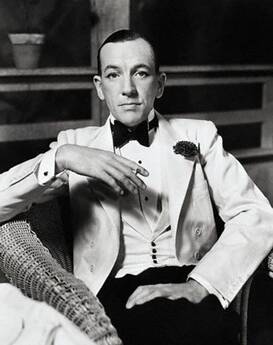

NOEL COWARD (1899–1973) NOEL COWARD (1899–1973) LONDON, ONTARIO – Most years I can expect to endure one cold, usually in January, and about once a decade I will host a flu bug for about a week. While I don’t exactly enjoy these feverish bouts of downtime, they do have their compensations. Aching muscles and protracted coughing fits are a drag but it’s always a treat to be able to book a few days off and devote what energies remain to nothing more productive than reading and watching old movies. And the timing of my annual cold is perfect for tackling that stack of books and DVDs I’ve invariably received for Christmas a few weeks before. Those same diversions also see me through the flu but with that particular bug there is the added attraction of vomiting. Once again, it would be a lie to say I enjoyed it, but as this weird paroxysm has only taken hold of me six or seven times in my earthly existence, I’m still rather fascinated by what happens when one’s entire digestive system flips into a violent reverse gear. Down on my knees in nausea’s clammy-fingered grip and hugging the cold white porcelain throne in anticipation of the next eruption, some part of me is still able to watch in utter astonishment and exclaim, “How fearfully and wonderfully made am I.” Eleven year-old Gracie was little more than a pup when I had my last flu rendezvous. I like to think we had our primary bonding experience when I pressed her into companionable service as a four legged hot water bottle as I had myself a Noel Coward (1899–1973) book and movie festival. That was when I read for the first time Graham Payn and Sheridan Morley’s wonderfully chatty 1982 selection from The Diaries of Noel Coward, and that prompted me in turn to revisit favourite scenes (in book and filmic forms) from several of Coward’s plays. I emerged from that Cowardian saturation marvelling once again at the stinginess with which the academic establishment insists on underrating Coward’s work. In addition to writing tremendously popular plays and songs, Coward also starred in those plays and sang those songs. “A star is his own greatest invention,” John Lahr writes in his introduction to his insightful study of Coward the Playwright. “And Coward’s plays and songs were primarily vehicles to launch his elegant persona on the world.” Routinely speaking and singing in what Lahr describes as a “clipped, bright and confident style which irresistibly combined reserve and high camp,” the main focus was always on Coward the entertainment phenomenon rather than his remarkable strengths as a writer and composer. I expect this was particularly the case in his youthful prime when his image was everywhere and he was regarded by armies of adoring fans as the very brightest of the bright young things. But even when he was well into his fifties and his prominence and cache had considerably retracted, that undervaluing continued. Without bitterness, Coward himself acknowledged as much in a 1956 diary entry: “I think on the whole I am a better writer than I am given credit for being. It is fairly natural that my writing should be appreciated casually, because my personality, performances, music and legend get in the way. Someday, I suspect, when Jesus has definitely got me for a sunbeam, my works may be adequately assessed.” Well, that more generous day of reckoning is not here yet. In a reference book such as The Cambridge Guide to World Theatre, for instance, Coward’s incredibly prolific lifetime output (which included some sixty produced plays, more than three hundred songs, and at least a dozen other volumes of memoirs, screenplays, short stories, novels and posthumously collected diaries and letters) is dispatched with a miserly 135 words. And many of those words – “precious but witty,” “successful in their time but somewhat excessive in retrospect” – are frankly dismissive and even contemptuous. Setting aside his now rarely produced musicals, I would say that in the best of his narrative plays such as Blithe Spirit, Private Lives, Hay Fever, Present Laughter, Easy Virtue, and Design for Living, Coward is a master at portraying some of the furious ambiguities of romantic and familial life. I also hold in similarly high regard the screen adaptations, directed by the great David Lean, of earlier Coward stage scripts such as Brief Encounter and This Happy Breed. With crisp wit, a beautifully tuned ear for dialogue and an unerring gift for sketching distinctively conflicted characters, Coward shows how elusive stability and happiness can be in modern primary relationships; how we move mountains to attain constant contact with our beloved and then immediately start looking for ways to escape. There’s a comically neurotic paradox that Coward explores again and again in his tales. It seems that we no sooner fulfil our desire to love and be deeply known by another, than we start to become exasperated at the apparent predictability of the other person. That exasperation, of course, can be a two-way street as we start to chafe in turn at the restrictions and assumptions that the other person’s knowledge of ourselves seems to impose on us.  OSCAR WILDE (1854 - 1900) OSCAR WILDE (1854 - 1900) In that same edition of the Cambridge Guide to World Theatre, the currently over-celebrated Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) nets five times more words – virtually all of them complimentary - for a lifetime’s theatrical output of about one tenth that of Coward’s. What gives here? The only one of Wilde’s plays which is universally regarded as a classic is his last, The Importance of Being Earnest. In its dazzling display of epigrammatic virtuosity, Earnest is a heroically sustained frolic of polished witticisms lampooning the proprieties and conventions of class. Wilde creates a topsy-turvy, funhouse reflection of the upper crust Victorian world worthy of W.S. Gilbert or even Edward Lear. But over the play’s three long acts (in Stratford to mark the centenary of Wilde’s death, I saw their interminable four act version) a kind of frantic fatigue sets in. Like eating a sumptuously prepared dinner comprised of course after course of nothing more substantial than frothy meringues, by play’s end one’s mind, one’s intellectual molars, are practically throbbing for something meaty to bite into. How to explain the disparity of critical reputation for this pair of hugely popular playwrights? I believe it all has a lot more to do with modern sexual politics than what either of them actually wrote. While it so happens that both writers were homosexuals, because of his wretchedly mishandled private life and the ruinous opprobrium that it called down upon his head, Wilde is the golden boy, the sacrificial victim and poster boy, for gay rights. Coward was born 11 months before Wilde’s death in Paris where he’d been inexorably wasting away following two years’ brutal, spirit-breaking incarceration at Reading Gaol. So widely known was the scandal of his downfall, I expect that Wilde provided Coward with a cautionary lesson in conducting your private life in such a way that it never captured public notice. Wilde’s jail term had been brought about by a disastrous series of trials which he foolishly instigated against the unhinged father of Wilde’s young male lover, Lord Alfred Douglas. Goaded on by the vain and feckless Douglas whose hatred of his father was positively Oedipal, Wilde recklessly initiated the first court action, suing the Marquess of Queensberry for libel when he had spitefully (but accurately) identified Wilde in public as a sodomite – which the Marquess had spelled “somdomite.” In addition to Douglas’ prodding, Wilde’s grandson, Merlin Holland also speculates that Wilde had a “supreme and misplaced self-confidence that ‘society’, worshipping his talent, would never harm him.” You could hardly say the Marquess had ‘outed’ Wilde. His homosexual excursions with Douglas and numerous others were, his grandson says, “an open secret”, as was the quiet humiliation of Wilde’s largely discarded wife and two sons. His seedy reputation and his outrageous persona, his foppish wardrobe and his waspish quips were all components of Wilde’s naughty appeal to the bourgeois audiences he affected to disdain. Today, of course, far more entertainers in every field capitalize on the fact that a good sized audience can be amassed for entertainers who thumb their nose at commonly held proprieties. But it was a novel trick in 1895 and it suddenly stopped working - and public opinion took a swift and tidal turn against him – once the sordid details were dragged out in court. When his own cross-examination started to go badly at that trial, Wilde decided to withdraw his prosecution in a bid to shut the process down even though this meant that the Marquess was thereby acquitted and Wilde got stuck with mountainous legal expenses which effectively bankrupted him. If he thought that would be the end of it, Wilde was naïve. Even before he left the courthouse, the Crown was applying for a warrant for his arrest on charges of sodomy and gross indecency. It would take a couple of days to obtain and serve Wilde with that warrant and it was understood by Wilde’s counsel and his truest friends, like Robbie Ross, that if he quickly caught a ride across the channel to France and never came back to the UK, he would never have to face this particularly unpleasant music. But instead, he dawdled in London for two days where he was arrested in Room 118 of the Cadogan Hotel on April 6th of 1895. Many people have speculated whether it was honour, pride, some kind of death wish or just disbelief that things could possibly be this bad that impelled him to resist making his escape. I find John Betjeman’s 1937 poem, The Arrest of Oscar Wilde at the Cadogan Hotel, to be one of the likelier explorations of his vain and fidgety state of mind: He sipped at a weak hock and seltzer As he gazed at the London skies Through the Nottingham lace of the curtains Or was it his bees-winged eyes? To the right and before him Pont Street Did tower in her new built red, As hard as the morning gaslight That shone on his unmade bed, “I want some more hock in my seltzer, And Robbie, please give me your hand -- Is this the end or beginning? How can I understand? “So you’ve brought me the latest Yellow Book: And Buchan has got in it now: Approval of what is approved of Is as false as a well-kept vow. “More hock, Robbie — where is the seltzer? Dear boy, pull again at the bell! They are all little better than cretins, Though this is the Cadogan Hotel. “One astrakhan coat is at Willis’s -- Another one’s at the Savoy: Do fetch my morocco portmanteau, And bring them on later, dear boy.” A thump, and a murmur of voices -- (“Oh why must they make such a din?”) As the door of the bedroom swung open And TWO PLAIN CLOTHES POLICEMEN came in: “Mr. Woilde, we ‘ave come for tew take yew Where felons and criminals dwell: We must ask yew tew leave with us quoietly For this is the Cadogan Hotel.” He rose, and he put down The Yellow Book. He staggered — and, terrible-eyed, He brushed past the plants on the staircase And was helped to a hansom outside.  Oscar Wilde with Lord Alfred Douglas Oscar Wilde with Lord Alfred Douglas In comparison to all that, Noel Coward’s was a charmed life. A child actor who never seems to have doubted for a second how he would make his way in life, he achieved success and the right kind of notoriety early on, acquiring his first Rolls Royce at the age of twenty-six, and being the subject of a full length biography in his early thirties. A mere three decades after Wilde’s downfall, the much more discreet - and much more consistently homosexual Coward (which is to say he never seems to have even considered romance with a woman, let alone marrying one and fathering children) – was hobnobbing with royalty and high society, not as a provocateur or aesthetic scold but as an equal and a friend. Coward was a favoured guest of the late Queen Mom (whom he adored in return) and a good friend of Winston Churchill’s. When the tide of the Second World War finally turned Britain’s way, Coward was brought to Chequers specifically so he could teach the Prime Minister how to play his new song, Don’t Let’s Be Beastly to The Germans. And the two of them sat together at the piano pounding out this wickedly funny song, raucous tears of laughter streaming down both their faces. Don’t let’s be beastly to the Germans When our victory is ultimately won, It was just those nasty Nazis who persuaded them to fight And their Beethoven and Bach are really far worse than their bite, Let’s be meek to them – And turn the other cheek to them And try to bring out their latent sense of fun. Let’s give them full air parity – And treat the rats with charity, But don’t let’s be beastly to the Hun. Another song he wrote that month, London Pride, mined a completely different emotional vein, providing gentle solace and self-respect for his countrymen who had come through the Blitz and now were rolling up their sleeves to start the work of rebuilding. The chorus for this unashamedly patriotic song goes: London Pride has been handed down to us, London Pride is a flower that’s free. London Pride means our own dear town to us, And our pride it forever will be.  Noel Coward in middle age Noel Coward in middle age And another big vote in Coward’s favour for me is the fact that my late mother-in-law was a lifelong fan. Sheila Jarvis was thrilled in 1944 when she was stationed as a nurse in India and the great one – or ‘the Master’ as he ironically fashioned himself – turned up in her neck of the jungle to entertain the troops as part of a morale-boosting six-month tour that also took in the Middle East, South Africa, Burma and Ceylon. In her final few years when discreet funereal planning was not the furthest thing from our minds, we silently made notes when Sheila made mention of favourite poems and songs and hymns. And the one we put on her funeral card last March (how grateful we are that she slipped away a year before the Wuhan Batflu started wreaking havoc with proper memorial services) was this snippet which hails from we know not where in the vast Cowardian canon: When I have fears As Keats had fears, Of the moment I’ll cease To be; I console myself with Vanished years, Remembered laughter, Remembered tears And the peace of the Changing sea. For all of his pronounced talents and eccentricities, Coward was usually able to maintain a common touch. Yes, he was cognizant of his special gifts but he wasn’t squeamish about marshalling them in the service of universal stories or themes. His orientation may have set him apart from the vast majority of his fellow men but he wasn’t going to let that stop him from writing about love and friendship in a way that anybody could relate to. In his play Present Laughter, Coward appeared as Garry Essendine, an aging playwright, theatre impresario and fading matinee idol who is starting to feel the strain of generating all that magic for a living. Coward acknowledged that there were more than a few autobiographical touches in this play. And I’ve always assumed that this little speech of Essendine’s about sex was one of them: “I enjoy it for what it’s worth and fully intend to do so for as long as anybody’s interested and when the time comes that they’re not, I shall be perfectly content to settle down with an apple and a good book.” There’s no question Wilde suffered more but I’m unconvinced that made him the better writer or the wiser man. On the contrary, I am inclined to agree with Coward when he writes a quick journal entry in 1946: “Am reading more of Oscar Wilde. What a tiresome, affected sod.”

2 Comments

Max Lucchesi

5/5/2020 09:58:08 am

As usual an excellent piece on Coward, if a trifle one sided. I'm a fan of him too. His comic songs compare more than favourably with Tom Lerher or the Flanders and Swan Duo who were almost contemporaries with his later career. Have they all been forgotten also? His first and most serious play 'The Vortex' staged in 1924 is still being revived today and is as relevant now as it was then. Unfortunately most of his work Cavalcade, Blithe Spirit, Private Lives, This Happy Breed et al, while always worth a viewing, while beautifully written and hilarious, have had their day. I say this sympathetically as I would about the work of P.G. Wodehouse and Evelyn Waugh, again both of whom I love. But we are talking, no matter how many times we return to it, about a lost world. Of Oscar Wilde, I read his 'Happy Prince and Other Stories' as a child' and will never say a word against the man. But Herman, what surprises me is you compared Coward to Wilde rather than to William Somerset Maugham 1874-1965 his direct contemporary. Both with their first work achieved success at a relatively young age;Coward at 25, Maugham at 23. Both came from the same class, both were Homosexual, both with their work mirrored society and both in their travels worked for M.I.6, Both were prolific playwrights, authors, scriptwriters and today have been undervalued.

Reply

Sue Cassan

5/5/2020 11:31:29 am

Great article on Noel Coward. We have enjoyed his witty, wise, and elegant plays. I’m with you. He is much underrated. Somehow comedy, which can be profound, takes second place to anything solemn. Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest is a tour de force, but is closer to a juggler’s act of keeping more and more balls in the air than anything literary. I always feel bad criticizing it because it seems so mean to attack a joyous romp.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed