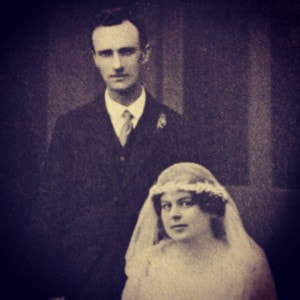

Frank and MaIsie on their wedding day Frank and MaIsie on their wedding day LONDON , ONTARIO – Striving to make good on my recent and reckless pledge to read every last unread book on my shelves before the Chinese Batflu lockdown is lifted and I’m allowed once again to freely pillage the second-hand shops, I’ve knocked back about fifteen titles in social isolation so far and only have a few hundred more to go. Yeh, I know. Restrictions are incrementally lifting as we speak and it’s starting to look like I might not pull it off. And even that slight inroad which I’ve made over these last nine word-drenched weeks is likely to be washed out this Friday when I observe my 68th birthday and the spirit of G.K. Chesterton will simultaneously blow out the 146 candles on his celestial cake. That is when my bookcases will be flooded with a fresh infusion of at least that many brand new (to me), gaily wrapped and ribbon-bedecked titles. But hey, not to despair. Maybe there’ll be a second wave of infections in the fall and we’ll go through this all again when I can hunker down with renewed vigour and give it another try.

Perhaps you’re wondering, “Just how does a person’s collection of books swell to such unmanageable proportions?” Well, it helps to be a completist; to seek to acquire every title by an author whether you’ve ever head of that particular book or not. Frank Sheed (1897–1982) and his wife, Maisie Ward (1889–1971) are two such authors for me. Frank’s literary forte was Catholic apologetics for thinking laymen. Among his more enduring titles are Theology and Sanity, To Know Christ Jesus and A Map of Life, and late in his life he also penned two wonderfully wise and religiously informed volumes of memoirs, The Church and I and The Instructed Heart: Soundings at Four Depths. (That latter memoir was primarily constructed around his recollections of and reflections on Maisie who predeceased him by eleven years.) Frank was also a dab hand at compiling anthologies on Catholic themes and worked up many translations of contemporary and classic works. I know a lot of people who prefer his translation of St. Augustine’s Confessions to all others. Maisie specialized in literary/religious biographies, producing lives of Robert Browning, John Henry Newman, and, most memorably, Gilbert Keith Chesterton. Published in 1943, Maisie’s sprawling and affectionate tome, clocking in at almost 700 pages, was the first (and remains the best) of the numerous studies which GKC has inspired. In 1952, Maisie cranked out an additional 300 pager, Return to Chesterton, comprised entirely of supplementary information which readers, famous and obscure, had sent along to her. Other than full length biographies Maisie also wrote some splendid collections of shorter sketches of the early Church Fathers (Early Church Portrait Gallery), English mystics and saints (The English Way) and she also wrote the single best book I know on the history and operation of the Rosary (The Splendour of the Rosary). In addition to authors or books on certain subjects, many of us more hopeless bibliophiles also watch out for a certain publisher’s imprint on the book’s spine which will make us consider an otherwise enigmatic title. Press insignias from The Folio Society, Nonesuch or Ignatius always compel me to at least read the book’s jacket or an introductory page. But there is another publishing house whose products (so long as they were printed before the 1960s) I’ll always snap up. And – even though it flies in the face of everything we know about what it takes to run a profitable, international business – that publishing house was operated by these same two writers. From their company’s inception in 1926 until the rot set in after Vatican II, Sheed & Ward (with offices in London and New York) published excellent, orthodox Catholic writing. Born in Sydney, Australia to a young Irish / Catholic mother and an abusive alcoholic father, Frank Sheed was determined to make his own way in life as soon as possible and became a full scholarship student of law at Sydney University at the age of sixteen. The only difficulty with pursuing that line of work was that everything Frank learned about the legal system offended his moral nature. “As soon as I realized that some lawyers were paid more than others,” he told his son, “I knew there was no justice. You get only the amount of justice you can afford; no more, no less." As a way of putting off any ultimate reckonings about so unsavory a vocation, Frank traveled to England on a sort of literary pilgrimage before undertaking his final year of training for the law. In England he linked up with the Catholic Evidence Guild for whom he passed out pamphlets and undertook some outdoor speaking gigs in venues like Hyde Park. And it was through the Guild that he met his wife to be, Maisie Ward. I have a copy of the fourth edition of the 360 page guidebook, Catholic Evidence Training Outlines which Frank and Maisie compiled and published under the family imprint. Here are some guidelines lifted from a chapter on ‘The Mental Outlook of a Catholic Street Corner Apologist’: “We are servants of the crowd and must therefore give our very best. This means individual preparation for each lecture. Speaking unprepared becomes very easy after a time but it is a temptation to be resisted fiercely. A poor speaker doing his best is quite literally much better than a brilliant speaker doing his second best. We must try to like the crowd – even those members of it who most obviously do not like us. We must not be resentful if they find us dull and uninteresting. We probably are. Nor must we feel a sense of grievance if they misbehave. They did not invite us to come and talk to them. “Sarcasm is always a grave offense. The speaker must never hurt a questioner’s feelings. Never sneer. Never raise a laugh at someone’s expense. If a joke is made at your expense, do not be annoyed. If it is a good joke, enjoy it . . . Above all never pretend to know what one does not know . . . Do not resent criticism. You are not expected to like it, but there is no progress without it. The work must have a background of prayer. The Guildsman should aim at spending as much time before the Blessed Sacrament as he spends on the outdoor platform.” Maisie was descended from English country gentry; a family of eccentric and grievously under-employed Catholic converts. Only informed of the ‘facts of life’ on the night before her wedding, Maisie’s honeymoon was miraculously trauma-free and she took to marriage like a duck to water. Endearingly, for the rest of her life, she couldn’t help chortling lustily whenever some officious dope made reference to ‘social intercourse’. Marital matters aside, Maisie’s lifelong complaint when confronted with situations requiring a more practical grounding in the ways of the world, was, “I’m at such a disadvantage when faced with reality.” Maisie’s grandfather, William George Ward, was an Anglican priest who took part in the Oxford Movement and went over to Rome with John Henry Newman, subsequently editing The Dublin Review, the leading English-language Ultramontane journal. Maisie’s father, Wilfrid, inherited the editorship of the Review until his own death in 1915 and as his secretary, Maisie noted that his usual workday was comprised of only four hours desultory labour at his desk. Over the course of his very leisurely life, her father also wrote some stiflingly dull (but thorough) biographies of his father and Cardinal Newman. With her father’s death Maisie was suddenly casting about for new work to undertake. Frank and Maisie’s son, Wilfrid Sheed (an excellent novelist and essayist in his own right) wrote in his delightful autobiography, Frank and Maisie: A Memoir with Parents, “By 1919 Maisie was really at loose ends. Her father had died in 1915, and nobody had given a thought to another career for her. Why should she be different? Even men in her class didn’t have to do much of anything . . . If the Catholic Evidence Guild was a good chance for Frank, it was a blooming miracle for Maisie. Otherwise she would have been like all those great violinists who died before the violin was invented. She was, it turned out, a great outdoor speaker.” The young couple were married in 1925 and with Frank’s energy and drive (Maisie’s mother once opined that, “Frank could be in two places at once if there was a night train”) and Maisie’s solid grounding and connections in Catholic publishing circles, the new publishing house of Sheed & Ward was up and running within months of their nuptials. Not many writers have the inclination, the time or the self-confidence to develop or promote other writers but with characteristic modesty and steadiness, Frank always maintained that, “I’d rather lead an orchestra than play the flute.” And what an orchestra it was. The Sheed & Ward stable of writers was an international ‘Who’s Who’ of leading Catholic literary lights. G.K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc and Ronald Knox were the big stars and the real money-spinners but further down the list were numerous treasures. Historian Christopher Dawson wrote like a dream and brought a whole new dimension to a dozen or so books which pivot on the salvific participation of Jesus Christ in human history. In Dawson’s hands, that which secular historians rendered as a depressingly pointless catalogue of conquest and slaughter became an epic and ongoing drama of redemption. Eric Gill was a British artist and stone-cutter whose writings and way of life, perhaps a little too self-consciously, invoked the lost era of the guilds when devotion to God and fellow man motivated professional associations of craftsmen and workers. Still, it was wonderful to hear from an artist who struggled to reconcile his passion and his faith. Etienne Gilson was the most renowned Thomistic scholar of the day and Alfred Noyes was one of the most popular poets ("The highwayman came riding, riding . . ."). All kinds of priests like the English Jesuit Vincent McNabb and the Irish / American Leo J. Trese gathered together popular collections of homilies and retreat talks and Wilfrid Sheed lamented his father’s weakness for printing any sort of fluffery by scribbling nuns. I have one of those nun’s books – A Right to Be Merry by Sister Mary Francis of the Poor Clares published in 1956 – and find it to be a thoughtful, engaging and uncommonly well-written account of American convent life. I have another Sheed & Ward title from ten years later in which a professor of moral theology rattles on about “the laws of legitimate authority” which may be “normative for the Christian but are not always applicable” and that judging “their binding force and relevance in one’s own situation is the burden and freedom of conscience.” Yuck. The desiccated blight of Vatican II is upon us as exuberant fidelity is replaced by tedious, cadging, theological hair-splitting. Frank had no enthusiasm for these later books and sold Sheed & Ward in the late ‘60s, relieved that “nothing embarrassing would come out over his imprint again as long as he lived.” His own last books were published by other houses such as Doubleday and Our Sunday Visitor. After Frank’s death the left-leaning National Catholic Reporter acquired the Sheed & Ward name and the old family imprint appeared on fresh volumes of unorthodox drivel which neither of its founders would have countenanced for a minute. That arrangement thankfully came to an end in 1998 and Sheed & Ward has now gone quiet as an ongoing publishing entity. More recently, Father Fessio’s wonderful Ignatius Press has taken on the reprinting rights for dozens of titles by Frank and Maisie and many of the other writers who contributed to the glory years of the one-of-a-kind house which this remarkable couple built.

1 Comment

Max Lucchesi

27/5/2020 09:18:41 am

"Until the rot set in after Vatican II"! Which you and conservative Catholics continue to misunderstand and disparage. Unlike you Herman I was at school when Cardinal Roncalli in 1958 was elected Pope, I remember why Vatican II was called. I remember the relief Catholics, those, not of the Authoritarian, Medieval, Anti-Semitic Fascist and Nazi collaborating wing of the church felt, I remember the widespread post war disgust at the Church's actions from 1922 till the 50s. In Italy Pius XI collaboration with Mussolini, Pius XII's 'Failure of Pastoral Care' to the Reich and it's Occupied countries. How the Church encouraged Catholics to enlist in the SS' crusade against Communism and their subordinate Militias to help round up Jews. The concentration camps in Slovakia and Croatia staffed by Ordained Catholics. The Vatican rat runs from 1945 into the fifties to help wanted war criminals escape justice via Italy and Spain to South America. Why the relief? Roncalli was a known anti fascist who had helped hundreds if not thousands of Jews escape the occupied countries. He initiated Vatican II but it was Roncalli's successor Cardinal Montini another anti Fascist Jew helping Prelate who agreed with opening the windows to shed light onto the dark corners the filth hid in. By this time the apologists were already spinning the church's war time record pointing to the heroics of Roncalli and the Jesuit fathers, priests and Nuns of all orders and other individual Catholics who, despite the church's disapproval and hostility are commemorated at Jad Jashem as 'Righteous Among Nations'

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed