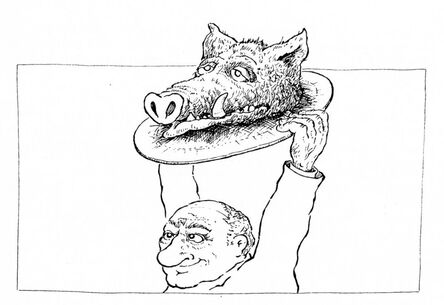

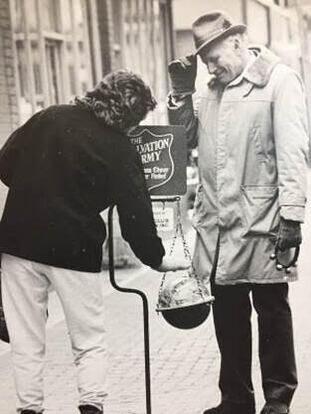

Illustration: Roger Baker Illustration: Roger Baker LONDON, ONTARIO – This week I delivered a paper for our first meeting in almost three years, entitled A Personal History of the Baconian Club in Four Obituaries. A THIRTY-TWO month interruption in the proceedings of this rather unlikely club that I joined thirty-two years ago has been raising some existential questions and challenges in my mind. Like, why did I join this club in the first place? If I had just come upon it for the very first time, would I want to join the Baconians today? And however much I have valued my membership in the past, is it possible to put any social consortium into suspended animation for almost three years and then fire it back up in the expectation that it will carry on as it did before or even function at all? (And that disconcerting question is one that’s being asked about an awful lot of our institutions right now – governmental, educational and religious – and I can’t say that the answers which are emerging are particularly reassuring.) If living members who were on the ground at the time of my investiture can now be counted on the fingers of one hand . . . and frankly, if we’re talking about relics who still make it out to most meetings, only one digit is required . . . and if my own status has evolved over those years from excitable, yapping Baconian pup to that mangy mascot who snoozes in the doorway and farts when you try to step over him . . . and, as the old saw goes, if you just can’t teach an old dog new tricks . . . well, isn’t it about time to haul my carcass out of here and let the younger mutts get on with their own bewildering hijinks in an unencumbered way? In tussling with these questions about Baconianism and belonging, I have been revisiting a handful of memorial tributes I have written over the last nine years to members who’ve passed away. In a happenstance which explains the wisdom of our in-session custom of addressing one another by our last names, three quarters of these remembered gents were named ‘Bill’. The first of these gentlemen I only knew through the Club. The second was mostly through the Club. The third was a very good friend who I brought into the club. And the fourth was a man I’d known at a bit of a distance for most of my life but only really came to appreciate when I watched how he operated in the context of the club. In one of these reminiscences in particular, the club plays a decidedly secondary role but I’m hoping these sometimes quite intimate portraits will be of interest to those of you who only knew them as Baconians. Our first obituary hails from December of 2013 and appeared in The London Yodeller.  BILL CORFIELD (1920 – 2013) BILL CORFIELD (1920 – 2013) BILL CORFIELD died earlier this month at the enviable age of 93 and from all accounts was in possession of his faculties and his curmudgeonly wit right up until the end of the very last lap. The two passions of his life were writing and flying - or ‘piloting’ - as his son Geoffrey was careful to call it so as to distinguish it from the rather more passive activity most of us experience when we fly. Bill was licensed to fly a plane before he was similarly accredited to drive a car and was a pilot instructor during World War II for the Royal Canadian Air Force when he was in his early twenties. Incredibly he last took the controls of a plane for a short flight at the age of ninety. At the mid-December gathering where family and friends assembled to share their memories, Bill’s other son, Paul, recalled a family trip to Britain which included a visit to Bill’s birthplace in Redditch, Worcestershire. Renowned in the 19th century for its dominance as a world supplier of sewing needles and fishing tackle, by the time of that sentimental pilgrimage one Friday in 1963, Redditch fancied itself as a model for modern town planning and to that end had knocked down the entire block of row houses except the one at the very end that Bill had been born in. Bill marveled that if they’d slated their visit for the following Monday, there would have been nothing left to show his kids. What was left looked depleted and small to his middle-aged eyes, including a low stone wall that Bill remembered jumping off as a toddler while holding onto an opened umbrella; an exercise he regarded as his first exploration into the dynamics of flight. No sooner had the war wrapped up than Bill landed his dream job as the pilot/reporter for the London Free Press. Once again ‘landed’ (though it has appropriate aeronautic overtones) is too passive a term. Bill conceived of the job himself and convinced Free Press publisher Walter Blackburn what a great thing it would be to have a company plane and a reporter to fly it and he also pointed out the fire sale prices that were then affixed to all kinds of slightly used aircraft that was lying around after the war. Bill flew the ‘Newshawk’ from 1945 to 1952, once shattering office windows along Richmond Street just north of Dundas when he flew dangerously low so a photographer could snap a not-very-elevated bird’s eye view of the Free Press building. Bill then worked as the director of public relations at Labatt Breweries from 1957 to ’65 (“Take 5 for 50,” was one of the slogans he concocted) and finally established his own public relations business, Corfield Associates, that operated out of an office at 360 Queens Ave. for almost 35 years, not closing up shop until 1999. And always, on the side, Bill wrote his books. There were a couple of wartime thrillers that got picked up by the British publisher, Robert Hale, in the 1970s. Geoffrey speculates that if his dad had stuck with that genre he might have been able to establish himself as a name to reckon with. But Bill wanted to tackle other kinds of work as well – mostly nonfiction – and didn’t return to thrillers until the mid ‘90s when he gathered three linked novels of wartime espionage featuring his hero/pilot Tony Campana – Buried in Spirit, Buried at Last and Buried Face Down – and published them himself in a bumper edition entitled Buried Together. There were military and aviation histories, biographies of publishers and printers, a book on scouting aimed at young boys called Keen for Adventure (with illustrations by London father/son artists Clare and Kevin Bice) and a fascinating array of books on different aspects of local history. My favourite of these is a beautiful little hardbound volume of sixty-five pages from 1992 documenting the war effort in London called The Home Front which is packed with charming period photographs from the Free Press. I first met and primarily knew Bill through the Baconian Club; London’s oldest club that has been holding its fortnightly meetings for more than a hundred and thirty years and is the only club in town that still limits its membership to men and is magically able to get away with it. Originally founded as a forum in which aspiring lawyers, writers and academics could hone the parry and thrust of debating skills, most sane women find the tenor of the club pointless and more than a little repellent. There are no social or business advantages to be gained by joining the Baconians but in refreshing distinction to all the other early London social clubs, there have never been any racial or religious barriers either. Shop talk is strictly forbidden at all gatherings. Baconians are discreet about their political allegiances and express no curiosity about one another’s private lives. No one ever passes around pictures of their grandkids or talks about their feelings. But if you’d like to hear an erudite paper on the history of lighthouses or the structure of Alfred Lord Tennyson’s In Memoriam and then hear a bunch of men vigorously comment on that paper’s strengths and weaknesses, then we just might be your ticket to dreamland. In his obituary of his father, Geoffrey recounted the time his father thanked the guest speaker at a Baconian Winter Banquet who’d been banging his gums for forty interminable minutes about some marvelously dubious innovations in education. This was around the time when the London Board of Education’s motto was “success for every student,” and the speaker had nothing much to say about imparting knowledge and lots of stuff about celebrating the specialness of every student. Bill ‘thanked’ our speaker so severely that his mouth repeatedly flopped open in disbelief (giving him the appearance of a goldfish at feeding time) until he could stand no more and fled from the building – some said in tears – subsequently mailing back the shredded cheque of his speaker’s honorarium. At our next meeting the club treasurer lamented, “If we’d known he wasn’t going to cash it, we all could have had more wine.” I was thirty-eight when I joined the Baconians whose average age at that time was about seventy. Most of these guys had been through the war and had fascinating stories to tell about making their way through a far harsher world than I’d ever known. And the open-hearted, no-nonsense way they interacted with each other struck me as wonderfully un-clique-ish. What I most admired about these old scrappers – and right from the beginning I regarded Bill Corfield as the Baconians’ purest emblem or type – was their utter refusal to pay any sort of lip service to pieties or sentiments or social agendas which they themselves didn’t subscribe to. They didn’t demand that everybody be cut from the very same cloth. They sure weren’t. The variance in their backgrounds was boggling. High born and low born. Christian and atheist, Muslim and Jew. Recent immigrants and fourth generation Londoners. Kids who’d left school at the age of fifteen and fully accredited doctors. At the same meeting you could hear a paper delivered by a pig farmer and a university department head. With most of these guys, so long as you didn’t presume to tell them how they ought to think, you could earn their respect by competently and reasonably arguing your own corner. I’ll always be grateful to the Baconians and Bill Corfield in particular, for helping me develop the backbone to not allow my own convictions to be steamrollered on those occasions when ‘going along to get along’ might be the socially expected thing but would cost me more than any bland appearance of accord is worth. This next one which I entitled, A Gentleman of the Old School, was posted on my Hermaneutics blog in May of 2019.  FRED KINGSMILL (1928 – 2019) FRED KINGSMILL (1928 – 2019) BACK IN THE LATE ‘80s / early ‘90s, some incarnation of our downtown business association got it into their heads that they needed to define the precise boundaries of downtown London. No doubt there was some issue about membership dues or eligibility for tax breaks that made such tortuous calculations seem necessary. But merchants and Londoners generally (there had been dark mutterings in the press) were starting to chafe at the exclusionary, snobbish overtones of the whole exercise until the gentle elder statesman of downtown shopkeepers, Fred Kingsmill, stood up at an association confab and contributed his two cents’ worth: “I always think of downtown London as being anywhere within the sound of St. Paul’s bells.” No, Fred’s wistful formulation couldn’t be adopted as a solution to their territorial quandary but – as so often happened when Fred chimed in with his ever-gracious perspective – tensions dissolved and attitudes softened and the discussion resumed on a more historically informed and distinctly human plane. I was reminded of his characteristic observation last Saturday morning as I cycled into town for Fred’s funeral and, turning into Fullarton Street at Eldon House, I could hear the bells of St. Paul’s Cathedral two blocks to the east tolling out the knell as the last of the mourners filed in through the big front doors. The church usually reserves a knell of that kind for the deaths of monarchs and statesmen and other momentously solemn events like a declaration of war. They bent that tradition for Fred because of his family’s long association with St. Paul’s and its bells. In his sermon the Reverend Paul Millward informed us that on Christmas Eve of 1935, Fred’s father was the first to ring the bells as they’re currently arrayed in St. Paul’s tower. And young Fred – born Thomas Frederick Kingsmill; he didn’t go by his middle name until he was an adult – often helped his father out with bell-pulling duties. It’s a tradition for ringers to engrave their initials or names on various posts and beams and Rev. Millward had gone up in the tower last week with some of Fred’s family to see if he’d ever left his mark in that way. Nothing turned up during that first visit and then Rev. Millward thought to head back up there and close the door, in the way that bell ringers do just before they commence their musical work. And sure enough, there it was on the back of that little door: “VE Day 1945 Tommy Kingsmill”. Fred would have been 17 years old. Thomas Frederick Kingsmill was the fourth generation of his family to operate Kingsmill’s department store. One of 23 different dry goods stores in London when it first opened on Dundas Street in 1865, Kingsmill’s distinguished itself from the very beginning for its select and wondrous stock of British woolens, linens, draperies, carpets and china. The store came of age with London and because its operation was always a family concern, Kingsmill’s never went in for the sort of corporate overhauls and re-brandings which erase any trace of originality or tradition in so many other stores. Right up until the end of its almost 150 year run - and despite two major fires in 1911 and 1932 - the hardwood floors remained intact as did the stamped tin ceilings and the Victorian elevator complete with a full time operator. Also still in evidence – though not so extensively used in an era of computerized sales – was the pneumatic tube system which linked the store’s 26 different departments to the sales office and sent all cash and paperwork zipping overhead in little cylinders. In his marvelous talk of remembrance, the Reverend Keith McKee told about the day when Fred was aghast to see a customer about to leave his store with an unwrapped Waterford vase poking out of their shopping bag. “Did nobody offer to wrap that for you?” asked Fred who then bundled it all up in tissue, and sent the customer on their way with his sincerest apology. Fred then took up this oversight with his staff who assured him that if they had sold a Waterford vase that day, they most certainly would have wrapped it; that Fred had just given the VIP treatment to a shoplifter. The competition was mystified at how Fred’s great, great grandfather, the Tipperary-born Thomas Frazer Kingsmill (1840–1915) so unerringly won contracts with all the best British suppliers and always knew which new products and lines to feature. Certainly Thomas Frazer made more buying trips to Britain than any of the other London merchants; sailing out of Montreal to Liverpool on CPR liners as many as four times a year. A sub-headline on the report of his death in The London Free Press said he, “CROSSED THE ATLANTIC OCEAN OVER 140 TIMES”. But the real secret to Thomas Frazer’s uncanny success was that even when he was at home with his wife and kids at their Belleview farm just north of the city (on land which would eventually be sold and developed as part of the campus of the University of Western Ontario), there was a second Mrs. Kingsmill on site in Britain making the rounds of manufacturers’ showrooms and placing orders for the store. It was a brilliant arrangement that gave Kingsmill’s a major advantage over all the other London merchants. Bigamy is a notoriously demanding and expensive crime to pull off for any length of time – even if you have the inclination or the ambition, who’s got the energy? – but Thomas Frazer managed to elude detection for the duration of his life. I found out about Thomas Frazer’s imbroglio in the early 90s while researching a whole slew of historic London biographies for a book that was going to be published to coincide with the unveiling of the People and The City sculpture (at the corner of Wellington St. and Queens Ave.) by artists Stuart Reid and Doreen Balabanoff. The information didn’t seem to be written down anywhere and it wasn’t talked about generally. But if they knew you were digging around in the archives anyway, librarians and other writers with a historical bent would sort of lean in and say, “So I guess you know about Thomas Frazer and his . . . uh . . . little trans-Atlantic subterfuge?” I had come to know Fred in a social way by then and subtly tried to get him to talk about it a little. He didn’t take umbrage. He didn’t deny it but he wasn’t going to augment my hearsay knowledge with any solid details either and it was pretty clear that he’d be just as happy if I kept it under my hat. And then when the proposed book on ancient Londoners ran into a budget shortfall and got boiled down to a much tinier booklet, I thought, “Yeh, Fred doesn’t need the grief. I’ll sit on it too.” And I wouldn’t be blabbing about it today if Fred hadn’t come to terms with it himself in recent years and spoken about it in some detail at meetings of the Baconian Club. After Kingsmill’s closed in 2014 and the building was purchased and transformed into a satellite campus of Fanshawe College, Fred gave a couple of utterly candid talks to our club about the history of the store and the eccentricities of his mercantile progenitors. I recognized a similar defusing of the scandalous past when I recently visited Australia where the descendants of 19th century Britons who’d been deported to a penal colony half away around the globe, were no longer so circumspect about acknowledging the criminal misdeeds of their forbears; in fact they were rather proud of them. Closing up the store definitely removed candour’s primary deterrent for Fred. But there also seems to be a term limit of about a century and a half to any scandal’s capacity to bite. When enough time has passed, infamous relatives can actually begin to take on a certain fascination and cachet. Not only can you talk about the rogues in your family tree with reputational impunity; you might even arouse envy among your contemporaries who secretly wish their forbears hadn't all been such four-square dullards. My greatest debt of gratitude to Fred is for introducing me to the Baconian Club. He’d been reading my stuff in the paper and enjoying it and contacted me in 1988 in his capacity as that year's president to see if I’d be interested in giving a talk at the midwinter banquet of London’s last remaining men’s club. Now 135 years old, the Baconians started up as a fraternal organization where young lawyers, journalists, teachers and doctors could hone and develop their skills as speakers and debaters. The talk I gave that night – entitled Towards a Forest City Mythology – was a lighthearted romp through London history where I explored incidents from the city’s past which I thought were reflective of some of the world’s great legends and myths. (I still think Slippery the Sea Lion as Sisyphus was pretty inspired.) Fred had warned me that Baconians could be utterly brutal to guest speakers they didn't like and London lawyer, Sam Lerner, did not disappoint; delivering a gleefully sadistic evisceration of my performance that was almost as long as my talk. Or does my memory exaggerate the duration of that eye-watering ordeal? I was stunned to have provoked such a tirade and can’t say that I ever did warm to Sam. But even in the depths of that merciless chewing out, I recognized the rare value of this company of men who could be counted on to grapple with ideas in an atmosphere where absolutely no holds were barred and I joined the club two years later. Thankfully, not all Baconians come on like Genghis Khan, and Fred was revered as one of our most obliging and winsome members. In his tribute at the funeral, fellow Baconian Keith McKee recalled how often Fred would begin some observation with the word, “Incidentally”. A phrase I particularly associate with him, uttered as he was about to consider an alternative perspective on some matter, was, “Now, in fairness”. Both phrases bespeak a habitual graciousness and thoughtfulness – a generous broad-mindedness and openness to other points of view – which were hallmarks of the Fred Kingsmill I knew. No small part of the fun of the Baconian Club is our po-faced regard for the conventions and etiquette of formal meetings. We address each other by our last names. You must be acknowledged by the president before you speak and you must stand up when you do so. This last year, Fred was granted a dispensation on the rule to stand as he’d been taking longer and longer to rise from his chair, and would self-deprecatingly say as he struggled to an upright position, “Leaping to my feet.” In Fred’s obituary notice his family thanked “everyone who made it possible for Fred to spend his final days at home.” That was a blessing for everybody involved and a truly just reciprocation. Over all the years I knew him, Fred was the mainstay of an unsung organization called the London Consistory Club which provided hospital beds and walkers at no cost to anyone who requested them, with Fred overseeing their delivery to people’s homes in Kingsmill’s trucks. On the way out of the funeral service, the St. Paul’s bells started up one more time with a recessional of Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God Almighty. And it occurred to me that perhaps our city’s oldest church hadn’t really bent their tradition so very much out of shape when they offered up that knell for Fred. If you don’t think in terms of an empire or a country but instead consider the honour and service that this private citizen unfailingly paid to the city that grew up around his family's store (and within the sound of those bells) then there really was something rather royal about Fred Kingsmill. And here from April of 2021 is the saga of the very good friend I brought into the club.  BILL McGRATH (1936 - 2021) BILL McGRATH (1936 - 2021) IT WAS SOME TIME in the fall of 1980 when I met Bill McGrath for the first time as he poked his head through the office doorway while I was dropping off my latest essay to Norm Ibsen, the London Free Press’ editor in charge of the opinion/editorial and book review pages. “We seem to be running something by this guy every week,” Bill said to Norm, indicating me with a nod of his head. “Isn’t it time we had a picture?” Norm agreed and Bill took me out to the less cramped hallway and set me up against a clear section of wall where a reasonable amount of natural light leaked through and took my photo with his Polaroid. “I’m really glad we’re running your columns,” Bill told me with a conspiratorial smile as we stood around waiting for my lovely visage to materialize on the murky card that emerged from the base of his camera. He explained that he would be sketching out an inky likeness of my face to accompany my articles; and that he did all the drawings of writers that appeared on the editorial pages; a journalistic tradition that was already passing out of fashion but which the Free Press wouldn’t relinquish for another decade. I told him that I didn’t know what all the writers he’d depicted looked like in real life. “But your Art Buchwald is aces.” That day we established a “how-do-you-do?” sort of acquaintance which held up for the next fifteen years. This dramatically deepened into friendship one chilly night in October of 1996 when both of us found ourselves at real crossroads in our lives. I was attending an Opus Dei retreat for men at St. Stephen’s of Hungary church in old South London when I noticed Bill sitting in a pew two rows in front of me. Always a handsome dog with his thick weave of hair and a kindly face, that night he was wearing a snappy blue jacket with some light fur trim on the collar. At a couple points in the evening, I caught myself idly staring at his profile as he huddled in prayer, envying him his solid and respectable station in life. Now there was a guy who’d played his cards well . . . unlike some losers I could mention. I knew next to nothing about Opus Dei but decided to attend this retreat because I badly needed some spiritual ballast in my life to weather the storm I knew was coming. At the age of 44, I was about to bail as editor of SCENE magazine which then constituted the mainstay of my livelihood. The publisher had fallen under the spell of a consultant who was set on remaking our arts and opinion journal into a breezier entertainment weekly. The scaling down of our magazine’s scope had been coming on in humiliating stages and I was having major blowout arguments with the publisher every week as I was forced to cut columns and let some of my favourite writers go. My wife who was doing all the layout would find a way to hang in for three or four more issues after I walked. But one way and another, the end was coming and our household was in for a world of pain. What I didn’t know until Bill and I fell into a long conversation outside the church at the end of our retreat, was that he was about to chuck all fifty-two cards in his well-played deck up into the air as well . . . though he, at least, would have a pension when all those pieces fluttered back to earth in a heap. At the age of sixty, and after thirty-five years at the Free Press where he’d worked himself up from a draughtsman in the ad department to editorial art director in charge of the overall look of the paper, Bill had decided to accept an early retirement buyout offer. The Freeps was starting into its downward trajectory of successive contractions by then and wasn’t the rewarding place to work that it had been. He still loved the game of designing a paper but knew that the days of innovation and leeway were a thing of the past there. Bill had recently been invited to Spain to share his expertise with some newspaper publishers and art directors and found that junket thoroughly invigorating. By talking with people who were so excited by the possibilities of what could be achieved through the arrangement of words and graphics and pictures on a page, he was reminded of what drew him to newspaper work in the first place. And when he wasn’t consulting with other newspaper professionals, he was dashing all over the country on visits to Spanish churches. Those ancient houses of worship were another revelation for this orphan boy from Northern Ontario who’d converted to Catholicism in order to marry a young nurse-in-training, Marcia Van Domelen; awakening a hunger to deepen his commitment and explore more deeply the history and traditions of his adopted faith. Bill often talked with head-shaking wonder about the Mass he attended at the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia which serves as the grand terminus for pilgrims walking the Camino de Santiago. This magnificent cathedral has a censer as big as a small boat which is loaded up, ignited and then elevated into the central dome on chains where it trails great cloudy plumes of incense as it careens and swings from side to side. It is said that this immense censer was originally designed to act as a sort of celestial air freshener in a space that was regularly invaded by whiffy pilgrims who’d been hiking through the Pyrenees and sleeping rough along the way for weeks and even months. Confronted with the spectacle of this flying, smoking ship of the air, Bill the Catholic tourist was flooded with a whole new level of awe for a Church that would orchestrate something so daft and reckless and unspeakably beautiful as this. Though there were sixteen years between us and I alone was in a state of financial peril, when we forged our deeper friendship that night behind St. Stephen’s of Hungary Church, we both were perched on the rim of the great unknown and summoning the strength to leap. We were seeking out new places where we could worthily pursue our trades and were determined in every aspect of our lives to align ourselves more completely with our faith. The first great project we hurled ourselves into – putting together the prototype for a substantive weekly newspaper that would showcase the work of a lot of the good people I’d had to let go from SCENE – came to naught. We had some definite nibbles but no backers with sufficiently deep pockets stepped forward to help us float it. By the next spring Larry Henderson had taken me on as associate editor of his Catholic monthly magazine, Challenge, and with Bill at the wheel - and taking photos and making sketches - we’d head out all over the province and into the northeastern States to work up stories on pro-life conferences and marches, talks by various Catholic luminaries such as author Michael O’Brien and EWTN foundress Mother Angelica, publishers’ trade shows, a Pan-American conference on religious rights and a four-day Opus Dei retreat. At one of these multi-day confabs in the fall of 1998, we were sharing a room at some hotel near the Pearson Airport when I jolted myself awake one morning by snoring with particular vehemence. Bill's bed was empty; he'd already showered and dressed and nipped down to the lobby to snap up that day’s edition of the recently launched National Post which he was poring his way through at the little desk in our suite. Bill adored the early Post for its content and its look and the challenge it posed to newspapers across the land to try a little harder. “I’m sorry,” I said. “I must’ve been snoring pretty loud.” “Not at all,” he said, looking up from his paper with a smile. “Just a gentle purr.” This was a line so preternaturally gallant that I swiped it and invoke it on those exceedingly rare occasions when my wife expresses a similar anxiety. Later that same year Bill laid out and designed my first book for Elmwood publishers, In Good Faith, and did similar work for almost every book that London house has subsequently published. The last book of mine which he saw through the press was 2010’s No Continuing City. We took our time with that one; both because we lavished extra attention on every aspect of its design and flow (and it is, I think, the most elegant of our productions) and also because Bill, now well into his seventies, wasn’t so inclined to put in marathon twelve-hour shifts at his computer terminal. When Bruce Monck launched The London Yodeller in December of 2013, I came on as editor and endured the wildly eccentric proclivities of his chosen layout man until the doofus nearly sabotaged the fledgling enterprise with a lawsuit-worthy issue that came out in February of 2014 while I was in Australia. So that was the end of that chap’s art-directorship and in a big hurry, Kirtley offered to save everybody’s bacon by getting back into the layout biz seventeen years after her stint at Scene. She was, of course, ably and calmly coached through the nail-biting minefield of her first Yodeller issue by Bill. And he remained her go-to guy for the occasional solving of quandaries throughout the three-year run of that uniquely lovable magazine. And just as importantly, he regularly gave her the kind of informed feedback on her job performance that only he could provide. The parameters of our friendship were such – working on journalism assignments out in the world; meetings at my place of our Christian men’s reading group, the Wrinklings; meetings of the Baconian Club at Chaucer’s Pub – that I never really got to know Bill’s family well. His three sons (only two of whom I think I’ve formally met) were grown and launched into the world by the time Bill and I became a tag team. I’d bump into his wife, Marce, from time to time, and a genial soul she was, but I don't believe we ever had a sustained conversation. As a born Catholic, I think she was a little bemused by Bill’s growing preoccupation with his faith. It’s not that she didn’t value it or ever took the Church for granted. She was a tireless volunteer at the McGraths’ home parish of St. John the Divine; which the pair of them played a pivotal role in establishing shortly after they arrived in London. But Marce just got on with her faith and didn’t feel Bill's need to sit around gaping at the mystery and splendor of it all. The most amusing example of the McGraths' disparity of approach to matters divine came somewhere around the turn of the millennium when they headed out on separate dream vacations to places the other could never be persuaded to go and Bill made his way over to the Holy Land (later regaling the Wrinklings with a splendid slideshow) and Marce flew down to Vegas to play the slots. The time when I had the most to do with Marce was in the wake of her sudden death in August of 2003. Hers was the first Catholic funeral I ever attended and I was astonished – in a good and heart-wrenching way – at what a powerful ceremony it was. At a prayer service at the funeral home the night before the Mass, I felt a little lightheaded when I first noticed there was a kneeler set up right at coffin-side. The casket, of course, was open, and anyone who knelt there was brought intimately close so that they were literally whispering into her ear as they prayed. Kids, even those who could scarcely toddle, were not kept at bay or barred from any part of the ceremony. The next day it was Bill and Marce’s grandkids who carried the Eucharistic gifts forward to the coffin at the foot of the altar and passed them over to the priests. Any friends of the family who managed to hang onto their composure through that, soon lost it when the kids returned to the pews in tears to be picked up or hugged by their sobbing parents. I would say it was about a week after that that Bill and I sat together in his car in the shaded parking lot behind a bank near the university gates (I was taking over from him as Baconian president and we had to sign some transfer notices for the club’s account) and he talked to me for more than an hour about how much that funeral had helped him make it through the hardest thing he’d ever endured - not that his mourning was over by any stretch - by keeping him focused on his family and his faith and reminding him that he wasn’t alone in his grieving nor in the hope of ultimate reconciliation. In 2017 Bill succumbed to a bout of the gout that really knocked the stuffing out of him, sapping his strength, causing him to lose weight and turning that beautiful head of hair kind of frizzy. He also started reacting badly to wine and I valiantly stepped forward to haul away the dozen cases of pretty decent homemade Merlot he had stashed in his basement. Bill went into care in his own monitored apartment at Windermere on the Mount shortly thereafter. He could be visited there any old time and still made it out to important meetings of the Baconians (last turning out for the mid-winter banquet of 2020 just before the Wuhan batflu suspended operations of the club) and the Wrinklings (struggling with our stairs for the last time to attend September's 25th anniversary gala for which Kirtley baked a cake decked out with sparklers.) Frequently isolated by the on-again / off-again lock-downs of the last fourteen months and discouraged when every slight improvement in health was soon succeeded by a greater deterioration, Bill became increasingly listless, sleeping away great quantities of each day and taking minimal interest in food. As Holy Week got underway he told his sons that he was ready to die and had them ask Father Adam Gabriel (who he'd known from the earliest days at St. John the Divine) to come and administer the Last Rites, which he did, appropriately enough, on Good Friday. Then his son, Dan, sent out a letter to Bill's friends, telling us where things stood and that Bill would love the opportunity to say goodbye to us. Now that he had been declared palliative, Dan said, it was a lot easier to get in for a visit. His door was never locked. Just knock a few times and go in. Dan warned us that we might have to wake him up. "He wants to see you. You may have a great chat for 20-30 minutes and he may fade out a bit. He is still listening, just nudge him once in a while." Kirtley and I got up to see him on Wednesday April 7th, at about five-thirty. We still had to get decked out in the full bee-keeper's outfit of beastly PPE-wear to move through the public hallways but were able to shed its clammier components once we got up to his room. Bill was asleep in his recliner when we first came in but woke up as soon as we said hello and gave us the warmest smile. We stayed with him for a little over an hour and found him to be surprisingly responsive. He drifted off to sleep on us once but was easily called back and his brain was firing away with pretty impressive efficiency, dredging up names from his early life in Timmins and Kapuskasing and recalling his courtship with Marce. At one point he did a really good impersonation of Father Gabriel telling him that just because he’d given him the Last Rites, "You are under no obligation to die right away." I thought about heading out after twenty minutes and then forty minutes, but the way Bill was smiling and yakking away, I knew it wasn’t necessary. Indeed Kirtley was so struck by his level of engagement and animation, she found it hard to imagine Bill would be parting any veils any time soon. We had a wonderful hour full of reminiscence and laughter and more tender expressions of gratitude for friendship and faith in God. I knew I wanted to go see him one last time but I must admit that I was dreading it in many ways. And as we left his room I was almost overwhelmed by what a sublime pleasure it had been. And when he died ten days later I was so thankful to Kirtley and one of the Wrinklings for helping me find the courage to go. When Dan showed up at about a quarter to seven, he remarked on how lively his father seemed. “It must be because it’s his birthday,” Dan said. What an honour it was to have that time with my good friend Bill McGrath as we looked out over the edge of eternity on his 85th and final birthday. And finally, appearing on my blog just a year ago last month, is my remembrance of Bill Paul.  BILL PAUL (1955 – 2021) BILL PAUL (1955 – 2021) LONDON LOST her unofficial and utterly ubiquitous town crier earlier this month at the age of 66. Though he was not a man I ever came to know well and (other than a love of London lore and the operas of Gilbert & Sullivan) shared few interests with, Bill Paul did me a good few favours over the nearly fifty years of our acquaintance; favours which I did a singularly crappy job of acknowledging, let alone repaying. I think we both thought at first that we were going to get along better than we did. That I was three years older needn’t have been an obstacle to friendship, even when we first met in our twenties; never mind later in our lives when such a tiny gap doesn’t signify at all. But somehow I always did feel significantly older than him. Though I liked him and admired his energy and drive – and though I hardly thought of myself as Sammy Sober-sides and have had certain dour souls counselling me all my life to ‘grow up’ or ‘get serious’ – an awful lot of what he got up to didn’t appeal to me very much and, when you got right down to it, struck me as kind of frivolous. He first sought me out in 1978 to pick my brain about some consulting work he was doing with London high school students involved in publishing school newspapers. Bill had been the editor of Central’s newspaper back in the day. I had edited South’s newspaper a few years before that and by the time we met, I had written a whole whack of fiction (and even published some) and, newly married, was making my first inroads into the wonderful world of newspaper and magazine journalism in the hope of being able to earn my living that way. At that time he was lavishing most of his attention on what struck me as rather crudely compiled fanzines about comic books and science fiction novels and movies. The only child of wealthy parents, Bill never married and wasn’t so focused on finding a way to earn his crusts. His father was a psychology prof at Western and a researcher and campaign adviser to the Liberal Party in the ‘60s. Many years later I would hear Bill’s story about the time when he was seven or eight years old and was pressed into serving canapes to a bunch of Liberal party worthies who were assembled at his parents’ home. In a herky-jerky moment with a generously laden platter, Bill managed to knock a shrimp onto the floor and spill cocktail sauce onto Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson’s trousers. Picking the shrimp up and wiping it off, he assured Mr. Pearson that it was “still good”; luckily eliciting a laugh from the PM and an ‘I’ll-talk-to-you-later’ glare from his mom. Bill had a coterie of young enthusiasts who worked with him on those fanzines and they would travel all over the province and into the States to attend conferences and trade shows and every summer he would host the London Annual Fantasy Festival (LAFF) at his parent’s thirty room pile, Hazelden Manor, which backed onto the bluffs across the river from Springbank Park. Actors (never the A-listers) from shows like Battlestar Galactica and Star Trek and creators of cartoons like Howard the Duck would be featured at these weekend-long house parties that drew hundreds of people and must’ve been a lot of fun if you were into that sort of thing. When there was a requirement to supply some kind of security personnel for a function that Bill and his pals were hosting, he dubbed his crew the Laff Guards and under that name they hired themselves out – or, frequently donated their services – as combination entertainers, security guards and masters of ceremony for all kinds of parties and charity events and openings. For a period you could even call the Laff Guards when you wanted to send somebody a singing telegram. Bill had a weekly radio gig for thirty-eight years; an interview program called Straight Talk on the Fanshawe College station, 106.9 FM. And for twenty-five years he hosted a weekly interview show on the Rogers Cablecast channel and had me on whenever I had a new book to flog (and Bill, God bless him, was that rarest of interviewers who would actually read the book) and once to showcase one of my rather desperate musical consortiums (singing all our own songs that featured the same six chords) called Little Kenny & The Spit-Ups. My relationship with Bill suddenly went pear-shaped in 1980 when the horror movie spoof, Attack of the Killer Tomatoes, was screened for the first time in London at the New Yorker repertory cinema on Richmond Street. That screening occurred during the very first year of my three and a half decade run as a regular freelance columnist with The London Free Press. As that deliberately cheesy movie had already achieved a milder semblance of the cult status which attended The Rocky Horror Movie Show from a few years earlier – where rowdy fans turned out in costumes inspired by the film and made lots of noise throughout the show – I decided to trot along to the New Yorker with reporter’s pad in hand and see if I couldn’t get a column out of the spectacle. I had been a big fan of horror movies as a twelve and thirteen year-old and faithfully collected, assembled and painted up all of the Aurora monster models including Frankenstein, Dracula, The Wolf Man, The Bride of Frankenstein, The Mummy, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, The Phantom of the Opera, The Creature from the Black Lagoon, King Kong and Godzilla. But all that had been half a lifetime ago and any innate enthusiasm I might once have entertained for even a clever send-up of the horror movie genre had drained away. This grotesquely labored turkey of a movie – which might have made a decent seven-minute skit on Saturday Night Live – bored me sideways and I was straining just as hopelessly as this movie’s director to imagine how I was ever going to be able to crank out material of any interest whatsoever in my review. Being early days in my life as a columnist, I didn’t yet recognize that there are indeed times when a proposed subject turns out to be such a dud that you need to cut bait and go focus on an entirely different fish. But my editor was expecting copy later that night and I’d already invested so much psychic energy into priming my pump for a raucous take on this zany movie that I was determined to see it through. There was clearly no way to spin out a thousand words on this insipid film, so I turned my withering gaze to the audience instead: “Who are all of these people and what are they doing here? About a fifth of the audience seemed to be comprised of Bill Paul and his Laff Guards, a local, self-proclaimed comedy troupe most famous for having endured a long and collective existence without once managing to amuse anyone who wasn’t a member of the troupe. Bill and his squad of aggressively inane adolescents warmed up the pre-show audience by waddling around like drunken ducks and yelling ‘hello’ to one another, sporting a level of mindless merriment which is their immensely irritating trademark.” Out of mercy to me - as much as to you and the memory of Bill Paul - I will spare you the next couple paragraphs of my ill-tempered snark-fest. When I read the printed copy the next morning, I felt sick at what I had done to a man who’d always treated me with generosity. I heard through the grapevine that – surprise, surprise – Bill felt hurt and betrayed. And it was in the wake of that unworthy outburst that I formulated a policy I’ve tried to live by ever since. Whenever I find myself writing a piece where I'm really laying into somebody, I ask myself, “Would I be willing to sit down with my subject face to face and read out what I’ve written?” If not, then fix it up so I would or deep six it altogether. I would estimate that it was two or three years later that I met Bill again and we talked. The circumstances of our re-encounter were surreal and shocking, threatening and poignant. It was about 10:30 on a weeknight and I was standing at the bus stop at Wharncliffe and Mt. Pleasant, on my way in to my job as a night attendant at the Salvation Army Children’s Village, when I heard Bill's voice approaching through the parking lot behind me. “Is that really you?” he asked, in a most untypical voice that was laced in old anger and what I would soon discover was a very fresh infusion of pain. He’d been in to pick up something from the Laff Guards’ small office next to what is now the West Side Restaurant and chucked it into the back seat of his car before coming across the lot to confront me. “Of all the nights to meet you again,” he said, walking right up to me as I turned around to face him. I could see emotion tugging at the corners of his mouth but I didn’t yet know the half of what he was going through. “My mother died today,” he said and collapsed sobbing onto my shoulder. Perhaps it was easier to not have to see his face when his sobs had subsided a little and, my hands still set on his back, I said my long-considered piece. “If it’s any consolation to you at all, Bill, I know it’s the shittiest thing I’ve ever done as a journalist and I’ve always regretted it.” “Good,” he said in a voice of gruff satisfaction, which he raised a little to be heard above the sound of my bus racing past; not about to stop for either of these two weirdos hugging at the side of the road. “It looks like I’m going to have to give you a ride,” he said. “Where are we going?” We had a good healing talk on our way across town and in all of our subsequent encounters over the next forty years, Bill never alluded to my shabby stunt once, never treated me any differently than before; even had me back on his TV show to flog more books. One of his qualities that sometimes made Bill a little difficult for me to relate to was what seemed to be a stark incuriosity about religion. Conversationally he just wouldn’t go near that stuff. But a disinclination to talk about such things, didn’t preclude his unselfconscious embodiment of Christian virtues to a rare degree. Very few people I've personally known have been more charitable and forgiving. I don’t know if it was the ‘80s or the ‘90s when he started turning up – clanging bell in hand and bellowing out his quite melodic cry of "oyez, oyez oyez” – at every downtown festival or parade or cultural event; spiffily decked out in a tri-cornered hat and flamboyant waistcoat as London’s town crier. Sometimes I think he was hired for those jobs but usually he just showed up on his own accord so as to call such public occasions to order. And somewhere in that period he also started extending more personal greetings as well. Most years he’d phone me and literally thousands of other Londoners (even those who’d moved away to other locales) on our natal day to sing Happy Birthday. It is said that in a good year, he’d place nine thousand of those calls, trying to get it up to ten thousand so he’d make it into the Guinness Book of World Records but then losing another one of his booklets with lists of names and numbers and having to build up his data base once again. Playwright and theatre impresario Adam Corrigan Holowitz said that Bill once told him, “It's really hard to stay down if you spend two or plus hours a day singing Happy Birthday over the phone to people." I had the most to do with Bill in an ongoing way when he joined the Baconian Club about ten years ago. This last surviving men’s club in London which now meets eight times a year is known for the sardonic interplay of its members as they get together to listen to and critique one another's papers and readings. Bill gave a talk a few years ago, working from scribbled notes on a single page, that gave a wonderfully detailed history of radio in London; reminding me once again of the wealth of London lore he carried around in his noggin. And the more miscellaneous observations and comments he offered up there were always good-humored and notable for their utter lack of malice. It was also at those regular Baconian meetings that I came to realize what a physical and financial struggle life had become for Bill, though you’d never sense it from his demeanor which was unflaggingly cheerful. Something awful was going on with his legs as they started to bow out more and more, making it increasingly painful to walk which, in turn caused him to move as little as possible. And that, of course, spurred on an alarming gain in weight which then put more pressure on those poor messed up legs; a truly vicious circle. Even in his heyday one never knew how much of the work that Bill undertook actually paid but coming from a well-off family, that wasn’t such a concern; you knew he’d be all right. But in these last several years one didn’t get the sense that any safety net remained in place. His clothes were becoming shabby and he was living in a modest apartment in an old downtown house that no one but Bill ever saw the inside of. After Baconian meetings one of our members would drive him over to a pub on Richmond Row where he’d situate himself on a chair near the door until the wee hours of the morning, selling balloon animals to patrons for spare change. And doing so with such humour and charm that the desperation of it all probably didn’t occur to any of his customers. The last nineteen months of Covid lock-downs and social distancing wiped out that revenue stream for Bill. But, dying in his 67th year, at least he had the old age supplement to mitigate the poverty of sixteen of those isolated months. Two major revelations regarding Bill came to light for me at his funeral. One was his inclusion of a short prayer and scripture reading ("'I am the resurrection and the life'," saith the Lord . . .) before people went up to share their testimonials. The other. regarding a bequest he made decades ago was attested to by Bill’s friend and pro bono lawyer, Ed Corrigan, and radio announcer Skye Sylvain who got her first job in the biz working with Bill at 6X FM. When Bill’s full inheritance from his parents came through, he gave a cool one million dollars to the United Way of London. “He probably should have kept some more for himself,” Skye observed, acknowledging the dryness of his well by the end. Bill’s funeral was held at O’Neill’s, the same funeral home that handled Roy McDonald’s funeral in February of 2018 where – who else? – Bill Paul served as master of ceremonies. It’s a little uncanny how frequently these two gregarious, bearded renunciants - who each did without so many of the common conventions and comforts to live out their lives in their own ornery way - have been bracketed together in Londoners' reminiscences and reflections these last couple of weeks. For any sort of crowd to be accommodated in this time of the batflu pandemic, Bill Paul’s mourners had to assemble in the parking lot. Also there to kick things off by activating every tear duct in the lot, was music director David Weaver and the H.B. Beal High School marching band playing – but of course! – Happy Birthday. ***** SO THERE YOU GO. That concludes these idiosyncratic notes of fond reminiscence, compiled at a rather wobbly historical juncture when we remaining veterans of this wonderfully peculiar club are finally able to reconvene around this horseshoe table and hope to find a way to keep on flying . . . if not our freak flag exactly . . . then how about that rather grotesque platter we haul out for our banquets that is graced with the decomposing head of a wild boar? Oh, “those damned Bacon Boys,” as my sister-in-law witheringly calls us. Long may we carry on snorting and galumphing and prognosticating our way through the underbrush, helping one another make sense of our passage through this mesmerizing vale of laughter and tears.

4 Comments

Barry Allan Wells

13/11/2022 07:04:01 am

If women were allowed to join the Baconian Club as writers, lawyers and academics etc., it's doubtful there'd be any lapse in Baconian activity.

Reply

SUE CASSAN

13/11/2022 10:49:53 am

What a wonderful series of essays. Each of these lives so complex. Reminds me of the Japanese art of kintsugi, repairing broken pottery with gold seams. Instead of regretting or discarding the ups and downs and blows life brings, celebrate the cracks and flaws that make each even more unique. Here’s wishing the group all the best for reviving your fellowship. Ole hyvä, mies, as the Finns would say, you go guys!

Reply

22/11/2022 06:34:17 am

Interesting stuff. Where there´s a William there´s a way. Sent by Pianoverkstaden, Sweden, the company which sends small Bills.

Reply

Bill Craven

26/1/2023 10:47:23 am

Dear Herman

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed