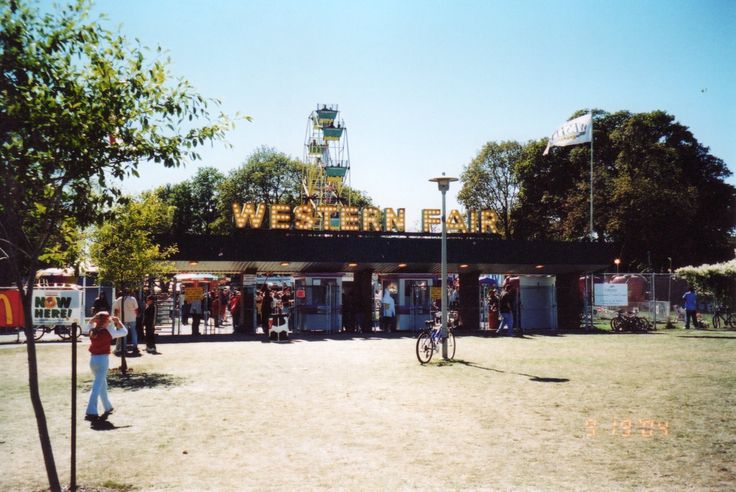

LONDON, ONTARIO – In this first full week after Labour Day, I’m grappling with a sudden sense of loss as – for the first time in my entire life – I am not having to torture myself with the question, “Should I try to get out to the Western Fair this year?” Thanks to the Wuhan batflu pandemic, the Fair is sitting out 2020. I really do ask that question each year even though, I’m a little ashamed to admit, I haven’t answered it in the affirmative so far this century. I’m never happy to stay away but with no young kids tugging at my elbow to burn up a hundred and fifty dollars on violent rides and dodgy food like elephant ears and corndogs, and with the winnowing out of so many of the traditional rural attractions that had increasingly beguiled me as an adult, the thrill and charm of the Western Fair has largely evaporated for me. Attendance numbers at the Fair have been plummeting for more than a decade and mothballing it this year for the sake of the batflu, isn’t likely to do any favours to its momentum if they even manage to cobble together some kind of revivified exposition next year. I hope I’m wrong but I fear that the end is drawing nigh for one of London’s most hallowed community traditions and that next year’s early September question might well be, “Why didn’t I go to the Fair when I still had the chance?” Early on, of course, the big attraction for me was the rides. In our tenth summer me and my best friend, Beezer, devoted our entire summer to raising as much money as we could for our Fair Funds. Every allowance, the avails of every lawn-cutting job, stray coins I found on the sidewalk or dug out from underneath the cushions of our couch – all of it was diligently hoarded. I remember finding an empty Coke bottle on the front lawn of Mountsfield Public School across from our home, cycling the four blocks to the variety store to cash it in and returning to drop the two pennies thus accrued into the repurposed honey jar where I kept my loot. I don’t know if I’ve ever felt so loaded as I did on that Saturday afternoon when my Dad drove Beez and me down to the King Street gate and set us loose like princes of the midway. A couple decades later it was annual visits to the barns that provided the most solace to the soul. Stroking horse muzzles, snorting with the pigs, sharing deep-drowning eye contact with Jersey cows or bleating lullabies to the sheep as they tucked down for the night in their Ku Klux Klan pyjamas – all served to remind me that there was a whole sustaining universe of agricultural activity out there which we urbanites are all too likely to take for granted and ignore. Geographically, it may be ‘out there,’ but psychologically, it’s just behind us and beneath us. Most families don’t have to go back too many generations to find their farming forebears. It’s impossible to believe that all those centuries of planting, growing, herding and harvesting haven’t left behind some instincts and reflexes, some deep racial memories which were mysteriously stirred on these annual visits. By sheer happenstance my wife and I made it out to the Aylmer Fair in 2015 where we took in – equal parts engrossed and appalled – our very first demolition derby. There was also a rather exotic petting zoo where I enjoyed my first ever one-on-one conversations with a zebra (the design of whose coat was eye-wateringly beautiful) a camel and a standoffish llama. And just off the midway in a sort of enormous Quonset hut, there were agricultural displays (including gargantuan pumpkins and artfully arranged stooks of Indian corn) and perhaps a dozen large display boards covered with submissions to a children’s art contest. It was a little like slipping through a time warp and spending an evening at the fair as I used to know it half a century ago. The Western Fair has been around for what seems like forever. One year younger than Canada itself (this would have been its 152nd edition) it lights up old East London for only ten consecutive days. Its limited duration is part of what makes it so useful as a marker of change, a measuring stick we can apply to our lives. But just as important that way is the fact that it begins on the first weekend after Labour Day when we’ve packed up another summer and commenced a new grade in school or returned to work and there is this strong and universal sense that it’s time to get down to business as our world begins another annual cycle. I’ve long contended that if we ordered these things properly, we would celebrate New Year’s in that first full week in September instead of the depths of winter when absolutely nothing around us is changing. Back in 1950s London, the Western Fair was just about the only consolation when returning to the regimented tedium of school. That first Tuesday back, along with the various textbooks and supplies your new teacher handed out, there was also one ticket granting a free child’s admission to the Fair, always bearing on the front a picture of the Mounties’ Musical Ride, a highlight every year at the Grandstand. In recent years the Fair backed off in its always futile attempt to get big name celebrity acts. It seems to be a rule of fairs that they can only afford newbies who have yet to make a name for themselves, or has-beens in their descent. I always felt that cornier, old school acts like barber shop quartets and magicians and tumblers were a much better fit with the spirit of the Fair. In 1981, wearing his firstborn child in a Snuggly on his chest, my brother Ted (whose stained glass window of a Western Fair scene is on permanent display at the Fred Landon Library) caught a troupe of lady Taiwanese acrobats in a matinee performance on the Grandstand. Ted was totally mesmerized when one of them scaled up the body of another and flipped herself up into a headstand with no hands bearing any of the weight; the crown of her head pressing down onto the crown of the lady underneath. This extraordinary, difficult and undoubtedly painful feat which these women had travelled halfway around the world to perform was all but ignored by the paltry audience who happened to have wandered onto the grandstand in the middle of the afternoon. Suddenly overcome by the cruel contrast of the artistry and grit of these performers and the utter indifference of that handful of spectators, Ted surprised himself by starting to cry like he hadn’t done since he was a child. Ted allows that he was undergoing the stresses that any new parent experiences such as regularly disrupted sleep and financial anxieties and these too could have acted as triggers for his tears. I also expect he might have been feeling some progenitor’s remorse: What kind of thankless world have I brought this child into? Baked into the Western Fair as I knew it a generation or two ago were numerous visions of just what a hard slog life could be. In my very earliest visits they still had the sideshow tents where you paid a nickel to gawk at misfits and freaks of nature. The fat lady looked real enough. I wasn’t as convinced of the veracity of the bearded lady, the dead Siamese twins who were displayed in a big jar of brine (I was pretty sure they were plastic dolls whose heads had been melted together) or the man who had “alligator skin”. Outside of those tents one encountered more miscellaneous human oddities such as the metallic-voiced huckster hawking veg-a-matics to a wary and cynical crowd . . . the surly sap who’d just lost his entire stake on playing games of chance . . . the poor lady running the cotton candy stall who tried to flick a wayward wasp out of the spinning drum of pastel-coloured sugar and pulled out an arm stickily bearded in baby blue floss . . . the anxious mother who plopped her firstborn on her very first ride in Kiddieland and then couldn’t bear to leave the child’s side; cooing inane reassurances as she trotted around this gentle ride’s circuit for a couple dozen revolutions.  My mother, a lifelong Londoner, adored the Western Fair and would attend once in the evening with our family when the emphasis was on the midway where my three brothers and I would sample as many rides as we could and then she would go again on some long and empty weekday with two or three of her friends, visiting all of the buildings with their displays of new products and appliances that had minimal appeal for fellas. The only ride Mom always went on was the Caterpillar, the bar-none tamest ride outside of Kiddieland. As the youngest of her children by almost four years and the most averse to violent rides that just spun you around in myriad ways until you felt like you were going to vomit, I was the last Goodden she could reliably persuade to go on this rickety old conveyance with her. It was the last ride on the midway with a wooden deck from which you would step down into a commodious roller coaster-type car, all of them linked together in a chain. But there were no steep hills or sudden drops on the Caterpillar. This thing moved around a sensible circle at a sensible speed on a track that barely and gently undulated. Its only thrills and chills were supplied by a sort of black, canvas canopy that would swing over top of each car so that you were riding in darkness. At least, that was the original effect. By the time I started riding on it with Mom, that canopy was riddled with holes and tears that let in so much light that I could see the sheepish look on her face when I asked in a decidedly unimpressed voice, “So what’s the big appeal with this ride, anyway?” The Caterpillar’s been gone now for at least forty years but every time I go to the Fair, I linger by the patch of property it used to occupy, recalling it and my mother as I cosily marinate in one of the chief pleasures the Western Fair reliably provides – an achingly rich sense of life’s fleeting impermanence and also, somehow, its stubborn continuity. I suppose this sense was considerably deepened in my twenty-second year when I landed a job on the Fair’s cleanup crew and got a glimpse behind the glitzy facade. I’d show up around 11 each night of the Fair as the last stragglers were heading out and work on the grounds through to dawn, removing empty cups and half-eaten candy apples from decorative flowerpots and spearing and sweeping up garbage and litter from the midway and the lawns in Kiddieland. This site I’d always associated with bustling crowds and dazzling coloured lights was all but abandoned and darkly monochrome; a little ‘spooky,’ as Dame Edna Everage would say. A couple times through a shift, particularly if it was cold or rainy, I’d duck into the St. Anne’s Church food tent where they served coffee and tea around the clock and you could warm up your hands by rubbing them together in the vicinity of the steam-gushing urns. You knew the end of your shift was drawing nigh when, cloudy or clear, the chorus of roosters in one of the livestock barns started calling up the sun. Before too much longer this shadowy graveyard of a fair would start to spring back into its gloriously gaudy and improbable life. I know I haven’t been its most avid supporter these last twenty years but this September without a Fair has reminded me of the delights – homespun and garish – of what I’ve been ignoring. If it can find a way to pull off its phoenix-like act once more, I pledge to drop by for another look.

2 Comments

Ted Goodden

15/9/2020 01:34:43 pm

Thanks for this article, Herman, which has left me envying your night job at the fair. It also unleashed a deep file of memories...The Fat Lady, who was referred to by the barker as "A Quarter Ton of Jolly Fun!", was in fact a very sad woman who sold tiny Bibles- no bigger than a 5 cent matchbox- for fifty cents each. The St. Anne's Church pavilion was an oasis of sanity in the midst of all the hucksterism and gaudy attractions; they also made it their mission to provide down-home meals for the agricultural gang and working staff at the fair. Their raisin pie, with a scoop of vanilla ice cream, has been added to the menu in Heaven.I believe they continue to make and sell these pies from their church on Commisioners Road.

Reply

Dan Mailer

3/10/2020 11:41:57 am

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed