LONDON, ONTARIO – My good friend Vince Cherniak will be familiar to many of you from his two-year stint as in-house art critic for The London Yodeller which I edited from 2013 to 2016. In addition to his regular Look at This column, Vince was also a frequent supplier of our Yodeller Interviews where his usual modus operandi was to plop two to three times more material than we could possibly publish into my lap with a request to pare it down into usable form. Well, Vince is now working away at his family memoirs and in a shamelessly ingenious ruse to save himself some labour, he has decided to outsource some of the writing for this project to other people. One major theme of Vince’s life story is his amazement that he still lives in the same house that he grew up in on Forward Ave. He’s not sure that he ever meant to do this. Indeed, he’s still not sure that he really likes it here in London and wonders if his lifelong but unintentional commitment to this place makes him, not just a regionalist, but a hyper-regionalist. I’ve delayed fulfilling Vince’s writing assignment for the better part of a year; partly because he’s asked me to be concise and I’m not sure that I know how to do that on a subject so tangled up with my own deepest thoughts about identity, perception and inspiration, and also because I’ve selfishly wondered, ‘What’s in it for me?’ But since starting up this blog last month, it has occurred to me that I could pull a fiendishly reciprocal switcheroo here and not only outsource some of the work on my blog to Vince but also let him edit me for a change as he determines what, if anything that I have to say on this subject is fit to his purpose in writing his book. So without further ado, here is Vince’s original preamble and challenge to me:

And greetings to you, Vince.

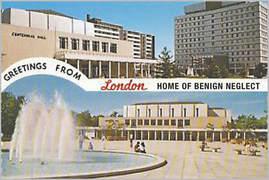

I suppose we should open with a note making clear that the Souwesto brand of Regionalism which took flight in the 1960s, spearheaded by Greg Curnoe, was categorically distinct from the American movement of that name in the 1930s and early ‘40s which was associated with such artists as Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton and Andrew Wyeth. The big drive with the American Regionalists was to record and frequently celebrate in defiantly non-abstract ways an older and less urbanized way of American life. For Curnoe there was no rejection of abstraction and other nontraditional approaches to artmaking; no nostalgic look back at a less hurried time. The key principle was a repudiation of Toronto or Montreal or New York as arbiters of what was worthwhile art; a casting away of the then-reigning premise that one had to win some sort of seal of approval from curators or critics in these larger and better connected centres before any sort of career in art could credibly proceed. Considering the talent, commitment and fierce independence required to pull off what these men were able to accomplish, I would take issue with the passivity of your statement, “So it just happened to work out fine” for the London, Ontario regionalists. Curnoe saw no deprivation (indeed, there were many benefits) to living and working in a place that might be perceived as a cultural backwater. He believed that wherever an artist happened to live was fine; that in fact there was probably more potential for a really original vision to flourish away from the usual centres. In Nowheresville an artist was less likely to get caught up in passing fads and sensations and would be better able to shut out any distracting media buzz and instead zero in on the forces in his own life and immediate environment that most fascinated him. In a 1970 interview with Elizabeth Dingman of The Telegram, Curnoe answered the mandatory ‘So why do you insist on living in boring old London?’ question this way: “It’s where I was born, where my sons and many of my friends were born. What goes on here couldn’t happen in cities over 200,000. In a small city there is less privacy but more concern with people. That’s how things get done. People know what you are doing. It gets around pretty quickly. There is none of the closed-up studio paranoia of ‘I’ll not let the guy in because he’ll steal my ideas’ . . . I don’t want London to change too much. Probably I’m pro-Canadian because I think the only way you can progress is in a small situation. The same holds true for Ontario, for Canada. There must be resistance to the U.S. which is a centralizing force geared to commercial interests. There’s nothing in that setup for anybody. I’d rather be called anti-American than pro-Canadian. “I’m not talking about isolation. At one time nobody showed outside London, but you can’t sell enough here. You have to have it both ways, otherwise you get a narrow thing. You cannot afford to ignore what’s going on outside but you must not lose sight of what’s first: the things within hearing and seeing distance. That’s where it all starts. That’s where I think McLuhan is incorrect in his assumption of the world as a village. Our culture is extremely complicated. The only one we can possibly understand is what we come in immediate contact with . . . There is a distinct culture here as there is in regions all over Canada. It just needs articulate artists to bring it out.” A big Curnoe watercolour which I saw during a studio visit in 1988 (never finished or titled and presently rolled up in a tube at his Weston Street home) featured a pair of sunglasses, a guidebook and a touristy t-shirt floating in the air over Lake Huron. On the front of the shirt were printed four place names of international importance – London, Paris, Rome and Grand Bend. The Bend, of course, is London’s beach playground on Lake Huron, 40 miles to the north. But Curnoe being Curnoe, London - and for that matter, perhaps Paris as well - were winking references to the Ontario cities that bear those names. Yes, it was a joke but yes (as with most of Curnoe’s jokes), on some significant level he meant it too. Curnoe believed that the operational factor in art and life is the consciousness of the perceiver: that anywhere on planet Earth could serve quite nicely as the gateway to experience and truth so long as the artist had an organic connection to that place. Jack Chambers’ early attitude towards London more closely matches your own. Feeling hemmed in by what he experienced as “utilitarian” and “puritanical” pressures to secure “a safe job” and “a proper living” in this “indifferent” town, he made a run for it at the age of 22. Chambers thought he needed classical training to equip himself to master any project and painstakingly crossed an ocean and gave up almost a decade of his life to acquire such skills, primarily at the Escuela Central de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid, Spain. He then discovered that while he had the techniques down cold, he had cut himself off from his own wells of inspiration. He could paint classically but he couldn’t conceive or be inspired classically. For that he really did have to come back to the city and the people he’d jettisoned a decade before. A couple of years after returning to Canada, Chambers told the Toronto Star’s David Cobb that maybe there was a sort of artistic birthright that could only be tapped into in the place where an artist was born: “I’m interested in building up an alphabet of my own . . . in a realistic way that doesn’t go back to the old stuff of a few years ago . . . Spain’s a country with a golden age of art, a full breast to draw on . . . It was one of the things I envied most about their painters today, this continuous flow of tradition behind them all, and I think the best new realistic painting will come out of Spain . . . You’re suckled off your own I suppose . . . If I’d been born in Spain, I might have been able to do it justice. I’d have felt it belonged to me. As it was, in that clear landscape with its browns and greys, I was a stranger and forever in a vast hurry.” In an autobiographical account of his return to Canada, Chambers writes of his quickening sense that maybe London was where he was supposed to be after all: “I had returned to Canada via New York, and took the N.Y. Central railway to St. Thomas and then a cab to London. It was while riding a city bus uptown that its slow smooth ride spoke to me of opportunity and comforts I could not expect in Spain. It was a feel for the place that produced my intention to stay on in London. It was also my home town, and there were spaces here along the river and in the landscape that had become mine years ago and continued to be so. The memory of such places multiplied the longer I remained so near them, and the images wedded to their presence surfaced in me like the faces of long lost friends. At this time, I discovered my own past, that of my parents and of their parents, in the likenesses preserved by photographic magic. I dug up all the photos I could find from both the McIntyre and Chambers sides of the family. I was to use these photos soon in my paintings.” Long before I’d met or had any real appreciation what any of the London regionalists were up to, Greg Curnoe became, just by the fact of his existence, an inspiring figure to me. In the opening paragraphs of my portrait of Curnoe in Three Artists: Kurelek, Chambers & Curnoe, I recount his dawning on my consciousness” My oldest brother Dave was tooling around in our parents’ car one autumn night in the mid ‘60s when he drove down Weston Street and pointed out a rather boxy and flat-roofed house to me. “That’s where Greg Curnoe lives,’ he said. “It used to be a factory.” “Who’s Greg Curnoe?” I asked in my ignorance which was profoundly deep and total. I would have been 14 or 15 years old. “He’s an artist,” said Dave, and a whole series of cosmic tumblers fell into place in my skull and the universe suddenly became more interesting. This was the first time I’d heard of an artist who wasn’t dead or who didn’t live so far away that I’d probably never get to see his house. The implications of this were staggering. “It can happen here,” I thought. “It can happen now.” One definite difference in our approaches to this burg where we both seem destined to play out our lives, is that I actually like it here and always have. Of supreme importance to me (I don’t expect its significance to impinge much on anyone else) is the fact that I was born here. All of my earliest impressions and understandings were forged here. Clearly, it’s more a matter of temperament than geography. Some people can’t wait to shake the dust of their old hometown off their feet. I’ve never been constituted that way. As a teenager first reading the life stories of the Brontes, I identified like crazy with the heartache they endured whenever they had to leave Haworth, England for an extended period of time. There are dear landscapes and streetscapes and a hundred other locations in London that are nourishing for me to visit or just gaze upon; administering a blast of revitalizing water that seeps through to the very deepest of my life’s roots. Growing up I’d hear all the usual grousing about how dead the town was, how there was nothing to do on weekends and London was some kind of cultural desert and the city fathers and mothers were all such unimaginative frumps . . . and I was so wrapped up in what I was doing with my friends and my brothers and digging into the little musical and literary explorations I had going on the side . . . that their complaints meant less than nothing to me. I’ve never relied on theatres or museums or concert halls to determine the extent of my engagement with London. I’ve never expected my municipal leaders to embody or represent my particular interests. I just want them to put up the lights in Victoria Park every Christmas and otherwise leave me to my own devices. I profoundly appreciate the fact that it’s always been cheaper to live here and am certain that was a matter of some salience in giving rise to our regionalist movement. With a bit of self-management, this is a town where any aspiring artist can carve out the time and the psychic space to take their own ideas for a walk and see what develops. At about the same age as you when you hauled your sorry ass back here from Germany and wondered why you’d bothered to return, I returned from the obligatory 20 year-old Londoner’s trek to Vancouver and, though nursing a broken heart, knew I was back in the only place where I felt like me. This early passage from the novel I wrote that year, The Goof, captures some aspects of that sense of belonging which has always made it impossible for me to consider living anywhere else: It was shortly after Irene got back from Halifax that we started the search for the Hendersons, the quintessential London household. I don’t believe I would’ve known what to look for before. The prominent smell on their street is trees, lovely fat old trees, shading and covering the street with keys and leaves and chipped bark for most of the year, collecting snow in the nicest possible way during the off season. The Hendersons live in a large two-storey house which borrows shamelessly from the Victorian era in design. The lawn is immaculate, evenly grown and coloured a deep enough green to compete with seaweed. People respect the Hendersons for this. The postman always uses their sidewalk and the paperboy, fearful of throwing off the wondrous symmetry of it all, uses a ruler and compass when placing The London Free Press on their doorstep. The Hendersons are good churchgoers and quite arrogant when it comes to choosing their friends. If you weren’t born here, forget it. Won’t give you a chance. They have money to burn but they don’t. Needless to say, they vote Conservative. It is Sunday afternoon in July, quite warm, and the Hendersons are packing up their car. A beach ball, some towels, baseball equipment and a huge thermos full of orange Kool-Aid made by Mrs. Henderson, complete with orange and lemon peelings. The car is a 1970 Pontiac Parisienne. Mr. Henderson washed it earlier this morning. It is a four door sedan, dark blue in colour, a modest amount of chrome, no ornaments. The Hendersons have three children. Young. Their gender and names are unimportant. It is more important that we not really know them. “Goin’ to the beach, eh?”asks shirtless Mr. Lewis from next door as he hoses down his freshly seeded lawn. Mr. Lewis’ question was not necessary. Mr. Henderson now walking over to him knows this and Mr. Lewis knows it too. Neither of them lets on. “Yeah, thought we’d take the kids up to the Bend. New seed taking root yet?” Mr. Henderson’s question was not necessary. The score is even now. They have been next door neighbours for six years. Mrs. Henderson and the kids are all in the car now. They would like to leave. “It sure has,” says Mr. Lewis. “That seeder of yours really did the trick. Oh, I haven’t returned it yet. Just put it in your garage, will I?” “Yeh, that’ll be fine. If you can find any room in there.” Mr. Henderson laughs at his little joke. Mr. Lewis isn’t too sure that a joke has happened. He thinks maybe it’s his shorts. “Yeh, sure,” says Mr. Lewis. “Daddy, hurry up,” says a genderless Henderson child. “Hush,” says Mrs. Henderson. “Slave-drivers,” quips Mr. Henderson. Mrs. Henderson blushes. Mr. Lewis laughs. “Here we go, then,” says Mr. Henderson, getting into the driver’s seat. “It’s about time,” says a genderless Henderson child. “Roarsey, roarsey,” says the motor. And the blue Pontiac Parisienne pulls out of the laneway into the street and heads north for the Bend. Mr. Lewis watches after, waving goodbye to his neighbours the Hendersons. Once the car is out of sight, he bends forward and washes his head with the hose. I would just point out that in that passage, there is a more than passing acknowledgement – indeed there is a kind of celebration – of the banality and cultural narrowness that typified London at that time. And, of course, banality and narrowness still exist today, in perhaps more suffocating profusion than ever, though the ways in which they tyrannize us have changed. And that’s the other great thing London has always supplied in abundance – lots of maddening aggro to kick against – which I have always found very clarifying in showing me who I am and where I stand.

4 Comments

Barry Wells

6/2/2018 02:43:51 pm

Few know it, but one of the best places to live in the world is Otterville, Ontario ~ about 20 miles north of Lake Erie in Norwich Township in Oxford County.

Reply

Brenda Strand

14/2/2018 09:41:30 am

Very interesting Barry. I know there's a grid system that when laid over the planet can be used with ones DOB to find coordinates for the best places energetically on the planet for an individual to live; where they would find the most happiness, peace and success. Possibly these myocardial hypertrophic regionalists are in there 'good coordinates' on the planet. This grid has been a bit elusive for me to find though.

Reply

Vincent Cherniak

7/2/2018 01:36:11 pm

Your line about having little expectation of the municipality and its leaders — other than to put up the Christmas lights in Victoria Park, and otherwise leave me to my own devices — is a very good one. I’m pretty much in full accord.

Reply

Vincent Cherniak

7/2/2018 01:44:43 pm

RE: Otterville

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed