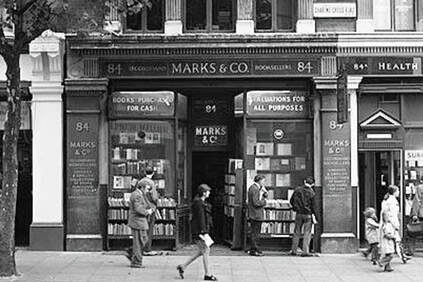

Marks & Co, Books, 84 Charing Cross Road Marks & Co, Books, 84 Charing Cross Road LONDON, ONTARIO – One of Hermaneutics’ Britain-based correspondents – the one who makes other readers ask, “If you disappoint him so much, why does he keep reading you?” – sent me a note this week inquiring whether I’d ever seen the 1987 film that was made of Helene Hanff’s 84 Charing Cross Road. I had indeed and his twigging made me watch it again. I’ve also read the original book and seen the stage play which was adapted from the book as well. In all of its forms the real-life story is built around the decades-long correspondence between Hanff, a struggling script writer based in New York, and the staff of an English second-hand bookshop who fill her orders for worthy editions of classic books that cannot be so readily (or cheaply) procured in the States. Though I actually find the Hanff character a little too New Yawk brassy for my tastes, in any of its iterations her tale does capture the thrill of the chase that drives any avid reader from one great discovery to another. And her tale also portrays the fascination we denizens of the new world feel for the manners and efficiency, the quality control and the scholarship, and the snug-as-a-bug-in-a-hidey-hole charm that are manifested in the best British shops. My correspondent's note (and revisiting the film) made me realize with a start that it will be nine years this May since I’ve known the pleasure of trawling through the nooks and shelves of a great antiquarian shop like St. Philip’s Books in Oxford. I had plans to get over last fall until the freaking Wuhan Batflu shut down the globe. Then yesterday after Mass – oh yes, our beneficent overlords are letting us back into church at thirty percent capacity again so long as we promise not to sing – we removed our stupid masks and basked in a patch of sunlight with two friends who told us (fingers crossed) that if things keep opening up like many are projecting they will, then they’re hoping to fly over to Britain this fall. Gosh, what a sweet possibility that set kindling in our hearts. It also sent me rooting through my files for some accounts of past bibliophilic expeditions to that enchanted isle. DECEMBER 2000 / WHEN I WAS IN ENGLAND in 1993 with our firstborn who was then 12 years old, I was usually able to confine my really tedious ports of call (in her eyes) to those times when she would be off doing something else that actually appealed to her. There was only one day – our last full day together in London – when all my careful planning broke down and there was nothing else for it but to drag her around with me as I went burrowing through the book shops of Charing Cross Road and Cecil Court. It was not my proudest moment as a father. I lied to her. ("Just one more shop and I'm done.") I bribed her. ("Give me ten more minutes and then we'll find a place that sells milkshakes.") I made rash promises that I didn't know how I'd fulfill. ("Look, these shops will be closed soon and then we'll do something you want to do.") When she looked down one of the side streets off Charing Cross Road and saw the St. Martin's Theatre promoting The Mousetrap, we both knew that we'd found the perfect payoff. The St. Martin's is just across the street from The Ambassadors where The Mousetrap premiered in 1952 and it was able to switch theatres without interruption in 1974. We paid eight pounds a pop for seats to that night's performance in what they call the "Upper Circle" – the steepest, most cramped and precarious balcony I've ever perched on. The St. Martin's is beautifully appointed with mahogany panelled walls, brass fixtures and a rather stunning leaded glass dome in the roof. But the place looked like it hadn't been dusted since The Mousetrap opened there – or at least the tops of those surfaces visible from the balcony hadn't been. We Upper Circle dwellers had our own entrance off a side alley and never got to see if things looked any brighter or cleaner from the ground floor perspective. To call The Mousetrap a creaky contrivance of limited ingenuity that runs its eight stereotypical characters through a series of hackneyed hoops . . . would be a tad harsh but true. Richard Attenborough in the original cast as Detective Sergeant Trotter, remains the only actor who's ever risen to prominence as the result of appearing in this show. For all subsequent actors, The Mousetrap represents a kind of . . . well, a mousetrap. It's good steady work with lots of cheese but realistically speaking, where does one go from here? Is any film or theatrical agent going to come calling because of the brilliant reviews you've been garnering in this unkillable relic? Other than hordes of tourists, who's even going to see your work? And these camera-toting rubes haven't come to see a play so much as they've come to wondrously gawk at another British institution like the Tower of London or Madame Tussaud's. And boy, are they ticked off when they see signs posted on every wall telling them not to take pictures but to fork over another four pounds for the commemorative Mousetrap souvenir booklet. The play itself is as wheezy and cosy as Christmas dinner with your favourite antiquarian relatives. The artificial snow piles up on the window ledges of Monkswell Manor, cutting off eight virtual strangers from the outside world. When dear Mrs. Boyle gets strangled in the dark and turns up dead on the hearth-side rug at the conclusion of Act One, we know that one of these absurdly affected eccentrics – each of whom we're simultaneously growing to enjoy and suspect - has to be the murderer. The Mousetrap isn't a particularly effective mystery or play, so much as it is a living museum exhibition; an utterly unchallenging and strangely reassuring relic of British post-war theatre. Everything - from the crackly gramophone quality sound of the incidental music, to the ushers selling ice cream from a tray at the interval – bespeaks a more innocent, leisurely and credulous time. It provides a wonderful holiday from twenty-first century stress. MAY 2002 / BUNGAY, ENGLAND – Visiting Cambridge nine years ago, I admired a heroic statue of Alfred Lord Tennyson in the foyer of Trinity College Chapel. Twenty minutes later I was across the road in one of that university town's many great bookshops and, my interest recently piqued in Queen Victoria's favourite poet laureate, I pulled down a hefty biography of Tennyson and started laughing when the book fell open to a frontispiece featuring a full page photograph of the very same statue. “What's so funny?” my fellow browsers were too polite to ask, though they subtly scuttled away from me while studiously pulling their own books up closer to their faces. If they had asked for an explanation, I could only have said, “Bear with me. I'm just in from one of the colonies and am a little overcome to be finally standing at the centre of the English literary universe. We don't get experiences like this very often in London, Ontario.” In England these epiphanies can happen virtually anywhere and can leave you reeling a little as layer after layer of connection and coincidence is revealed. Take the other day, for instance. I took the train out to Cambridge, passing through the flat and marshy fens where the novelist and ghostly short story writer, L.P. Hartley (1895–1972) lived for most of his life. For reading on the train I took along Adrian Wright's 1995 biography of Hartley, Foreign Country, which I'd picked up at a second hand shop a day earlier in Norwich, about a twenty-minute drive from the town where I'm staying. I was reading about Hartley's rapturous appreciation for Ely Cathedral (Hartley's faith, such as it was, seemed to be ninety-nine percent driven by his love for church architecture) just as that soaring edifice pulled into view, dominating the landscape for miles around. Wright's title hails from the first sentence of Hartley's best known novel, The Go-Between: “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” Many will have seen the excellent film adaptation from 1971 starring Julie Christie and Alan Bates. The Go-Between tells the story of a middle-class schoolboy named Leo who is invited to spend a month in the country at the home of his much wealthier friend. When his friend is quarantined with chicken pox for a couple of weeks, Leo is taken under the wing of his friend's older sister, Marian, who soon gets him running letters of romantic assignation between herself and the hunky tenant farmer who works on their estate; even though she is supposedly betrothed to a nobleman. Leo has developed an innocent crush on Marian and undergoes his own guilty and awkward sexual awakening when he realizes what these two are up to and his own pivotal role in facilitating their doomed affair which transgresses all laws of morality and class.  A still from 84 Charing Cross Road (1987) A still from 84 Charing Cross Road (1987) Just outside Bungay on the road to Norwich is Bradenham Hall, a palatial country pile which was the home of H. Rider Haggard (1856–1925) the author of such high hokum, imperialist fodder as King Solomon's Mines and She (from which John Mortimer borrowed the timorous handle by which his fictional barrister, Rumpole of the Bailey, refers to his overbearing wife: “She who must be obeyed”). Hartley's sister has told the story that when her brother was about ten, he was invited to summer with a school friend whose coal-merchant family had leased the home from Haggard who had left the country with his family in tow for a Grand Tour of the Holy Land. It was Hartley, not his host, who came down with chicken pox and while strictly confined to his bedroom, he came upon some journals in a cupboard where one of Haggard's daughters poured out her heart about her thwarted love affair with one of the tenant farmers, and railed against the tyranny of her father for dragging her away to the other side of the world until things cooled down. Hartley may not have served as anybody's go-between but that summer he began to apprehend the explosive potentialities of love and the way in which conventions of propriety and class could blight all prospect of happiness or freedom – even for the well born. The information so surreptitiously gleaned that summer burbled away in his subconscious for forty years, not emerging to public view until 1953 as the framework around which he constructed his masterpiece. Tomorrow, God help me, I go down to London, where such overlapping stories turn up a dozen to the block. JUNE 2002 / THIS WEEK I RETURNED to Canada from my fifth visit to Britain in twelve years and if only I could arrange and afford it, I’d turn around tomorrow and go back again. I’ve long believed that in a well-regulated life, a trip to Britain should be an annual event. Is this so very surprising? Between my Welsh-born father and my Irish-descended mother, consider the geographic compulsions of blood and genetics yanking me across that ocean with magnetic irrefutability. As one of those tiresome boomers, the giddy excitement of Beatlemania constituted the dawning of my musical consciousness. Hungry to know more about the culture that spawned such infectious music, I quickly started to absorb other forms of British music, literature and visual art: “Come on down Ralph Vaughan Williams, George Orwell and David Hockney.” That vista then deepened as I followed each of those traditions further backward into the past: “Come on up Orlando Gibbons, Samuel Johnson and William Blake.” Of course, this process is inexhaustible: “Come out, wherever you are, oh Venerable Bede, whoever that geezer was who first wrote Beowulf, and that band of crafty engineering Druids who somehow assembled Stonehenge.” Always I stagger home with an unconscionable load of books and recordings to finesse through customs lest I get dinged for extra baggage. The first days back are racked by wild yearnings to immediately return to England. My emotional and geographical turmoil is worst when I first come to in the morning, shaking off disorienting dreams and swimming upwards to the light before I know with any certainty just where in the world I am. Then I have to firmly remind myself that holidays are not real life and that the England I periodically visit with such unencumbered enjoyment is not a place I could afford to live. Neither can a lot of the people who do live there. While the economy has improved from its terrifying trough ten years ago, Brits complain they’re working ever faster and longer just to tread water. The swarms of homeless people tucking down each night on the stone stairways of inner city churches certainly aren’t getting smaller. The bus and rail systems, recently privatised, are dangerously strained and seem in danger of collapsing altogether. Seven commuters died in a train crash at Potters Bar the second week of my visit. A year and a half ago, a similar crash in Hatfield killed four commuters. In Canada such appalling lack of diligence would cause systems to be shut down while improvements and alternatives were developed. But England can’t afford to stop. The very next day, London commuters detoured around Potters Bar, but otherwise everybody was back on the tracks and in the tube, hanging onto overhead straps as they read newspaper accounts of the tragedy. One fears the next such collision will come sooner than later and will be met with even less outrage. On my last night in London, returning from a concert of Rachmaninoff’s Russian Vespers at Westminster Cathedral by the Bach Choir, I shared a tube ride with a homeless woman. Our car was pretty full at first but soon emptied out as we rattled along from one station to the next, finally leaving us as the only occupants as we quietly glided into its terminus in the suburb of Ealing. She could have been forty or sixty years old and lay sprawled across two facing benches under a sign designating “Priority Seating” - reserved for the handicapped or mothers with babies. Her dress was shiny with age and frayed. Her coat was filthy and her hair all greasy and matted. On her feet she wore nothing but tennis shoes and her ankles were swollen and chafed. Clutched in one hand was a carrier bag full of papers and on her ring finger was a wedding band. Had she ever been married or had a baby? Was there nobody left to care about what she had been reduced to? In her imperturbable slumber, might she be dreaming of a better life in a land where people aren’t left to fall so completely through the cracks? If I’d wakened her to tell her what her country represented to me – that there was nowhere else on Earth where I felt so connected to art and beauty and the positive blessings of civilisation – would she have laughed in my face? MAY 2008 / FOR THIS, MY EIGHTH TRIP to Britain in eighteen years (but hey, who’s keeping count?) I switched the itinerary around a little – visiting two cities for the first time, another for my first extended stay and then, as usual, wrapping things up in London. I got about two minutes of tremulous quasi-sleep on the flight over with Air Sardine and found I was cruelly under-dressed for the kind of weather I thought I was leaving behind in Canada. God bless the Brits. They are so unprepared for snow and they said this mid-April blizzard was the most they’d had in Brighton all year. I saw one fastidious looking gent wielding his credit card as an inadequate scraper to remove slush from his windshield. Late in the season or not, most folks were delighted by the white stuff. I saw families and kids building snowmen in all of the parks and even out on Brighton Pier. What a preposterous white elephant of a town. There was a sign in one of the hotel windows advertising a big Quadrophenia convention this summer. Brighton was the site in the ‘60s of all those massive mod and rocker clashes so vividly chronicled in the Who’s second rock opera. Perhaps I should have foreseen the day when the town’s chamber of commerce would commemorate those youthful battles as a nostalgic tourist attraction. It does fit the pattern, after all. In a country that markets Vera Lynn’s old hits as Music of the Blitz and transforms the attempted destruction of Parliament into National Firecracker Day, I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised to see those forty-year old gang wars similarly sentimentalised into an occasion for generating a little more commerce. Brighton’s ditziness has a long pedigree, going back to the construction of George IV’s simultaneously breath-taking and laughable pleasure palace, the Brighton Pavilion. Commenting on its quasi-Oriental excesses richly topped off with a cluster of domes, eighteenth-century clergyman and wit Sydney Smith said, “It looked for all the world as if the Dome of St. Paul’s had come down to Brighton and pupped.” And, of course, as Queen Victoria noted when explaining why she hardly ever visited the place, this celebrated beachside pavilion doesn’t even face the water. After quick one-day visits on previous holidays that were intriguing but hardly captivating, I was able to stay in Oxford for four full days and have fallen in love with the place. Unlike Cambridge (or most Canadian universities for that matter) the campus is not solidly sequestered in one area but has colleges scattered all over the old town – some of them so discreetly identified, it’s easy to miss or confuse them. It takes a little longer to know where you are here but once you grasp the interconnectedness of town and gown, you see how this symbiotic relationship has profoundly enriched the entire community. Many of the most exquisite parks, manicured and rough, are owned and jealously protected by the colleges in a way that no city department could ever pull off. The calibre of music-making in the churches is extraordinary and even the street corner buskers are classically trained. The finally glorious spring weather also helped soften my impressions of the place. The sun came out as I was walking through daffodil-strewn Christchurch Meadow en route to Magdalene College’s Addison’s Walk, where C.S. Lewis was all but converted to Christianity on a late night ramble with J.R.R. Tolkien. In crews of two and three and four, students messed about in punts on the canal. And deep into the meadow walkway, the only sound to be heard was birdsong. The entire world seemed drunk with the surging return of spring, I thought, almost laughing out loud when I happened upon a besotted young couple who couldn’t remain upright one minute longer and had impetuously collapsed into the nearest flowerbed to canoodle and neck. On my last morning in Oxford I attended Sunday mass at Tolkien’s old parish church at the Oratory of St. Aloysius Gonzaga. The joint was packed to the gunwales for a service that was simultaneously enthusiastic and reverent and the hymns by such eminent Catholic worthies as Thomas Tallis and William Byrd were so beautifully rendered that I almost levitated with bliss. I got into the medieval cathedral town of Lincoln in the eastern midlands on Sunday night and spent most of Monday kicking around inside one of the most impressive church structures on the planet. No doubt it was the contrast with what had been so impeccably observed the day before at Oxford that suffused this visit with sadness. The Church of England swiped Lincoln Cathedral from the Roman Catholics during the English Reformation and had a couple of good centuries but the unmistakeable impression is that things are winding down there now and they don’t quite know what to do with all the space. Everywhere you turn donations are beseeched to fix the organ, supply flowers and hymn books, or repair the building itself to the tune of one million pounds a year. Most of the two dozen or so people moving about inside to gawk at the windows, choir screens and tombs seemed to have no vital connection to the great supernatural drama that was so elaborately enshrined there. The cathedral lost a lot of goodwill when the powers that be rented it out for Ron Howard to use (in lieu of the Vatican which wasn’t for rent) in filming his surprisingly boring movie of Dan Brown’s goofy bestseller, The Da Vinci Code. Lincoln itself is one of the oldest towns in Britain with traces of the old Roman wall still evident and the occasional mastodon bone turning up in muddy bogs or riverbeds. It’s a landscape that compels you to draw a broad perspective – something the cathedral rectors signally failed to do when they sold the joint out for thirty pieces of silver. And as for London itself . . . More congested than ever (the streaming crowds in the downtown tube stations are enough to set off the claustrophobic heebie-jeebies), more spied upon than ever (closed circuit security cameras are simply everywhere), it still remains (along with New York City, Paris and Rome) one of the great cities of the world. But how will it ever contain the Olympics in just four more years? Note to self: Trip number nine must either precede or follow 2012. HA, AS THINGS TURNED OUT, trip number nine did indeed take place in 2012 about three months before the Olympics and mere days before Queen Elizabeth II got serious about observing the Diamond Jubilee of her coronation. And everything worked out just fine.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed