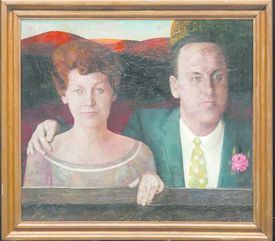

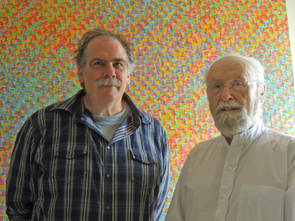

MARION & ROSS WOODMAN: Oil on wood painting by Jack Chambers, 1961. AGO, Toronto MARION & ROSS WOODMAN: Oil on wood painting by Jack Chambers, 1961. AGO, Toronto LONDON, ONTARIO – Our old friend Chris Aikenhead had no sooner greeted us as we touched down at Vancouver Airport on the first leg of our West Coast tour on Monday, July 9th, than he gently, gingerly asked if we’d heard the news out of London which we’d only left behind about seven hours earlier. Oh God, the dog-sitters had screwed up and Gracie got hit by a car? Kirtley’s mom had taken another tumble and we’d have to fly right back and stand sentinel at her bedside? “Marion Woodman has died,” he said and was perhaps a little miffed when we practically sighed in relief. “Don’t scare us like that,” I almost said but managed to repress it; starting to surprise even myself with my apparent unconcern about the passing of a teacher and friend who’d meant so much to me. Why wasn’t I overcome with grief? Well, Marion’s age was obviously a factor – 89 – the same age as my father and mother when they passed. Setting aside the shock one always feels when the reassurance of a loved one’s earthly presence is taken away, you couldn’t exactly say that she’d been robbed by the Reaper; that if only she’d been granted a little more time, whole new avenues of exploration might’ve opened up. Marion had enjoyed a good long life that was packed to the brim with accomplishments. And then I remembered that strange relaxation of anxiety I felt as my own mother died and her hand grew cold inside my own. With my mother it had been more than a decade of Alzheimer’s. With Marion it had been good old-fashioned dementia ravaging her magnificent mind for almost as long. In both cases I had been forced to come to terms with losing these wonderful women long before their hearts actually stopped. And then a few more weeks down the line, I could attest to another similarity with the passing of my mother. When the incremental and inexorable destruction of both these women finally ceased, so too did that maddening atmosphere of diminishment and mayhem that made their final years such a trial to witness. With the lifting away of that cruelly limiting filter, it became possible to regard all of Marion’s life afresh. In her dying, she had been paradoxically restored to me. IN MEMORIALIZING MARION WOODMAN (1928 – 2018) it will be impossible for me to speak of her without also talking about her youngest brother, Fraser Boa (1932 – 92), and her husband, Ross Woodman (1922 – 2014). My involvement with all three has been so deep and rich and thematically of a piece (though each brought with them their very own strengths, emphases and quirks) that to speak of any is to speak of all. I know that Marion would not object that her portrait is mingled with theirs. I remember the joy and pride on her face when I talked with her one afternoon on their stairway about how much we’d been enjoying Ross’ impetuous solo visits to our house, how our children adored ‘Uncle Ross’ who would often slip them money to go and see movies, and how Kirtley thrived with the valuable support and insight he gave her in her studio. “Isn’t he great?” Marion might’ve said in words; she certainly did with her beaming face. And, in a way, I’m only following her lead. At Ross’s funeral four years ago, already well mired in dementia’s debilitating grasp, Marion impulsively rose to her feet about a third of the way through the programme of eulogists to share a few memories of her husband which soon morphed into memories of her brother who’d died almost a quarter of a century before. It was twenty kinds of awkward at the time and more than a little heartbreaking that a woman who’d always had such poise and grace should now be undone by forgetfulness. And yet, once again, with the passage of time and the attaining of a little distance, that embarrassing slippage of gears now seems to bespeak a different kind of mindfulness which I am emulating here. I know that I’ll be leaping from one lookout point to another in these recollections; upstream, downstream, this bank or that bank, occasionally perched on a rock of my own in that very same brook in which this flow of incidents and events will be gliding along. This short poem by Emily Dickinson – Marion’s all-time favourite poet – might suggest the sort of ride we’re in for: Tell all the truth but tell it slant, Success in circuit lies, Too bright for our infirm delight The truth’s superb surprise; As lightning to the children eased With explanation kind, The truth must dazzle gradually Or every man be blind. – Emily Dickinson SO LET'S START WITH the happiest day of Marion Woodman’s life; or so she characterized it to me – the special party they threw for her in the spring of 1974 at South Secondary School to commemorate the premature retirement of a much-loved teacher of English, Theatre and Philosophy. For twenty-two intermittent years, Marion had been teaching at South and had briefly left the school on two earlier occasions. In 1962 she had spent a year in England with her husband, Ross, and in 1968 she retired from teaching to set out alone on a spiritual journey which began with a proposed tour of ashrams in India and culminated two years later in London, England where she went through analysis for one year with Dr. A.E. Bennett, a lifelong friend and colleague of psychological pioneer, Carl Gustav Jung. Following this analysis she had returned to South for what would turn out to be her final three years of teaching. Few people at that retirement party believed that this was really it. As a 22 year-old ex-student of Marion’s, I was asked to give a biographical sketch of our honoured subject and welcomed the assembled crowd to the “third official Marion Woodman retirement party”. (Two years earlier, I had delivered a similar talk for her brother when Fraser had quit teaching film and theatre to run a repertory cinema in Toronto.) Also discouraging public gullibility was Marion herself who walked among her friends that evening saying things like, “I absolutely love this school. I always have and I’d give anything to stay.” Asked what she planned to do after retirement, Marion answered, “I don’t really know yet.” Asked why she resigned, she would only say, “The time has come.” Though there were few she dared confess such a thing to at the time, her resignation had been prompted by a dream that had told her in no uncertain terms that the spiritual journey she had begun in 1968 needed to be resumed. At that moment she was still awaiting confirmation from the Carl Jung Institute in Zurich to which she’d applied as a student for the next term. The prospect of setting out on such a venture, alone, at this point in her life, was more than a little daunting. Her last three years at South had been her happiest and among her most productive, particularly in the realm of theatre, and there was much more she longed to do. “You always seemed so happy as a teacher,” the guests kept telling her and she couldn’t deny it. After the dinner, slides were projected on the cafeteria wall depicting the many milestones in her teaching career. Students from over two decades paid tribute to her work, scenes were acted from plays she had directed and a six-voice choir sang the Magnificat from William Byrd’s Great Service. “In a way, it was like being at my own funeral,” she recalled. “Not knowing what I was going to be born into, I had to admit that something behind me had just finished. That evening was the recognition of who I had been.” There was certainly a lot to look back on. THE FIRST BORN CHILD and only daughter of a Scottish United Church minister, Marion’s life was framed in a stark religious context long before she could understand what most of it meant. As a child she would host solitary tea parties in the nearby Anglican graveyard, setting out cups and saucers on the gravestones for the nourishment of invisible friends. Shortly after giving birth to Fraser, Mrs. Boa came down with tuberculosis. Although she eventually recovered and lived a long life, Fraser was mostly cared for by Marion, who liked to load the new infant into her dolly pram and take him out promenading. Once Fraser was capable of taking his own steps, Marion still called most of the shots, enlisting Fraser and their middle brother, Bruce, in elaborate re-enactments of the mysterious and archetypal rituals they saw all around them in the daily life of the parsonage. Minister’s kids are often pretty strange but the three Boas could be downright spooky. Mock weddings were often performed and funerals for dead birds, encased in empty chocolate boxes and transported to their resting place in a wagon draped in a Union Jack. Sometimes other children from the village would fall into line and accompany them in their procession to the cemetery. Marion also remembers hiding under the wooden pews in her father’s church, hoping to catch sight of God in his house. Sometimes the sun pouring in through the windows would heat up the pews until they began to creak which Marion, both fearful and delighted, would interpret as a sign of His imminent arrival. “Here He comes . . . This is it!” All three children tended to be serious and early on evinced a marked passion for theatre and literature. Bruce, who died in 2004, was the only Boa I didn’t know well; only meeting him once at Fraser’s funeral. In 1958 he began a long career as a character actor primarily based in England. His two largest audiences were amassed with his guest-starring role as an overbearing American tourist in the ninth episode of Fawlty Towers entitled Waldorf Salad and as Rebel General Rieekan in 1980’s Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. Fraser and Marion developed an amazingly mutual trajectory of almost 60 years duration – as brother and sister and as soul mates and colleagues – first as English and theatre teachers at South and then as Jungian analysts in adjoining offices on St. Clair Avenue West in Toronto. A BRIGHT AND PRECOCIOUS CHILD, Marion began studying for her degree in Honours English at the University of Western Ontario at the age of 16, at a time when most of her classmates were weary young veterans just home from World War II. She spent her first two years as a teacher in Forest and Timmins, teaching elementary students. For one of her very first assignments she was called in shortly after Christmas to replace a woman who had gone quietly mad on the job. One day the children were murmuring in excited tones and Marion couldn’t command their attention. Some of the children stood up and ran over to the window while others remained at their desks but stared in the same direction. Following their gaze, Marion looked out and there was her predecessor, standing outside in the gently falling snow and crying, waving hello (or was it goodbye?) to all of her former students, mesmerized by her loss. For Marion’s third year of teaching, she obtained a position in a school for slum children near the east end docks of London, England. Even before setting foot in her first class, the superiors at the school had told her quite plainly, “These kids are unteachable and we don’t expect them to learn a thing. Just find a way to entertain them for six hours a day and we’ll be happy.” Marion found this lack of illusion refreshing and said, “I learned something from those kids – I was unteachable too.” What Marion meant by this, and what she learned from that English experience, can perhaps be illustrated by talking with a friend of my older brothers who seemed to be well along the road to a life of delinquency until he came under Marion’s influence as an English teacher at South. He wishes to remain anonymous: “I was a rebel. I was what they called a shit disturber. With most teachers your reputation would precede you into the classroom and they’d be on their guard with you and make you damn well pay for it. But not Marion. She knew what I was and she thought that was okay. She saw through all my aggression to my pain and my trouble and she cared enough that I finally got around to questioning my own motivations. And I saw it all around me with other kids, again and again. She had a way of twigging onto people with low self-esteem and building them up, making them feel worthy; that something was going to be expected of them. And that was the thing. She wasn’t there to cram your head with her knowledge. She wanted to hear from you. A lot of people had never heard the word ‘reality’ before they had her. Some of them even got sick of the word. But that’s what she was saying: reality is a subjective evaluation that each of us has to come to and she wasn’t going to give you hers; she wanted to draw out yours. It was like a flowering. She helped focus things in me that I might never have gotten around to without her help. She certainly called them out earlier. It was such an intense time. You don’t forget a teacher like that.” Strange to say, Marion almost never taught at South, almost never taught again at all. England had been a revelation for her. In England she finally got to see the culture and the country; the human product born of all that literature she’d been studying all her life. No longer a remote and intellectual exercise, she realized that there was a life to be lived at the heart of all this and that to stop at literature would be no life at all. When her stint at the English school was up, she donned a knapsack and went traipsing through Europe for three months, sleeping at hostels along the way and not returning to Canada until the fall of 1952. She had no intention of ever teaching again. Back at the parsonage, Marion hid herself away in her bedroom and started the task of writing up her last year’s experiences. Her mother had other ideas however. “I didn’t educate you for nothing, my girl. You’re going to work.” To placate her mother, Marion decided to make the rounds of London schools and fill out applications, confident that a job would never be less likely to appear than in October of a new school term. She went to Medway first – nothing doing – and then to Beck – nothing doing – and then as she wandered into the administrative office of South, she could hear the then-principal, C.M. McCallum, talking on the phone to the Board, telling them that what he needed right away was a teacher of English and Latin. Her fate had just sealed itself right before her eyes. The principal hung up the phone and Marion stepped forward to introduce herself. “Hello, Mr. McCallum, I believe I’m the person you’re looking for.” FOR HER FIRST SIX YEARS at South, Marion was known as Miss Boa. Then in 1958 she became Mrs. Woodman. Born in Port William, Nova Scotia and raised in Winnipeg, Ross Woodman was a professor of English at Western, (specializing in the Romantics) and an influential art patron and widely regarded critic whose musings did much to bring coherence and attention to at least two generations of London artists. They had first met when Marion was helping Ross as a teaching assistant. “We had a wonderful time,” Ross told me. “But I knew there was quite a fundamental difference between us. I said, ‘You know, Marion, your first and primary interest is not literature, it’s the students. You look at literature in terms of soul-making. And my attitude is a much more academic one.’ I was interested in literature as an end in itself. I came to see that our two patterns were complementary rather than antagonistic.” Indeed, Ross would identify the “hidden dynamic” of their marriage as “the coming to the feminine through the masculine and the coming to the masculine through the feminine.” Marion needed Ross to help her cultivate incisiveness and discrimination. Ross needed Marion to bring him out of a too compartmentalized, too abstracted world view. Both Woodmans had an uncanny ability to draw out even the shyest and most alienated of their students and awaken them to their own deepest mysteries and potentialities. It wasn’t an approach that every student appreciated but for those whose antennae could pick up the Woodmans’ signals, they were major, life-shaping teachers.  Fraser Boa. Photo by Chris Aikenhead Fraser Boa. Photo by Chris Aikenhead By the time I showed up at South as a lowly grade-niner in September of 1966, Fraser had joined his sister in the English department and – though I had neither of them as a teacher that year – was the first of the siblings to register on my consciousness. The London Little Theatre company brought its dress rehearsal of The Music Man – opening later in the week as the first production of the season at the Grand Theatre – to our school auditorium. Even if I didn’t enjoy it much – I’ve never been a big fan of musical theatre – I hated to see it end as it wiped out the first three periods of the day and significantly shortened those that remained. Fraser had the title role of con man Harold Hill who couldn’t read a note of music but routinely sold small town councils on the improving aspect of band music for their young people. Pocketing all the money for instruments and lessons that would never materialize, Hill would then move on to the next unsuspecting town. It would take me a few years to begin to appreciate just what an appropriate role that was. No, Fraser Boa was not a con man but, like Harold Hill, Fraser had energy, charm and confidence in abundance and when he set about ‘working a room’ or pushing a scheme, he was well-nigh irresistible. That customary smidgen of academic diligence that had allowed me to coast through elementary school without ever doing much work, wasn’t enough anymore and I surprised myself by flunking grade nine. Not caring much either way, I was persuaded that perhaps I’d fare better in a four-year business and commerce course at H.B. Beal. I scraped through my repeated grade nine there (I’m not sure it would have been possible for anyone to fail anything at that school) and then, fed up with the pointlessness of a business-based curriculum, quit school altogether in the winter of my grade ten year. Hiding out in my parents’ basement over the next six months, I reverted to a night owl’s schedule and started to do a lot of writing. Even though it was pretty unremarkable, adolescent stuff (poems about prostitutes I didn’t have the nerve to visit; that sort of thing) I luckily didn’t know that at the time. Encouraged to the point of intoxication by the results, I decided to take another run at the arts program at South and see if I found school a little more congenial now that I had fastened onto a skill that I was actually interested in developing. MARION WAS AWAY on her latest sabbatical when I turned up there in the fall of ’69 for my second run at grade ten. My English teacher that year was Marion’s replacement and Darla Campbell was just what the doctor ordered; a beautiful young rookie with a generous heart who encouraged me like nobody’s business. But even aside from the bliss of that one class, I could see that the whole atmosphere at South had radically shifted in the two years I’d been away, largely under the influence of Marion and Fraser who had worked with English department head Tom Crerar and principal Bob Mann to introduce a two-year theatre arts course and oversaw the creation of ‘The Tostal’ on the second floor – a more intimate, flexible theatre space which was made by demolishing one wall between two classrooms and outfitting the new and larger space with broadloom, risers, track lighting and sound equipment. (As I recall, we were told ‘Tostal’ was a Welsh term for ‘meeting place’.) Fraser had recently started experimenting with film, took a couple of courses at UCLA and made some short art films. One of these called Chambers was created in collaboration with London artist Jack Chambers and hasn’t been seen in decades. The film provoked outrage and was quickly suppressed by Chambers’ wife, Olga, because of the inclusion of a sequence in which the death-obsessed artist drowned small birds which had been trapped in a net thrown over a fruit tree. Even in that Hall-Dennis era heyday of expanded programming and funding, it still wasn’t easy to sell the Board on Fraser’s next plan for overhauling one more classroom and a small office on South’s third floor – but he did it. In 1970 South became the first high school in Canada to have its very own 16-mm film department and a two-year course in film arts where students were kitted out with cameras, projectors, editing tables and splicing machines; all of it provided by the hapless London taxpayer. Movies got made and lives were changed. I can name at least four South vets (including a certain Chris Aikenhead) who have had long careers in film, TV or photography and every one of them would acknowledge that it was Fraser Boa who aimed them in that direction. By my grade 11 year, Marion was still away but I signed on for both theatre and (largely at the recommendation of Chris A.) film with Fraser. Fraser had little patience with students who only took one of his courses because they thought it was a ‘bird’ or they were just looking to earn points for diploma programs. In taking film, I learned a lot about the mechanics of film and gleaned a deeper appreciation for watching or appraising any sort of movie but as my own film never got finished (it was a sort of precursor to my 1988 play, Suffering Fools), you might conclude that the main lesson I learned was that film was not the medium for me. And while that is undoubtedly true, the real reason that film didn’t get made was because I was a little preoccupied with falling in love with Kirtley Jarvis in the only class we ever took together. That was the second year in film for her and - let the record show - she didn’t finish her film either. Indeed, we were so magnificently distracted that neither one of us got a lick of work done all year. MY EXPERIENCE OF THEATRE went much deeper. Now here was something I could hurl myself into. And the magnificent thing about Fraser was that no matter how bold and reckless that hurling became, he was always ready for more. The most fun I’ve ever had as an actor was playing a roaring and conniving Patiomkin in an in-class production of George Bernard Shaw’s The Great Catherine that Fraser directed. With an even halfway willing student, Fraser had a magical ability to infuse his performers with courage and an appetite for risk. He never stepped into some improvisation to say, “I think this has gone far enough.” But he could be lacerating if he thought you were holding back. I remember one girl who ran crying from the room after he called a halt to some half-hearted lampoon of motherhood that was clearly going nowhere. She said she loved her mother and was uncomfortable doing that sort of material. “Then why the hell didn’t you take algebra instead?” he barked and she was out the door in a flood of tears. He demanded a lot and could be brutally frank if he thought you were wasting his time. He cultivated a lot of friendships over his 59 years but wielding incisiveness as sharp as that, he also managed to make a full share of enemies. In that spring of 1971, Fraser was also directing that year’s big show in the main auditorium; another glitzy musical, Anything Goes. He persuaded me to take on the role of a pompous clergyman who only appeared in the very first embarkation scene until a scheming hood slyly usurps his place on board a transatlantic liner. No other student wanted such a piddly role but piddly was just fine with me, though I wasn’t too thrilled to discover that I’d then have to lurk about backstage, in full costume and makeup, for the better part of three hours, waiting to go on for the final curtain call; a stretch of empty time that became considerably less onerous when I started taking along an early novel and short story collection by Kurt Vonnegut Jr. (God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater and Welcome to the Monkey House) who Kirtley had put me onto. In the fall of 1971, Marion returned from her latest sabbatical and in her final three years at South she produced and directed three original shows which were entitled Any Fresh Egg?, Apocalypse and Affectionately, Eva. A blend of song and dance, prose and poetry from classic writers and from the students themselves, these shows stand almost as artistic blueprints of what Carl Jung calls the individuation process. The first show concerned the journey of the individual from innocence to experience and wisdom. The second traced a more metaphysical or spiritual trajectory from Creation to Apocalypse. And the third was a study of the evolving role of the feminine. Eschewing the main floor auditorium, Marion chose to present these shows in the Tostal. Because of its limited seating capacity, it was necessary to give each show a longer run to accommodate the crowds. Asked why she insisted on the Tostal, Marion said, “I knew if I put those shows downstairs, the kids were going to take all that beautiful material and work so hard at sending it out to the back of the hall, that they wouldn’t experience it for themselves first.” Though I’d officially dropped out again by the time of Marion’s return, in the 71–72 year I monitored a grade 12 English class and also took Marion’s personally designed Philosophical English course which included study units on such meaty fare as The Book of Job and Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot. I also helped out with script development, contributed a few poems and a dramatic sketch, as well as playing a couple of bit parts in two of those shows. The first two.  Marion & Herman, 1973. Photo by Neil Pfaff Marion & Herman, 1973. Photo by Neil Pfaff What Marion wanted, and what she got, were tuning forks; not trumpets. Even in actual performances you didn’t just go out there and belt your lines. You took your place on stage, you drew into yourself and you waited until the poem or whatever it was you were reciting moved up and through you. “The show can wait,” she used to say. “There’s no hurry. You begin when you’re ready to begin and the rest of us will just eavesdrop.” Of course, we weren’t allowed to mumble or slur our words but Marion was definitely after a sincerity that couldn’t be faked. Have you ever watched a sixteen year-old who’s really inside a poem by Eliot or a segment of Beckett? It can be a little unsettling. I remember standing just offstage one night while somebody else was on and looking out at some of the parents who’d come to see the show and wondering just what they made of it all; how they liked seeing their little Johnny or Jenny thrashing about on stage like their skin was on fire and raving on about being “stuck in rat’s alley where the dead men lost their bones” and cowering because they hear “the wind under the door”. Marion was introducing their children to some pretty powerful material, showing them rooms an awfully long way down the hall from the nursery. The parents didn’t all just love her style of pedagogy and long after graduation I would occasionally bump into colleagues from those shows or her classes who held grudges for the never-satisfied longings and quests, the never-resolved mysteries and never-answered questions that Marion had aroused in their hearts. I heard that when Fraser directed a production of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie at the Grand, he commented that the title character’s knack for instilling some of her students with ill-fitting dreams that might just turn around to bite them, reminded him of Marion at her most exuberantly reckless. Having flunked and quit school twice, I was that little bit older than her other students and I was already focused on writing as the thing I was called to do. I loved and admired Marion but having already harboured a Platonic passion for Darla Campbell, I was never susceptible to become one of Marion’s acolytes. Marion and I drove down to Woodstock once to pick up a prop we were using in one of her shows. It was a large wooden box with a removable lid that I’d made back at Beal in Industrial Arts; originally conceived as a coffin for the family dog who died a little too soon so I refashioned it as a brutalist coffee table and had given it to a friend. Marion called when I was out to make arrangements for the pickup and my Dad answered. It was his only encounter with her in his entire life. He’d talked to her for maybe two minutes and – evincing his intuitive powers which could sometimes be alarmingly sharp – left a message for me that read: “Herman, call the Enchantress.” Equally uncanny, I knew exactly who he meant. I FIRST MET ROSS FACE TO FACE in the winter of 1971 – 72 when a group of bohemian keeners who’d been involved in Marion’s latest show decided to hold a dinner party for their favourite teacher and that utterly unknown quantity, her husband. Ross completely stole the show. Our host’s parents were away in Florida so we had the house to ourselves. In the evening’s very set up – eight or so teenagers putting on a precociously grown-up dinner party – there was already a sense that we were perched on the brink of a new and more adult phase of our lives. And this Ross graciously and generously confirmed by going around to each young member of that party in turn and deftly drawing them out, getting them to talk about their dreams and aspirations and making them feel understood and affirmed in a way they had never known before. I remember that we were all so engrossed in the conversation that nobody could tear themselves away from the table for long enough to change the bloody record on the turntable; side two of Joni Mitchell’s Blue playing over and over again.  Herman & Ross, 2008. Photo by Kirtley Jarvis Herman & Ross, 2008. Photo by Kirtley Jarvis It was the same sort of gift for awakening and inspiring that Marion and Fraser wielded; an intuitive ability to take a quick read of a young person’s proclivities and the situation they currently found themselves in and imagine how they might be more fruitfully conformed. Ross seems to have developed this gift by employing it on himself. I was shocked when I first heard about his utterly uncultured childhood in a splintered, feuding Winnipeg family which he would routinely escape by going to the movies alone and immersing himself in an infinitely more stimulating world. And it was his love for the movies that led him to his professorship. Mooching around in the library one day, he was flabbergasted to discover that Alistair Cooke had edited a collection of essays on film entitled Garbo and The Night Watchmen. He reckoned that he checked that book out a dozen times; excited out of his tree at the idea that movies or any other kind of art weren’t just pleasant diversions but when properly rendered and intelligently received, could wrest meaning and purpose out of any kind of life and point us toward the divine. With the development of international used book sellers with enormous inventories like Alibris and ABE Books in the early days of the internet, one could suddenly procure books you’d been searching for all your life and I was able to give Ross his very own copy of Cooke’s book which he unwrapped and stared at as if I’d just dropped the Holy Grail into his lap. What I particularly treasured in Ross was his pronounced literary acumen (his knack for putting his finger on the weakest element of any narrative was unfailing) and the tips he could pass on about making my way in the publishing world. A couple years after that introductory dinner, he gave me some very worthwhile advice after I’d elected to go to jail for two days for the crime of cycling through a red light at four o’clock in the morning. Following my release I’d furiously written up a 30 page account of my experience; a diatribe so angry and raw and unhinged and . . . long . . . that it took me almost 15 years to knock it into any sort of publishable shape and find a home for it. When it did finally get published, I was chuffed to hear from London lawyer, Ted McGrath (now a judge) that he found my account invaluable when he was throwing together his 1990 novel, Donnelly’s London, parts of which were set in the old London jail. After writing that first draft of My Life of Crime, I was more than a little strung out and ran several more red lights cycling over to UWO campus where I dropped in on Ross. He’d just finished teaching a class and we repaired to his cramped little office. This was my only encounter with Ross in academic situ and the place seemed an inadequate context for the man; like consulting with a wizard in a cubicle. But then there were many aspects of Ross’ life that I struggled to fit with the man I’d come to know. This most sensitive of human reeds who could quiver with the beauty of a poem or a canvas, had served as an RCAF tail gunner in World War II. Once he told me he waved to the enemy airman whose plane he’d just disabled and received a stern reciprocal salute as the poor pilot went plummeting to his death. This was hard to put together with Ross' ineptness for all things mechanical. Another time he parted the veil a discombobulating smidgen regarding his mysterious first wife and the mother of his two children, telling me about their summer hauling a trailer as they followed Eddy Arnold from concert to concert. Filmmaker Chris Lowry who's been diligently researching Ross' life for several years now, cautions that a measure of skepticism should probably be applied to some of his more outlandish and incongruous claims about his early life. My own suspicion is that while such tales may not have been entirely accurate, they probably weren't utterly baseless either; that they came from somewhere and Ross had his own inspirations for telling them; that whatever some recollections may have lacked in strict veracity doesn't alter the irrefutable fact that the man contained mind-wrenching multitudes. So there we were in his university office. Ross read my screed, laughing in a few spots and sighing in others, then took a minute to gather his thoughts before pronouncing judgement. He told me that the piece could not be published as it was; that no one would touch it, nor should they. The whole thing was irresponsible and intemperate but there were insights there, hard won and quite powerful, that I would be able to draw on for the rest of my writing life. But his major advice was that I shouldn’t try to fix it up right then or anytime soon. “Put it aside,” he said. “Get some distance from it. You won’t be able to but I urge you to forget about it. The danger I perceive is that you are identifying with this experience so strongly that you might get stuck here and that would be a horribly limiting waste of your talent.” It was time to discover or devise an off switch and head off to till a completely different field more likely to produce a yield. And I did. I’ve had occasion to use that switch many times over the intervening years when I find I’m getting way too preoccupied with a certain problem and am allowing it to dominate my life to the point of detriment. It’s one of the greatest gifts Ross ever gave me and I often wish I could share that sanity-saving switch with some of my more stressed-out friends who don’t seem to have one. The hallowing of pain, Like hallowing of heaven, Obtains at corporeal cost. The summit is not given To him who strives severe At bottom of the hill, But he who has achieved the top. All is the price of all. – Emily Dickinson OUR TRIO OF BOAS AND WOODMANS did indeed have a propensity for challenging their students to take the miraculous opportunity of their lifetime seriously; to dream big and risk all in pursuit of self-actualization. But it wasn’t something they just postulated for others. By the time of Marion’s retirement party, she and Fraser had both cast any semblance of security to the winds and were radically overhauling themselves from top to bottom. The first one to leap off the ledge was Fraser. At the age of 39 he was entering into a midlife crisis that made most other men’s crises look like passing bad moods. He looked at everything he’d accomplished and was involved in, and said he felt like a man who’s been so busy climbing each rung of the ladder that he’d neglected to notice that he had propped his ladder against the wrong wall. “Simply put, my whole existence suddenly added up to a loud, ‘So what?’” he said. Fraser quit teaching and, leaving his wife and kids in their family home in London, he worked with a partner in re-opening an old foreign film house on Roncesvalles in Toronto as The Revue Cinema – one of Hogtown’s first repertory cinemas. A number of his ex-students from South picked up jobs as ushers, ticket-sellers, cleaners and all-round cinema dogsbodies. That business had only been operating a year when he was knocked flat by a heart attack. Perhaps this was life’s way of saying, “You’re not getting off that easily, Boa – look a little deeper, why don’t you?” On her last teaching sabbatical, Marion had undergone her analysis in England, and she suggested to her brother that as long as his life was in tatters anyway, he might as well give that a try. So taking the family with him this time, Fraser went overseas, first for analysis with Dr. E.A. Bennett in London (earning money by working on the Albert Finney version of Murder on the Orient Express through his connection with that film’s co-producer, Richard Goodwin) and then for his own analytical training in Zurich. Jungian analysis is entirely dream-based and dream-driven. It’s a form of psychoanalysis which is not to everyone’s taste but for these children of the parsonage who grew up in a world infused with symbols and rituals and who had committed their professional lives to the exploration and presentation of all kinds of narrative and poetic drama, dream analysis seemed tailor-made. I once interviewed Marion about her training as an analyst; a similar regimen was doubtless required for Fraser. For four and a half years Marion rented a room in a private home in Zurich, Switzerland and attended twelve hours a week of lectures and seminars, did 40 hours a week of control work (35 of those hours in session with her patients and five hours with analysts who oversaw her work) and spent another twenty to twenty-five hours a week working on her own analysis. “All is the price of all” had become the ruling motto of her life. It was a point of honour for Marion that she paid the crippling prices for everything in Zurich with her own money earned as a teacher. TO BE ACCREDITED AS AN ANALYST it was necessary to write a major thesis, to pass two sets of eight exams and to receive the nod of approval from a selection committee that conducts interviews with each candidate to ensure that they can both empathize with others but also stand apart and not succumb to the myriad of subtle, psychological threats which an analyst must face every day of his working life. If that sounds a little hokey to you, then just take a look at the alarming rate of suicides in the psychiatric professions. In addition to a deep understanding of life, dreams, religion and myth, an analyst requires a two-fisted grip on his own psyche before he can go mucking about in the psyches of others. Anything less would be reckless irresponsibility in a most fragile and sacred realm. “I think that twenty-two years of teaching English literature prepared me for this job,” Marion told me in 1982. “Any great piece of literature is working with symbols and relating to the whole world of symbolic imagery. And dreams are poems. In helping a person understand their dream, you help them understand their own poetry; their intellectual, emotional and imaginative response to their own world.” Marion’s extended furlough in Zurich put a definite strain on her marriage. I remember dropping in on Ross one muggy summer evening during a rather rough patch. Their house up near the university was dark but during those half-attended years with Ross shuffling around on his own (he pretty well took to his bed in a state of morbid engrossment for the entire summer of the Watergate hearings) darkness didn’t necessarily signify absence. Eventually he answered the door in his bathrobe, blinking a little at the streetlight’s glow, and invited me into the living room, casually adding, “Now, watch you don’t step on Marion.” Indeed, Marion was home on a flying visit from Zurich and as her back was giving her grief, she was stretched out on the floor, simultaneously trying to realign both her lumbar vertebra and her marriage as she and Ross talked in the dark. Clearly it was a bad time to come calling and I took my leave just as soon as I graciously could; fearing during my walk back home that this union of two such wonderful souls really might be knackered. But they came through and grew from that period of trial. FRASER SET UP SHOP AS AN ANALYST in Toronto in 1977 and two years later I entered into analysis with him, commuting two days a week on the ‘VIA psycho express’ for 18 months, earning my train fare most days by scooping up twenty LP's from my collection to sell to City Lights Bookshop on my walk to the train station. I was dirt poor at the time and Fraser gave me a very generous break in his fee (which might surprise those who only knew his ‘Harold Hill’ side). I was driven into analysis pretty much against my will, once my wife of one and a half years (and on-again, off-again main squeeze and all-round obsession ever since we’d met in film class in the fall of 1970) had started into analysis with Marion who had just begun practicing in London. Kirtley and I had sustained at least four major breakups before getting married and had deduced that because we always seemed to find our way back to each other as the only person who really made sense in this world, perhaps we should try sealing the union with some civil cement that would make it harder to burst apart again. Well, now we were testing the holding power of that cement. Kirtley had no sooner entered analysis than she became incomprehensible to me which was more than a little terrifying. When a person starts into a program of intensive dream analysis, their vocabulary and terms of reference and all of their personal priorities dramatically shift. They start scrutinizing everything they do and are forever drawing apart to scribble in their journal and no longer have the time or inclination to sit around killing a bottle of vermouth and talking about your relationship until you sort of fix things up enough to hobble along for another few weeks. The sudden change in the tone and routine of your life together is totally bewildering and threatening to the spouse who isn’t similarly immersed in Jung-think. I had no illusions that our young marriage was in robustly fabulous shape but I frankly hated the idea of having any sort of professional peering into and passing judgements on the dynamics of our relationship. We’d had a few sessions with a publicly funded counsellor whose pedantic ministrations barely scratched the surface of the mess we’d so quickly worked our way into and I was more convinced than ever that if we were going to find a way to set this thing right – and there was nothing on Earth that I wanted more – we would do it on our own. What I didn’t yet appreciate was that in properly overseen dream analysis, you are working it out for yourselves. All the messages and directions that are being received and acted upon are coming from within; from that part of you that knows more than you consciously know and plays six or seven private movies every night that you haven’t been paying any attention to. After my ever more disconcerting stranger of a wife had racked up two or three sessions, I impulsively headed over to see Marion unannounced. I was in a bit of a panic but at least had the wits when she answered the door to say, “Look, I know this breaks every rule in the book and I’m not trying to get you to betray any confidences. But I’m flapping in the breeze something awful here. Is there anything you can tell me or suggest to help me affix some kind of handle to whatever’s going on?” MARION RECOGNIZED THE PICKLE I was in and was able to generally explain some of the principles in play in Jungian analysis but reiterated what I already knew from Kirtley; not only could she not reveal anything being discussed in their sessions, she would not be able to offer me any counselling herself. In Ghostbusters parlance, that would ‘cross the streams’ with potentially disastrous results. Marion was in Kirtley’s corner, helping her map out her own psychic topography; a delicate process that might become skewed if she had to simultaneously concern herself with mapping out mine as well. The implication of this was as I’d feared: there was no guarantee that our marriage would survive the ordeal of analysis. And the other main upshot of my visit with Marion was the realization that anything like stasis (my preferred state in my depressed condition at that time) was no longer an option. Kirtley’s train had already left the station and if I ever hoped to resume the dance of life with the woman I loved then – ready or not, like it or not – I was going to have to get a ticket on my very own train and head on in to the unexplored country situated between my very own ears. It was time to get a shrink of my own and at that particular moment in history, there wasn’t another Jungian therapist taking on patients in London so I got Fraser which – deliciously enough – made Kirtley jealous. In retrospect, I think her lack of indifference on this matter was my first hint that maybe we'd come through this intact. Kirtley adored Fraser from film class days and had never had much to do with Marion. I liked him a lot but if you’d asked me which of these siblings I would be more comfortable trusting with my innermost secrets, it would’ve been Marion at that time. But Fraser was the one that I needed. I didn't recognize yet how starved I was for specifically masculine insight. My relationship with my Dad had been plugged up for years and was stunting my growth. I bore such a silent grudge against him that it was preventing me from becoming an adult male myself – it would make me too much like him – and taking full responsibility for my life. I was writing next to nothing after a local publisher went bankrupt and left town without releasing me from a book contract, making my second novel, into which I had poured about three years’ work, legally unpublishable. “Yeh, that’s tough shit, all right,” Fraser told me. “Now what are you going to do about it?” What? He wasn’t going to commiserate with my misfortune? He didn’t think one setback was reason enough to shelve all artistic ambition? That this catastrophe was all the evidence a sensitive person needed to deduce that the world was unfair and there was really no point in trying to set things right? And what changes was he working on me already that I found this apparent heartlessness of his kind of inspiring? In recent months watching the Jung-influenced University of Toronto psychology professor Jordan Peterson encourage thousands of people – but particularly young men – to shake off the soul-shrinking incriminations projected onto them by society at large and get in touch with their own best and deepest ambitions for improving their lives, I’ve been reminded again and again of the primary dynamic at work in my analysis with Fraser. To my certain knowledge, I’ve only ever committed one spit-take in my entire life and that was in Fraser’s office during my third or fourth visit when he said he’d like to see me earn $50,000 that year and blooey – I drenched my dream journal and his table with spewed coffee. As a teacher, theatre director or analyst, that – for me at least – was Fraser’s greatest gift. He took a reading of your dreams and your potentialities and postulated this daunting and infinitely desirable goal and said, “That’s what you need to be shooting for.” That was his way of leading you out of your cave of timidity and self-doubt. He dared you to go further than you’d ever gone before and you did. No, I never did pull down fifty G’s a year but it was Fraser who got me writing for a living, who urged me to quit every job that wasn’t writing even when it meant I’d be paying him peanuts for analysis. “But it’s impossible, Fraser. Nobody makes a living from just writing.” “That’s right. So let’s see you do it.” As it turned out, Marion’s office in London was an early experiment she soon abandoned, finding that her past familiarity with the town acted as an impediment to the ideal analytical relationship in which both parties have to be so committed to the task at hand that complete and sometimes ruthless honesty becomes possible. Within a few months Marion moved into another office in the same suite of rooms as Fraser, finding that her relative anonymity in Toronto made such relationships easier to establish and the larger population supplied her, almost instantly, with a full appointment book. It also meant that Kirtley and I could travel down to Toronto together on the psycho express, making sure we got seats with a table for the return trip so that we could open up our journals and write up our accounts of that day’s sessions. WE KEPT UP OUR ANALYSIS until the summer of 1980 when Kirtley became pregnant with our first child. It was an unlikely sort of set up for sure; a husband and wife who used to be students being analyzed by a brother and sister who used to be their teachers. It was such an exciting period of discovery and growth in our lives and we always felt doubly blessed to be going through this in our 20s. The last thing we’d see each day as we left their offices was the invariably middle-aged or older clients who were waiting to go in next and I couldn’t help feeling a – probably misplaced as I knew nothing about their circumstances – pang of sympathy for them. How awful to make it into your 40s or 50s before realizing that you’d aligned your life all wrong. Better late than never, I suppose, but surely the time to be playing Fifty-Two Pickup with every aspect of your existence is when you still have energy to burn and you haven’t taken on so many personal and professional commitments. Even at the time I recognized that there were aspects of our immersion in analysis that had decidedly cultic overtones. There was the sudden transformation of – if not the personality – then certainly the priorities of the patient or ‘analysand’ as they called us. There was the rapid adoption of a new vocabulary – ‘conscious’ and ‘unconscious’, ‘anima’ and ‘animus’, ‘archetype’, ‘individuation’, ‘projection’, ‘synchronicity’, etc. Many of these words denoted concepts that could have been invoked using already familiar terms and the fact that they didn’t, aroused my suspicion a little in a Scientology-ish way. The plain-spoken Greg Curnoe mocked ‘synchronicity’ as pretentious gobbledegook for ‘coincidence’; a clear-eyed distinction that made me admire him all the more. As analysis was unquestionably doing me a lot of good, I often felt (and, I hope, usually suppressed) the impulse to convert others to the cause. But at least as often, I would find myself in the presence of friends and acquaintances who were so clearly functioning perfectly well without recourse to any such elaborate psychological system that I couldn’t help thinking, “Good for you”. I don’t pretend that I ever attained the status of a Jungian adept or even wanted to. I never had any intention of taking it on for life. The unexamined life may not be worth living but, by my lights at least, neither is the over-examined life. Analysis can be wonderfully effective if you need to blow up some great paralyzing roadblocks that keep you from honestly grappling with the issues that matter most. But once those big breakthroughs have been made and it’s time to get on with conducting a day to day life – holding down a job, raising some kids, doing something more constructive with your time than morbidly scrutinizing every impulse and inner twitch (“I’m apparently breathing in . . . I’m apparently breathing out . . .”) – then analysis can actually become a little enervating. Once I knew who my wife was, had forgiven my father and had once again taken up the work I was put on this earth to do, my feelings about the whole process could be best summarized as, “Thank you very much for all your help. But I think I’d prefer to take it from here.” Perhaps most unexpectedly for me, analysis also turned out to be my gateway to Catholicism. Even before my last session with Fraser, I knew there was still one more enormously important decision that I’d been putting off for too long: What about God? One bonus of visiting Fraser twice a week in Toronto was getting to slip into some of the formidably well-stocked second-hand book shops in that town before or after our session. Except for Man and His Symbols, Modern Man in Search of a Soul, and his autobiography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, I found Carl Jung a gnarly and uncongenial writer. But 'Religion' was routinely situated a bookcase or two away from any shop’s 'Psychology' section, and there I was acquainting myself with a whole raft of authors who spoke much more directly to my soul. I’ve always said it was having kids to whom I would always be answerable about what really matters in life that forced my hand in coming to terms with faith in Jesus Christ. But analysis also played a major part in preparing me to take that plunge. How so? Well, let’s just say that undertaking eighteen months of intensive work interpreting unconscious stories of sublime instruction that came whiffling into my sleeping brain every night from . . . where exactly? . . opened me up to a wider range of cosmic possibilities in the universe. THOUGH IT TOOK ME three more years to make my way into the Church, late in our analysis I told Fraser the direction in which my fascination was inclining and he didn’t poo-poo it. To dismiss it out of hand would’ve been un-Jungian. But I also knew that Fraser wasn’t equipped to act as my Virgil for the next leg of my metaphysical trek. Unlike Freud, Jung never made the mistake of dismissing religion as an empty illusion or a manifestation of neurosis; he just didn’t think it worked very effectively in our own less credulous and more sophisticated age when so many churches seemed to be running out of gas. While they retain a qualified respect and admiration for the archetypal pertinence of classical Christianity, Jungians don’t see Christian faith as a realistic or responsive option for modern man. The crux of the matter seems to be whether you believe those uncanny parables that unfold in your sleep every night – otherworldly yet astonishingly conformed to the particularities of the life you’re living in this world - ultimately come from within or without. Are they entirely self-generated phenomena or are they the fruit of some larger, external and overarching truth which has been planted in each human heart? If they solely come from within, then the whole Christian edifice is a massive projection that serves as a sort of prophylactic; immuring people from having to manage their own psychological individuation by casting the whole process onto that vicarious scapegoat called Jesus. And if the healing instruction of dreams ultimately comes from without – and the entire pantheon of Jungian archetypes and symbolism is actually a desacralized substitution for the divine drama which can only bestow its ministrations when it is consciously acknowledged and gratefully received – then man really is a fallen creature who will never bring lasting order to his contending drives and impulses until he submits to his Creator. In Psychology and Alchemy, Carl Jung makes the case for ‘within’: “In so far as the archetypal content of the Christian drama was able to give satisfying expression to the uneasy and clamorous unconscious of the many, the consensus omnium raised this drama to a universally binding truth – not of course by an act of judgement, but by the irrational fact of possession, which is far more effective. Thus Jesus became the tutelary image or amulet against the archetypal powers that threatened to possess everyone. The glad tidings announced: ‘It has happened, but it will not happen to you inasmuch as you believe in Jesus Christ, the Son of God!’ Yet it could and it can and it will happen to everyone in whom the Christian dominant has decayed. For this reason there have always been people who, not satisfied with the dominants of conscious life, set forth – under cover and by devious paths, to their destruction or salvation – to seek direct experience of the eternal roots, and, following the lure of the restless unconscious psyche, find themselves in the wilderness where, like Jesus, they come up against the son of darkness.” And here, at one seventh the verbiage, is Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger in his Introduction to Christianity, making the case for ‘without’: “Meaning that is self-made is in the last analysis no meaning. Meaning, that is, the ground on which our existence as a totality can stand and live, cannot be made but only received.” Perhaps it all boils down to temperament. Perhaps I really am a rather simple and literal-minded chap and an instinctive proponent of what Christopher Aikenhead identified as his ‘pet peeve’ in our high school yearbook: “(externality)”. (How foxy of him to tuck that particular word inside brackets.) Not only do I find the language of the Church infinitely more compelling and accessible than Jungian jargon, the architecture and the art and the music and the poetry and the stories she inspires are the finest and the richest that mankind has ever created. The Catholic Church doesn’t just have cultic overtones; it is the grandest mother of all soul-cultivating and culture-inspiring cults that ever there was and is and ever shall be. And with regular confession demanding the same sort of close self-scrutiny as analysis – and a per-hour pew rental that comes in at a fraction of the cost of renting any analyst’s couch except Fraser’s – this is a form of analysis I can happily and proudly submit to for the rest of my life. Interestingly enough, in a 1954 collection of essays about Catholic conversion by various hands called The Road to Damascus, Jung himself is quoted as acknowledging that Catholics do not seek out analysis with anything like the frequency of adherents to other faiths: "During the past thirty years, people from all the civilized countries of the earth have consulted me. I have treated many hundreds of patients, the larger number being Protestants, a smaller number Jews, and not more than five or six believing Catholics." WITH THE CONCLUSION of my analysis, Fraser and I ceased to see each other. Unlike my ongoing friendships with Marion and Ross, we never developed a relationship that wasn’t predicated on me being taught or directed or analyzed. Chris Aikenhead’s relationship with Fraser went much deeper and he worked with him through the 1980’s on a number of projects where Fraser was able to marry his interests in film and Jungian analysis. First Fraser produced, directed and hosted a series of ten one-hour interviews with Dr. Marie Louise von Franz (after Bennet’s death, the last of the original Jungians). In these shows von Franz analyzed the dreams of about fifty different people from Canada, the U.S., Europe and Britain. The dreamers were captured on film, telling their nocturnal tales and then von Franz interpreted each dream and answered supplementary questions posed by Fraser. The series played in major centres all over Europe and North America where top prices were charged for a sort of weekend package including hotel accommodation, all ten films and commentary from Fraser. The Way of the Dream, as the series was called, was also published in book form in 1988. He followed that up with This Business of the Gods, a shorter series of filmed interviews he did with the comparative mythology scholar Joseph Campbell in the last year of Campbell’s life. I’ve never seen this series and only read the accompanying book which he dedicated to Chris who served as sound man on the project. There’s a very appealing informality to Campbell in these chats that I think would have appealed to a large audience if they’d ever had the chance to see the series. Unfortunately, Fraser and his independent production company, Windrose, got utterly snookered by the near-simultaneous release of The Power of Myth, another (and far glitzier) Campbell interview series and book tie-in that was produced by the mighty Bill Moyers and was backed up by the combined muscle of the Public Broadcasting System and Random House publishers. While Fraser gave me a major break on my analysis fee, he did exact some supplementary payment by mooching an awful lot of cigarettes during our sessions and sometimes had me fetch him a fresh deck from a shop down the street before I caught my train back to London. And all those cigarettes caught up with him when he died of lung cancer at the age of 59 in March of 1992. At his funeral, ex-theatre student and United Church minister Steve Chambers read Dylan Thomas’ Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night, and, from all accounts Fraser Boa did not. Two weeks before his death he was making plans for more films and counting on the next round of chemotherapy to pull him through. There was so much more that he wanted to do but I suspect that would have been true of this driven and greatly daring man at any age. IN HER FIRST YEAR and a half as analyst, Marion went through the material she’d composed for her Zurich thesis and recast it as a book, The Owl Was a Baker’s Daughter, a study into the psychological causes of obesity and anorexia nervosa in women. This was followed by seven other titles Addiction to Perfection, The Pregnant Virgin, The Ravaged Bridegroom, Leaving My Father’s House, Conscious Femininity, Dancing in the Flames (which was dedicated to the goddess Sophia) and Coming Home to Myself; all of which explore different aspects of feminine – and what too often strikes me as stiltedly feminist - psychology, with lots of railing against the wickedness of the “patriarchy” whose “power structures have profoundly wounded” our understanding of the feminine and the masculine, and yadda, yadda, yadda. How well this bandwagon-hitching would’ve gone down with Carl Jung is an interesting question to ponder. In the 1990s, Marion started working with American poet Robert Bly who’d hit the big time with Iron John, a study of how mythology and poetry could help to address the uncertainty many modern men were feeling after a few decades of the feminist critique. In 1998 Marion and Bly produced The Maiden King: The Reunion of Masculine and Feminine, and in 1995 I was able to take in one day of their popular two day-long seminar/workshops out of which that book grew. Eleven years into my life as a Catholic by then, I was struck by how intangibly vague the conceptual transactions of one-on-one Jungian analysis became when generalized and refitted for a mass audience. During the lunch break I talked with a woman who revered Marion and had read all of her books but whose hold on sanity was so shaky that she had been turned down as a potential analysand. Though she was thrilled to be at this workshop, she knew she was having to make do with a very dim approximation of the kind of encounter she longed for and I couldn’t help feeling she was being ripped off.  Marion, 2012. Photo by Kirtley Jarvis Marion, 2012. Photo by Kirtley Jarvis Marion’s final book, Bone, published in 2000, is her least clinical and most personal and the book I would recommend to any reader not steeped in the Jungian mythos who wanted a sense of what she was like. Framed as a journal of her harrowing struggles with uterine cancer, her voice can be heard most distinctly here as she opens up and reflects on many aspects of her life and her marriage. It is far and away my favourite of her books and would be even if I didn’t get a mention late in the proceedings when she includes this diary entry from March 21, 1995: “To Herman and Kirtley’s for dinner with their three children. Memories of family sitting down to turkey dinner. I began to mention the many dinners I had cooked. Herman burst into laughter. ‘Marion, you don’t cook.’ And he believed it. He never associated me with a kitchen, cooking, cleaning. Few people do. We rarely entertain now. But time was when I served dinner (everything homemade) to forty to fifty people. The theatre closing night parties, the glorious Christmas parties with all the children in the pageant, the elegant dinners after I took the course in Old London at the Cordon Bleu. Ah, yesterday!” ABOUT TEN YEARS AGO the idea of both dispersing his art collection and solidifying his legacy was much on Ross’ mind. With an eye to publishing a book, Ross and I started to gather up the best of his critical essays about Canadian and London art from forty-some years’ worth of scattered newspapers and magazines and exhibition catalogues. I was going to write an introductory sketch of the great man himself for what we proposed to call A Ross Woodman Reader. Early on the folks at Museum London expressed an interest in our project and floated the idea of also hosting an exhibition comprised of work from the Woodmans’ private collection that would coincide with the publication of the book. At that point Ross didn’t have any relationship with Museum London to speak of and had already given a ton of his stuff (a lot of it London-based) to the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto where they had always had the good sense to woo him. If Museum London had played their cards at all well, they might have changed that situation but the one 90-minute meeting we had with their director and marketing head couldn’t have gone worse. Personally insensible of the semaphore and etiquette required in cultural deal-making, I didn’t realize how offensive he found their suggestion that he should substantially underwrite the book and the show himself. Indeed, everybody was smiling and nodding so much that I actually thought our meeting had gone fairly well until Ross and I were walking across the bridge back to our place and I witnessed this serene and unflappable man expressing a level of pig-biting rage such as I’d never dreamed he was capable. “That does it,” he said. “The AGO gets everything.” So the world still awaits the arrival of A Ross Woodman Reader. Of those that were published, his three most engaging books hail from the ‘60s and the ‘70s: an early appraisal of and interview with London artist Jack Chambers; a literary critique of the poetry of his UWO colleague James Reaney, and an exploration of The Apocalyptic Vision in the Poetry of Shelley. In the final decade of his life, Ross produced two final volumes – Sanity, Madness, Transformation: The Psyche in Romanticism, and Revelation and Knowledge: Romanticism and Religious Faith – which, as their multi-barreled titles portend, are so thick with academic and psychological lingo and so light on persuasive exposition, that I’m afraid I can’t make much headway with either one. For me, the great books were the earlier ones. Shortly after I’d scored a copy of his Shelley at City Lights Book Shop, I asked Ross to inscribe it for me, which he did on a November evening in 1982 as I was packing up my library to start moving next day into the house where we still live today. “What’s she done for me lately?” he asked, scratching out Marion’s name in the printed dedication with a chortling laugh and inserting mine in its place. Underneath, quoting Shelley’s Adonais, in which is suggested the liberty of the soul after all earthly bonds are loosed, he wrote: “Peace, peace, he is not dead, he doth not sleep – ”. I was sorry to miss Marion’s funeral. Boas and Woodmans know how to send off their loved ones with panache. I remember at Fraser’s there was a pianist playing Goodnight, My Someone, (which is a more tender setting of the same melody as Seventy-Six Trombones) reminding me of that first day I set eyes on Fraser playing that handsome operator with a gift for selling people dreams. At Ross’ funeral service as speaker after speaker stood up to talk or had their messages read out about his impact on their lives – whether it was a visual artist, a psychoanalyst, a professor, a carpenter, a filmmaker, a musician, a shopkeeper or one of his students – the import was the very same as what that group of callow kids had experienced at that dinner party 40-some years earlier: this wonderful man understood me in a way that helped me so much and gave new direction to my life. BUT IF I MISSED HER FUNERAL, I like to think I had a sort of preview glimpse of Marion’s possible afterlife. It was a muggy day about five or six summers ago. Kirtley and I were over at Ross and Marion’s art-plastered condo with son Hugh and were helping Ross lug nearly all of his library up to the recently vacated apartment on the floor above which Ross had impulsively bought as well. Marion was pretty ditzy by then and had finally been persuaded to pack up her practice and stop giving seminars as her memory and grip on reality became increasingly unreliable. I think Ross mainly wanted this extra space so he’d have somewhere quiet to go and read when the caretakers dropped by to look after her for a few hours. Hauling crates of books from their oh-so-familiar apartment into what felt like an adjoining secret annex, was redolent of those marvelous dreams you sometimes have where you open a door you've never noticed before and discover a whole new wing in your house. I'd had one something like that the night before I entered into analysis with Fraser. My new space in that dream was outfitted with an elevator to transport me between floors; an apt representation of the process I’d signed up for. After three full walls of bookshelves were newly stocked, we all sat down in the nook of a top floor gable window and drank some tea. Ross and Marion told a wonderful story about a rather dramatic stay in England when their relationship was going through one of its more tumultuous patches and Marion had somehow managed to set one of her dresses on fire while ironing it. With older material like that – and with Ross at her side to keep her anchored - she wasn’t so inclined to drift off into the ether. It was more contemporary events that could really throw her for a loop. And now, suddenly glancing around in an uncertain way, she broke off the conversation to take hold of Ross’s arm with some urgency. “Ross,” she said, “I don't think we're supposed to be here. Those people might come back. We shouldn't be here like this, should we?” “It’s perfectly all right,” he told her. “We live here now too.” “Do we, Ross? Really?” “Yes, Marion, we do.” And then she sat back and relaxed once again in acceptance of this expanded reality. “We are so lucky to have all this, aren’t we?”

3 Comments

Susan Cassan

12/8/2018 08:25:11 am

Having experienced the deminishment of dementia on the end of life with both my parents, I was heartened by the glimpse I had that even that ravaging disease cannot conquer a great spirit. When I visited the care home with my friend to see her aunt, we always knew where Marion was. From across the room or down the hall the sound of laughter and excited voices would signal her presence. Seeing this gives me hope that it is possible to stand against dementia and retain joy in life. There was no point ar which Marion Woodman stopped being an inspiration to those around her.

Reply

Ninian Mellamphy

18/8/2018 10:13:43 am

Congratulations, Herman. A fascinating blend of biography and autobiography!

Reply

18/9/2018 07:21:19 am

A very fine essay Herman, full of humour, wisdom, and fresh details. Inspiring! You have done a remarkable job of distilling their lives into a coherent form, which is helpful to me as I begin to attempt do something similar with the film.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed