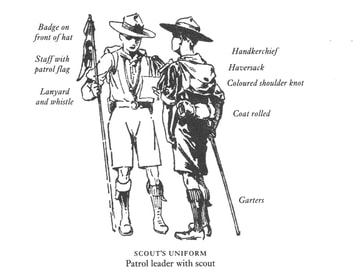

LONDON, ONTARIO – Like a lot of fellows, I exhibit minimal interest in matters sartorial. Sure, I can be fussy and stubborn about what I will and won’t wear. But I primarily dress for comfort and compared to the massive collections of books and recordings that I consider essential to a life worth living, my (if you’ll excuse the expression) ‘wardrobe’ is a pitiful and stunted thing. There is one suit and a couple of sports coats (donned for funerals and days when I give the readings at church) and otherwise I get by with three pairs of trousers, a half dozen shirts, two sweaters, a couple pairs of shoes, and a limited assortment (if that’s the right word when all of them are identical) of unmentionables. So how am I to account for the wanton extravagance of my much younger self who twice strained my parents’ bank account with my feverish demands to immediately acquire all the clothing and gear required for full membership, first in the Wolf Cubs and then the Boy Scouts? In actual fact, I did not give a toss about tying knots, starting fires without matches, or building suspension bridges out of locally sourced twigs and natural fibres.

My only interest was in the quasi-military uniforms – ungainly ensembles that would never otherwise have appealed to me, combining all-season shorts, knee high stockings, and silly hats. And I no sooner acquired these outfits than my enthusiasm in both associations went into free fall, followed within weeks by my official resignation. Twice my parents had to take out Want Ads in a pathetic bid to minimize their losses, seeking to unload the ‘almost like new’ uniforms that I had so recently and lavishly coveted. I remember that the green Cub sweater itched horribly but (other than general gorpiness) I had no such grounds for complaint with the Scout uniform. No, the main problem was that I found both these fraternities utterly baffling and boring and, truth be told, more than a little repellant. I couldn’t understand what some of my friends seemed to like about scouting, though none of them ultimately stayed with it for more than a couple of years. I had hoped that by getting myself fully kitted out in that way, some sort of transformation would be worked and I would magically crack the mystery, developing my own enthusiasm for a more outdoorsy and sporty life. And twice in a row – even though I acquired the uniform at ruinous expense – it did not happen. As a kid I was merely puzzled – and maybe a little disappointed in myself – by my contending attraction/revulsion to the weirdly unengaging world of scouting. Why couldn’t I get with this program that was commended by so many? But several decades later when the Oxford University Press reissued the original 1908 edition of Lord Robert Baden-Powell’s, Scouting for Boys, I read it in one greedy, revelatory go; marveling at what a grab bag of puerile, reactionary hooey it contained and congratulating myself for dodging this particular bullet. Though the manual we were issued in the ‘60s – Tenderfoot to Queen’s Scout – was a committee job produced by the National Council of the Boy Scouts in Ottawa, that reprint contained a lot of the same mumbo jumbo which used to strike me as so absurd. Go ahead, ask any ex-Scout: What, precisely, were you trying to express when you gathered around that campfire each week (ours was a phony, electric model with glowing red logs set up in the middle of Mountsfield Public School’s gymnasium floor) chanting, ‘Oon gon yamma, gon yamma, en vooboo, yabo, yabo, en vooboo. He is a lion. Yes, he is better than that. He is a hippopotamus. Dyb, dyb, dyb’? Okay, the ‘dybs’ I sort of get, being a short form iteration of one of the scouting mottos, ‘Do Your Best’. But the rest of it? Baden-Powell’s original manual – freely borrowing material from Rudyard Kipling’s Kim and Jungle Book stories, Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, Indian lore collected by Ernest Thompson Seton, Samuel Smiles’ Self Help, and his own reminiscences as a commander in the Boer War – was a bit of a committee job itself. Though the material is assembled and crammed together in an appallingly slipshod way, it is the blustery, bigoted, and overbearing persona of Baden-Powell himself that makes this document such compelling reading today. His stern warning about the “unmanly vice” of “self abuse” which “brings with it weakness of heart and head, and, if persisted in, idiocy and lunacy,” has rightly become infamous. In the appendix, editor, Elleke Boehmer, thoughtfully provides the even wilder original version which Baden-Powell’s publishers insisted he tone down: “A very large number of the lunatics in our asylums have made themselves ill by indulging in this vice although at one time they were sensible cheery boys like any one of you. The use of your parts is not to play with when you are a boy but to enable you to get children when you are grown up and married. But if you misuse them while young you will not be able to use them when you are a man: they will not work then.” Racial and social stereotyping as well as the most callow, chest-thumping imperialism suddenly erupt in section after section, even when they bear no possible pertinence to the subject under discussion. Perhaps the most jaw-dropping intrusion of Baden-Powell’s Neanderthal worldview comes in Part II during a survey of “insects about which a scout ought to know something.” He no sooner praises the honey bee for its “wonderful powers” of navigation and industry, than he drops this clanger from left (or should that be far right?) field: “They are quite a model community, for they respect their Queen and kill their unemployed.” More than a century after its first publication, reading Scouting for Boys can be as scandalously funny as sitting down to a large family dinner with some dotty and opinionated Colonel Blimp of an uncle who can be counted on to offend all refined and liberal sensibilities. I’m also relieved to realize that it wasn’t a reflection of some weakness in my own character that I could never get with Baden-Powell’s program. There really was something incoherent and fundamentally oafish about scouting. If I still had one of those uniforms today, I wouldn’t sell it; I would ceremonially burn it, all the while dancing around those flames and chanting, “Dyb, dyb, dyb.”

2 Comments

Jim Chapman

30/8/2021 06:26:15 pm

Dob, dob, dob.

Reply

Douglas Cassan

31/8/2021 11:03:57 am

The sartorial aspects of scouting never appealed to me either; in fact they were responsible for me shunning shorts for the last 65 of my 80 years. I do remember weekly games of British Bulldog though; these were savage survivalist exercises where my small size (I was a mere 4'10' in grade nine and didn't start to grow to 5'8" until grade 13) was an advantage. These fiercely fought battles took place in a church basement gymnasium with rough stucco walls. The exhausted winners were both bloody and beaming. It was great fun.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed