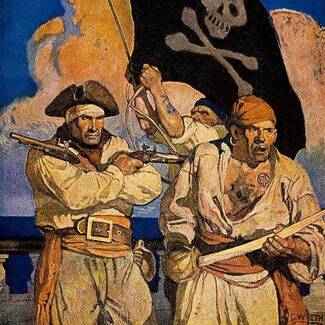

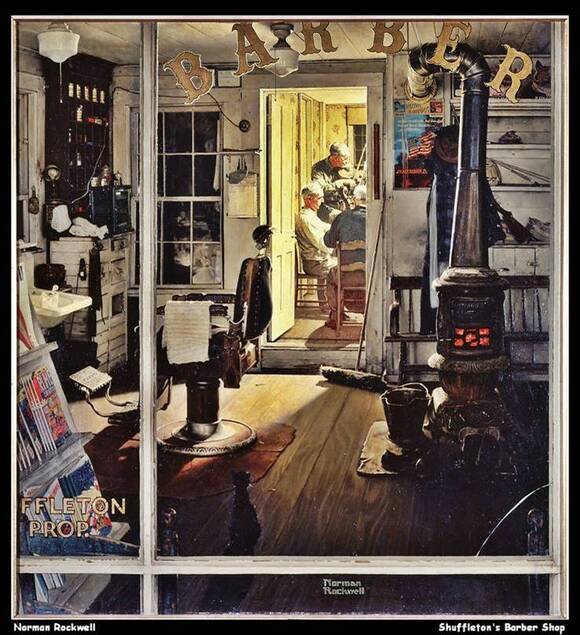

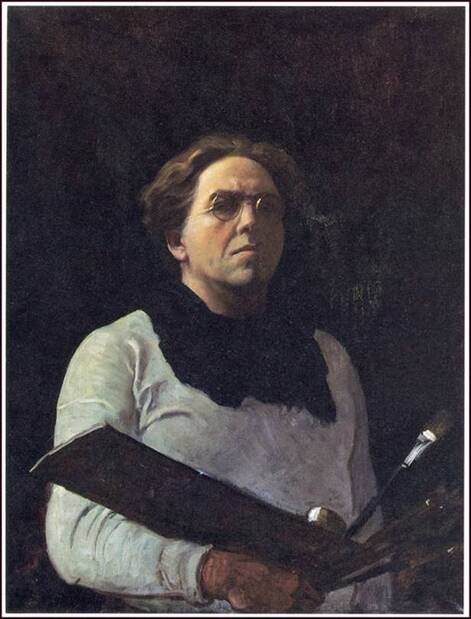

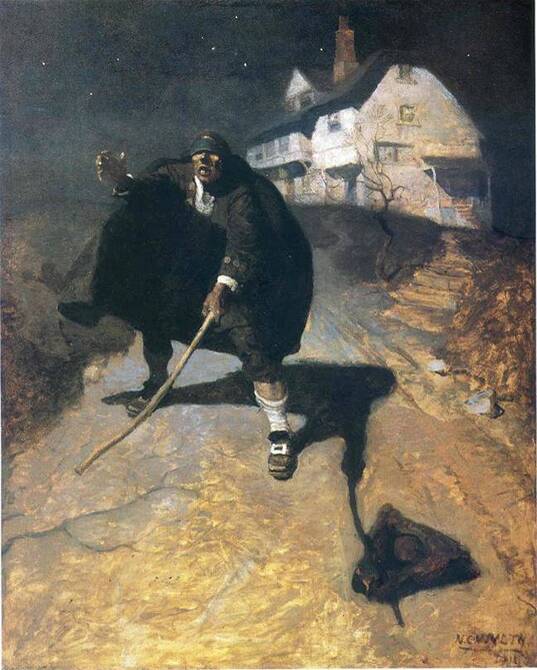

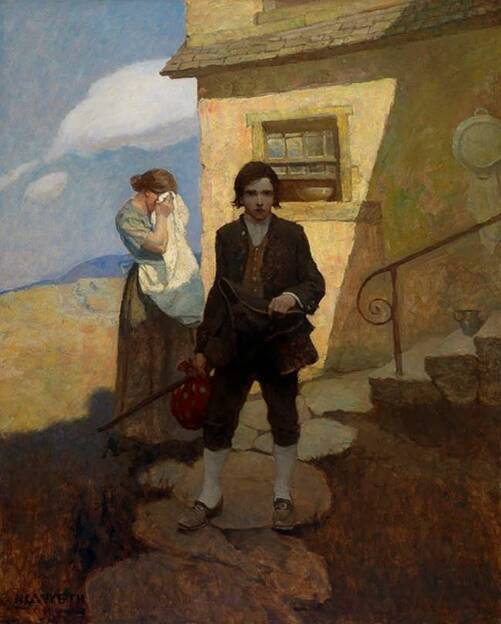

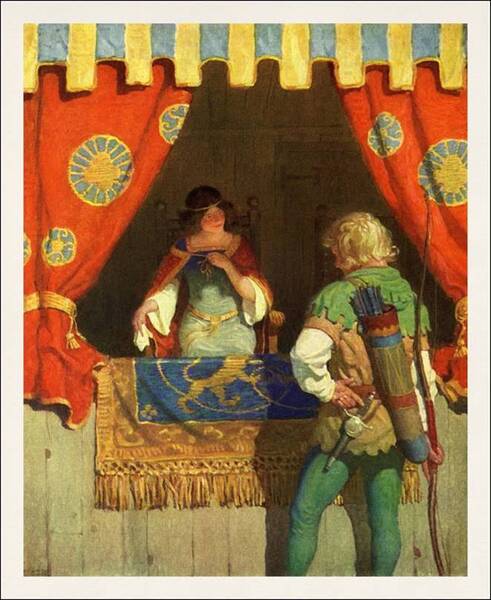

N.C. Wyeth: Treasure Island frontispiece N.C. Wyeth: Treasure Island frontispiece LONDON , ONTARIO - I was a little distracted this week with a couple of editing jobs, three shifts in a bookshop and that welcome uptick in socializing that is characteristic of summer’s end. So instead of some new concoction, Hermaneutics this week offers you an essay on George Orwell which I was delighted to land in Quillette late last month (https://quillette.com/2021/08/27/theres-a-lot-more-to-george-orwell-than-nineteen-eighty-four/) and this talk which I delivered to the Baconian Club of London in the spring of 2002. This speech, mostly focusing on the American artist, N.C. Wyeth, was my first extended meditation on visual art and taught me a thing or two about using my eyeballs and trusting my instincts when tackling an intimidating subject for which I retained no innate or specialized knowledge. Those lessons came in handy exactly ten years later when I took on the commission to write my book, Three Artists: Kurelek, Chambers and Curnoe (Elmwood Press, 2016). WHENEVER I'M TEMPTED to pity the lot of the workaday writer who must endure constant economic uncertainty and occasional week-long landslides of outraged letters to the editor denouncing positions he never promoted in the first place (at least not in that un-nuanced, mutton-headed way, thank you very much) I stop myself and think instead of the lot of poor workaday visual artists. Then a wonderful serenity suffuses my entire being and I sigh to myself in gratitude, “See? It could be so much worse.” At least most people know how to read printed words on a page and aren’t averse to picking up a newspaper or a book to learn about events, consider another perspective or just be entertained. It’s a far smaller pool of people who can ever be coaxed to set foot in an art gallery or have the foggiest notion how to appreciate any work of visual art. If I hadn’t grown up in a home with a budding artist brother and then gone on to marry an artist, I sometimes wonder if I would ever have developed an enthusiasm for the stuff on my own. Visual art might not yet be as esoteric a taste as opera or ballet, but it’s getting there. Tonight I am going to argue that this lack of widespread regard for or interest in the form, has enabled a perverse and dictatorial minority of taste-shapers to exclusively promote precisely the kind of work least likely to ever attract a popular audience, while suppressing and ignoring those works which might actually be able to turn that indifference around. Part of the problem has to do with our educational system. Visual art is the most poorly served category of all the arts in our schools. Unless you specialize in art or have the good fortune to attend an arts-enriched primary or secondary school like Lester B. Pearson or H.B. Beal, you’ll never be given an adequate grounding in the language and history of art. For the most part our society’s other great teacher, the mass media, don’t do much better. Only two kinds of art stories routinely make the news. One is the sale at auction of some recently discovered canvas – usually a Van Gogh – at a record-breaking price that elicits a strictly mercenary appreciation, like the avaricious groan evoked by that rather homely antediluvian door knocker on the Antiques Road Show that (“Well, I’ll be jiggered”) turns out to be worth a cool half million smackers. The price is the story, not the painting, though there’s usually a depressingly snide comment thrown in about how dear old Vincent, that poor one-eared maniac, never made a dime from his work in his entire, wretched life and wouldn’t it drive him even crazier if he could see the prices he’s fetching today? The other kind of story that’s given media play – and we’ve had two beauts this winter from Canada and Britain – concerns those grotesque or banal (and always aesthetically bereft) art works which rely entirely on novelty, shock, or hoax to elicit an incredulous response. In December the president of the Banff Centre (renowned as Canada’s leading professional development centre for the arts), was compelled to publicly apologize for sponsoring the seven week residency of Israel Mora, a Mexican conceptual artist who masturbated into glass vials which he then displayed on the shelves of a special little cart which he wheeled around Banff for the edification of all. Some of us have been referring to particularly lousy conceptual artists as ‘wankers’ for decades now, but strictly as a term of fanciful derision. We never hoped to see such perfectly vulgar and perfectly literal confirmation of our insult. Senor Mora’s visit to the great white north, sharing enlightenment and fresh spermatozoal fluids with his Canadian fans, netted him $4,000. By the time the details of his residency started to make the news, Senor Mora was scooting back to Mexico with his overworked member in his mitt, while the Banff Centre president got to work covering her own ass. As the Centre is 22% funded by the hapless Canadian taxpayer, the prez thought she’d better say something conciliatory before the funding tap got turned off completely, or was reduced to erratic ejaculatory spurts. In Britain the arts mavens are convinced that freakishness is the only quality that will dependably wrest the world’s attention. Wanting to top recent prize-winning sensations such as Tracy Emin’s unmade bed, Damien Hurst’s sliced and pickled animal carcasses, and that other bozo’s elephant dung painting of the Virgin Mary, the jury awarded this years $45,000 Turner Prize to Martin Creed for outfitting a bare room in the Tate Britain gallery with a commercially procured timer that makes the lights turn on and off every five seconds. The title for this masterwork? "Work 227: The lights going on and off." The Turner Prize has been annually awarded since 1984 (with the exception of 1990 when a sponsor willing to throw money at this crap couldn’t be found in time) for – and I quote - “a British artist under 50 for an outstanding exhibition or other presentation.” Two earlier works from Creed’s oeuvre that managed to generate what passes for interest in modern art circles, were a scrunched-up sheet of perfectly ordinary, blank typing paper, and a hunk of plasticine stuck to a wall. In their joint statement on this year’s winner, the Turner Prize judges gushed, “The lights going on and off have qualities of strength, rigor, wit and sensitivity to the site.” The communications director for the Tate gallery said Creed’s latest work was “pure and spiritual” and that Creed himself was “a very pure extreme kind of artist. The fact that many people find his work so baffling indicates that he’s working on the edge.” Columnist John Derbyshire points out the flimsy non sequitur at the base of such commendations: “It’s obscure, so it must be profound. You can get away with that in the visual arts, but not in literature, where ‘obscure’ only ever means one thing: badly written.” The ever-charmless pop star, Madonna, officiated at the gala presentation of Creed’s prize, ad-libbing that Work 227 was a work which “spoke strongly” to her and that what it said most strongly of all was that “Martin Creed really has balls”. But was the occupied or unoccupied status of Creed’s scrotum ever in doubt? The fact that the reliably trashy Madonna was chosen to host modern art’s biggest single night on the British calendar should tell you everything you need to know about the board and judges of the Turner Prize, and their priorities and commitment to art as something more important or meaningful than mere faddishness. A few days after the big gala, another British artist, Jacqueline Crofton, hurled a few harmless eggs into Creed’s empty room where they were quickly cleaned up. She did this specifically so she’d be hauled before the police and perhaps get an opportunity to speak to the press, which, bless her heart, she did, with courage, insight and a burning sense of injustice. I expect she spoke for millions of people all around the world – artists and patrons alike - when she told the Evening Standard: “What I object to fiercely is that we’ve got this cartel who control the top echelons of the art world . . . and leave no access for painters and sculptors with real creative talent. All they’re interested in is manufacturers of gimmicks like Creed.” I was so glad that it was an artist who perpetrated this harmless assault and followed it up with a well-reasoned announcement. Had it just been some ticked-off taxpayer who resented the whole notion of public art patronage on principle, it would’ve been too easy to brush it off as an Archie Bunkerism. While Jacqueline Crofton still deserves to have a special medal struck in her honour for daring to yell out that the poor addled Emperor has been wandering about in the buff for years now - and good luck Ms. Crofton in applying now for arts grants through any of the usual channels - I believe there are signs that perhaps a corner is already starting to be turned in this regard. Consider this. In a cute little pass that no one saw coming, a major career retrospective of the American magazine illustrator, Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), is the featured attraction at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City right now. No fleeting novelty or aberration, this travelling exhibition opened last October and runs until March 3rd. More incredible still, these whimsical and patriotic images of boy scouts, soldiers and other small-town American archetypes who might have wandered onto Rockwell’s canvases from some lost episode of Andy of Mayberry, are drawing the kind of crowds the Guggenheim hasn’t seen in years. Originally known as New York City’s Museum of Nonobjective Art, the Guggenheim built its reputation by mounting wildly unconventional, ground-shifting exhibitions by American avant-garde expressionists such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. The equally non-traditional building itself was designed by American architectural legend, Frank Lloyd Wright, with an exhibition area that is queasily laid out along a continuously spiralling ramp. So what gives here? How can this museum, dedicated to the artistic principles of tearing down the walls, up-ending the floor and shaking off the shackles of traditionalism, now be hosting this elaborate celebration of perhaps the most conventional and zipped-up American who ever picked up a brush? Some smarty-pants pundits argue that from the perspective of your typically wigged-out modern art curator, corny old Norman Rockwell who was snubbed and mocked in fashionable circles throughout his entire career, is about as far out as you can go. So in a perverse and reactionary sort of way, the Guggenheim tradition of stretching the boundaries of what’s “acceptable” continues. Even less convincing is the argument that attributes the show’s popularity to the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center. The unwashed hordes currently pouring into the show are supposedly seeking the artistic equivalent of a Mickey Mouse night-light whose heart-warming glow will soften the jarring uncertainties of this troubled time. Neither argument holds up. This retrospective has been touring lesser American cities for two years now and was booked into the Guggenheim long before a handful of suicidal terrorists had even enrolled in flying school. Furthermore, the non-objective or nonrepresentational art that the Guggenheim historically exhibited has been falling sharply out of public favour for the past ten years at least. The Guggenheim booked this show because they badly needed a blockbuster. Whether you care for his work or not (I don’t, much; too many cats and kids with freckles), only a snob would deny Rockwell was a crackerjack craftsman with a genius for depicting nuances of human expression and posture. His images have taken up permanent residence in the popular imagination in a way that Pollock’s strangely anonymous fields of splotches never could. One of Rockwell’s more sentimentally restrained canvases is the 1950 Saturday Evening Post cover called Shuffleton’s Barbershop which depicts a darkened barbershop with light spilling through from a back room full of amateur musicians. Yes, I know, this one has a cat in it too, but look beyond that for a second or two and marvel at some of the detailing and how exquisitely he captures the different gradations of light.This 1950 canvas predates and surpasses the work of many of the celebrated photographic realists who would only emerge more than a decade later. Though he was able to console himself with the truckloads of money he earned, Rockwell still felt the sting of rejection by his peers and the chattering connoisseurs of high culture. His major blunder – critically and socially – was that not only did he create sturdily representational work in a day when abstraction and subjectivism ruled, but far, far worse, he was an illustrator who strove to illuminate someone else’s story or else tell a story of his own. It’s interesting to leaf through any comprehensive history of Western art while considering this modern phobia regarding work that illustrates a story. Take away those works which illustrate or allude to some story from the Bible or mythology, Shakespeare or world literature, or which seek to record some dramatic moment in world history, and I daresay we’ve just jettisoned – minimum – one half of our civilization’s visual artistic legacy. It seems a strangely limiting aversion for any culture to maintain. I mean, what would we have left? Particularly un-evocative still lifes, deadly dull landscapes, Israel Mora’s jars of chizz and Martin Creed’s interminably flickering lights. Perhaps it was brought on by the development of photography, moving film and near-universal literacy. Taken together, these may have caused a few generations of artists to wonder if there was any longer any point in using their skills to reference stories. But stories are the eternal human hook. We’re drawn to pictures and images because we’re curious about what they’ll show us and tell us. What’s going on here? Why is this so beautiful or sad or horrific? What will happen next? For the would-be taste-shapers of the art world to so stridently denounce such a natural and satisfying appetite for the better part of a century strikes me as a rather virulent form of neurosis that badly needs to be sent packing. But Norman Rockwell got off lightly compared to the American illustrator whose work I particularly wish to focus on this evening in the second half of my talk, N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945). Wyeth’s bold and brilliantly executed canvases can still be seen today – twelve to twenty of them per volume – in reissued, illustrated editions of dozens of classic adventure stories such as Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, Kidnapped, David Balfour, and The Black Arrow, James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of The Mohicans and The Deerslayer, Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Island and Michael Strogoff, modern retellings of the Robin Hood and King Arthur stories, Jane Porter’s The Scottish Chiefs, Arthur Conan Doyle’s The White Company, The Bounty Trilogy by Nordhoff and Hall, Charles Kingsley’s Westward Ho!, Mark Twain’s The Mysterious Stranger, James Boyd’s Drums, Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle, Marjorie Kinnan Rawling’s The Yearling, and Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. The first and still most celebrated of these commissions came his way in February of 1911 when the publishing house of Charles Scribner’s Sons paid him $2,500 to illustrate Treasure Island. With that money the 29 year-old Wyeth bought land adjoining his house in Chadd’s Ford Pennsylvania and built the hilltop studio where he would work for the rest of his life. Wyeth had completed a long apprenticeship with illustrator/painter and writer, Howard Pyle, mostly doing magazine work. The working relationship with Pyle had become less than psychologically healthy by the end, thanks to Wyeth’s lifelong propensity for wildly idealizing his mentors and placing himself in degraded subservience to them. But the struggle with Pyle was a walk in the park compared to Wyeth’s cowering relationship with his mom. He had a mother complex as big as a Winebago and not too surprisingly, it powerfully emerged in some of the Treasure Island illustrations. In perhaps his single most celebrated canvas, we see Blind Pew, pitifully abandoned by his buccaneer comrades, tapping his way down the road in search of our young hero, Jim Hawkins, perhaps to rip his heart out and eat it raw. Writing of this painting, Wyeth biographer David Michaelis observes: “The horror of sightlessness is intensified by the diamond-sharp clarity of the winter night. Through Jim’s eyes we confront the blind beggar under a bright-as-day moon on the lane outside the Admiral Benbow Inn. Tapping with his stick, calling out in a voice “cruel, cold and ugly,” Pew gropes for us from the dark recesses of his cape with an enormous outstretched hand. Not only do we experience the thrill of confronting a predator up close but we have the grisly satisfaction of absorbing every detail of one who would like to catch us but cannot.” In the background we see the Admiral Benbow Inn where Jim lives with his newly widowed mother who is now depending on the boy totally to restore security to her life. None too subtly, Wyeth painted an exact likeness of his own parents’ house, which had been painstakingly built to his mother’s specifications, to represent what is supposed to be a seamen’s inn on the Devon coast. This is not going to be an easy house for Jim to break away from, as it never had been for Wyeth. In a spectacularly moody painting of Jim taking leave of his mother, Wyeth took a single sentence from the text about Jim saying goodbye to his mom, and blew it up into a major tragic scene of mother-wrenching loss. We see a guilty looking Jim stepping into shadow on a brilliantly bright day as his mother weeps into her hands in crestfallen abandonment. It is hard to overestimate the advances in illustration that Wyeth accomplished in the Treasure Island pictures and carried forward in the dozens of book commissions that followed, single-handedly taking the illustrated book to a whole new level of artistic accomplishment and sumptuous presentation. For one thing, these weren’t quickly tossed off pictures. Wyeth worked big. Massively big. Printed up in the books, his full, single page paintings measure six and a half by five and a quarter inches. The end-paper paintings at the front and back roughly double those dimensions. What you see in the books has usually been miniaturized from the original canvases by 98%. A lot of people have mentioned that his illustrations have a highly dramatic, even cinematic, “you are there,” quality. And it’s interesting to note that when Hollywood eventually made a film of Marjorie Rawlings’ The Yearling, in the year after Wyeth’s accidental death, the director took his cue for many of the scenes directly from Wyeth’s 1939 paintings. Starting with those first Treasure Island pictures Wyeth stated that it was his goal to present the story in such a way that his young reader “sees, hears, tastes or smells nothing but what (the main hero) did.” Before Wyeth, the standard approach in book illustration was to show the hero in every picture and, by framing as much of the action as possible, let us completely see what was going on. Of the seventeen full paintings for Treasure Island, only six actually picture Jim, making it easier, Wyeth hoped, for the reader to project himself into the story as a surrogate for Jim, so that “the reader is actually the boy at all times.” Wyeth earned a good living from those commissions and was completely engaged in such work while it was on his easel. “My conceptions are fuller, more significant,” he typically wrote when pushing through one of his illustrating assignments after months of poking away on his own work. “I do things with more authority – put statements down with a clear knowledge and directness.” Significantly, Wyeth’s massive letters home to Mother, which could clock in at a bulky 39 pages when he was at loose ends and feeling insecure, would unfailingly diminish to scrappier, often paint-smeared notes when he was in the thick of a book commission. All the Robert Louis Stevenson books evoked particularly strong work. Other particularly noteworthy efforts hail from his King Arthur, his Robinson Crusoe and his Robin Hood. An intense and loving husband and father, Wyeth was forever working his family and friends into his paintings. His wife Carolyn was featured repeatedly, my own favourite being the one where she stands in for Maid Marian in a scene of Robin Hood’s first meeting with his beloved. Again and again between these book assignments, Wyeth bought the critical line about the artistic worthlessness of illustration and succumbed to nothing less than self-loathing anguish. The books paid well enough that he could at least believe that he had sold out his artistic soul at a pretty good rate of return. He would come off such commissions with six or eight clear months ahead during which he would torture himself by slaving away at half-hearted, non-illustrative works that simply didn’t marshal his energies and instincts in the same compelling way. It’s appallingly sad to look at the magnificent work he accomplished as an illustrator and to realize that its creator felt like a fraud and a second-rater.

Wyeth’s horrible self-doubting was only compounded late in his life when his son Andrew, his star pupil who virtually lived in his father’s studio while growing up, immediately won the sort of lavish critical respect which N.C. had never garnered in his lifetime. Andrew’s very first New York show sold out and he’s never had to look back since. Ask your average American today to name a living artist, and the odds are good that Andrew Wyeth (or even Andrew’s son, Jamie) will be the name that springs to mind. I like Andrew’s stuff fine, though I do find it a little bleached out and gloomily ponderous. Jamie’s got a more vivid sense of colour and a livelier imagination. But I still insist the real Wyeth master is good old N.C. A few weeks before Wyeth died, Andrew vainly tried to reassure his dad about the value of his legacy. “I told him that he didn’t realize what he had done: He’d reached a pinnacle in illustration that would live forever. And I hoped that he would not look down on it. I got off my chest all the things that I felt about his work, the kind of things you never get a chance to say to people. He was very moved but he tried to fluff it off. I got mad. I said: ‘Do you realize what you’ve painted? The pictures you’ve painted are going to live way beyond all these modern artists that you look up to.’ He didn’t think what he had done in illustration was worth a damn.” Wyeth didn’t buy it. I wonder by that point if even a show at the Guggenheim would’ve convinced him? Writing in the Wall Street Journal last month, critic Terry Teachout, was commenting on what appeared to be the popular rediscovery and revalidation of aesthetic beauty in the wake of September 11. While commending the return of representational work to many New York galleries this fall and the renewed enthusiasm for concerts featuring such solid classical workhorses as Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis, Teachout called for caution. “At the same time, it's essential not to fall into the trap of neophobia, the error of assuming that nothing new or challenging can possibly be beautiful. That way lies the reactionary paralysis of those modernity-hating fogies of all ages who can't tell the difference between Schoenberg and Stravinsky and want all new buildings to be in the Beaux-Arts style and all new paintings to tell a story.” I would second Teachout’s proviso with enthusiasm; insisting that nothing I’ve said tonight promotes the rejection of thoughtful, skilful, non-representational work. I know that such work often has great value, and that it, in turn, has difficulty being acknowledged today when so many of the prizes and grants are seen to be routinely awarded to the sloppiest, most skill-deficient and sensation-seeking artists around. It seems to me that a welcome sign that a fair and rational equilibrium had finally been achieved in this matter would be if we allowed the best work of talented illustrators to qualify for possible admittance into our great pantheon of worthwhile art. Needless to say, my first candidate for such a reappraisal would be none other than Newell Convers Wyeth.

1 Comment

Max Lucchesi

10/9/2021 01:43:26 am

Herman, good stuff but it has left me a little confused unless it's your usual attack on the liberal luvvies of the art world, or sympathy for N.C. Wyeth's unhappy state of mind. $2.800 in 1911 for a first commission is worth about $80.000 today. Probably more money than Van Gogh, Modigliani and Gaugin earned together in their lifetimes. All 3 until their deaths were regarded as crap. Not that I compare either Mora or Creed to them:- not even in my wildest flights of fancy. Rockwell brilliantly portrayed an America that only existed in the imagination. Maybe his renewed popularity stems from America's nostalgic desire to return to those mythical 'good old days'. That fine illustrators were somehow considered ersatz artists will come as a surprise to Beatrix Potter (1866-1943), Wanda Gag (1898-1946), Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966). Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898) and a host of others whose work is still exhibited and revered. Over the last 10 years of this Tory Government, Arts Council funding is 30% of what it was. Channel 4, the lifeline of independent film makers will be privatised. By the end of next year the British Council must shed 2000 jobs and close its offices in 38 countries. Lets not mention funding for school art classes or grass roots cultural activities. Will you shed a tear, or think about Mora and Creed?

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed