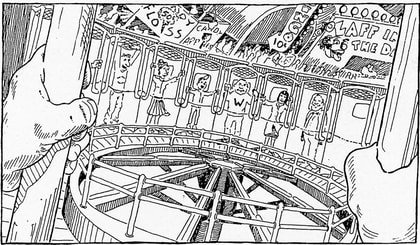

To commemorate the 144th edition of London, Ontario's Western Fair, here’s an old short story of mine (at least 50% fiction) inspired by a childhood visit to the Fair circa 1960. It was unusually cold that night at the Fair, more like Hallowe’en than early September, and I felt the excitement of any eight year-old who suddenly detects the approach of another season. This was new and this was familiar at the very same time; a sure sign that I was getting older and wiser, was finally getting the hang of the way things worked on Earth. Being a school night and a cold one to boot, the crowds were pretty thin on the midway. There were no serious lineups for any of the rides, and it was always easy to spot the slouching figure of my patiently bored father as he stood huddled in the doorway of fast food tents, obstructing the passage of paying customers and soaking up blasts of heat drenched in the smell of fried onions and grease. Without complaint or interest, he watched my progress as I blew his quarters on one ride after another – tossed and shaken by the illuminated arms of the Octopus and the Scrambler, unsettled by the careening floors of the Round-Up and the Tilt-a-Whirl, plunged into roller coaster valleys and lifted on high to tottering Ferris wheel heights.

The air grew even chillier as the sun went down but I was able to deny it all by absorbing the warmth of my own excitement and the imaginary warmth of the thousands of coloured lights that were coming on all over the midway. Stark shadows were projected from behind onto the bright canvas walls of sideshow tents; huge figures cast by the ordinary-sized people inside, expanding or shrinking at the will of the wind as gusts of breeze pressed the canvas taut or fell back and let it all go slack. The darker fell the night, the brighter glowed the tents and when they all were flapping and billowing together, I was reminded of the Chinese lanterns Dad always strung up at the cottage, suspended over the back yard on low-slung wire, bobbing and tossing with the breeze. My older brother, affecting a mature disdain for kid stuff which I knew damn well was a flimsy bit of camouflage to divert attention from his notoriously queasy stomach, had stuck to the barns and exhibition buildings all night long. He was twelve years old and probably bored stiff with tagging behind Mom and staring at prize-winning hens and heifers, blue ribbon pies and record-breaking pumpkins, but he was determined to avoid last year’s calamity – when I goaded him into joining me on the Salt & Pepper Shakers; a nasty little ride he’d found spectacularly upsetting. We’d been twirled and spun in two directions and motions when the ride had teasingly paused for a few seconds before kicking into an equally violent reverse. “Tell them to stop the ride,” moaned Richard in a voice as pale as his face. Thinking they were unlikely to do that, I tried to distract him by pointing out some of the sights below us, encouraging him to enjoy this wonderful view while he could. “Look,” I said, pointing to our right. “There’s the booth where we bought the corndogs.” Richard’s stomach went into a visible spasm like a cat that’s about to have kittens and, even though his restraining belt prevented him from assuming the preferred posture for vomiting, he erupted with a sputtering, grunting yodel that blew all kinds of unspeakable gunk clear across the cage where it hit the walls of metal mesh, some of it splashing back on him and soaking his shirt and pants, the rest of it luridly dripping and splattering onto the asphalt thirty feet below. I covered my mouth and nose and tried to breathe through my ears. Down below, people scattered for cover with screams and moans of disgust or else pointed at our cage and laughed. I could see Mom, emboldened by worry, break away from the crowd and exchange frantic words with the sneering hoodlum who operated our ride. Waving her away with a flustered motion, he leaned on a big gear shift that seemed to poke up out of the earth and slowly, gently, coaxed us back to terra firma. Dad gathered up his soiled and sickened first-born and led him away to the nearest restroom. Me and Mom waited for them to return on a nearby bench and watched the hoodlum hose out our cage and then send the ride up empty for a quick and efficient spin-dry. “See? They know what to do. It must happen all the time,” said Mom. And that’s why I was going on all the rides alone that year. Dad held up one splayed hand which indicated that I had only five more minutes until Richard and Mom would be rejoining us. I elected to conclude my solitary reveries on the tallest of the Ferris wheels, thus obtaining a summary overview of the lights and crowds of the Fair and half the town beyond; an aerial memory to see me through to next September. As I rounded the crest for the fifteenth time, I spotted Richard and Mom walking towards Dad and screamed out Richard’s name. Still touchy about his crummy stomach, Richard pretended not to hear me but Mom turned around and waved, a little blankly at first, until Dad stepped forward and pointed out where I was. When the ride concluded, I undid my own seat belt, ran down the wooden ramp leading to the midway and collided with a large fuzzy cushion that repelled me with a spring and sent me sprawling on my bum in the dirt and the dust of the fairground. The fuzzy cushion was actually a very tall soldier in uniform with an overflowing armload of stuffed animal prizes he’d won at Crown & Anchor and various games of skill. Cradled in his other arm was a young lady, just as soft and more voluptuous than any of his pandas; her eyes and mouth all sleepy and serene as she hugged him about the waist and burrowed her head on his chest. “You all right?” he asked as I scrambled to my feet, a little shaken and embarrassed. “Sure,” I told him, strictly casual, like nothing much had happened. “Give the little guy a bear,” his girlfriend urged, at which point I deduced that it might be to my advantage to play up this injury for whatever it was worth. I dusted my seat with elaborate concern and thought about improvising a limp to help dramatize my case. Fortunately, this wasn’t necessary as the soldier immediately picked up on his girlfriend’s suggestion. “Do you like any of these fellows?” he asked, indicating the stuffed menagerie in his right arm. I quickly surveyed the assorted beasts and narrowed down my choices, torn between a winsome chimpanzee with a rubber banana and a classic brown Roosevelt Teddy with minimal facial features. “Wait a minute,” said the soldier, suddenly remembering something and handing over his armful of animals to the lady in exchange for a carrier bag that had been hanging from her one free arm. “You’re getting too big for bears but I’ve got just the thing you need in here. Are you ready for this?” I nodded that I was and went a little mad with expectation. Being a soldier and all, he probably had a direct line on Lugers or bayonets. Maybe it was a Nazi helmet with a bullet hole blown through the front, jagged and rimmed with rusty red. Or a shrunken head that he’d picked up in some jungle and tied to his belt for a laugh. “No, Wally, not that. He’s just a kid,” said the lady, whetting my appetite absolutely for whatever was inside that bag. And then he pulled her out, alluringly, inch by inch, like some kind of mercantile striptease. First, a pink, pseudo-satin shade still wrapped in pleated protective plastic . . . a gold socket stem emerging from the crown of a dark-skinned lady’s head . . . a tropical flower tucked saucily behind one of her large-lobed ears . . . full red lips pushed out in a provocative pucker, just like Lena Horne’s on one of my Dad’s album covers . . . a long and slender neck . . . graceful shiny shoulders . . . great, naked, bulbous boobies, each with a little hard knob surrounded by a halo of deeper-toned flesh . . . an hourglass waist that grew ever narrower until it disappeared beneath the folds of a scanty robe . . . impossibly long legs bent at the knees and tucked underneath as she sat on a tasseled cushion. The lamp cord and plug poked out a small hole hidden in the back of the cushion. The forward thrust of her chest seemed to suggest the possibility of back pain and one of her hands may even have been placed behind so as to massage her spine but, to be perfectly honest, I really don’t remember anything about her hands or arms at all. I couldn’t take it all in right away and was actually going a little dizzy with everything she made me feel. Wasn’t this illegal? Wasn’t this fine? She made me feel something like hunger, something that wouldn’t quit, and yet just by gawking at her I felt like I was gorging myself in a most unseemly way. There’d probably be hell to pay when my parents saw her but she’d be worth the risk. I knew I wouldn’t be choosing any chimp with a rubber banana. “I’ll take the lamp,” I hotly declared, my voice cracking in its urgency. “I thought you might,” laughed the soldier and passed it over to me with a paternalistic pat to my shoulder. Then, looking askance at the approach of my parents, he quickly scooped up his girlfriend and the stuffed animals she’d been holding for him and they went off in the direction of the sideshows. “What have you got there? Let me see that thing,” said Mother in a tone of voice that warned me not to let this artifact leave my hands. Holding out the lamp with one hand firmly clutching her waist, I displayed some of the finer features to Mom. “Of all the nerve,” she said, staring after the soldier and his girl with a scalding disapproval that they must have felt all up and down their backsides even if they wouldn’t turn around to face it. “Will you just look at this,” she said to my father, hoping to elicit his disapproval as well; not having noticed that he’d been staring at it for some time and couldn’t bring himself to stop. I hadn’t owned the lamp for more than a minute but already I knew that this was one powerful piece of sculpture. When Richard started to laugh at Dad, Mother turned on him with a look of betrayal. She was so completely outnumbered that I started to feel sorry for her, was struck by how everyone seemed to take such delight in this lamp except the sole constituent of the gender whose form it purported to celebrate. I’d known her to disapprove of other things I’d wanted – like a dog and a chemistry set and a B.B. gun – until I’d shown that I was ready to take on some extra responsibility in order to have them, that there was a golden opportunity here for real learning and growth. So I tried that tack now, speaking in a matter-of-fact voice and expressing a mature interest in the workings of the human body. “So these are the tits – right? What are these called?” Mother exhaled deeply before correcting me. “The proper name is ‘breasts’. And nobody’s are as big as that.” “Breasts,” I repeated, as though committing to memory. “Okay, that’s what I’ll call them. And these?” “Nipples,” she said without enthusiasm. “Nipples. Do all ladies have them?” “Yes. And so do you.” “Not like that,” I couldn’t help roaring and started to smile when I heard Richard off to the side sputtering in congested mirth. “Ladies nipples have to be bigger,” she explained in an even, measured tone, “because ladies’ nipples have a use.” And then it hit me, like a bolt from the blue, and I actually dared to speak it. “They look like the tops on baby bottles. Do you mean you can use them like that?” “Exactly.” “You can drink out of them?” I asked in a tone infused with enthusiasm and wonder. “Babies can,” she said flatly, even sternly. “I get it.” “Do you?” she asked, her eyes searching so deeply into mine I started to get flustered. Why was she taking this all so seriously? What was really going on here, anyway? I’d had my two unclouded minutes of excited discovery and now the complications were piling up at a furious rate, encumbering my curiosity with defensiveness. Asking questions only seemed to make Mom angry, made Dad laugh and made me feel like a dope. Even Richard, who obviously understood volumes more than I on this subject, was a callow novice. I could sense it. He knew when to keep quiet and when to snicker at a fumbler but he obviously wasn’t holding any diplomas on the subject and when I tried to pump him for information later that night, he was infuriatingly coy, resorting to answers like, “You wouldn’t understand,” or “Mom’d kill me if I told you that.” So I was just as pleased when he trundled off to his own room and left me and my lamp alone. I’d set her up on my chest of drawers and plugged her in, leaving the usual overhead light switched off and bathing my room in a rich, undiluted pink glow. This sultry transformation was so pleasing that I couldn’t bring myself to turn it off at bedtime, couldn’t spoil the effect by turning on my harsh and sensible bedside lamp. The light was so poor and my mood so languid that I was unable to concentrate on my most recent issue of The Amazing Spiderman. “All that running around and beating people up,” I remember thinking as my lids grew heavy and I nestled deeper into the cushioned warmth of my bed. “Where does it ever get him?” And in my dream that night I was back at the Fair with the lady of the lamp and a strangely altered Spiderman. His outfit hung loosely from his muscled frame like really loud pyjamas and he didn’t seem to take things so seriously. Up and down the coloured midway he cavorted with my lady of the lamp, cracking jokes and roaring his laughter, pressing his thin and spidery lips against her moist and ample kisser, winning pandas and bears by the dozen, taking us for wonderful rides that seemed to melt into one another, never precisely beginning or ending, each ride amorphously capable of becoming like another. Spiderman kept annoying the lady by asking if she’d give us drinks. “No way,” she said, but sometimes when she was distracted, he’d reach out and grab one of her breasts, tilting it to his mouth like a dark, round wineskin pouring forth a luminous stream of warm and pearly milk until she’d catch on to what he was doing and abruptly pull away. “Come on, Spidey, that stuff’s for babies,” she’d say, going all cold and petulant and crossing her arms in front of her chest. Spiderman would sulk for a minute or two and then become charming and amusing again, waiting for her to forget and let down her guard so he could move in for another swig. About midnight I awoke as the folks were turning in. Perfectly still, I laid there watching through half-closed eyes as Mom stared doubtfully at the still-burning lamp. Setting her head at different angles, she examined it in closer detail than she’d been able to do before. After about a minute of this, she shook her head, reached out and turned it off but only started to move away. “Oh my God,” she whispered, still staring at the lamp and then went over to the door and called for my Dad. “Tom. Tom, come here and look at this,” she whispered. From clear across the darkened room, I could see the miracle she alluded to. The lady’s nipples, which always had seemed an unnaturally light colour compared to the rest of her flesh, had apparently been daubed with a phosphorescent paint and, in the darkness of my room, two green dots of ghostly light hovered in the air at the level of her chest. “Now that’s a set of headlamps,” my father said. Mother spun him around by the shoulders and aimed him towards the door. “Well, I think it’s sick,” she declared in a voice that wasn’t asking for his opinion or agreement. “That thing’s got to go.” The next morning at breakfast, no one was mentioning the lamp which left me feeling a little uneasy. It could mean they were reconciled to its existence and for this reason, I wasn’t going to start talking about it if they weren’t. But just as likely – or even more likely – it could mean their course of action was completely settled and they were just waiting for me to scoop up my lunch and head out the door so they could nip into my room and do her in. This would be a cowardly and conniving way for parents to behave but not to be ruled out in this instance. I wouldn’t know the fate of my lamp until I got home from school after a day of such anxiety and distraction that I’d be rendered scholastically useless. Out in the schoolyard, however, it was a red letter – indeed, a scarlet letter – day for education. From Richard in his infinite coyness the night before, I’d picked up on a number of strange loaded phrases like ‘facts of life,’ ‘birds and bees’ and a ‘house’ that belonged to somebody called ‘Hooer’. (This was what Richard said my room looked like after I switched on the lamp.) I set about getting these phrases explained. Our schoolyard harboured a sort of black market in dangerous information; a circle of older boys who flunked a lot and were always getting the strap, who wore unzipped bomber jackets all winter long and spent their recesses merrily spitting into one another’s faces or pelting passing automobiles with snowballs. It was simple enough to invade their circle and plunder their store of knowledge by assuming a subservient attitude and latching onto one of them in particular, charming the atmosphere with a few token expressions of admiration and praise. This shameless supplication was easy to assume at first but I gradually stiffened and started to crumble under the accumulating shock of what they told me. The real spoiler at the feast of sexual awakening was the sudden and totally unexpected implication of my parents – as irrefutable as my own existence – in such compellingly sordid behavior. If only I could have kept them out of it. I never expected that something so enticingly vulgar would ever appeal to them. And then to discover that they’d known all about it for years, had been at it for years, and that I was the one who was being kept in the dark . . . Dad, I believed, just might be capable of sinking so abysmally low. But Mother? Could this possibly be the same woman who wanted to drive all graven images of lust from our home? What kind of hypocrite was she? What kind of fool had they played me for? All this new information was about as coarsely expressed as humanly possible, and my main mentor, a gangly fifteen year-old named Deke with heavy tobacco breath and drooping watery eyes, actually did what he could to soften the impact of the news. Some of his friends were taking a loutish delight in slandering my mother, assaulting her character and honour in the same instant as I too was starting to doubt them. In my churning confusion of anger and bewilderment, Deke could see I was getting worked up to a fine pitch of madness and soon might fly into a desperate fight that I’d be certain to lose. “You got what you came for,” he said, pulling me away from his friends. “I think you’d better get out of here.” He gave me a push yet stayed with me for a few steps, moving just beyond the range of their hearing. “Don’t let them bug you. They don’t even know what they’re talking about. Hell – most of those guys still jerk off in their baseball mitts.” Though I didn’t quite get the joke, Deke couldn’t help smiling. “Cheer up, will ya? It can seem weird at first but it’s pretty neat stuff, ya know? Why shouldn’t moms be in on it too?” My only answer was to shrug my shoulders and blush a little more. “Give it a few weeks,” he said, turning to rejoin his friends. “You’ll come around.” Walking back toward the school, I saw the main floor window of our classroom, the patch of earth just outside it where earlier that week, one dog had mounted the back of another dog and vigorously wiggled its bum in and out – a sight that had reduced all the kids to laughter. “Mrs. Noseworthy, what are they doing?’ asked one of the boys in a strange enchanted voice that I now suspected may have been put on, and our teacher replied, “Well, I think that one dog is helping to scratch the other dog’s back.” And saying this, she pulled the curtains shut in a way that informed us that this particular line of inquiry was now closed. So, she knew what was going on too. Being Mrs. Noseworthy, she probably did it every night at home. It was going to be an awfully long time until I could look at my teacher again without unwillingly conjuring up gruesome vignettes from her bedroom. I heard a burst of moronic laughter behind me and turned to see a group of older boys who were engaged in a game where they’d make lunging grabs for one anothers testicles, jumping away and hooting whenever somebody missed, and moaning like bereaved cattle whenever somebody scored a clutch. Around and around they went, thrusting, yawping, recoiling and hooting, running themselves ragged in mindless animal delight. What would I have made of their game twenty-four hours ago? The cloud of my unknowing having finally been lifted, the magnitude and prevalence of this newest revealed truth was now apparent everywhere I looked. The world seemed suddenly drenched in sex and I was reeling like a Baptist hick set loose in the odium and the sin of Babylon. The lamp was gone. I hadn’t even said hello to Mother in my urgency to get to my bedroom and learn of its fate and now I stormed back down the hallway, through the living room and into the kitchen, calling for Mother as I’d call for a pesky dog who’d just absconded with one of my socks.” Where is it?” I demanded as Mom’s face emerged from behind a tall cupboard door. “Paul came down to pay his rent,” she said, referring to the new university student who’d just moved into our upstairs apartment for the year. “I was going to throw it out but he said he needed a reading lamp.” “So he can have it but I can’t?” “That’s right – he’s older.” “But it was given to me. It’s mine,” I said. And not wanting to hear her rebuttal to that fundamental fact, I turned and threw open the kitchen screen door and ran clattering up the fire escape stairs that led to Paul’s apartment. There, in the small unheated storeroom at the top of the stairs, I found the lamp resting on top of a stack of packing cases and boxes. Considering that my opinion of every other human being on Earth had taken a beating that day, I suppose I shouldn’t have been surprised to find that the lady of the lamp had also lost a great deal of her allure. I could see the cheapness, the vulgarity that had so offended my mother; detected a leering expression in her face that suddenly spoke of cruelty. If it weren’t for the principle of the thing, the fact that my mother had given away something that was rightfully mine, I was probably ready to give her away myself. This tramp of the lamp was hardly worth fighting for, yet this I readied myself to do. I grabbed her from the top of the crates in a spirit of tired bloody-mindedness, turned around and saw Mother at the bottom of the stairs, shaking her head from side to side. She didn’t have to say a word in order to set me off. “It’s mine,” I screamed, feverish as a baby throwing a tantrum, uselessly stamping my feet. Mother stayed where she was at the bottom of the stairs, fingers gripping each of the handrails, effectively blocking my escape. “I won’t have that thing in my house.” The steady firmness of her tone exhausted me. “Why not?” I shrilled in a strained and broken voice that was careening right out of control. “Just tell me why not?” “Because it’s disgusting.” “Well so are you!” I screamed and hoisted the lady overhead. “Don’t!” yelled Mother and I threw the lamp against a metal step halfway down the flight. Mother crouched behind splayed hands and it was then I realized I just might kill her, which really would be going too far. I screamed in rage as the lamp exploded on the stair, plaster shards and body parts flying in every direction as the pink shade wobbily bounced downstairs and halfway across the lawn. As the pieces settled, I stood there blubbering, eyes cast down on that shiny black stair now splattered with white plaster dust. I was paralyzed in an imaginary echo of the violence I’d committed, mostly relieved that the lamp was broken and gone, only wanting to find some way back to the world I’d known and trusted twenty-four hours ago. I could hear Mom’s voice growing steadily closer as she gently started her way upstairs. “Maybe I shouldn’t have given it to Paul,” she admitted. “I only meant it to be temporary until we could get him a decent lamp.” Now standing beside me, she produced a Kleenex from her apron pocket and held it to my nose for a blow; something I’d been too proud to let her do for two and a half years. “You’re ready to learn about certain things,” she said. “I can see that now. I could see it last night. And that’s why I was so concerned about the lamp. It made you ask so many questions. They were good questions and you need to have them answered but that lamp was a very bad beginning. And something tells me you already went out and got yourself some very bad answers.” I didn’t need to tell her I had, and together we sat at the top of the stairs, waiting for the echoes to die away and silently reconciling our spirits. This might have taken all of five minutes and then Mother stood up and took off her apron and started to fold it up. “I guess we’d better go into town and get Paul another lamp. Maybe two if you still want one.” I’d had about enough of lamps for a while but went along for the pleasure of being back in her company, inexpressibly relieved that for all the disagreement and disappointment that passed between us that day, no damage had been inflicted in either direction which foreclosed that sustaining possibility; confirming my temporary retreat from matters precociously pubic by acquiring the latest Spiderman annual during the walk back home. ILLUSTRATION: Roger Baker The Lady of the Lamp was first published in the 1988 short story collection, Counting Backwards from a Hundred.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed