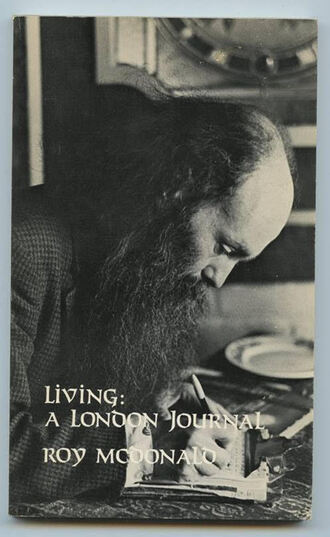

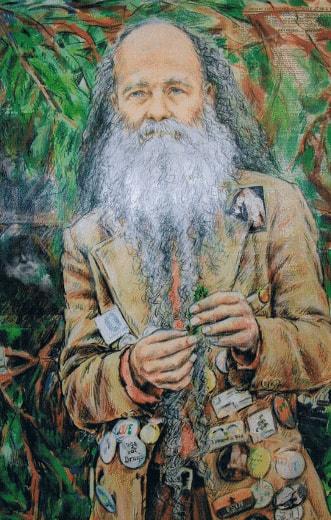

LONDON, ONTARIO – It’s been a melancholy week with the announcement of Roy McDonald’s death last Wednesday. The first reports suggested that he may have been dead for as long as three or four weeks before his body was discovered tucked up in bed in the house where he lived for all of his 80 years but that got walked back considerably and it is now believed that he’d been dead for only a couple of days. (Or maybe they’re just saying this, so we won’t go, “Eww.”) With no phone or internet connection he wasn’t the easiest guy to keep tabs on. Until fairly recently I usually managed to bump into him a couple times a year. Always at the Home County Folk Festival where he presided for all three days at the back of the mainstage crowd as a sort of non-musical attraction. And then, less dependably, I’d meet him standing outside of Joe Kool’s or the Starbucks at Dundas and Richmond where he’d plant himself and hold court with whoever passed by. In any of those situations, you’d have to hang around for about an hour to get in ten minutes worth of fractured conversation with Roy because he’d always pull in passersby and do the full introductions and bring everybody up to date and then that person would wander away and, “Ah, where were we? Yes, I’ve been reading this wonderful book about the holistic powers of organic cashews but the thing is you’ve got to eat them at a time when you’re . . . Oh, just a minute, Herman, have you ever met Ernest Forepaw?” And off we’d go again. It was maddening because I never cared about the stupid self-help books he was always reading or – perfectly pleasant as they all undoubtedly were – this parade of passing humans with whom he engaged in desultory chitchat. The vast majority of my encounters with Roy had this irritating garden party quality, this atmosphere of fussy distraction. It seemed I was always trying to draw a clear bead on this fundamentally likeable man whose life seemed so interesting in so many ways and yet never really found a way to take a deeper sounding. Could this incredibly wide circle of acquaintance that he cultivated so assiduously actually be a ruse for keeping people at a distance? Did anyone really know Roy well? The very best conversation we ever had was our first. We met in the early ‘70s at the Art Mart in the upstairs gallery over top of the old central Library on Queens Ave. I would’ve been about 22 years old and Roy about 37. My first novel was about to be published by Applegarth Press, I’d heard of Roy, read some of his stuff in (and seen his smiling bearded visage on one of the front pages of) my older brother’s stash of 20 Cents Magazines. He initiated the conversation and the next thing I knew, there we were, perched on the side of a plinth-like platform for showcasing sculpture and being told by a janitor-type that the evening was over, everybody else had gone and he was looking to close the place up. What had we talked about? We had both gone to Mountsfield Public School and we’d both dropped out of South so we had a lot of common referential ground between us. We somehow got onto the London flood of 1937 which my parents had gone through while they were courting and which Roy told me with a mischievous grin that he’d been present for as well. That flood was in April and Roy wasn’t born until June 4th that year but his mother had told him so many times about looking down from behind the old jail to survey the beginnings of the inundation in London West that Roy felt his muffled embryonic experience of the event qualified as at least a trace memory. I found that to be an utterly charming conceit and emblematic of his almost childlike gift for insinuating himself into situations. As the first London-based writer I’d ever talked with at length, I was also trying to mine Roy for insights on how to make a go of it as a writer in this town but I realized pretty early on that Roy wasn’t really making a go of it in any sustainable sense and that our whole approaches to life and wordsmithery were so radically diverse and even at odds that there wasn’t much in his experience that I could carry over or apply to my own situation. Still, I liked him and wished him well and in October of 1981, I wrote a big feature article on him for the Encounter magazine supplement of The London Free Press:

In the thirty six and a half years since that feature appeared, Roy never produced another book. No volume on Richard Maurice Bucke; no collection of subjective essays. When I was in charge of literary programming at the Forest City Gallery through the mid to late ‘80s, I booked Roy in twice to give readings and was a little appalled when, both times (and I begged him not to do it the second time), he dragged out The Answer Questioned and some other old chestnuts, including an oddly generic love poem to a woman named Rose, that I’d heard a dozen times before and always found banal and cliched. By about 1990 I simply stopped asking about new work and its progress because I could see it was not forthcoming.

Yes, he was apparently still blackening notebooks by the score and about five or six years ago he told me with some pride that UWO had agreed to archive all of his papers but - like the work of J.D. Salinger’s last, lost decades – was any of the stuff he was churning out intended for any sort of public consumption? Or was it all comprised of more diaristic jottings about chatting up coffee shop waitresses and the people he met in walking his London rounds? And did I have any right to be mystified or a little let down by the resounding anticlimax of it all? If greater expectations were ever in place, did Roy really put them there? As London’s most visible and widely recognized bohemian of the literary persuasion, Roy had stood four-square against the usual social, domestic and occupational pressures and trappings that can fritter away a writer’s concentration. In withholding all his focus and energies so as to keep his mind clear, he was committing himself to a pretty meagre and lonely life. I had once assumed – or maybe just hoped – that he’d foregone all those pleasures and comforts as part of some larger strategy that would leave him free to pursue some otherwise unattainable pearl of great price. Now I’m more inclined to believe that, no, that was just the way that Roy had to live and he was lucky enough to live in a family and a town and among a circle of friends who helped him get away with it. Walking my dog in the wee hours of most mornings, we’ll sometimes come across one of those ancient trees that are so substantial and gorgeous that when the folks from the City laid down the sidewalk for that block, they took a little jog with the otherwise arrow-straight pavement so as to accommodate its base and allow it to continue thriving. I didn’t know why at first but Roy McDonald always pops into my mind.

9 Comments

Barry Wells

26/2/2018 05:36:05 pm

As I understand it, the London Free Press date of Roy's demise of February 20 is merely an approximation, one settled on as a matter of convenience after the police found him on February 21st.

Reply

Ronalee Porter

28/2/2018 01:38:39 pm

I loved Roy. His simplicity, his honesty and he was genuine. What you saw was what you got. I worried about him during that very cold period of time we had in January and February and prayed he had something really warm to wrap himself in. It may have only been newspaper. Barry Wells, I too would like to think he passed on Valentines Day, as he was like Cupid. He would smile at you and you couldn't help but feel love and joy when he spoke with you. I will miss him dearly, like so many others. RIP my dear Roy.

Reply

Vincent Cherniak

26/2/2018 07:54:47 pm

Great profile and tribute. That’s the portrait of Roy I’ve been wanting to read… good on ya, lad.

Reply

SUE CASSAN

26/2/2018 08:12:13 pm

What a wonderful tour of the life, times and home of local celebrity, Roy McDonald. He had devoted friends. Roy faithfully attended every poetry reading and literary event he could get to and might try to flog some books at the event. His life posed a conundrum. Although his living conditions were austere, he lived in his childhood home without benefit of heat and services, he had the time so many of us wish for, to write and read with no distractions, like jobs, relationships, or even household chores. Roy’s affability and generosity in sharing his interests with anyone who was willing to listen seemed to indicate he was living the life he wanted. But, I wonder if the constraints and discipline of navigating life answerable to employers, families, and friends sharpens motivation to accomplish goals. Robert Frost defined freedom as “moving easy in harness “. We’ll never know what would have happened if Roy had been willing to shoulder a harness.

Reply

Herman Goodden

1/3/2018 12:42:15 pm

Susan - Your comment about Roy never shouldering a harness touches upon a theme I almost put in the article but decided not to. Sometimes, feeling overwhelmed by the number of plates I had to keep simultaneously spinning on the end of sticks as a freelance writer, I'd longingly look over at Roy's disengagement with the workaday world and wonder if he hadn't chosen the better path. But then I'd also twig to his adriftness and his loneliness and would become quite magically reconciled to an occasional overdose of pressure or divided focus in my own so-called career.

Reply

Derek Skidmore

26/2/2018 10:18:57 pm

About 35 years ago, I asked Roy if he'd consider cleaning himself up to work as a librarian, obviously a compatible calling.

Reply

Ted Goodden

9/3/2018 09:35:25 am

I don't see any mention of Roy's "estate"- if that word applies here. I know he was a dedicated diary/journal keeper and he occasionally talked about writing projects (Maurice Bucke, for example, and his connection with Walt Whitman, interested him). I was in high school when I first became aware of Roy as a public figure...I can recall one evening, after several beers and no prospects for further fun, suggesting to some friends that we should go to Country Style Donuts and talk to Roy. We did this ironically I suppose but it was a remarkable conversation that we had that night.. us up and left us with stuff to think about. After then, I began to value Roy and rely on his sincerity, thoughtfulness and abiding presence as an accessible wise guy. He was London's Writer-in-Residence. My question is: what did he leave behind?

Reply

Barry Wells

9/3/2018 02:42:22 pm

In the "estate department," a home on Wellington Road near Whetter Avenue likely worth $150K-$200K surely qualifies.

Reply

Geraldine Akiens

13/9/2022 01:18:58 pm

I lived beside Roy from October 2009 to his death. My son Christopher, an electrician, had bought the house in July 2008 but died as a result of a car accident on his way to work in Sarnia. So I took over Chris'house and his lively neighbor Roy. One day Roy and I were talking and he told me about Chris helping him out by cutting down a tree. Chris had left a note for Roy about doing this and as many attest to,Roy still had Chris'note. He went inside and amid all of his "everything he saved" he found that note. It was a precious moment for me to know that he had helped Roy. Seeing Chris'note brought tears to my eyes. Roy's house was ultimately cleaned out and his books that were salvageable went to the man who persevered through that process. Yes, Roy died in bed and one night my grandson woke me about two thirty telling me the police had broken into Roy's house. Roy had been unseen for many days. In retrospect I had noticed that his usual footprints in the snow were gone for awhile. He died as he lived.... his way!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed