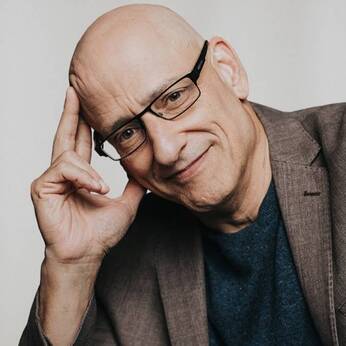

LONDON, ONTARIO – The world’s very first autobiography (as we understand that term today) also happens to be the great granddaddy of all Christian conversion narratives. Though it was first produced a mere 1,624 years ago (and is only one of an estimated 113 books that he wrote in his lifetime) such is the inquisitive, generous and downright playful cast of St. Augustine’s mind, that his Confessions remains more uncannily readable and relatable than a considerable portion of the religiously themed books that are published today. As a mid-life convert myself – thirty-two years old at the time of my plunge but intermittently fascinated by the prospect since the very dawning of self-awareness – I have always been interested to see how others managed to grope their way along the path to Christian belief. And in service to that abiding curiosity, I have probably read at least a hundred conversion narratives both before and since coming into the Church. Though the destination of each convert may be the same, it is the infinite disparity of approach that fascinates. And while there are no generalizations that hold up for all, I can’t help observing how often it is one of a seeker’s lesser-utilized faculties that finally pushes him into the zone of belief; leaving him feeling somewhat blindsided as to what just happened. There is the intellectual whose rational and methodical approach is suddenly blown to smithereens by an unaccountable mystical experience . . . or the constant reader who is finally convinced not by an exquisitely formulated argument but by a apontaneous gust of wind or the unpremeditated beauty of a wildflower . . . and then there's the less deliberate seeker who’s sure he isn't interested in such arcane matters at all until he hears faith denounced in a way that strikes him as false and unfair and inexplicably rallies to its defense. The appeal of conversion stories for lifelong believers has long been noted. They reacquaint such readers with foundational precepts they've probably taken for granted; revealing the richly compelling and logical appeal that Christian faith makes to any sincerely questing soul. Wanting to ring a fresh variation on all those essay collections in which assorted converts recall what drew them into the fold, publisher Frank Sheed compiled a collection of memoirs from lifelong communicants which he called Born Catholics (1954). And sure enough, it wasn’t one of Sheed & Ward’s better-selling titles. Not only did that book lack the crowd-pleasing aspect of the great quest boldly undertaken. It also showed how fiendishly difficult it can be to explain truths so deeply held that you've never had much cause to examine and explore them. It’s a quandary which St. Augustine himself postulated in Confessions: “If no one asks me, I know: if I wish to explain it to one that asks, I know not.”  ST. AUGUSTINE ST. AUGUSTINE I haven’t kept all of the conversion texts I’ve read, but seven I particularly treasure and revisit from time to time are Augustine’s Confessions (397) John Henry Newman’s Apologia pro Vita Sua (1864), G.K. Chesterton’s Orthodoxy (1908), Ronald Knox’s A Spiritual Aeneid (1918)), Thomas Merton’s Seven Storey Mountain (1948), Dorothy Day’s The Long Loneliness (1952) and C.S. Lewis’s Surprised by Joy (1959). Of the two Americans on that list, I haven’t got much use for anything else Thomas Merton wrote (his much-vaunted open-mindedness too often strikes me as instability) and I otherwise prefer Dorothy Day’s incidental essays to her books (which can nag more than they persuade). But those two titles are solid. And C.S. Lewis also sticks out as the only non-Catholic author in my pantheon of great conversion narratives. Writing in perhaps the last historical moment when Anglicans and Catholics shared a recognizably similar understanding of the faith, Lewis was remarkable in the way that all of his Christian writing – full of deep insights and brilliantly expressed – managed to steer clear of those areas where sectarian distinctions might muddy the view. Sticking to the larger themes of what he called “Mere Christianity,” to this day Lewis can be read with equal enjoyment and reward by Christians of any denomination. (Though a cottage industry in speculation has developed since his death in 1963 about which communion Lewis would have fled to once the Anglican church succumbed to its devastating series of increasingly incoherent synodal makeovers.) The other question which a quick peruse of my list might raise, is “Has Mr. Goodden read any conversion texts from the last sixty-two years?” While it is my general rule to take up any book (or music or movie) from the last half century with caution and care, I am not an utter Luddite in these matters. And it just so happens that so far this year I have read three considerable texts by Christian writers which hail from the last five years. Two of them are Augustinian-type memoirs specifically highlighting conversions and the third is a meditation on twelve important questions with far reaching moral implications that are too rarely asked today. I don’t know yet whether any of these books will ultimately take their place in my all-time pantheon of greats but all are worthy undertakings which I commend to your attention..  ANDREW KLAVAN ANDREW KLAVAN The first up is Andrew Klavan’s The Great Good Thing: A Secular Jew Comes to Faith in Christ (2016). About five years ago I first twigged to this bald and impish novelist, screenwriter and decidedly fearless commentator on culture, religion and politics (in about that order). His now-weekly podcast for The Daily Wire has become must-watch TV at our house on Friday nights. Though he didn’t finally make his way into a church until his fiftieth year, of these three writers, Klavan's trajectory to faith is the one that most closely resembles my own. Being roughly the same age, we share a lot of generational and cultural touchstones. I related to the strategies he undertook to make his way as a writer in the secular world without betraying his spiritual inclinations. At points when our so-called careers ground to a halt, we both resorted to an intense regimen of psychoanalysis – his Freudian, mine Jungian – and then found to our utter surprise that those supposedly psychological ministrations had opened up a much clearer pathway to religious belief. And perhaps most surprisingly - him being a secular Jew and all that - even when our metaphysical searches seemed to have fallen most dormant, the aching tenderness of each year’s Christmastide (to which he’d been exposed by his family’s housekeeper who loved him with a generosity his own mother couldn't muster) never left us untouched or unstirred. Klavan struggled for decades in his earlier adulthood with depression - not uncommon for innately funny people who have a real eye for the wild dysfunction in all of our lives - much of it attributable to growing up under two intelligent and talented parents who were hobbled by a faith they could neither believe nor discard; paying lip service to and observing the mandatory rituals of an inherited identity which embarrassed them and, they felt, held them back from self-realization. Reconciliation with a legacy as paralyzingly tangled as that took a good few decades for Klavan to work out, particularly when he found himself being increasingly nourished by the culture and predominant religion of the West which had done so much over the centuries to sequester and harm his forbears. Late in this remarkable book, parts of which zip along like a metaphysical thriller, Klavan drops a shimmering truth-bomb that pulls together into one audacious formulation the tragic antagonism between the cultures and faiths that have shaped his life: “There are some people who say that an evil as great as the Holocaust is proof there is no God. But I would say the opposite. The very fact that there is so great an evil, so great that it defies any material explanation, implies a spiritual and moral framework that requires God’s existence. More than that. The Holocaust was an evil that only makes sense if the Bible is true, if there is a God, if the Jews are his people, and if we would rather kill him and them than truly know him, and ourselves.”  TYLER BLANSKI TYLER BLANSKI I was initially intrigued by Tyler Blanski’s An Immoveable Feast: How I Gave up Spirituality for a Life of Religious Abundance (2018) when I saw the ads for this book by a writer I’d never heard of featuring two and three-sentence plugs by such Catholic heavy-hitters as Archbishop Charles Chaput, Peter Kreeft, Thomas Howard and Cardinal Raymond Burke. Then when I scoped out the opening page in a secondhand shop early this year, my interest intensified when I read that Blanski was born on the very same perishingly cold day in January of 1984 as our second child and only son. No, my astrological Spidey senses were not all a-tingle (I don’t actually have those in any pronounced form) but that arresting coincidence did provide an extra sense of connection with his story. Here was a young man mapping out the religious terrain as it might appear to my own children if they were ever to take up this search. That sense deepened a couple pages later when Blanski laid out the story which gives his book its title, recalling much the same stunt as our son got up to when his older sister persuaded him to run away with her because their parents were such meanies: “I filled a large red handkerchief with an apple and a sandwich, and tied the contents to the end of a long stick. I marched around the block with pride. Not knowing what else to do, I sat on the curb across the street from my home and I ate my sandwich. And as I was biting into my apple, I remember seeing my family sit down to dinner through the dining room window, and suddenly I felt foolish. Maybe I thought the world would sputter to a stop in my absence, that my family would be beside themselves with worry, but there they were eating dinner, as if nothing had changed. Flabbergasted, I shelved my pride and went home, and as I entered the dining room my mother cried and my father laughed and I sat down to a feast. This memory for me has become more than mere history; it is parable.” The 'immovable feast' which Blanski's parents set before him - and which he tinkered with and alternately developed or downplayed but never actually rejected - is the Christian faith. As teenagers his parents became what we used to call Jesus freaks. Cutting clean against the custom of the Age of Aquarius, they married young and had their babies young, raising them in an Evangelical household but always giving their children the leeway to think things through and work out their own destinies for themselves. One of the book's recurring jokes is how often Tyler returns for a holiday or the summer and no sooner announces how great it is to be back home, then one of his parents answers, "That's fine, Tyler, but you can’t stay here." I originally anticipated that the "spirituality" which Blanski says he "gave up" in his book's subtitle was going to be the usual new-age codswallop which permeates American culture today and particularly infests the young. But Blanski's religious formation was a little too solid to let him fall for that self-serving goo. No, he's referring to Anglicanism, the outer forms of which appear so solid and traditional - the beautiful chapels and liturgy, the robes and the candles - but the core of which is alarmingly malleable. Newly married with a child on the way, Blanski is on the brink of being ordained an Anglican priest when he finally chokes on that church's authority deficit, its hierarchical instability and its ever-shifting moral accommodations to the zeitgeist, and throws it all over for Rome. Though written with impressive erudition and humour, An Immovable Feast is a bracing exercise in parting the mists of rosy obfuscation so as to discern necessary religious distinctions. One such moment of clarification arrives when Blanski stops regarding "religious mysteries" as fascinating uncertainties to be interpreted as he sees fit in favour of the Catholic priest/poet Gerard Manley Hopkins' conception of mysteries as "incomprehensible certainties"; as realities that must be taken into account even though full understanding eludes us. In a similar way, weekly volunteer work Blanski undertakes leading Protestant Bible study at a medium-security prison, brings him face to face with professed Christians who have sinned so conspicuously that they've been locked up. Of course, everybody falls short of the glory of God but so wide a gap between aspiration and performance among those who have been born again, suggests to Blanski that there's something to be said for that cleansing office which the Catholics call Purgatory. And while Blanski plugs away leading his incarcerated crew through their study (each of the men reading from a different Bible translation) a Catholic priest breezes in and not only oversees Bible Study for his flock, he hears their confessions and offers up Holy Mass. Through a sequence of crystalizing instances such as this, Blanksi comes to understand which church sees the world for what it really is and does the most to equip her people to safely and fruitfully make their way through it. And though it costs him the prospect to ever serve as a priest, he and his wife move as they must and receive the sacraments of Catholic initiation on the same June morning as their baby son is baptized.  SOHRAB AHMARI SOHRAB AHMARI And finally we come to the book which asks all those big daunting questions that our resolutely dissolute age would just as soon ignore, Sohrab Ahmari’s The Unbroken Thread: Discovering the Wisdom of Tradition in an Age of Chaos (2021). Currently serving as the op-ed editor of the New York Post – the single bravest daily newspaper in the United States today – Ahmari was born in Iran in 1985 and came to America with his family at the age of thirteen. Like Tyler Blanski, the prospect of fathering a child powerfully inspired Ahmari to clean up his act and get focused on what he really believed and what he wanted to hand on to his children and three years ago he joined the Roman Catholic Church. (His conversion story, From Fire By Water: My Journey to the Catholic Faith was published two years ago and is due to arrive in my in tray imminently; that's how impressed I am with this book.) When that child was born Ahmari named him after Maximilian Kolbe, a Polish priest (declared a saint in 1982) who was martyred in Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1941. The goons in charge of that camp had selected ten inmates to execute in recompense for an escapee from Kolbe's block. The ten had been selected and Kolbe was not one of them but he volunteered to be executed in the place of another inmate whose wife and children were with him in that Nazi hellhole and had urgent need of him. I venerate Kolbe's selfless act of sacrifice and courage but I must admit that I flinched a little when I learned that Ahmari had hung that name with those associations around the neck of a newborn baby. That instinctive reaction puzzled me. After all, Catholics have been naming their children after martyred saints whose ends were just as grisly as Kolbe's for two millennia. Was it just because this martyrdom feels so close to us in time that it gave me pause? Or because anything associated with the Nazis still retains such a bite? Clearly, Ahmari has no such qualms about heavily freighted nomenclature. "Kolbe," he writes in The Unbroken Thread, "climbed the very summit of human freedom. He climbed it - and this is the key to his story, I think - by binding himself to the Cross, by denying and overcoming with intense spiritual resolve, his natural instinct to survive: His apparent surrender became his triumph. And nailed to the Cross, he told his captors, in effect, I'm freer than you.. In that time and place of radical evil, in that pitch-black void of inhumanity, Kolbe asserted his moral freedom and radiated what it means to be fully human." Ahmari is convinced that no good is served when we dial back our proclamations of what is honourable or true out of aesthetic considerations. Nor does he see any good when we muffle our criticisms of worrying trends or developments because we don't want to call attention to ourselves or appear un-progressive or ungrateful. Writing as an immigrant from a country whose freedoms and best traditions were traduced by theocratic thugs, Ahmari cherishes the liberty and opportunities that prevail (for the moment) in the West. But he can't help noticing how many of those liberties are only geared to "maximizing individual rights and ensuring the smooth functioning of a market economy" and enshrine "very few substantive ideals" that inculcate the best qualities in our community or our children. “A radically assimilated immigrant isn’t supposed to complain about his freedom," Ahmari writes. "Yet as I grow into my faith and my role as a father, I tremble over the prospect of my son’s growing up in an order that doesn’t erect any barriers against individual appetites and, if anything, goes out of its way to demolish existing barriers . . . What kind of a man will contemporary Western culture chisel out of my son? Which substantive ideals should I pass on to him, against the overwhelming cynicism of our age?” And it is that Christian and fatherly concern about a social order that disregards the good and the true which has inspired Ahmari's twelve big questions; six of them addressing The Things of God and six of them addressing The Things of Humankind. Each of the chapter-long discussions focuses on a historical figure - some famous, some quite obscure; some ancient, some fairly recent, some traditionalists, some reformers - who notably grappled with the subject in question during their lifetime. Some of the questions pertain to hot-button issues of our day - for instance, What Do You Owe Your Body? touches on the unprecedented mania for corporeal butchery in the transgender community - but those discussions take in a much longer time-frame than is usually examined and feature minimal input from the bores and propagandists who routinely hog all the microphones today. I was delighted to see Ahmari take on a discussion of the divinely mandated "day of rest", which we only did away with in the West about forty years ago, in Why Would God Want You To Take a Day Off? Ahmari builds this chapter around the campaign to preserve the tradition that was waged by New York Rabbi Abraham Herschel. It's amazing how completely our society seems to have forgotten that old injunction which had prevailed for literally thousands of years, And it's interesting to ponder the part which removing that regular day of reflection has almost certainly played in ratcheting up our levels of social frenzy to eleven. And the man also gets points for bravery in his discussion about pornography in Is Sex a Private Matter? by building that chapter around the most reviled feminist of them all (even other feminists hated her), Andrea Dworkin, who, for all her crankiness and off-the-charts paranoia, did deduce a thing or two about the desolating, coarsening damage that porn's proliferation has dumped upon us all. In The Unbroken Thread's brief conclusion, a two page Letter to Maximilian, Sohrab Ahmari dispenses a few final nuggets of wisdom to his son, including this proposition which I'll have no trouble implementing because it accords so completely with my usual proclivities: "To read old books before new ones." And when I do next cast about for new books to take up I will happily consider anything by Messrs. Klavan, Blanski or Ahmari.

1 Comment

Susan Cassan

29/7/2021 08:27:44 am

Thank you, Herman. Although, like all dedicated readers, my pile of books to read gets frighteningly higher daily, I am pleased to add new titles to that precarious pile. This list is a treasure trove. I M particularly interesting in the view from a man who is looking at our world slantwise from the outside. It is terrifying to see just how rapidly the erosion has undermined the edifice we depend on for shelter and protection. We not only have relentless enemies without, but determined destroyers within who are teaching our children that the utter destruction of the West is the only moral choice, and that the mutilation of their own bodies is the only adequate response to the guilt they bear for being born within it.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed