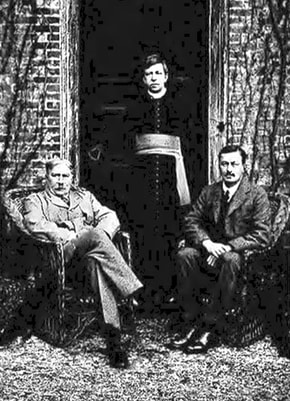

Robert Hugh Benson 1871–1914 Robert Hugh Benson 1871–1914 LONDON, ONTARIO – In a spirit of defiance I rise to my feet and proclaim that for the last couple of months I have been poring through a half dozen samples of the prodigious literary remains of Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson (1871–1914) and ... I’m afraid there’s no other way to put this ... I've been having a wonderful time. This wasn't supposed to be possible. If you're aware of him at all, perhaps you too have heard the discouraging reports spoken against this priestly powerhouse of an author who in the final ten years of his life following his Catholic ordination (and having published nothing in the thirty-two preceding years) produced a total of thirty-seven books including ten works of apologetics, sermons and religious biography, three devotional works, one volume of verse, two children’s books and twenty-one novels. Though Benson's staggering fictional output - averaging two novels per year - was just as riddled with religious themes as his nonfiction, the sales and buzz were far greater. Included in his fictional wing were nine contemporary novels, nine historical novels and three novels set in the future. This last category includes his single bestselling work, The Lord of the World (1907), which I first saw referenced as a sort of great precursor back in 1996 when Canadian artist, iconographer and author, Michael D. O’Brien exploded onto the literary scene with his first novel Father Elijah: An Apocalypse. Almost as lastingly popular is Benson’s later novel of Catholic persecution in Elizabethan England, Come Rack! Come Rope! (1912). Today that rather zealously pitched title (complete with exclamation marks) can cause more fastidious souls to roll their eyes and shudder. (My good man, must you always be quite so strident in your fulminations?) But I fancy such squeamishness speaks more to our present spiritual insensibility than any hysteria of Benson's. The book has never gone out of print because it's so compellingly - and horrifyingly - readable. And that now-risible title is actually drawn from the historical record, hailing back to an exhortation by the novel's real-life figurehead, the English martyr-priest, Edmund Campion, whose torture and execution at the hands of the state provides the menacing backdrop to Benson's tale . Having been shooed away by nearly a century's worth of right-thinking critics insisting that the man is just a wee bit fanatical and not quite respectable, I had to overcome considerable discouragement to even begin looking into Benson’s oeuvre. Pushing aside such warnings doubtless contributed to the frisson of illicit excitement I've experienced in daring to give him a chance anyway. And now, against all expectations, that excitement has been multiplied by the realization that R.H. Benson is actually a more than competent writer. I guess it could be the case that, operating by blind and bumbling luck, I have taken up the only half dozen good books that the man ever wrote. But were that so, even that happens to be five more worthwhile books than I would attribute to certain other Edwardian authors who similarly repeated a few pet themes over and over again, yet are still held up as worthy purveyors of tales, such as Henry James or H.G. Wells. (Which is to say I do still treasure The Turn of the Screw and The History of Mr Polly.) Look, I don't want to overplay my hand here but I do think a little restitutional justice is in order.. Robert Hugh Benson may not be a literary colossus of.his age and I may eventually determine that I do not have to read everything he wrote. But I have already read enough to declare that this man does not belong in the doghouse which an unquestioned critical consensus has built for him. R.H. Benson, familiarly known as Hugh, started out his life in a beautifully appointed manse. He was the youngest child of the manic-depressive Archbishop of Canterbury, Edward White Benson and a goodhearted mother, Minnie, who never would have admitted how much more congenial her life became once she'd achieved a comparatively early widowhood. Though Hugh was the only sibling to take on holy orders, none of the five Benson children ever married or had children. Barring famine, war or some other cataclysmic visitation, when a family line goes utterly dead like that in a single generation, it tells you something about the quality of the home life they've endured. It also, I suspect, tells you something about the sustaining properties of a religious tradition when the only ecclesiastically inclined son of the leader of a country's church goes running for his life to the Dogans. All five Benson children had marked intellectual gifts. Less immediately apparent to the outside world was their other paternal inheritance of a crushing proclivity for depression. One sister, Nelly, who bore that burden most handily - and was the only one of the children who could stare down their father when he was on a bullying tirade - was carried off by diphtheria in her twenties. The other sister, Maggie, who suffered most hopelessly with depression, was driven mad for the final decade of her life though this mercifully lifted in the last few weeks before she too died prematurely, from dropsy. The three sons also struggled mightily with the gloomy curse but developed variously effective strategies for coping. Getting out of the parental household as early as possible seems to have been key; an option not so open to unmarried daughters. And each of the sons in their differing way was eventually able to turn their hand to writing - all with a considerable measure of success - and taking the time to sort out one's impressions on paper always gives a person a fighting chance to overcome mental strife. The oldest brother, Arthur (A.C.) became a Master of Magdalene College and a popular essayist, memoirist and biographer of poets and artists. He’s only really remembered today for supplying the words to Edward Elgar’s anthem, Land of Hope and Glory. Arthur would fall apart emotionally for whole seasons at a stretch and be nursed back to serviceable shape by Fred (E.F.), the family fixer. It is Fred who sold the most books in his lifetime and retains the largest readership today with his beautifully-tuned comic novels featuring a pair of scheming socialites in the picturesque town of Rye, Mapp and Lucia . Of all Hugh’s siblings, Fred was the most able to steadily function because, like P.G.Wodehouse - another light writer of real genius who made his debut at about the same time - he made a point of never going deep on anything. Needless to say, Hugh came with a quirk or two of his own; most notably (and despite his profound Christian understanding of life and death) he could never shake a morbid life-long terror of being buried alive. He began his religious vocation in the family firm, taking Anglican orders in 1894 so that two years later, he got the nod to read out the litany at his father's funeral at Canterbury Cathedral. In the wake of his father's death Hugh began a half decade of struggle regarding his vocation. Following much the same trajectory as Cardinal John Henry Newman almost sixty years before when he valiantly sought to reconcile Anglicanism with its pre-Reformation roots, Hugh also gave up the C of E as a hopelessly compromised vessel of divine truth and converted, being ordained a Catholic priest in 1904. In a followup letter to a retreatant who had questions about a lecture he'd given, Monsignor Benson expressed his conviction that conforming yourself to the demands of a just and objective authority isn't just helpful when it comes to determining which religion you should follow; it was also a useful recipe for banishing any tendencies to depression: "As regards depression," he wrote, "I meant that the cause of depression is subjectivity, always. The Eternal Facts of Religion remain exactly the same, always. Therefore in depression the escape lies in dwelling upon the external truths that are true anyhow; and not in self-examination, and attempts at 'acts' of the soul that one is incapable of making at such a time . . . I would say that the 'subjective prayer' and self-reproach, and dwelling on one's temporal and spiritual difficulties, is not good at such times; but that objective prayer, e.g. intercessions, adoration, and thanksgiving for the Mysteries of Grace, is the right treatment for one's soul. And of course the same applies to scruples of every kind," In his brief but insight-packed survey from 2007, Some Catholic Writers, Notre Dame University's prof of Medieval Studies, Ralph McInerny, gives a characteristically fair appraisal of Hugh Benson's qualities as a priest and writer: “In Benson we do not find the intellectual acumen of a Newman nor the learned sophistication of a Ronald Knox. There is something superficial and freelance about him, something ‘enthusiastic’. Once in the Church and ordained, he managed somehow to avoid most aspects of the priestly life. The pastoral side repelled him; he was simply no good at it. His preaching was acclaimed, though its theology was sometimes shaky. The writing of novels was for him a kind of extension of his preaching. The wonder is that so many of the novels are as good as they are. Taken all for all, Robert Hugh Benson is one of the most interesting turn-of-the-century converts.”  The three Benson Brothers: A.C., R.H. and E.F. The three Benson Brothers: A.C., R.H. and E.F. In his 1991 biography of E.F. Benson, Brian Masters discusses Hugh's gifts as a preacher while recounting the impact his death from pneumonia had on his older brother. Though the biographer largely shares Fred's frequent exasperation with the over-enthusiastic Hugh, in this passage he strives to pay Fred's baby brother his due: "Hugh's loss was felt very keenly by the Roman Catholic Church, for whom he represented not only the supreme catch of a convert from the very arms of Canterbury, but a proselytizer of genius and a preacher with fire in his voice. There is no doubt that his influence from the pulpit was enormous. Whenever Monsignor Hugh Benson was due to preach one could be sure the hall, no matter how big, would be sold out months in advance. This was as true in America as it was in England, for Hugh gave a performance in the pulpit as certainly as Sarah Bernhardt gave on stage. The present author has heard from a Monsignor of the church that he was converted to Catholicism overnight, when he was a young boy, as a result of hearing Benson preach . . . Fred also paid tribute to his brother's tumultuous eloquence' and the 'flawless, flame-like' delivery of his sermons, but there was no secret that he was entirely out of sympathy with their content and was constantly irritated by Hugh's monumental certainty which caused many of the arguments in the family." Shortly after coming into the Church thirty-seven years ago, I read Hugh's Confessions of a Convert, and was perhaps not yet sufficiently formed to see past the sort of triumphalism, the 'rah-rah-rah'-ness that McInerny notes above. I subsequently passed the book along; an act which I now regret as I’d like to give it another shot. I want to give it that second chance because I was so impressed by a more recent reading of his Paradoxes of Catholicism, which collects a series of sermons he was invited to give at the Vatican over Easter of 1913. In these sermons recast as essays, Benson does a masterful job of not just explaining but reconciling such apparent conundrums of the Catholic faith as Jesus Christ, God and Man; The Catholic Church, Divine and Human; Peace and War; Wealth and Poverty; Sanctity and Sin; Joy and Sorrow; Love of God and Love of Man; Faith and Reason; Authority and Liberty; Corporateness and Individualism; Meekness and Violence; The Seven Words; and Life and Death. I have also read a rather modest collection of his pious poems; all quite straightforward but worthy nonetheless; such as this short meditation on Patience: I waited for the Lord a little space, So little! in whose sight as yesterday Passes a thousand years: – I cried for grace, Impatient of delay. He waited for me – ah so long! For He Sees in one single day a loss or gain That bears a fruit through all eternity – My soul, did He complain? But what really activated my renewed interest in Benson was my reading after Christmas of one of his final novels from 1913, An Average Man. It is a contemporary novel of Edwardian English life which contrasts the approaches to Catholic faith made by two very different men. The first is a bright and unencumbered middle class young man with ever-improving prospects who is just starting out on his way up the ladder of life. The second is a rather dim, middle-aged C of E curate with zero hope of advancement who is married to a bitterly ambitious wife who fancies herself as an artiste. I admit that I took up the book with low to middling expectations which perhaps helps to explain the magnitude of my surprise and admiration. It is a brilliantly accomplished novel which treats all of its characters sympathetically and ingeniously lays out the earthly challenges and perils that can waylay a heart that has been called to a more robust communion with God. And more recently yet I have been immersed in his two big tub-thumpers,The Lord of the World and Come Rack! Come Rope!. In the first book, I was struck in an incidental way by this account of a Catholic Bishop's struggle to shore up the faith of a priest who is well along the road to giving up his calling and defecting to the thimble deep quasi-religious movement of humanism that is sweeping the globe.: “Percy had really no more to say. He had talked to him of the inner life again and again, in which verities are seen to be true, and acts of faith are ratified; he had urged prayer and humility till he was almost weary of the names; and had been met by the retort that this was to advise sheer self-hypnotism from one angle, yet from another they are as much realities as, for example, artistic faculties, and need similar cultivation; that they produce a conviction that they are convictions, that they handle and taste things which when handled and tasted are overwhelmingly more real and objective than the things of sense. Evidences seemed to mean nothing to this man.” Though she was not taking her lead from Benson, decades later, mystery writer, Dante scholar and notably sane feminist, Dorothy L. Sayers, elaborated on this likening of man’s religious and artistic faculties in her fascinating book-length analysis of divine and human creativity, The Mind of the Maker (1941). Taking the Holy Trinity as the archetypal model for artistic creation, Sayers posits that the Father represents the originating idea or flash of inspiration, the Son is the incarnation of that idea into a form that can be sensibly perceived, and the Holy Ghost is the two-way flow of nourishing energy by which a created work communicates its meaning. “And these three are one,” Sayers writes, “each equally in itself the whole work, whereof none can exist without the other; and this is the image of the Trinity.” In these two Benson novels - one futuristic and one historical - a program of remotely orchestrated societal upheaval that reaches into every cranny of public and private life is being loosed in order to bring about a new kind of order that nobody except some inaccessible elite actually wants or understands with any precision. Tell me if this kind of paralyzed uncertainty doesn't ring a bell or two for you right now: “But imagination simply refused to speak. The daily papers had a short, careful leading article every day, founded upon the scraps of news that stole out from the conferences on the other side of the world; [The new leader's] name appeared more frequently than ever: otherwise there seemed to be a kind of hush. Nothing suffered very much; trade went on; European stocks were not appreciably lower than usual; men still built houses, married wives, begat sons and daughters, did their business . . . for the mere reason that there was no good in anything else. They could neither save nor precipitate the situation; it was on too large a scale. Occasionally people went mad – people who had succeeded in goading their imaginations to a height whence a glimpse of reality could be obtained; and there was a diffused atmosphere of tenseness. But that was all. Not many speeches were made on the subject; it had been found inadvisable. After all, there was nothing to do but to wait . . . It was possible to hate [the new leader], and to fear him; but never to be amused at him." I often remember a typically vulgar riff of Lenny Bruce's in which he pointed out how interesting it was that whenever you heard someone banging on about how "the Church wouldn't let you do this" or "the Church has always stood for that,"' nobody ever assumed they were talking about the Presbyterians or the Baptists. You knew full well it was those damned RCs they were railing against; the oldest church, the biggest church and the only church so monumentally distinct that they didn't need a denominational tag to identify themselves. Needless to say, in both of Benson's novels the Catholic Church is enemy number one for those seeking to impose a new dispensation. In The Lord of the World Bishop Percy starts collecting some of the new leader's more sinister maxims; each one of them a pointed refutation of longstanding Catholic doctrine: "No man forgives; he only understands." "It needs supreme faith to renounce a transcendent God." "To forgive a wrong is to condone a crime." "A man who believes in himself is almost capable of believing in his neighbour." "The strong man is accessible to no one but all are accessible to him." By the end of The Lord of the World, all of Rome has been bombed to smithereens, the Church is in disarray everywhere and Percy, holed up in the Holy Land, is appointed as the makeshift Pope of a ragged remnant of a Church that braces itself to face the global force of humanism in a final conflagration. Benson writes that Percy "could not have described it consistently even to himself, for indeed he scarcely knew it: he acted rather than indulged in reflex thought. But the centre of his position was simple faith. The Catholic Religion, he knew well enough, gave the only adequate explanation of the universe; it did not unlock all mysteries, but it unlocked more than any other key known to man; he knew, too, perfectly well, that it was the only system of thought that satisfied man as a whole, and accounted for him in his essential nature. Further, he saw well enough that the failure of Christianity to unite all men one to another rested not upon its feebleness but its strength; its lines met in eternity, not in time. Besides, he happened to believe it.” That last personal note of orneriness is the perfect grace note to what strikes me as a brilliant exposition of the Church's wondrous capacity for proliferation and survival over two millennia and counting. It reminds me of a wonderful story of the English writer, Hilaire Belloc - himself, an early fan of Benson who encouraged him to write novels of Reformation-era Britain. On a lecture tour in the States, Belloc dropped into an inner city cathedral for Mass. Blithely unaware of the local variations, Belloc knelt or genuflected according to the rite of his home parish in Sussex. About two thirds of the way through the service, a priest approached Belloc and whispered, "It is customary at this point for our people to kneel." Belloc turned on his fussy interloper and whispered right back, "Piss off," to which admonishment the priest backed away, saying, "My apologies, Sir - I didn't realize you were Catholic." Benson and Belloc both understood another one of those great "paradoxes of Catholicism". In Her innate multiplicity the Catholic Church does indeed take on distinct corporate forms in each nation and region of the world. But She does not do this in pursuit of any sort of globalism or humanism. The goal here is a true universality which can only take place one ornery soul at a time as the faith is embedded and nurtured in the heart of each individual.

3 Comments

Mark Richardson

1/3/2021 01:44:38 pm

Thanks for this, Herman.

Reply

Paula Adamick

2/3/2021 09:08:15 am

What an irresistible piece ... no wonder you've been having fun. I bought most of RH Benson's books in 2008 but, as is my way, read only one.

Reply

Max Lucchesi

3/3/2021 11:45:35 am

A footnote to forgiveness Herman, the old saying that: ' A woman forgives, but never forgets. A man forgets but never forgives'. Of all the Catholic authors that were rammed down our throats Hugh was not one of them, though with his antipathy to liberalism he should have been. It's to his credit that he served one of the better Popes.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed