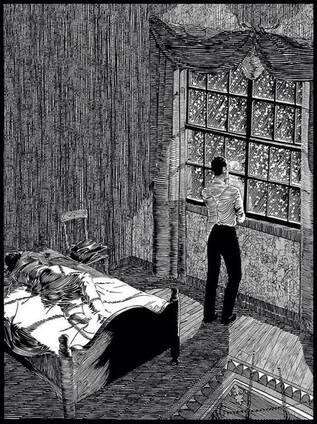

LONDON, ONTARIO - My grudge against the claustrophobically belligerent year of 2020 lightened considerably in its very last week when the meteorological elements presiding over this patch of the globe summoned the grace to deliver a substantial and transforming snowfall on Christmas Eve. That generous blanketing was augmented over the next twelve days with a few more dustings and falls so that even a bout of freezing rain wasn’t enough to significantly diminish the white bounty that was still in place for this week’s close of Christmastide on the Feast of the Epiphany. With its sublime knack for slowing and quieting everything down, snow has a way of sharpening our senses and broadening our perceptions; as does Christmas itself when we take the time and the care to observe it well. Some may think this lessening of my grudge against a pitiless year for so whimsical a reason marks me out as a too readily forgiving soul. And these are probably the same people who roll their eyes in scoffing dismissal whenever they hear the commonly expressed - and almost as commonly crooned - wish for a White Christmas. It may seem like sentimental hooey but there are sound religious reasons for longing for snow in this achingly tender season. Silent and subtle in its approach and accumulation, we are often caught unawares by its sudden physical presence. You look out the window and gasp a little - you had no idea this was happening. That element of delighted sabotage alerts us to other apprehensions of divinity and eternity which have their best chance to take hold of us at this time of year and yank us out of our usual cognitive routines. Snow somehow primes us for unexpected revelations, reminding us that there are much larger games afoot in our universe than those which ordinarily monopolize our attention. Whenever I have to shovel the stuff from our sidewalks and driveway - even on a seriously socked-in day when I am called outside for a second or third shift to re-disperse yet another inundation - there comes a moment when I stand still to straighten my back for a bit and catch my breath. Hands resting atop the handle of that stationary shovel, I raise my eyes and look around and can't help marveling at the supernatural beauty of a taken-for-granted world that has been so magically renewed. In such moments more strident passions that sputter away on the surface of life are effortlessly calmed, My resolve to look farther into the mystery of things is deepened and I tell myself to try to resist states of mind so fevered that I fail to remember what a gift it is to be here at all. Anyone who's taken in such blessings over these last few weeks, will now be better prepared to resume however much of our day-to-day lives as our overreaching civil authorities think we can responsibly handle. No writer did a finer job than James Joyce (1882-1941) of delineating the sort of snow-driven epiphanies that I’m describing here. The entire trajectory of Joyce's career was played out in what I believe was a not very helpful attempt to win some mental clarity by shaking off his most formative influences of Ireland and the Roman Catholic Church, But once he fled his Emerald Isle roots to hunker down in various European locales to compose his not terribly large oeuvre of three increasingly eccentric and abstruse novels of Christ-haunted Irish life, it became apparent that the only place this most relentless of exiles ever really resided was deep inside the memory-soaked folds of his own brain. While I actually bailed on his final novel, Finnegan’s Wake (I was getting so little out of it that I couldn’t see the point in continuing) and skimmed whole sections of the frequently exasperating Ulysses, I attended to every word of his first novel, The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and rather detested its unsavory egoism, even while admitting and admiring Joyce’s visionary powers. He really is an extraordinarily immersive, one-of-a-kind writer. But the only one of his books I return to for pleasure is Dubliners, an even earlier volume of short stories, which is crowned by what I regard as his masterpiece, The Dead. Clocking in at fifty pages, some scholars contend that The Dead should be properly classified as a novella. Director John Huston struggled for decades to scrape the funding together to film The Dead, finally getting the go-ahead in the last months of his life in 1987. It was quite fitting that this should be Huston's final film and it was made under heroic conditions, with the director confined to a wheelchair and trailing a tank of oxygen, speaking through a respirator mask as he set up shots and counseled his cast of actors which included his daughter, Anjelica, in the only movie they ever worked on together. Otherwise the extraordinary cast which he assembled for The Dead was comprised of veteran stage actors with zero name or face recognition outside of Ireland, If the film was ever screened at a London cinema, it must've been in a week when I was otherwise engaged. I didn't catch up with it until Boxing Day of 1995 when I saw it on TV. Commercials and all, it was shatteringly good; the kind of movie that takes up permanent residence in your subconscious from where it spontaneously deals out indelible images or lines or expressions on characters' faces whenever some chiming echo is rung by an encounter or event in your own life. My regard for the story wildly revived, I reread The Dead the next day and was cornering friends over the holidays, making them listen to the elegiac music of its concluding pages. It didn't work its magic on everyone. Some people found it to be nothing more than depressing. The Christmas of 1995 had been disspiritingly green and London remained snowless until noon on the Eve of the Epiphany when a grand eighteen-hour deluge got underway. My brother Ted and his family used to host “Pudding Parties” (as they called them) on the Twelfth Night and our trudge across the bridge to his home on The Ridgeway that evening was a considerable slog. I was standing around in the kitchen with several other guests at one a.m. waiting for the coffee to perk when composer Oliver Whitehead pushed aside a curtain on the back window to peer out into Ted's yard. "I think we could say that snow is general all over Western Ontario," he pronounced, echoing the final paragraph of The Dead which also happens to be set on the Eve of the Epiphany. I laughed out loud in delight but to this day I rather regret that I didn't take him in my arms and kiss him. Joyce's tale is told in the third person but everything is seen over the shoulder as it were of Gabriel Conroy, a provincial college teacher and book reviewer back in Dublin for the holidays. He has taken his wife Gretta to the dance and feast which is held every Twelfth Night by his two aging aunts and their younger assistant who are music teachers. Gabriel is feeling thoroughly middle-aged and mediocre and is troubled by the failure and pettiness written on the faces of his fellow guests; nearly all of whom he knows a little too well. He is also haunted by the absence of a few great souls who’ve recently passed on and whose presence could’ve done much to elevate the tone of this year’s soiree above the tired and the tawdry. When he stands up to give his annual toast to his hosts – "the Three Graces of Dublin" he calls them – he’s appalled at what a fatuous old smoothie he’s become and is further saddened to see that his hollow words have brought grateful tears to the eyes of his aunts. Leaving the party, Gabriel scoots on ahead to the cloakroom to fetch his coat and boots and then looks up and sees his wife transfixed at the top of the stairs by the song of a shy student who couldn’t summon the courage to sing his ballad until the guests had filed out of the main room. Watching his wife poised on that staircase, one hand gripping the banister as her ears hungrily drink in every melancholy note, Gabriel desires her in a way he hasn’t known in years. They hail a horse-drawn cab which takes them along the river in the falling snow back to their hotel, where Gretta tells him why she found that song so moving. It reminded her of a frail young suitor who had loved her when she was seventeen and used to sing that very same song. Gabriel is about to express his jealousy when Gretta tells him the boy is long dead. Michael Furey was already ill when Gretta was preparing to leave for convent school but he braved harsh weather to come see her one last time. “I implored of him to go home at once and told him he would get his death in the rain. But he said he did not want to live. I can see his eyes as well as well! He was standing at the end of the wall where there was a tree.” This utterly scotches Gabriel’s amorous mood and his wife then falls asleep in inconsolable tears, confirming his sense of himself as a half-alive soul even when compared to the ghost of the once-passionate Michael Furey. “He stretched himself cautiously along under the sheets and lay down beside his wife. One by one they were all becoming shades . . . He thought of how she who lay beside him had locked in her heart for so many years that image of her lover’s eyes when he had told her that he did not wish to live. Generous tears filled Gabriel’s eyes. He had never felt like that himself towards any woman but he knew that such a feeling must be love. The tears gathered more thickly in his eyes and in the partial darkness he imagined he saw the form of a young man standing under a dripping tree. Other forms were near. His soul had approached that region where dwell the vast hosts of the dead. He was conscious of, but could not apprehend, their wayward and flickering existence. His own identity was fading out into a grey impalpable world; the solid world itself, which these dead had one time reared and lived in, was dissolving and dwindling. “A few light taps upon the pane made him turn to the window. It had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight . . . Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly on the Bog of Allen and, further westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling too upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.” When he finished writing the stories gathered together in Dubliners, Joyce really seems to have believed for a while that he'd kissed off/kicked out Ireland for good. But of course he never was able to do that. And over that Christmas of 1995 I was in the grip of a similar sort of paradox which my viewing and rereading of The Dead had really stirred up. Just a few years before - in 1992 - I had lost three key figures in my life, each of whom had died way too early; my father-in-law, William Jarvis, who had become almost as important to me as a benevolent elder as my own father; Fraser Boa, a wildly inspiring teacher of theatre and film who went on to become my analyst and helped me sort out my callings as both a husband and a writer; and the artist, Greg Curnoe, who I didn't know so intimately as the others but who had greatly influenced my understanding of the opportunities given and the challenges posed to anyone trying to eke out an existence while making art in London. The Joycean paradox I was wrestling with that Christmas - and it wasn't a troubling paradox but I did fear that it might yet prove itself to be too good to be true or too sweet to last - was that, yes, I'd helped to bury all three of these men but in so many powerfully consoling ways, they were not gone from my life. Of course it couldn't happen face to face anymore but from time to time - and not just in dreams - I was still having something very much like conversations with all of them. Indeed, I don't think I'd ever learned so much from Greg than in the months immediately following his death. After I got home from Ted's Pudding Party I took Ben our fearless border collie out for his evening ablutions in the half-frozen Thames River. The snow was still falling as larking students across the way in Harris Park just north of Eldon House, tobogganed down one of the steepest hills in London on requisitioned cafeteria trays, unknowingly acting out one of my own favourite stunts from half a lifetime before. On this particular night, that too felt like a kind of ghostly apparition even though, as far as I could determine, that was not me in spectral form on the other side of the river; I was still here - very much alive, alive-o - and deeply thankful to be so. I decided it was the presence or absence of a sacramental view of life which makes people alive to the spiritual wonder which drenches Joyce's story, or only cognizant of the depressing litany of death and decay which is gleaned by a more scientific reading. Anyone with even a wobbly sense of history or religion knows that death may mark the passing of a being's physical presence on this earth but that in myriad, meaningful ways, no one utterly dies. The great Catholic writer, G.K. Chesterton - the universally acknowledged Emperor of Paradox - laid out the dynamic here brilliantly, pointing out that if you want to be fruitfully haunted by the dead, then you must invite them into your life by paying them some sort of homage or tribute: "Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about." One often hears from particularly myopic empiricists who tell us we should resent the interference of what they blandly call "the dead hand of history" in our ongoing human affairs. Traditionalists of every stripe and Catholics - who, lest we forget, pray for the dead every day in their conviction that it is all of the saints of every age who make up the living membership of the Church - know better than this. As do lovers of James Joyce's finest short story. We know that when properly perceived, that hand of history is profoundly alive and is always at work in our world as a force of wisdom and guidance if only we will take hold of it. And far more often than not, if you look around on those occasions when that hand does reach out to you, it also happens to be snowing.

2 Comments

Max Lucchesi

5/1/2021 11:29:19 am

Herman, no regular reader of your posts would ever accuse you of being readily forgiving. Whatever forgiveness you measure out is strictly rationed. As a 20 year old I loved Portrait and Dubliners, struggled like you with Ulysses and Finnegan's Wake, though had a better understanding of that " stream of consciousness " thing after I read Knut Hamsen.

Reply

Ninian Mellamphy

6/1/2021 11:22:00 am

As I read Herman's reflections on snow-shoveling I wondered what his Australian readers would have thought of his meditations. But soon I realized that he was preparing us for his thoughtful analysis of "The Dead," and I knew that even the Australians would have admired the trick.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed