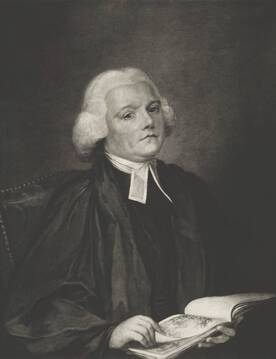

GILBERT WHITE DRINKING IN BIRDSONG GILBERT WHITE DRINKING IN BIRDSONG LONDON, ONTARIO – “It is I find in zoology as it is in botany; all nature is so full, that that district produces the greatest variety which is the most examined . . . Men that undertake only one district are much more likely to advance natural knowledge than those that grasp at more than they can possibly be acquainted with; every kingdom, every province, should have its own monographer.” – Gilbert White in "The Natural History of Selborne" (1789) The English parish of Selborne straddles the border of Hampshire and West Sussex. The main road which runs southwest from London to Portsmouth cuts through its eastern section. It was within this twelve square mile patch that clergyman and naturalist Gilbert White (1720–93) made all the observations about birds, animals, plants and human beings which make his only book, twenty years in the writing, such an inexhaustible delight. It was particularly birds – specifically swallows, swifts, martins and thrushes – which bewitched and enchanted White. While his observations are meticulously rendered, they are never clinical or sterile. And while his theories are usually postulated with real rigour and care, there is nary a paragraph in his Natural History which isn’t shot through with a grateful Christian’s awe at the miracle of life on earth in all its myriad type and form. The 19th century poet and essayist, James Russel Lowell, suggested that a subtitle for White’s opus might be The Journal of Adam in Paradise. Modern day ecologists see in The Natural History of Selborne a pioneering sensibility calling mankind to a more enlightened stewardship of our natural environment; a recognition that the well-being of humans and the wildlife around us is all of a piece.  Gilbert White (1720–93) Gilbert White (1720–93) Certainly by modern standards, there was a little too much poetry and wonder in White’s heart to always keep him on the scientific straight and narrow. Most notoriously, he had a hard time believing that his beloved swallows could possibly migrate all the way to Africa in the winter and so he concocted some wholly unsubstantiated theories that at least some of those beautiful birds stayed behind each year and toughed it out for the chilly duration, tucking down under particularly deep hedges, taking refuge in the oozy marshlands or nestling into the warm thatched rooves of Selborne cottages. Perhaps on some level he knew that he was spinning moonshine here but he wouldn’t entirely let go of this whimsy even in the face of ridicule. Quite simply for Gilbert White, it seems to have been unthinkable that Selborne should ever be utterly bereft of swallows, even in the coldest depths of winter. And so he hatched this goofy yet oddly touching fantasy of at least a few rogue swallows-in-hiding. But setting aside an indulgence such as that – and also allowing that nobody really picks up his Natural History for its cool objective acumen – White’s book did actually score some uncontested scientific firsts. It was White who first distinguished the weasel from the stoat, who first charted the migrating patterns (if not the precise winter destinations) of many different birds, who listened closely enough to discern regional differences in birdsong, and it was White who first determined – a discovery to quicken the pulse of any English clergyman – that swallows regularly enjoy the double delight of copulating in mid-air.  Iona Opie (1923–2017) Iona Opie (1923–2017) “Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home, / Your house is on fire and your children all gone.” The ladybird obeyed, as they always do – and yet it always seems like magic; and we were left wondering about this rhyme we had known since childhood and had never questioned until now. What did it mean? Where did it come from? Who wrote it? – Iona Opie in "Tail Feathers of Mother Goose" (1988) A couple centuries after Gilbert White, childhood anthropologists and anthologists, Peter and Iona Opie, lived a few miles down the highway from White’s Selborne home. The remarkably prodigious couple made their first big splash with The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren (1959); a study they produced to counter the speculation that mass media was eliminating regional variations in children’s dialects and vocabulary. Worthy follow-up studies included Children’s Games in Street and Playground (1969) and The Singing Game (1985). As well the Opies researched and pulled together material for a half dozen Oxford anthologies of nursery rhymes, fairy tales and poetry for children. Peter died in 1982 and eleven years later, Iona produced her last really significant work, The People in the Playground which synthesized her gleanings from thirty years’ worth of eavesdropping and interviewing visits, once a week during recess to a primary school in nearby Liss.  Peter Opie (1918–1982) Peter Opie (1918–1982) Peter Opie talked about that later book of Iona’s when he was interviewed by Jonathon Cott in 1981: “Iona goes down to the playground every single week and notices when a game starts and when it finishes in season. And it’s exactly what Gilbert White was doing with the birds and animals in Selborne. He was the first person to look at these creatures in their natural environment and wonder how they worked and where they fed, and then he wrote down what was happening day after day. In his notebooks White noted when the children started playing marbles, but as far as we’re aware, nobody has watched the children in a village week after week, year after year, in order to say whether or not games appear seasonally.” Whenever I dip into Iona’s book, I recognize that Selborne playground as a universal plot, remembering my own Forest City playgrounds from sixty years ago. It was all there. The breathtakingly vulgar poems and jokes; the new game that wins currency in the yard for a few weeks, growing more elaborate and complex until nobody can stand it anymore and someone ‘invents’ the next one; the ever-shifting allegiances and animosities; the never-failing complications and ruptures when the sexes wander onto one another’s consciousness and turf. In one of my favourite bits, Iona writes, “The girls wanted me to write down evidence of the boys’ iniquity. ‘Write down, we don’t like boys. Boys have got fleas. Put, boys swear and they are all horrible, and boys are dumb.’ The sweetest of these indignant females said, ‘The boys really smell. They stink. They make us feel sick,’ and then she looked up at me sideways and said, ‘Are you a detective? Mandy wanted to know’.” Like Gilbert White before them, the Opies were detectives; self-educated, self-directed sleuths who developed their own field of specialty and discovered “that that district which is the most examined produces the greatest variety.” My wife worked lunch hour duty at Empress Public school for a few years when our kids were all attending there and was repeatedly astonished at how the themes which rippled through our adult lives – be they personal, social, occupational or political – all turned up in only slightly modified form, usually sooner than later, in the churning human kaleidoscope which formed itself into arresting new patterns every day on that half acre plot. That reverence which veterans and historians feel for certain battlefields – that sense that something sacred has been invested here at great cost – I’ve always instinctively felt for playgrounds. If only this hard-pummeled earth could talk. British broadcaster and writer, Richard Mabey, who specialized in tracing the influence of nature on culture, was, naturally enough, a fan of both Gilbert White and the Opies. At least twenty years ago I scribbled down this observation from one of his many books and monographs in which he contends that when we remove weeds from playgrounds and lawns, we deny people, particularly kids, a way of learning about the natural world, about human history and folklore: “There are over twenty different species of wildflower (excluding grasses) on my lawn, many of them just those plants through which, in children’s games, we have our first physical intimacy with nature: dandelion seed-heads for telling the time . . . buttercups under the chin, Lady’s slippers and clovers to suck for nectar. These flowers are part of children’s lives precisely because they are weeds, abundant and resilient plants that grow comfortingly and accessibly close to us.” In that interview with Jonathon Cott, Peter Opie described his and Iona’s work in childhood anthropology in the same sort of terms, drawing attention to the ground on which they happened to be standing: “We just look further and further into our own little patch.” This delving ever deeper into the local in search of the universal, into the immediate in search of the eternal, suggests the mysticism of William Blake in his often quoted poem, Auguries of Innocence. To see the world in a grain of sand And heaven in a wild flower, Hold infinity in the palm of your hand And eternity in an hour. Institutionalized education can have a dulling effect on those brilliant flights of imagination, enthusiasm and love which are the hallmarks of the curious amateur and the child. Gilbert White and the Opies didn’t need a university chair or anything special in the way of equipment or resources to conduct their fascinating – and fascinated – work. Ultimately it is the quality of the attention we bring to whatever it is that draws us, which most determines the value of our discoveries.

2 Comments

Jim Chapman

1/2/2021 12:10:25 pm

I had no idea anyone had conducted such research into the world of playgrounds. Thanks for shedding some light on this fascinating subject.

Reply

Max Lucchesi

2/2/2021 02:51:59 am

I too remember a different world Herman. As a 19 year old in 1961 it took me and my best friend Bernie over 2 days to drive from Basel at the Swiss/French border to Chiasso at the Italian border. Today it takes 5 hours. 0nly Germany had Autobahns in those days, though Italy had begun it's Autostrada del Sole. I have seen the fishing villages from the coast of Eastern Turkey to the Atlantic tip of Western Spain become an endless continuation of high rise hotels. You can now buy cornflakes even in the dukan of remote Himalayan villages.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed