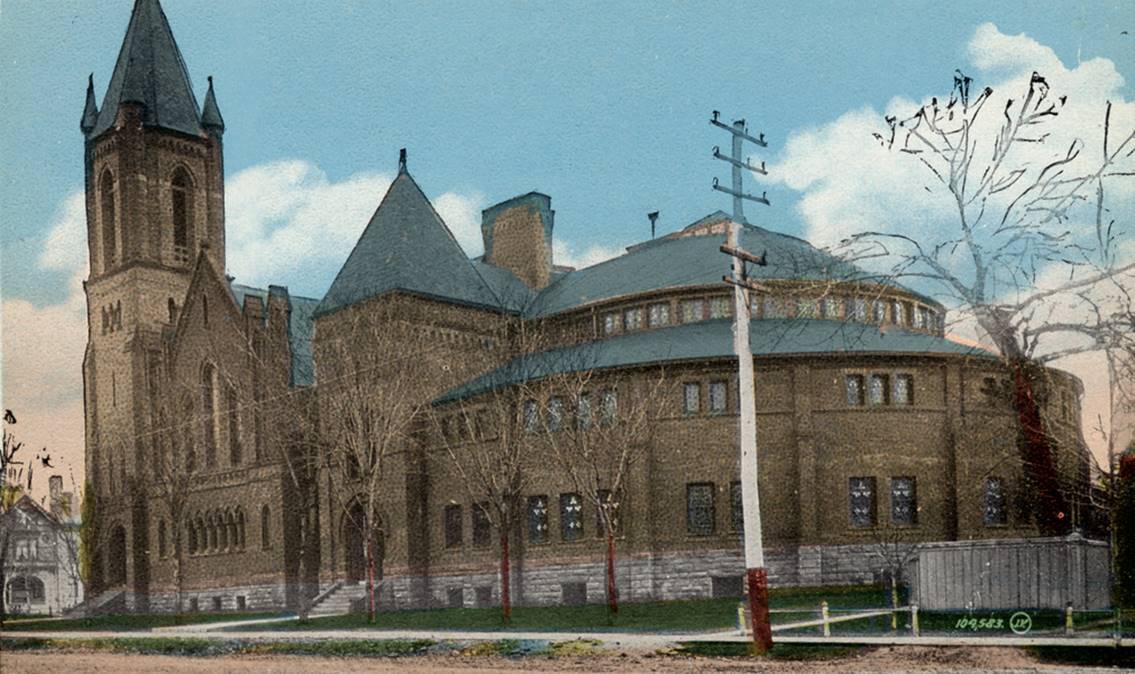

Reverend R. Maurice Boyd (1932–2009) Reverend R. Maurice Boyd (1932–2009) LONDON, ONTARIO – When the Reverend Maurice Boyd (1932–2009) died in New York City at the age of 77, it scarcely caused a ripple here in London where twenty years before he had occupied our most prominent pulpit; serving as the senior minister at Metropolitan United Church from 1975 to 1988. The inspired oratory of this very dynamic preacher had built up that downtown congregation to the largest of its kind in the entire country. I thought it was particularly shabby when Boyd’s successor at the (by then) seriously depleted Met, Robert Ripley, didn’t see fit to even mention his illustrious forbear’s passing in his inane Free Press column that ran every Saturday. “Ah, perhaps that explains it,” I thought a few years later when Ripley threw over his ministry and his faith and came out as an atheist. No small part of the Irish-born and trained Boyd’s appeal during his London years was his principled opposition to the leftward drift of the United Church. In the pulpit and in the press he forthrightly denounced what he regarded as his church’s lax stand on principles of sexual morality and the sanctity of human life. In protest against that drift he cancelled his congregation’s longstanding subscription to The Observer, the national magazine of the United Church. In the early ‘80s when I was actively seeking out a church to belong to, I attended the Met quite frequently. Boyd’s stellar reputation aside, this was a natural enough choice for me as the United Church was the denomination I had inconsistently attended at my parents’ behest as a child. There were three services at the Met every Sunday. And at their best, Boyd’s sermons were as stimulating as a good university lecture, chock full of quotes from English mystics, poets and preachers like John Donne, George Herbert, William Blake and Leslie Weatherhead; all of it firmly grounded in the 2000-year continuum of Christian thought. At their infrequent weakest, one sometimes felt they had been battered about the head with a copy of Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations for half an hour and struggled amidst all those dropped names and references to discern just what it was that Boyd himself was trying to say. I thought about joining the United Church from time to time but something always held me back. Though I couldn’t name it yet, there was always something crucial that was missing at those services; something more important than an intellectually probing sermon; something I wouldn’t discover until Boyd went away on his usual summer-long sabbatical and, repelled by the numbing tone and content of his substitute sermonizer, I was driven into St. Peter’s Cathedral Basilica in downtown London on Labour Day weekend of 1983. The sermon or homily that night was unremarkable but everything else felt so completely right that immediately following mass I signed up to take instruction in the faith. I first interviewed Boyd early in 1985, almost a year after I’d been accepted into the Catholic Church. Boyd said to me, “Now I’ll tell you something – and it’s something I’ve told my congregation as well – that when his holiness the Pope came to Canada this summer, he came for me too. And many of the things he said I’ve found more strengthening than many of the things the moderator of the United Church says.” With a less powerful figure the church hierarchy might’ve tried to knock Boyd back into line but that clearly wasn’t going to work here. His national pre-eminence as a preacher was reflected in his many invitations to fill guest-preaching slots in churches across the country, in Britain and the U.S. When the Welch Publishing Company introduced their Canadian Pulpit Series of books, Boyd’s sermon collection entitled A Lover’s Quarrel with the World (edited by Ian Hunter and introduced by Malcolm Muggeridge) was the premiere edition. Boyd always regarded preaching as his primary ministerial role and if he didn’t devote the better part of each working week to thinking and writing, Boyd felt that his sermons would not have been so meaty and challenging.. “That is my first priority and I’ll not allow anything to intrude on that,” he told me in that 1985 interview. Even at his peak of popularity, some parishioners were troubled that Boyd left so much of the pastoral work (such as visiting shut-ins, the bereaved and the hospitalised) to his junior ministers.

Other people bristled when he insisted on clearing the sanctuary of children before delivering his sermons. No small part of his uncanny effectiveness as an orator was his theatrical flair. The lilt and contrasting inflections of his voice, the dramatic pauses – all these would’ve been sabotaged by the sound of fidgeting kids or crying babies. I wondered what Boyd would make of the impromptu church service I heard about that was thrown together in the discombobulated wake of the Oklahoma City bombing and when a baby's cry rent the air as the minister was about to speak, he deferred to the infant, saying, "There's the only voice we all need to hear today." Boyd had done some guest preaching at New York City’s Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church (the pre-eminent Presbyterian pulpit in the world) in the summer of 1986 and made a very strong impression. When that church went looking for a new senior minister in 1988, they shoved aside the 400 applications and resumes they had received for the position, and instead asked Boyd if he would accept the job. Thrilled at the chance to have “a voice in New York, the crossroads of the world, where so many visitors from all over the world are present each Sunday,” he accepted the call. “That’s a very exciting prospect and I want to preach there for the remaining years of my ministry,” he told me. The day when I interviewed him about his imminent departure for New York, Boyd had to attend to a lot of other duties and details so that it was already 6:00 or 6:30 by the time we concluded and Boyd suggested we nip over to a nearby pub and grab some supper. I was all for that and looked forward to having a less formal and less guarded chat with a man I admired very much. By the time we parted, I admired him less and was filled with foreboding about what might lie ahead for him. Three things stand out for me from our talk. The innocuous one was that he ordered the “mixed grill” – the first time (in my admittedly limited experience of restaurants) I’d ever heard of that particular entrée which I’ve ordered many times subsequently and never without thinking of him. The second thing was how impossible it was for me to hold his attention or focus. I suppose I might have been a particularly dull dog that night and a dud of a conversationalist but it was rude of him to show it so consistently after inviting me out to dinner. Every time somebody passed by in the general vicinity of our table, his eyes would wander toward them and the air would go hissing out of whatever subject we were pretending to discuss. I couldn’t figure out if he was hoping that somebody else would recognize him or worried that they would. Either way, it really bugged me. But the third one was the doozer. I asked him about two marriages involving friends of mine and parishioners of his which had recently bitten the dust. One of them appeared to get dissolved quite 'amicably' as they say. In the other case, the wife did not go quietly into that matrimonial recycling bin. I asked him about these fractures, seeking some sort of pastoral insight into how the best-intentioned people, married in a Christian ceremony that was rich in significance for them, could skid off the rails so completely. I may have phrased my question poorly, but I will never forget his answer. “The classy ones don’t make a scene.” “I beg your pardon,” I said, disbelieving I’d heard what I heard. “When a marriage has run its course,” he reiterated, “the classy ones accept it without making a scene.” I wouldn’t expect a more spiritually barren insight into the agony of divorce from the cheapest quickie lawyer. Boyd's glory years in New York turned out to be very few. Yes, he was enormously popular at first and the quality of his preaching soon swelled the membership rolls at Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church by a third. Then, early in 1992 he came to loggerheads with that church’s elders over the same old issues; most particularly his single-minded commitment to preaching above all his other ministerial roles. Rather than submit to in-house correction and counseling, he abruptly resigned. The New York Times reported on January 13, 1992, “Amid astonished gasps, angry tears and cries of ‘Don’t go! Don’t go!’ the Rev. R. Maurice Boyd told a stunned congregation, ‘I will not preach here again’. “After giving him a standing ovation, hundreds of worshipers lined up to say goodbye to the pastor, who has served as senior minister to the 2,700-member church for the last three and a half years, bringing in almost 900 new members. While the conflict around the charismatic minister had lasted for months, the resolution took most by surprise. The roots of the conflict appear to be complex. Some church elders were growing increasingly hostile to Mr. Boyd's frequent speaking engagements outside his own church, viewing him as more concerned with his own reputation than with building the church. And growing tensions between Mr. Boyd's supporters and opponents in the church leadership led to what one congregant described as a ‘management crisis’." In the wake of that meltdown Boyd started up his own breakaway congregation the following year. The City Church of New York, meeting each Sunday in rented premises owned by the New York Society of Ethical Culture, operated from the spring of 1993 to the spring of 2007, though never with more than about 400 members. London friends who continued to acquire cassettes and CDs of some of his later sermons reported that references to God or Christ markedly fell off and references to himself and the craft of sermonizing inversely increased. “They seemed to be more about self-improvement than sermons,” one of these friends said. Somewhere during this period he quietly divorced his wife and the mother of his children (who, we can hope, kept it classy) and remarried. It was a low-key, obscure and rather eccentric finale to a career that had once promised – and indeed, delivered – so much. As I tumbled the question, “What happened?” around in my head after learning of Reverend Boyd’s death, I recalled American Catholic writer Flannery O’Connor’s (1925–64) answer to a fan who wanted to know why nearly all of her weird and grotesque characters, from the most secretive brooders to the most raving fanatics, were Protestants. O’Connor answered: “To a lot of Protestants I know, monks and nuns are fanatics, none greater. And to a lot of monks and nuns I know, my Protestant prophets are fanatics. For my part, I think the only difference between them is that if you are a Catholic and have this intensity of belief, you join the convent and are heard from no more; whereas if you are a Protestant and have it, there is no convent for you to join and you go about in the world getting into all sorts of trouble and drawing the wrath of people who don’t believe anything much at all down on your head.” O’Connor found that the firm and clearly delineated creed, and the rich multiformity of Catholic worship had a way of accommodating, transforming or answering almost any dilemma that a Catholic might encounter in the course of life. And wonderfully reassuring and sustaining as this was for her, it didn’t make for the kind of drama O’Connor required in her stories. Stark old Protestantism, on the other hand, was always drawing such props and traditions out of the way, changing the rules of membership and throwing the believer back onto nothing more than his own instincts and the vitality of his own private relationship with God at this very moment. The tragedy I ultimately construed from the story of Reverend Boyd’s career is that I don’t think he ever served an institutional church whose divine authority he could trust and thus he himself was hobbled. As deep and sincere as his faith was, and as rare and compelling as his oratorical gifts were, he never was part of a church that he could sufficiently honour and respect so as to submit to its tempering influences. I am sometimes asked by friends how I can stand to remain in a Church that is increasingly fixed in the public imagination as utterly riddled with rot and is currently headed up by glib-talking virtue signalers who see their primary mission as finding ways to conform the Church to a fallen world. But then I think of a newly separated Maurice Boyd hanging out his shingle at the Society of Ethical Culture and saying, “Hey, let’s do this whole church thing my way,” and I am not tempted to bolt for even one second. The history of Christianity is replete with instances when the appeal of making a clean break becomes irresistible and a whole new church gets set up on what is perceived to be more adaptable and responsive foundations. There are moments when it might seem like a great idea, a tremendous relief, to not be loaded down with all that dead history and unnecessary baggage, all that maddening connectivity to the place where it all began. But in any moment that’s connected to eternity – as all moments in Church history are – separation only pushes you to the sidelines. As wildly dysfunctional as the Roman Catholic Church may be right now, her history is anything but dead, and her saints are alive and proclaiming their good news to anyone who can hear their sermons amidst the bawling of all those babies. Properly perceived, a lot of her attendant baggage is shot full of meaning and beauty and, as it all turns out, is essential to both our sanity and our survival. And .- no small point this - she also happens to be the only truly enduring home that any of us will ever know.

2 Comments

Max Lucchesi

1/10/2021 12:24:54 am

Herman, you give the impression the Rev is a well read and intelligent version of that other gentleman of the old Ulster school; the Reverend Ian Paisley. Another preacher in love with the sound of his own voice. I agree with Ms. O'Connor but would add a caveat about both types of loonie. A Catholic sinner who truly repents can obtain absolution, for the Protestant sinner there is only damnation. Though lately they can be thrown into a pond and be born again (several times even! Calvin and Knox are turning in their graves). A couple of things I have found on my travels are, conservative of all religions have one thing in common. That sanctity of life like human rights are not universal but only apply to the deserving. The other is that most preachers preach or sermonise at their parishioners while the best few preach for their parishioners. Sadly most parishioners feel the more fire, brimstone and fear of hell thrown at them, the better be their souls.

Reply

Susan Cassan

6/10/2021 10:19:37 am

Max, I am astonished. It has been rather a long time since my Roman Catholic friends in Elementary School solemnly assured me that despite all my repentance and efforts at reform, I was damned without the intervention of a priest. As I was a Lutheran, I was familiar with the doctrine of Grace, and hence was able to withstand their attempts to unsettle me. Surely you are not at one with my school mates, convinced all Protestants are condemned?

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed