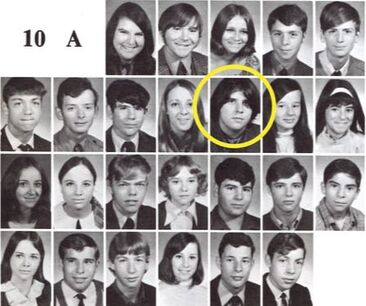

Darla Campbell (wearing glasses) with students Darla Campbell (wearing glasses) with students LONDON, ONTARIO – Although I never did earn my high school diploma and assured each of our kids when they were growing up that quitting school on their 16th birthdays was fine with me so long as there was some honourable study or pursuit to which they were prepared to commit themselves, I also have to admit that if it hadn’t been for a certain teacher of English, I might never have taken hold of my aptitude for writing and developed it into the primary vehicle by which I have experienced and interpreted my own life and the world around me. Before I met this teacher, I had been a notoriously indifferent and unengaged student who only really shone at recess. I had coasted through public school easily enough as so very little was required but was utterly unprepared to meet the more exacting standards of high school. After failing grade nine at South Collegiate Institute, I had been sent down river to rot in a four year business and commerce course at H.B. Beal. I did learn how to type there (which came in handy later) and was earning good grades in subjects so unnervingly simple that I frankly suspected it might be impossible to fail anything at that school. So I passed grade nine with flying colours and was sailing confidently through grade ten when it dawned on me early in the winter term that absolutely anything – even nothing – would have to be better than this terminally boring universe of invoices, receipts and computer index cards, and I quit school for the first time. I washed dishes for a few months at the recently opened Swiss Chalet on Dundas Street which was no duller and certainly more profitable than studying business and commerce. I packed that job in with the coming of spring and commenced keeping weird hours, growing my hair and earning pocket money by becoming a part time gardener to about a half dozen widows who lived in our neighbourhood. With the free time and the solitude which this regimen provided, I started to dabble in painting and writing – mostly hackneyed and pretentious poems at first. The painting even I knew was terrible. The poetry was pretty dreadful too but luckily for me, I didn’t know this at the time and was sufficiently intrigued by the material that was spilling out of me to keep writing and even to re-enroll at South in their four-year arts program where I knew there would be some emphasis on composition in my English course. So there I was, 17 years old and repeating grade ten – about as unmotivated and undirected as it was possible for one floundering kid to be. I wasn't proud to find myself in such a sorry state but neither was I embarrassed or ashamed. Indeed, I was aware of at least one salutary change in my attitude which had been effected by quitting school. I would be attending now on my own terms and was ready to seriously consider a word of real encouragement or challenge from any teacher who’d actually make the effort to try to figure out what made me tick. Though I still didn’t give a toss about a diploma or a well-balanced smorgasbord of courses to study, I was finally willing to throw myself into the right kind of work if it should become clear what that was. If I’d been faced with the usual scholastic craperoo at this particular juncture – another round of bored and tired teachers pounding irrelevant data into the heads of reluctant students – it would have been dead easy for me to quit again and give up that game for good. My English teacher, Darla Campbell, was a barely seasoned rookie, beginning her second year. Only five years older than me, this seemed a big enough gap for me to classify her as an adult but not as an alien. What she may have lacked in experience and erudition was more than compensated by a forthrightness and a curiosity such as I’d never encountered in a teacher before. Sensitive enough to twig to the loneliness and fear of the pathologically shy, she had ways of drawing them out. At the same time she had the kind of courage and sincerity which could stare down the bully or the snob and melt some of their belligerence away; at least for the duration of her class. I handed in a poem that first week in September – a rambling, doggerel epic about the agonies of being fat – and the next day Darla asked me to stay after class. A private meeting? She couldn't deliver any sort of verdict in front of other people? I was as nervous as Pavlov’s dog. Past experience suggested that this could mean only one of two disagreeable things; she was either going to reject the piece outright as being an unsuitable theme for poetic exploration, or else she was going to suggest a series of meetings with the school psychologist so we could constructively discuss my little problem. Bless her heart, she resorted to neither of those anticipated responses. “I can’t mark this,” she said and dropped the pages onto my desk. “There’s no way. But I enjoyed reading it and I’ll read anything else you can bring me. Do you need me to tell you that you write very well?” Yes, I nodded that I needed to hear that. “You write very well and I hope you’ll do a lot more.” And so I did. I’ve kept the 200-page folder of compositions I cranked out that year and most of it is paralyzingly awful. About all I can say for the literary abilities of the addled twerp who was me in the 1969–70 academic year is that he certainly was an enthusiastic young fellow and he was never guilty of understatement. But if I discard today’s more objective, critical self-analysis and remember that year as it felt at the time, then I recall an experience of awakening as intensely fulfilling and transforming as first love. Prior to that year, I didn’t have a clue what I was going to be when and if I grew up. In the wake of that year, I had no choice. I was going to be a writer.  And Darla worked similar miracles with a lot of the kids in that class. We were in 10A that year. In previous years, kids in the four-year course were assigned to 10E or 10F. In a transparent ploy to throw off any stigmatization that might accompany such alphabetical ranking, four-year classes were now being given the ‘A’ suffix. It didn’t work. Everybody still assumed that four-year kids were the same assortment of misfits headed straight for the social scrapheap. We were flunkies and dropouts; the kind of kids who’d wear slippers to school in January; kids who had to take medication and meet with probation officers twice a week. South at that time had pretensions as a school of academic distinction and had a reputation for snobbery second only to Central’s. Other teachers could be witheringly condescending to four-year kids but Darla – her heart ever aligned with the underdog – clearly liked us the best and went to bat for us again and again. Nobody from our class would be hitting up daddy for $800 so we could accompany the school band on its triumphal tour of the concert halls of Europe. So Darla made sure that we got a field trip of our very own (which simply wasn’t done with four-year students) and took us all down to Toronto on the train for a visit to the Royal Ontario Museum and to the movies – Stanley Kubrick’s production of Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey which we’d been reading in class. English was the final class of the day for 10A which was probably the best way to arrange things. It gave us something to live for. No matter what kind of guff and abuse we’d had to put up with from 9:00 a.m. to 2:15, our day would be rounded off with a session in the company of a teacher who never talked down to us or through us but knew how to talk with us; as individual human beings from whom great things could be expected. When we learned that June that Darla would be temporarily hanging up her chalk to spend a year in England, the class threw her a party at my place and then she turned around and threw a party for us at her parents’ cottage in Grand Bend’s Southcott Pines. At the end of the school year Darla announced that I was forbidden forthwith to address her any longer as "Miss Campbell"; an adaptation which I initially found unnatural and even a little indecent. But, as the I Ching says, "perseverance furthers." The adjustment soon lost its unsettling novelty and - as Darla knew it would - the shift in nomenclature acknowledged a more equal status in the way we related to one another. When Darla took up residence in an Earls Court flat that fall, I started inundating her with onion-skinned letters and stories through the mail. Then the great Canadian postal strike of 1970-71 left us incommunicado for a few months. This apparent calamity also turned out to be a most propitious gift. Now, instead of firing off each new work of genius two minutes after finishing a hasty first draft, I started revising, polishing and stockpiling my work and tackling longer projects. In short, I started taking the challenges of the writing life more seriously. By the time that strike concluded, I had hand-written a rather hefty autobiography and was well on my way to compiling my first typewritten collection of short stories . Darla came back to Canada and started teaching in Toronto. I visited her there a couple of times and we usually managed to meet when she was in London or I’d hitchhike up to the Bend to see her in the summer. In the last week of August, 1971, I took up residence there when her father hired me to paint their cottage. But the world we had shared was coming unraveled and our opportunities for getting together were fewer. Truth be told, I had been more than a little besotted with her and was very reluctant to let our time together slide away. But when I heard from her mother that she was engaged to marry another teacher – a Phys. Ed. teacher, for God’s sake – even I knew that the time had come to put away childish things and get on with real life. In my 39th year I decided to get a head start on my mid-life crisis and in reviewing my life’s milestones and turning points, I was thinking about her a lot. I thought I might try to track her down if she still lived somewhere in greater metropolitan Toronto but my sleuthing turned up a mailing address in Bedford, Nova Scotia so, as usual, I inflicted my presence upon her via the written word, mailing her off a small carton of books and articles and a letter. The letter was newsy and chatty enough but at its heart was an expression of deep gratitude for helping me find my way. In responding to the letter, she denied, as usual, that she’d ever been able to teach me anything; insisting that I was one of the great "unteachables" who only need to be encouraged to bring forth the gifts that are theirs to be developed. Which might be true enough but it still takes a special kind of teacher to do that. So far, I know of two: Socrates and Darla Campbell. Photos taken from the London South Collegiate Institute yearbook, Acta Meridiana 1970

4 Comments

SUSAN CASSAN

11/11/2019 11:03:54 am

How wonderful to (re) read this heartfelt tribute to your teacher. It brings back a time in education when honesty and authenticity was valued and foolishness could be laughed at. I do not know where, today, a young person can find that kind of education. When a student is excoriated for defending the traditional red poppy vs the "rainbow poppy", what have schools become? Perhaps, still, there are students who meet the right teacher at the right time, and connect with what will become their life's work and passion. I suspect that Emily will be that teacher for many a student. That's what gives me hope when I become discouraged at what has become of the profession I loved.

Reply

Randy Fisher

12/11/2019 03:50:33 am

"Truth be told, I had been more than a little besotted with her and was very reluctant to let our time together slide away."

Reply

Max Lucchesi

13/11/2019 11:10:33 am

Brilliant piece Herman. Like you I was lucky, during my school days I met 3 wonderful teachers who in their different ways helped a shy young Italian boy find his way and managed to instill in him a love for history and literature. Those teachers still exist and are still helping their pupils extend or find themselves, I know from the parent/teacher evenings and the respect my own boys held for certain of theirs. In all professions as in all walks of life there is gold among the dross. Again from those same evenings too many parents whose children 'do no wrong' would carp and complain. Blaming the school for their own lack of parenting and in their ignorance lump the gold with the dross. Holden, running away from school meets the mother of a classmate who describes her son as sensitive. As sensitive as a goddamn lavatory seat is his inward reaction. Aint that the truth.

Reply

Dennis Klinck

4/12/2020 03:02:31 pm

Dear Herman,

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed