d been able to give more time to its composition. Two years later – after completing The Nine Tailors to her satisfaction - Sayers took up her abandoned memoir again and, recasting it as a considerably longer third-person narrative (also unpublished until 2002 in that same supplement to her Letters) she continued her life story up to the conclusion of her scholastic career at Oxford. Far and away, the predominant focus of this second memoir which she entitled Cat o’ Mary, is her intellectual formation. Though this second account is punctuated here and there with some invented sequences, they are not well integrated and are pretty easy to keep separate from the autobiography. And it’s interesting to note that Sayers was much more critical of her young self when writing in the third person. Sayers writes that she had “developed all the faults and peculiarities of an only child whose entire life is spent among grown-up people. She was self-absorbed, egotistical, timid, priggish and, in a mild sort of way, disobedient. With the exception of occasional fits of screaming temper, she was not a naughty child, and her disobedience was almost entirely of the passive kind. She disliked a direct order and obeyed it slowly and reluctantly, but her timidity, partly constitutional and partly acquired, held her closely within the confines of conventional behavior.” Until she headed off to a university prep school in her sixteenth year, Sayers was solely educated at home by her parents and a succession of governesses. She also received dance lessons and singing lessons and labored away on a child-sized violin whose screechings provoked Bob the canary to offer up a little counterpoint. Her mother taught her to read by the age of four, finding her daughter particularly responsive to anything that rhymed. It was also noted early on that the kid soaked up languages like a sponge. One of her governesses gave her a good grounding in French and another in German while her father taught her Latin. At thirteen she was reading (and adoring) The Three Musketeers in its original French and acting out ambitiously costumed scenes from Moliere for her parents’ entertainment. That same year, in a first stab at the literary form that she wouldn’t really take up until the second half of her career, she wrote her very first play entitled, Such is Fame, about a brilliant young author who gets into trouble for indiscreetly basing her characters on two of her aunts and spilling some family secrets in the process. From a very young age she was given the liberty of her father’s library and by the time she headed off to her prep school, she had read her way through most of Shakespeare, Milton and Pope, as well as Sir Walter Scott, Jane Austen, Charles Dickens and – an early hero who taught her much about writing mysteries and whose life she hoped to chronicle in a biography she never quite finished – Wilkie Collins. Dorothy L. Sayers was fifteen when she arrived as a boarder at the Godolphin School in Salisbury in January of 1909. She took to the regimen of a full-time student with such ardor that she never seems to have experienced a single moment of anything like homesickness. Indeed, the only time she uses the word ‘homesickness’ in her entire memoir is when she describes post-graduate life; working at her first ill-fitting jobs in publishing and teaching, and thinking back on her infinitely more ordered and productive days as a student. Out of the family vicarage for the very first time, you might expect her to drift away from, or at least start to question some aspects of the faith in which she’d been raised. But she stood firm and tried as best she could to continue making all of her observances as before. The only religious matter she found troubling was the alarming amount of sentimental gush that was on display in the services at Godolphin’s chapel, particularly while her class was being prepared for their confirmation ceremony which took place at Salisbury Cathedral. One of the central themes of the bracing Christian witness which Sayers produced in the latter half of her career is summarized in the title of what is probably her best known collection of religious essays, Creed or Chaos. In the opening paragraph of that book’s title essay she takes aim at just the sort of flabby religious emotionalism which she so deplored at Godolphin: “It is worse than useless for Christians to talk about the importance of Christian morality unless they are prepared to take their stand upon the fundamentals of Christian theology. It is a lie to say that dogma does not matter; it matters enormously. It is fatal to let people suppose that Christianity is only a mode of feeling; it is vitally necessary to insist that it is first and foremost a rational explanation of the universe. It is hopeless to offer Christianity as a vaguely idealistic aspiration of a simple and consoling kind; it is, on the contrary, a hard, tough, exacting, and complex doctrine steeped in a drastic and uncompromising realism. And it is fatal to imagine that everybody knows quite well what Christianity is and needs only a little encouragement to practice it. The brutal fact is that in this Christian country not one person in a hundred has the faintest notion what the church teaches about God or man or society or the person of Jesus Christ.” Sayers already possessed a verbal facility – spoken and written – that far outstripped her Godolphin classmates as well as an imperious sort of demeanor that wasn’t snobbish so much as socially clueless. In any of her classes that had to do with literature, history, languages or drama, she wasn’t above showboating to impress her teachers; a precocious ruse that backfired with some instructors and repelled many of her fellow students. Even as a teenager, Sayers had an utter inability to feign enthusiasm for anything that didn’t interest her and was prepared to stand apart from the herd quite comfortably. She was content to make just a few friends with girls who shared her drive to devote themselves to scholastic and artistic pursuits (whether they were part of the curriculum or not) and had a real gift for keeping such friends for life. The real bane of her life at Godolphin was athletics. Sayers never got over – and never wanted to get over – her hatred of sports and games and various routines that promoted physical fitness. This doubtless contributed to her inclination to obesity which became pronounced before she was out of her twenties and was never brought under any sort of control. That obesity came in kind of handy when it allowed her to conceal her pregnancy from her family and her colleagues at Benson’s until she headed out on a ‘vacation’ about a month before her due date and returned to her job - not much smaller – about a month after that with her son securely ensconced in the care of her cousin. In one of the later, unintegrated bits of Cat o’ Mary, Sayers’ bemused account of her heroine giving birth – “She was so unaccustomed to success in any physical undertaking” – perfectly catches her estranged bewilderment when, for once in her life, Sayers’ body decided to just go ahead and perform some enormously strenuous action whether its ostensible owner wanted it to or not. When combined with her chain smoking and the relentlessly chair-bound regimen of a writer who could sit at her desk for entire days on end, that obesity undoubtedly played its part in bringing on a fatal coronary thrombosis at the age of sixty-four. By the time she went up to Oxford in 1912, Sayers had reined in the worst of her propensity for showing off and was far more adept at getting along with a wider cross-section of her female peers. Unfortunately she wasn’t yet able to interact with young men so smoothly; clumsily repelling overtures from some men who didn’t appeal to her at all, and broadcasting her unrequited crushes on other fellows so recklessly that it became cause for embarrassment and awkwardness. However, being enrolled at a women’s college in an era when chaperones and curfews curtailed the opportunities for interaction between the sexes, Sayers’ troubles with men didn’t become so pronounced as they would be after she graduated.  DLS as President of the Detection Club DLS as President of the Detection Club Her letters home to her parents are remarkably open and candid – she even tells them about her crushes – and brim over with her enthusiasm for the scholarly life. Visiting lecturers included G.K. Chesterton whom she rather idolized for his Father Brown mysteries, his Christian apologetics and his critical essays. By the mid 1920’s she would come to know Chesterton very well as a fellow member and fellow president of a rowdy consortium of mystery writers called The Detection Club. And on the occasion of his death in 1936, she wrote a touching letter to his widow, Frances, saying, “I think, in some ways, G.K.’s books have become more a part of my mental make-up than those of any writer you could name.” At the other end of the spectrum was another visiting lecturer, George Bernard Shaw, whom she lavishly abominated, writing home to her parents, “Nobody could hate Bernard Shaw more than I do. But it isn’t ‘rot’ – it’s damnably clever half-truths. I’d like to wring the man’s neck!” About ten years later when she read and thoroughly approved of Shaw’s St. Joan, she instantly recognized what set that play apart from most of his dramatic contrivances. This time the plot came “ready-made” and the historical record had to be adhered to. “St. Joan is protected by history from his habitual last act perversities.” While two early biographies of Dorothy L. Sayers appeared in 1975 and 1981 by Janet Hitchman and James Brabazon, neither author had a sufficiently comprehensive grasp of her life or accomplishments to bring real coherence to the job. Brabazon’s from ’81 is the far better book, honorable in its intentions and loaded with insights and appreciations that are valuable as far as they go. Brabazon met Sayers as a young man when he acted in a production of one of her religious plays and had gone on to a long career in theatre and in the drama department of the BBC. His Dorothy L. Sayers had the blessing of – and considerable input from – Anthony Fleming, who was eager to see a better account of his mother’s life than Hitchman’s ill-tempered mess from six years before. Hitchman seemed to bear Sayers some kind of grudge and her off-puttingly prurient opus, entitled Such a Strange Lady, could have been accurately subtitled (with a nod to Busman’s Honeymoon) A Smear Job with Gynecological Interruptions. But the best account of her life by far emerged in 1993, when Dante biographer and Cambridge lecturer, Barbara Reynolds (1914–2015), produced Dorothy L. Sayers: Her Life and Soul. Reynolds first met Sayers in August of 1946 when the famous mystery novelist made a presentation on Dante to an international symposium being held at Cambridge by the Society for Italian Studies. Sayers was then known to have been beavering away on her own fresh translation of the Divine Comedy for the last three years and many classicists were dubious that the creator of Lord Peter Wimsey was up to the task. Not that it would have persuaded these dour gatekeepers that Sayers had any business intruding on their sacrosanct turf but her fascination with Dante was in fact of very long standing. In the very first words of the very first page of the very first Wimsey mystery, Whose Body?, Lord Peter makes his debut before his reading public by asking his cab driver to take him back home so he can fetch the catalogue he’ll need to make his bid at a rare book auction for a 1481 first Florence folio edition of Dante. More than forty years after Sayers took to that podium, Barbara Reynolds recalled the impact of her talk. “I took my seat that evening not expecting anything out of the ordinary. I was mistaken. Rereading that lecture now, I can see in it all the signs of a critical response which was to make Dante come alive for millions of readers of the Penguin Classics translation. At the time I knew only that I was listening to the most enjoyable lecture I had ever heard.” Reynolds became a close friend and an invaluable sounding board as Sayers pushed on for the final eleven years of her life in translating Dante’s masterpiece. When Sayers suddenly died in December of 1957, the third volume, Paradise was not yet finished and Reynolds was so intimately conversant with every aspect of the great project that she was the one appointed to complete the final thirteen cantos. In 1989, Reynolds wrote her first volume about her friend, The Passionate Intellect: Dorothy L. Sayers’ Encounter with Dante. And between 1995 and 2002 she was the editor of the five volume edition of The Letters of Dorothy L. Sayers, which I would put up there with Walter Hooper’s three-volume Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis and Sally Fitzgerald’s single volume, The Habit of Being: Letters of Flannery O’Connor, as the finest epistolary collections of the twentieth century. This is an estimation, by the way, which C.S. Lewis himself beat me to; writing to Sayers in late 1945 (and unnerving her just a little about how to adequately couch her next response to him): “Although you have so little time to write letters you are one of the great English letter writers.” He then added this little joke: “Awful vision for you – ‘It is often forgotten that Miss Sayers was known in her own day as an Author. We, who have been familiar from childhood with the Letters can hardly realize . . .’” In summarizing Sayers’ student career at Somerville College, Barbara Reynolds concludes, “Aesthetically, as well as emotionally, the Bach Choir seems to have been Dorothy’s most enriching experience at Oxford.” This choir rehearsed every Monday night in the University Museum of the Natural Sciences where they were put through their paces by a highly regarded and rather dashing conductor for whom Sayers developed one of her indiscreet crushes. Reynolds continues: “Her infatuation for Hugh Allan was demonstrated in an exaggerated manner and became something of a joke among her friends. Nevertheless, the experience of rehearsing under the baton of so expert and exacting a conductor, of taking part in the performance of works of such beauty and complexity gave a new dimension to her response to creativity and art. It was to remain with her all her life.” Sayers wrote a poem in 1915, To Members of the Bach Choir on Active Service, which duly appeared in The Oxford Magazine and was publicly commended to the choir by Maestro Allan (which must have thrilled her to the soles of her feet). A modern sensibility has to make a few allowances for its antique conventions. But it’s a beautifully accomplished poem which – playfully and solemnly – evokes her sense of purpose and fulfillment to be living a life devoted to study and the making of art at a great university. Now and again, o’ Monday nights, Do you see the little bicycle lights Twinkling by two, and three, and four? Do you see the open Museum door, And the fire-hose coiled on the dusty floor? Stuck waist-deep in a slimy trench, Your nostrils filled with the battle-stench, Reek of powder and smoke of shell, And poison fumes blowing straight from Hell – Do your senses ache for another smell? For the smell of fossils and sticks and stones, Camphor and mummies and old dry bones, Of strenuous singers, and gas and heat – While you strove for a tone that was pure and sweet In air you could cut with a baton’s beat? When the guns are dumb and the shouting still – Do you remember the pulses’ thrill When the loud voice leapt to a strong behest – O you that sang with so brave a zest: ‘Et iterum, venturus est’? * Maybe you’ve forgotten us, small your blame If we should forget you, foul our shame, Though on Monday nights, as in days bygone, Tenor with alto hurries on Past the bones of the iguanadon. From singer to singer the space is wide Where knee pressed knee once, side pressed side, And through every fugue that ripples and runs, And through every chorus that smites and stuns, There breaks the crash of your distant guns. Howbeit of this I am full fain, That the quick and the dead shall come again, And all together, I dare to guess, Sing Bach in Heaven – or Heaven were less Than this poor earth in mirthfulness. (* ‘And (when) he shall have come again’: The Latin phrase from the Nicene Creed which J.S. Bach included in the Credo of his B Minor Mass.) Working on the Oxford section of her second and longer autobiographical exercise – a task she undertook for the purpose of digging up a theme on which to build her straight novel and put her career on a different trajectory – Sayers was painfully reminded of the scholarly dreams of her young womanhood which she had been forced to set aside so that she could meet the exigent demands of supporting herself and her inconvenient child. By day she had become an ingenious writer of snappy advertising copy. And by night she had developed a series of stories and novels about a dashing detective which eventually made her famous throughout the English-speaking world. It wasn’t nothing. By a very long shot, it wasn’t nothing. But at that self-questioning juncture in her life, when she longed to harness her talents in service to the worthiest impulses of her will to create, everything she had accomplished so far seemed like a betrayal of her gifts. And then came the unexpected invitation that would set everything to rights. It was at just that uncertain moment, Sayers writes, that, “I was asked to go to Oxford and propose the toast of the University at a College Gaudy dinner. I had to ask myself exactly what it was for which one had to thank a university education, and came to the conclusion that it was, before everything, that habit of intellectual integrity which is at once the foundation and the result of scholarship.” On her forty-first birthday Sayers returned to deliver her toast to the college from which she’d graduated half a lifetime ago. Personally, creatively, it was for her a crystalizing moment. Barbara Reynolds summarizes Sayers’ epiphany thus: “The illumination she experienced at Oxford revealed to her clearly what it was she most valued: a love of learning for its own sake, the impersonal pursuit of truth and, in all things, intellectual integrity. She also discovered that assent to these ideals was in her case no mere cold abstraction. Passionate feeling accompanied conviction. A fusion of mind and heart occurred; what her intellect believed in she also loved. Her self was no longer divided.” Again she set aside her autobiographical project. It had served its purpose by giving her fresh inspiration; leading her to the animating ideal of absolute intellectual integrity which was to be her guiding light going forward in everything she wrote. And again, she took that inspiration and directly set to work – not on her long-considered straight novel – but on what would turn out to be her longest, least conventional and most introspective mystery of all, Gaudy Night. As it turned out, no straight novel ever would emerge from her pen. But there would be one more mystery – a comparatively modest capstone to the Wimsey/Vane saga - before Sayers switched her focus from fiction to the religiously informed dramas, essays and scholarly translations of her later life. Busman’s Honeymoon is nobody’s favourite Sayers. But it is a perfectly good mystery (better than some in her canon such as 1927’s Unnatural Death) and a fond and slightly indulgent farewell to Lord and Lady Wimsey as they begin their married life. It is not a culmination of what came before so much as a dress rehearsal for what lay ahead. Conceived and successfully produced as a play before it was adapted as her final novel, Busman’s Honeymoon taught Sayers a lot about stagecraft and pacing and how to employ dialogue as a narrative’s primary engine. It is often suggested that when Sayers switched her authorial focus, she looked back on all those mysteries with regret and even shame. She did not. Yes, she was ready to move on because she felt that she had accomplished what she could in that genre and was eager to flex different literary muscles. But those books had served a noble purpose in her life; providing her with a living when she needed one and a reputation for good work that would help to open new doors going forward. While she drew the line at proselytizing in what were, after all, supposed to be entertainments, what distinguishes so many of Sayers’ mysteries is how very many aspects she brought into them; the rich seams of knowledge and the array of meaty insights and themes that she was uniquely equipped to explore. The great goal in much of Sayers’ dramatic work was twofold. First of all she wanted to, as they say, ‘bring history alive’; to make it approachable and relevant and tangible to modern man. The fact that that phrase has become a cliché doesn’t mean that it’s often done well. And her second great goal was to scrape away the numbing encrustations of piety and convention so that she could drive home the fact that Jesus Christ was part of human history; that there were no airtight dividers separating the human from the divine: “that history was all of a piece and that the Bible was part of it.” In a delightfully subversive essay called, A Vote of Thanks to Cyrus, Sayers recalled how she first encountered Cyrus the Persian in a child-friendly rendering of Tales from Herodotus. And so she thought of him as “pigeon-holed in my mind with the Greeks and Romans” as a figure of human history. Then her perception of reality sustained “a shock as of sacrilege” when this historical personage “marched clean out of Herodotus and slap into the Bible” where reference to him suddenly turned up in the Old Testament story of Belshazzar’s Feast. So she then takes that memory of what we might call ‘context collision’ and pushes it along a little further; making us consider a very old story in a very fresh way by pretending that the late Apostle John’s reminiscences have just been gathered up in a long-anticipated book which is now being reviewed in the popular press: “Memoirs of Jesus Christ. By John Bar-Zebedee; edited by the Rev. John Elder, Vicar of St. Faith’s Ephesus (Kirk, 7s, 6d.) "The general public has had to wait a long time for these intimate personal impressions of a great preacher, though the substance of them has for many years been familiarly known in Church circles. The friends of Mr. Bar-Zebedee have frequently urged the octogenarian divine to commit his early memories to paper; this he has now done, with the assistance and under the careful editorship of the Vicar of St. Faith’s. The book fulfills a long-felt want. “Very little has actually been put in print about the striking personality who exercised so great an influence upon the last generation. The little anonymous collections of ‘Sayings’ by ‘Q’ is now, of course, out of print and unobtainable. This is less regrettable in that the greater part of it has been embodied in Mr. Marks’s brief obituary study and in the subsequent biographies of Mr. Matthews and Mr. Lucas (who, unhappily, was unable to complete his companion volume of the Acts of the Apostles). But hitherto, all these reports have been compiled at second hand. Now for the first time comes the testimony of a close friend of Jesus, and, as we should expect, it offers a wealth of fresh material . . .”  DLS while translating the Divine Comedy DLS while translating the Divine Comedy You can see the same revivifying principle at work in Sayers’ translation of the Divine Comedy, right from her insistence on entitling the first volume, Hell, instead of the customary and (by the 1940s) less provocative title, Inferno. And in her commentary to Hell, she fleshes out in very contemporary terms, just who these classifications of people are who are enduring the sumptuously described agonies of eternal damnation such as: The Falsifiers – “They may be taken to figure every kind of deceiver who tampers with the basic commodities by which society lives . . . the adulterators of food and drugs, jerry-builders, manufacturers of shoddy, and so forth – as well, of course, as the baseness of the individual self consenting to such dishonesty.” The Flatterers – “Dante did not live to see the full development of political propaganda, commercial advertisement, and sensational journalism, but he has prepared a place for them.” The Usurers – “may be taken as types of all economic and mechanical civilizations which multiply material luxuries at the expense of vital necessities and have no roots in the earth or in humanity.” And the Schismatics – “They are fanatics of party, seeing the world in a false perspective, and ready to rip up the whole fabric of society to gratify a sectional egoism.” Most of her religious plays - The Zeal of Thy House, The Devil to Pay, He that Should Come, The Just Vengeance, The Emperor Constantine - were commissioned by great cathedrals and drama festivals and saw limited productions before being issued as books that didn't exactly burn their way to the top of the bestseller charts. But her series of twelve linked half-hour radio scripts, commissioned by the BBC, had an enormous impact in its day and in book form, The Man Born to Be King continues to find many readers today. The series was first broadcast over Christmas and through to Easter in 1941/42 and repeated many times. I’ve long desired to hear these plays as well as read them and just this year the BBC is finally making available an ‘audiobook’ of their 1975 production of the series. Of course, an audiobook is another dumbfounding gizmo quite beyond my ken. But another one of my technologically astute children – bless her heart – promises me a set of dubbed CDs for my birthday (which is coming up sooner than she might think . . . nudge, nudge). From the moment Sayers received her first overture, inquiring if she would be interested in taking on the assignment, she was adamant that the work would be carried out on her terms: “If I did do it, I should make it a condition that I was allowed to introduce the character of Our Lord Himself, and to present the play with the same kind of realism that I used in the Nativity play, He That Should Come. I feel very strongly that the prohibition against representing Our Lord directly on the stage or in films (however necessary from certain points of view) tends to produce a sense of unreality which is very damaging to the ordinary man’s conception of Christianity. The device of indicating Christ’s presence by a ‘voice off’ or by a shaft of light, or a shadow, or what not, tends to suggest to people that He never was a real person at all, and this impression of unreality extends to all the other people in the drama, with the result that ‘Bible characters’ are felt to be quite different from ordinary human beings . . . Radio plays, therefore, seem to present an admirable medium through which to break down the convention of unreality surrounding Our Lord’s person and might well pave the way to a more vivid conception of the Divine Humanity which, at present, threatens to be lost in a kind of Appollinarian mist.” Yes, the BBC accepted those terms and things proceeded well with the development of the first scripts until Miss Jenkins, an obtuse consultant to the producer, suggested Miss Sayers might like to come in and meet with a committee to discuss some recommendations that she hoped Sayers would find helpful for fixing up some of the dialogue. The poor little idiot. Sayers fired back: “Oh, no, you don’t, my poppet! You won’t get me to do three days of exhausting travel to Bristol in order to argue about my plays with a committee. What goes into the play, and the language in which it is written is the author’s business. If the Management don’t like it, they reject the play, and there is an end of the contract.” Wounded feelings eventually repaired, everybody went back to work until a couple of months later when it was far more gingerly proposed that perhaps Sayers would care to consult with a certain Anglican bishop who had some concerns about the language she proposed to use in the big crucifixion scene Well, this time she resisted calling anybody a ‘poppet’ but continued to stand firm: “Look here, I rather think the time has come when I must dig my toes in a little . . . I cannot deal with the Bishop as I should deal with Miss Jenkins . . . but I am frankly appalled at the idea of getting through the Trial and Crucifixion scenes with all the ‘bad people’ having to be bottled down to expressions which could not possibly offend anybody. I will not allow the Roman soldiers to use barrack-room oaths, but they must behave like common soldiers hanging a common criminal, or where is the point of the story? Nobody cares . . . nowadays that Christ was ‘scourged, railed upon, buffeted, mocked and crucified’, because all those words have grown hypnotic with ecclesiastical use. But it does give people a slight shock to be shown that God was flogged, spat upon, called dirty names, slugged on the jaw, insulted with vulgar jokes, and spiked up on the gallows like an owl on a barn-door. That’s the thing the priests and people did – has the Bishop forgotten it?” There was some muttering about blasphemy and sensationalism when the first episodes were aired but such objections were soon washed away by the unprecedented popularity of this bold retelling of the life of Christ. Of the hundreds of letters of adulation which flooded into the BBC and were forwarded on to Sayers, none cheered her more than the note from a young boy who’d been evacuated during the Blitz and billeted with a family of devout Christians who made a point of tuning in the plays. He was so engrossed by these broadcasts and the fantastic story they told, that he supplemented them with readings from the Bible. “I know He didn’t stay dead,” he said at the bottom of his letter, “because I’ve been reading on ahead.” Another commendation that came Sayers’ way in the wake of the broadcasts was from the archbishop of Canterbury who wished to confer a Lambeth doctorate in divinity upon her; an honour which she declined. Barbara Reynolds explains: “Her reasons for doing so included her wish to remain independent as a secular writer. The label ‘Doctor of Divinity’ attached to her name would, she thought, lessen any influence she had as a commentator on social matters or as an expounder of the Christian faith. It might also, she feared, act as a constraint on the range and nature of her secular writing.” One speculates that another reason for turning down the honour was the usual one of not wanting to make herself too conspicuous, lest it inspire detractors to go rooting around in her private life for scandals that needed exposing. In her introduction to the print edition of The Man Born to be King, Sayers touches once again on the matter of ‘integrity’ which had become so central to her thinking. “It was assumed that my object in writing was ‘to do good’. But that was in fact not my object at all, though it was quite properly the object of those who commissioned the plays in the first place. My object was to tell that story to the best of my ability, within the medium at my disposal – in short, to make as good a work of art as I could. For a work of art that is not good and true in art is not true and good in any other respect.” This idea that a created work’s integrity of craftsmanship largely determines its trueness and goodness in the moral realm as well, aligns quite neatly with the thesis Sayers developed in my single favourite of all her books, The Mind of the Maker. Written at about the same time she was developing her scripts for The Man Born to be King, in this fascinating, one of a kind meditation on divine and human creativity, Sayers posits the Holy Trinity as the archetypal model for all artistic creation. The Father represents the originating idea or flash of inspiration. The Son is the incarnation of that idea into a form that can be sensibly perceived. And the Holy Ghost is the two-way flow of nourishing energy by which a created work communicates its meaning. “And these three are one,” Sayers writes, “each equally in itself the whole work, whereof none can exist without the other; and this is the image of the Trinity.” Sayers believed that a conscientious artist's best opportunity to redeem the inevitable mistakes of a lifetime, was to make a thing well; that "All the truth of the craftsman is in his craft." In one of her later letters to her now adult son who was going through a difficult patch owing to what he recognized as the impulsiveness and selfishness of his own temperament, Sayers counseled him to not regard ‘temperament’ as "an irreducible factor in any situation - something which cannot be modified, and to which, therefore, the universe ought to adapt itself.". By all means repair what you can, she told him. But don’t pretend that you’ll ever be able to perfect your flawed and perishable self. Ultimately, she consoled him, “What we make is more important than what we are, particularly if ‘making’ is our profession.”

5 Comments

Susan Cassan

28/4/2022 02:05:28 pm

What a splendid essay on one of my favorite authors. I want to find the posthumous books, since I avoided them for fear that they would spoil the perfection of the originals. I have never forgiven the travesty Kingsley Amis made of James Bond, and I was not willing to take a chance on finding out the same thing had happened to Sayers. Thank you for the comprehensive guide to her life and works, with new fields to explore, after thinking that it was all over. I think I can handle that audio book invention. Might be able to give you a little help with that….

Reply

Max Lucchesi

28/4/2022 02:06:38 pm

Wonderful piece Herman, you filled in many questions for me about one of my favourite sleuths. What kept you away so long, was it convalescence after your woes or irritation with me? You do Ian a slight disservice surely, he only acted the lightweight. He had a good war (as they say) commissioned in the 22nd. Dragoons, he saw service from the first day on Juno Beach 1944 to Northern Germany 1945 with the 22nd. gathering 10 battle honours along the way. Surely you remember 'I'm All Right Jack' 1956, Private's Progress 1959, School for Scoundrels 1960 and Heavens above 1963 films wherein he was surrounded by the best British comedy talent and never fluffed a line let or the side down. His portrayal of Whimsey and later Wooster were flawless.

Reply

Douglas Cassan

28/4/2022 02:07:55 pm

An amazing, informative and well-written column that deserves wider exposure (say The New Yorker or Antlantic Monthly). Your comment "the rich seams of knowledge and the array of meaty insights and themes that she was uniquely equipped to explore" applies equally here.

Reply

Mark Richardson

28/4/2022 02:09:02 pm

Thanks for this impressive assessment of Dorothy L. Sayers. She was worth the attention you gave her and, although I am only half way through your piece already I have designated it "a keeper".

Reply

Jim Ross

1/5/2022 07:01:06 pm

Wonderful, Herman. Read aloud, this work reveals your ear for words, and your eye for the shape of each thought. Thank you for your attention to this subject.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed