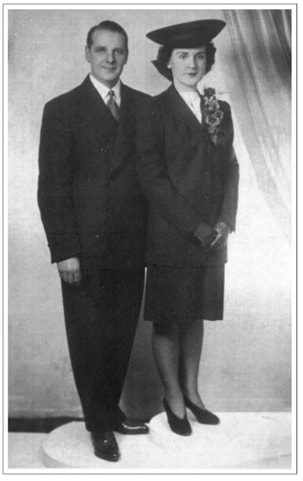

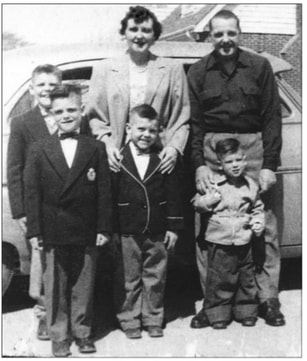

LONDON, ONTARIO – My father died seventeen years ago this week. It’s not a very round number; not the kind of anniversary that would ordinarily be marked in any elaborate way. But David John Goodden (1914–2003) has been much on the minds of all four of his sons this fall as the fraternal chain correspondence we’ve been compiling and circulating for the last several years sprang into particularly vigorous life in September. Perhaps not so coincidentally, that was when we planned to get together for a reunion in Italy until the Chinese Batflu pandemic knocked out the possibility. It’s always great to get together with any of the brothers but there’s a special frisson – a sort of snapping into place of all the components that empower a full electrical circuitry of pure unadulterated Goodden-ness – that occurs when all four of us are physically re-constellated in our original formation. During our last reunion in Australia in 2014, we rented a van for a four day tour of the south-eastern island-state of Tasmania. One night we lucked into accommodation at a beautiful inn on a steep hillside in Bicheno with a heart-stopping view of the ocean and nocturnal visits from a thundering herd of kangaroos. The next morning I dropped into the manager’s office to pick up some e-mail with his wi-fi and walking me back down to our van, he said he’d never hosted an expedition like ours before. “I think a lot of people would like the idea of doing what you’re doing,” he said, “but then they’d have to ask themselves, ‘Could I really stick it with my family for three or four weeks?’ You fellas really seem to get along. You’re lucky that way.” Indeed we are. And now – when I am 68 and my brothers are all in their seventies – we’ve discovered that we can achieve something almost as rich as a physical reunion by mingling our recollections and speculations in this way and creating a broader and more multifaceted narrative than any of us could achieve from our own vantage point alone. We’ve been particularly focussed this fall on Jack’s early life, before any of us even constituted a gleam in his eye. It was in many ways a harsh and difficult early life which Jack did not allow to embitter his perspective when it came time to start raising children of his own. As a complement to the brothers’ investigations into Jack’s prehistory, I set down here a sequence of more public essays which I wrote in the years just before and just after my father’s death. "NOTHING BUT DAILY EXPERIENCE could make it credible, that we should see the daily descent into the grave of those whom we love or fear, admire or detest; that we should see one generation past, and another passing, see possessions daily changing their owners, and the world, at very short intervals, altering its appearance, and yet should want to be reminded that life is short." In this excerpt from one of his sermons, Samuel Johnson uses the word "want" in the meaning of "need"; finding it odd that we are constantly surprised at nearly every stage in our existence by the swiftness of time's flight. One summer evening in about my twentieth year, I was sitting on the top step of the front porch with my dad who then would have been pushing sixty. He pinched up a fold of skin on the back of his hand and released it. He asked me to do the same with mine and compare the differences. My ridge immediately snapped back. His stood there for about five seconds in a most alarming way, then was slowly reabsorbed back into that plane of flesh between his knuckles and wrist. "Is that ever gross," I said, with all the compassionate sensitivity of youth. Now in my forth-eighth year, I've been pinching the back of my hand all day and feeling a sort of uneasiness that it doesn't snap back like it used to. On an intellectual level, this is hardly surprising. I can't say my dad didn't warn me. But on a level more instinctual than reasonable, I find this perfectly natural development upsetting. Johnson was right. Human beings can be remarkably vain and blind to the larger processes we're caught up in. I'm mulling over age and decrepitude partly because the season of Lent approaches when the well-trained Catholic mind naturally inclines toward thoughts of mortality. But what really set this off has been watching my dad - now closer to ninety than eighty – hand over his car keys for the last time. My brothers and I have been pussyfooting around this sensitive issue for years, knowing how much Dad's identity and sense of self-worth (never mind trifles like independence and happiness) will be challenged at the prospect of no longer being able to take his car out for a spin. His hearing has been dodgy for decades and now his vision is just about as bad. Finally, it was my wife who had the gentle determination to convince all of us that it was past time to summon all our courage and face this new reality before something really awful happens with him behind the wheel. A superb driver with a flawless record, Jack earned his living as a salesman for Canada Packers, racking up so much mileage that every year the company provided him with a shiny new car. I only appreciated how uncannily good a driver he was when I started taking lifts with other people who weren’t even in his league. I’ve never seen anybody else with the utter serenity and competence that enabled Jack to keep up his end in a conversation while navigating a slippery hill in an ice storm. If Jack knew how to hold 'em in all kinds of emergencies, he also knew when to fold 'em. His only car that ever got totalled was literally run over by a cement truck. One hot summer day, travelling between calls in some godforsaken patch of Northern Ontario, there was roadwork going on. A whole line of cars was stopped on a soft incline – Jack was in the middle - when he saw that the loaded cement truck immediately in front of him was starting to slip backwards in the loose gravel. Having no other option, Jack scooped up his briefcase and stepped out of his car just as the churning behemoth rolled up over his hood and flattened it. Possessing a profound disinclination for all things mechanical (that would be my mother's genetic legacy) I never bothered learning how to drive. That doesn't mean I don't understand what a wrenching passage this has been and what courage and grace Jack has shown in accepting his new situation. As consolation, he knows that his were the real glory years of motoring; that no mentally competent or non-delusional person today gets into their car - as he routinely did - with a sense of pleasure and relaxation. In an exchange which is destined to join the skin-pinching episode in my pantheon of life's benchmarks, Jack told us today while handing over his keys to, "Use your eyes while you've got them. I know I don't see as well as I used to but it's still a beautiful world." – January 2001 OH, THE WRETCHED INDIGNITY of it all. First we take away his car keys, and then we come for his castle. We're helping our parents move out of the big family home on Wortley Road in old south London – a two storey, mock-Tudor monster with a finished attic and basement and an obligatory wall of ivy on the south-facing wall. The challenge by the end of the month is to somehow boil down four floors worth of stuff that's accumulated there since 1964 into a much smaller cache which can be contained in a two-bedroom apartment in London’s seniors plantation otherwise known as Cherryhill. All four Goodden sons were launched into the world from that house. The first-born made it all the way down to Australia while the younger three all bought homes in town huddled around the forks of the Thames. So perhaps the younger trio weren't launched so much as we sort of keeled over sideways on the pad. But just because the apples didn't land very far from the tree (or would nuts be a better metaphor in this instance?) that doesn't mean we aren't all being emotionally tortured and wrenched out of shape by the process of emptying out the homestead. If ever there was a home on this earth which I somehow assumed would last forever, then my parents' home was it. Theoretically, ideally, I've always paid lip service to the futility of laying up treasure on this Earth. But all the while I've assiduously compiled a library of books and a music collection that far outstrips what anyone could ever claim to "need". My stash is still safe for now but in watching my parents divest themselves of most of their possessions, I realize at a more visceral level than ever before that the prophets were right; that here indeed we have no continuing city. It's uncanny, almost dream – or nightmare-like – how elastically long it can take to sift through material that's so drenched in memory and meaning. Going through some tools on the basement workbench, my wife saw and heard both my London-based brothers happen upon the old battered shoe-shining kit for the first time in decades. Both released the same involuntary sigh of recognition and both had to lift the bent tin lid and go rooting through the box, handling and sniffing congealed old tins of Kiwi polish, waxy rags and stiffened, mangy brushes. Then there was the cardboard shoebox full of school report cards for all four boys. What an ambition-deficient crew we apparently were. To save time and prevent wrist-cramp in their teachers, the Board of Education should have just had a rubber stamp made up which could have been used each term for each child: "Goodden needs to try harder." I spent the better part of Saturday afternoon tumbling down one time-tunnel after another up in the attic. I couldn't tell you what I went up there for originally. Whatever my mission was it evaporated when I ascended the steep wooden stairs and inhaled the warm, cedary smell of that long, low room with cardboard walls where I hosted a hundred sleepover parties. I used to cram about a dozen friends up there late in the summer for our Annual Sophie Tucker Memorial Film Festival. I suppose it was a more elaborate precursor to what we now know as a night in with the VCR. We'd put a refundable deposit on a sprocket projector and borrow a stack of metal canisters filled with features and shorts from the National Film Board office downtown. We weren't fussy about artistic merit or interesting plots. Sometimes the worst films were the most fun. We always got at least one over-bearing clunker with a gormless title like 'Dating Dos and Don'ts for Canadian Teens'. The Norman McLaren animated shorts were wonderfully ingenious, but even the dreariest documentaries on logging or smelting somehow became magnificently amusing once we'd passed around a bottle of my brother's vile (but potent) home-made dandelion wine. Another big favourite with festival patrons was a cartoon from the ‘50s that brought the illustrations to life from the classic American children’s storybook, Mike Mulligan’s Steam Shovel. What really finished me off last Saturday was coming upon box after box of ephemera relating to my so-called career. Newspaper and magazine articles I've written, posters and programmes for readings and plays, reviews of books and plays - it was all there, carefully frogged away, annotated and dated in my mother's script. The sheer quantity of it all floored me. What a river of words has kept me afloat these last thirty years. Then I looked over to the south-east corner of the attic where I was mooching around one night in my eighteenth November when I lifted up an old army blanket to inadvertently reveal my parents' Christmas gift for me. It was an antique Remington Noiseless typewriter, circa 1920, with 52 black enamel keys encircled in gleaming chrome. Everywhere you looked - down through the keyboard, in through the half-moon hole in the top plate - you could see all the beautiful moving parts and the incredible series of mechanical reactions set off by pressing any key. It was love at first accidental sight. Of all the gifts I've ever received, that first in what would turn out to be a veritable fleet of Remington Noiselesses always stood out as something of life-changing importance. More than anything else, it symbolised my parents' blessing on my chosen career. "You want to be a writer," they said. "Here's the tool. Go ahead and be one." And three floors below that is the basement study where – with their indulgence – I'd pack myself away for days and weeks at a stretch, working out my destiny as a four-finger typist and "vendor of words" (in St. Augustine's self-deprecating phrase) with a maximum speed of twenty words a minute. Last Saturday was the first warm and sunny day of the spring. Dad hasn't been able to say very much all month because of the gloomy, looming deadline of his eviction. Yet he rose to the occasion courageously, donning a full suit (which has become a rare sighting indeed since he retired some twenty years ago) for this final day before we utterly disassembled his world. We sat around on the porch together after we’d finished all the sorting and packing up, urging occasional passers-by interested in the mounds of cast off furnishings and articles at the curb to neatly help themselves. During a lull in our conversation Jack went through to the back pantry and re-emerged with a tin of Brasso and a soft rag and commenced polishing up the metal numbers on the wooden plaque to the right of his front door. He isn't going to be able to sit on that porch this summer, basking in those numbers' reflected glow. His time here is up. This was something he did for the next people. – April 2001 MY DAD LOST HIS BEST friend last month and Jack couldn’t even make it out to Bert’s funeral because he was laid so low with his annual bout of pneumonia. Of all the cruel frustrations that old age piles on us; that must rank among the hardest. It isn’t bad enough that you have to watch lifelong friends stumble and fall away; now you don’t even get to say your goodbyes. ‘The old man’s friend,’ they euphemistically call pneumonia for its knack of briskly carrying off the infirm rather than letting them languish in suffering decrepitude. But for the better part of a decade now, pneumonia’s only been playing ‘nicky-nicky-nine-doors’ with Jack. It settles into his lungs each November with the apparent intention of finishing him off. It troubles his breathing and saps his energy for a few weeks but ultimately seems to change its mind and shoves off, leaving Jack to fight another merry round next year. Quite maddeningly, the only sense in which pneumonia could be called Jack’s friend is that he gets to see it a lot more frequently than his actual human friends. My brother Bob and I visited at the funeral home with Bert’s widow and sons in Dad’s stead, extending his and our condolences and hearing all the great stories one more time. They first met as young bachelors working at the Dominion grocery store downtown. Bert went on to run his own grocery store on Blackfriars Street just west of the old bridge and Jack became a salesman for Canada Packers. When the spring runoff of 1947 looked set to repeat the great London flood of 1937, Jack was part of the emergency crew who pitched in through the night to help Bert haul all of his produce up to the second floor. When the floodwaters crested and began to recede the next morning with no damage done, this sleepless crew then switched into reverse, bringing everything back downstairs. You wouldn’t perform that kind of donkey work for just anybody but you would for the guy who, sixty-one years ago this September, loaned you his car for your honeymoon. A full tank of gas and, “Here’s the keys,” with no stipulations or conditions or expectations of repayment; just a whispered aside that you should, “Try not to smash it up, okay?” Bert and Jack were a perfect match of temperaments, customarily existing on a plane of easy-going serenity that could exasperate more ambitious or competitive types. Once they were both retired, they finally had the opportunity to spend as much time together as they liked. Their lax and unfocussed golf games were legendary. Like drivers who pull over to let every tailgater and hothead pass, they were always stepping aside so more time-pressed golfers could play through. They were never known to do anything so anally retentive as keep score. On the few occasions I accompanied them o’er the links, I was about equal parts charmed and appalled at all the fudging tricks they’d get up to – like retaking drives gone wrong, kicking the ball from the sand trap onto the green and guiding wayward putts into the cup with a subtle tap of the shoe. When I was about nineteen, out of school, unemployed and not exactly dazzling my parents with my commitment to the capitalist work ethic while living under their roof, I was writing a lot and managed to land a poem in a Canada wide poetry anthology. Bert somehow caught wind of my little victory and congratulated me when he was over for a visit. I could see Jack was about to say something caustic about my lack of income and I’m pretty sure Bert saw it too. Because the next thing he did was head Jack off at the pass, saying: “Good for you. I can see you’re going to make your living by using your head unlike your poor old dad here. Isn’t that right, Jack? It’s good to see a kid use his brains, isn’t it?” What could Dad say but ‘yes’? I always meant to thank Bert for that kind turn and perhaps I have over the subsequent years by occasionally inserting myself between my own friends and their kids in a similar way; just reminding these frazzled dads what every parent sometimes gets too close to properly see. – December 2002 MY FATHER DIED SATURDAY, December 13, 2003, at 4:10 p.m. This most reluctant of emigrants had been born in the back of his family’s butcher shop in Rhymney, Monmouthshire in Wales on April Fool’s Day, 1914 and breathed his last, eighty-nine years, eight months and twelve days later on the sixth floor of London’s St. Joseph’s Hospital, just as the late afternoon sun, shot through with delicate pink and blue streakings, was starting to flood into his room. Jack often spoke about the most desolate moment of his life as he stood all alone, a just-turned fifteen year old kid with a cardboard suitcase, clutching the guardrail of the transatlantic steamer, Megantic, as it pulled out of Southampton on an eight-day crossing to Halifax. Dad’s family had fallen on hard times and as the only son, it was his task to go on ahead to the new world and make smooth the path for his parents and sister who would follow over in the fall. In exchange for his free passage to Canada, Dad was required to work on a farm – he didn’t even know where it would be – for a full growing season. He boarded a trans-Canada train in Montreal and at every station along the way, a few more British lads would have their names called out, would disembark and be led away to meet their employers. Jack’s name was called in Guelph where he and a parcel of other very young men were herded into a livestock arena to be inspected by farmers from the surrounding area. The farmers picked out the boys they wanted and took them away as virtual slaves-for-a-season. There were some horrific stories of mistreatment with this scheme but Jack was lucky. In addition to tending livestock on a three hundred-acre farm, Jack’s reading and writing skills made him useful as the farm’s official secretary and interpreter. With the late fall came liberation from farm work and the longed for reunion with his family. It’s probably no coincidence that it was right about then that Jack first encountered the two smells which he would always identify as his favourites in all the world – burning leaves (the Welsh autumn is such a soggy and desultory affair that such conflagrations aren’t necessary) and a steaming pot of boiling chilli sauce. The reunited family eventually made their way down to London where Jack and his father were able to pick up work in the family trade of butchering, though it wouldn’t be until after the Depression in September of 1941 with the prospect of full time work at Canada Packers, that Jack felt financially secure enough to marry a London girl with whom he’d long been besotted, Verna Geraldine McQuiggan.  Jack and Verna's wedding photo, 1941 Jack and Verna's wedding photo, 1941 But the world wasn’t quite through with horsing Jack around and in May of 1942, he got drafted into the army and spent the rest of World War II undergoing training in north-western Canada, where he said that all he really did was, “learn how to guard pine trees and hose out garbage cans.” Given compassionate leave in 1944 when my parents’ first child and only daughter, Barbara, died, Jack never saw service overseas. After a childhood and young manhood pocked with disruption and displacement, one can understand how it was that when this “very married” man (as my brother Ted called him on Saturday) finally put down roots, he planted them so deeply and securely that you couldn’t pull them up with a fleet of Roto-tillers. The home my parents created for me and my three older brothers was such a bottomless oasis of stability and love that we, in turn, could afford to take just those kinds of chances – with artsy careers and unorthodox living arrangements – that were guaranteed to drive poor old security-seeking Jack crazy. Carl Jung once postulated a theory that each generation, to some extent at least, is psychologically driven to live out their parents unlived lives. If each generation unfailingly explores just those facets of experience that their parents were determined or obliged to set aside, then it helps to explain the uniquely explosive dynamics of family life. It also suggests the unique possibility – rarely realized and requiring more hard work than most people today are willing to give – for the family, alone of all human groups, to achieve real psychological balance and wholeness. I was twenty-seven self-absorbed years old when I decided to interview my parents about their relatives and forbears for a family history which (smugly assuming I was the only Goodden who could write) I would develop into book form and distribute within our family as a Christmas present. The day I was to go over and see them, Jack turned up on my porch instead, dropping off a shopping bag full of prose memoirs; so polished, so funny, so uncannily like what I thought was my very own style that I could only sit in dumbfounded wonder and weep. Oh. So that’s where that came from. From that day on I’ve always been conscious that it’s Jack’s gift I’ve been precariously exploiting all these years as a means to earn my crusts. Though he may have doled it out rather sparingly at times, there was no one whose praise meant more to me. And his actions spoke as loudly as his words. Even with badly failing eyesight, having to sit in a pool of direct sunlight with a magnifying glass nearby, he always made sure that he read my columns. If you want to get technical about it (Gooddens are all fairly hopeless at medical details) David John Goodden (known as Jack to all his loved ones except Mom who’s always called him John), died of renal failure and had a couple of other systems that were shutting down as well. "Old age" is what we’re calling it. He rallied quite a bit after a couple of days in the hospital and was doing so well that the nursing staff began devising contingency plans in case he lasted another few months. Having called my brother Dave and his daughter Kate all the way up from Australia for the last stand, there were a couple days there where we fretted that Jack just might prove his team of attending physicians wrong. Then Friday at noon, he took a sharp turn for the worse; much like he had been that last night in his apartment when I had to help him into bed and almost called an ambulance. When he suddenly stopped moaning and fell into a deep sleep, I decided it could wait for the next day. Jack hated hospitals like our dog Badger hates visiting the vet. My feeling was, if he'd died that night in his own bed at home, then so be it. I was alone with him last Friday night for about three hours and saw him off into the morphine-drenched sleep from which he never woke. While we'd had better and more focussed chats over his previous ten days in the hospital (though his chronic hardness of hearing meant he got to do most of the talking and cruelly limited the subtlety of what we could express to him) I’m consoled to know I was the last person in the world to talk with him and do what little I could to make him more comfortable. Jack knew that his time was drawing nigh. A couple weeks before this final crisis hit, Jack told me of a dream in which a sage old man pronounced he would have five more months to live. That would've put him just past his ninetieth birthday instead of three and a half months before. It's been such a hard slog these last few years (after eight and half decades of pretty rude health) and his quality and enjoyment of life had decreased so much, that a large part of what we're feeling now is relief and numbness, regularly punctuated by shards of grief. All in all he had a good long run, exceptional considering he smoked for all but sixteen of those years. He never had to go into a nursing home like Mom and he kept his wit and his phenomenal memory right up until the very last lap. An hour after dying, the red veins that decorated his nose were all smoothed away and his skin had taken on almost an olive tone. The same with his lips. The effect was to make him look suddenly younger. His mouth was open and a little contorted and inside one could only see blackness; emphasizing the sense that this was just his shell, an empty husk he'd left behind. All of the brothers and wives and a smattering of kids just sat around for the better part of three hours, staring at him, touching him, crying and laughing and telling stories. It was all terribly sad but it was a good place to be. Mom was able to visit with him once in the hospital, though with her Alzheimer’s it’s hard to know what she'll remember of it. Considering that she couldn't tell you where she’s been living for the last two and a half years since we packed up the old family homestead, one wonders if Jack's death will ever really register on her consciousness. Or will he always be in the next room, fussing with something and about to come through? “What's keeping him, anyway? He should be here by now.” The blessings of oblivion, perhaps. Though he served a couple of terms as an elder at Calvary United Church in the ‘60s, church was something Jack seemed to indulge more for the sake of my mom than himself. He could feel a pantheistic sort of reverence and awe when looking at a mighty tree or a particularly fetching landscape. He was always grateful for the gift of life and considered Mother Teresa to be a great soul. But I think he was too constitutionally ironic to ever seriously entertain religious belief for himself. So I was glad the end came at St. Joe’s – a human-scale hospital with crucifixes on the walls and windows that can be opened to let in real air. And there were people praying for him (including a convent of nuns, which might have amused him) in Canada, Britain and Italy. All four of Jack’s sons were born at St. Joe’s, as were all three of our kids, and in a lot of ways, this death-watch felt like we were preparing for a different sort of birth. Certainly the stresses and pains that gripped him bore a resemblance to labour, as he prepared to deliver himself into another dimension. There was the constant vigilance of his family, huddled at bedside, watching for signs of imminence and for the call to go out that the great event was upon us; all of us anticipating that mind-melting moment when no one would enter or leave the room but the number of people therein would suddenly change. I keep a photograph of my son, Hugh, in my desk drawer that was taken on his second birthday. His big gift that year was an orange plastic, push-pedal tractor which he loved so much that he couldn’t bear the thought of getting off the thing to go to bed. So we let him stay up a bit longer and snapped this picture as he was starting to doze off, slumping forward on the steering wheel with heavy eyelids like a little drunk. After a year or so of very intensive farming, the steering wheel tragically snapped off. Though it didn’t work anymore, we knew there’d be a scene if we openly disposed of it. So we let him ignore it for a few weeks, then quietly took it out to the curb one garbage night after he’d gone to bed. A couple of hours later, just tucked into bed ourselves, we had second thoughts and my wife sent me out to retrieve it, only to discover that it had already been snapped up by some passing scavenger. My parents had been by that night and unbeknownst to us, Jack had scooped up the tractor on their way out and taken it home to his basement workbench where he fashioned and attached an ingenious new steering control out of copper tubing. He brought the magically restored tractor around a few days later and it enjoyed full and glorious use for another few years. That kindness - that gesture - encapsulates so much of what I’ll miss about this man. It sets off fond echoes from my own infancy when I’d gone to him with a plastic horse and cowboy set whose crappy plastic saddle had cruelly snapped in two. Could he fix it? I tearfully asked. He did better than fix it; he vastly improved it. With scissors and a bit of dark shoelace he trimmed and shaped a small leather crescent he detached from one of his old belts into a beautiful form fitting saddle that actually creaked when the cowboy hopped onto his steed. When all of our kids visited Jack that first day in the hospital, teary-eyed and all, they moved right in as if Jack was a new born baby, playing with his incredibly fine and wispy white hair and getting it to stand up Ed Grimley-style. When it was time to go, the two girls leaned in from either side and simultaneously smooched him on the cheeks, making him grin like a loon. I envied them their easy bedside manner and took courage from it. As a general rule, Goodden men aren’t very touchy-feely types but thankfully that rule was out the window as Jack’s final days rolled by. By the last few days, whenever my dying father turned over in his bed, putting out his hand for me to hold, I took it, and remembered the half century-old photo Jack always kept at his desk. In that picture, taken in front of his brand new 1954 Ford Meteor, I’m reaching up to hold the hand of this “very married” man as he stands with the five people who always knew they came first in his world. And I wondered why we ever stopped doing so simple and reassuring a thing while we still had the chance. – December 2003  The four boys: Dave, Ted, Bob and Herman The four boys: Dave, Ted, Bob and Herman I promise I’ll take up other subjects soon but with your indulgence, I’d like to gather up some of the aftershocks, echoes and consolations that have been rolling through my life since burying my dad in the week before Christmas. And tell you some of what we’ve learned. Setting foot in Jack’s apartment to help select photographs for a display at the funeral home, the place became what it never had been for me during his final two years of failing health: his home. That place I never thought I’d love – such an inadequate reflection of the man, such a tiny, architecturally banal parody of the sprawling home on Wortley Road where our family (and then just mom and dad) had lived for the previous 40 years – was suddenly transformed into a precious, haunted space that I cherished for its associations. Lesson learned: Home is wherever your loved one lives. Driving to the funeral home to be on hand for the evening round of visitations, I announced to my wife that for once in my life I didn’t have the funereal fidgets. I wasn’t filled with dreadful anxiety at the prospect of having to come up with useless condolences to pass on to heartbroken people. I actually wanted to be at the funeral home because I wanted to be with what was left of my father for as long as I possibly could be. I didn’t expect magical words of healing wisdom from anyone. It was enough that friends just be there. Lesson learned: Mourners don’t have to be eloquent and a simple, “I’m sorry,” can say much more than a galling bit of smuggery like, “Your father’s gone to a better place.” Lying in state, Jack’s mouth looked uncharacteristically stern. A funeral director’s son told me they have to glue mouths shut or else they’d just gape open, as they do in the immediate wake of death. But it was still recognizably him and I was grateful for the opportunity to take numerous long last looks. Our kids slipped mementoes and pictures into his pockets to take with him into eternity. I slipped him a pre-publication copy of the memorial piece I’d written about his life. Leaning close to his ear (all my life he’d been hard of hearing) the last four words I said to him were, “Thank you for everything.” Lesson learned: Whenever it’s feasible, go with an open casket. People need to see and touch and talk to the dead. Originally my three brothers and I were going to collect Mom from the nursing home and be with her through the funeral service until the nurse who knows her best cautioned us against it. It would just be pointless cruelty, she said. She told us she’d watched over as four different, infinitely well-meaning people had told Mom that Jack was dead and each time it was a heart-breaking thunderbolt of the worst possible news that left her sobbing and disoriented and then, within just a few minutes, evaporated completely. Her Alzheimer’s is now so advanced that she will never take on the fact of Jack’s death in any lasting way. Every time we visit her now, she asks if we’ve been to see Dad. I’ll say, “Not too recently,” and she’ll often reply, “Well, he was just here. I’m sorry you missed him.” Lesson learned: For my mother, Jack will never die and in some small but surprisingly pleasant way, that keeps him around for me too. I met an old friend in town a few days after the funeral and when I told him Jack had died at the age of eighty-nine, he said he was sorry but his face betrayed a flashing hint of incredulity and envy. I wondered at first, could I have seen that right? And then I remembered that he’d lost his dad when he was only fourteen. Shaking my hand, he said, “Let me be the only person to look you in the eye all week and say, ‘You lucky dog’.” I agreed he had a point. I remembered a medical scare back in the summer of 1988 when we thought Jack might buy the farm and I was so terrifyingly unready to see him go. Fifteen years later, that prospect wasn’t so appalling. Lesson learned: Time can make everything relative, including the desolation of losing your closest relatives. My father was not a religious man, and certainly not a Catholic, so I was deeply touched when Father Steve at St. Peter’s, quite unbidden, inserted Jack’s name onto the list of prayers for the dead at that Sunday’s mass. It so happened, I was booked to read those prayers at the 7:30 p.m. service and was able to do so in a clear and steady voice. Though taken all in all, I know my father to have been a good and kind-hearted man, I enjoy no complacent certainties about where his soul currently resides. Lesson learned: I will miss my father until the day I die and nothing that I can do brings him closer to me now than praying for him. – December 2003 IT IS REPORTED THAT my paternal grandfather upon first setting eyes on my brother Ted as he cooed and drooled in his swaddling clothes, sadly shook his head from side to side and intoned the words, “Poor little bugger.” It is not that Ted was a particularly homely or sickly wee bairn. On the contrary, Ted was a stunningly handsome and sturdy little unit. What kept my mother from scratching out the old man’s eyes at such a rude greeting for her latest offspring, was the recognition that Ernie’s dour blessing said much more about him than her new son. Ernie had reached a late and rueful period in his life when his well-nursed regrets greatly outnumbered his joys. More to be pitied than heeded, Ernie had become constitutionally incapable of taking delight or encouragement from anything much that life had to offer. And so, I’m sorry to relate, it continued unto the grave. I remember Ernie’s dearth of good cheer each Christmas when killjoys and mopes of every stripe step forth to take shots at this rude and giddy season that so offends and upsets them. Okay, maybe you don’t accept the Christian creed and you don’t believe that with the birth of Christ, God Himself came down to Earth to help all people win salvation. You’re hardly alone in your lack of belief. But aside from all that, how can you take umbrage at the idea of a special time set aside each year when people do everything they can to be welcoming and kind to one another? Charles Dickens was undoubtedly a literary genius of the first order but it doesn’t take a thing away from his reputation to point out that while he did create the character of Ebenezer Scrooge, he did not invent the human archetype on which Scrooge is based. Scrooge is legion and every year in a hundred different guises he hectors Christmas celebrants for their foolish and hypocritical ways. Are people spending too much money on inessential frills and amusements? Are they eating too much rich food? Are they listening to beloved old carols and feeling sentimental about relatives and friends? How dare they? I have far more sympathy for those who don’t lash out at other people’s celebrations but instead quietly retreat from the field of Christmas and draw the curtains. Often grieving the loss of loved ones, for a while at least these poor souls are emotionally incapable of partaking in any festivities that will only invoke memories of earlier, happier Christmases. Passing through this first anniversary of my father’s death last December, I too have been sabotaged by some of the traditional Christmas touchstones. A couple weeks ago I was caught completely off guard by the opening strains of Handel’s Messiah. Why was I crying? Oh right, we played that at the funeral home. After dinner last night, I almost lost it when my daughter recalled Jack’s usual form of farewell – “Bye now.” It is, I suppose, short for, “Bye for now,” carrying with it the suggestion (and the great Christian hope) that I will meet my father again some day. Seeing I was affected, my daughter demurred, saying, “Maybe we should be talking about happier, Christmassy things.” “No,” I told her. “Sad Christmassy things are good too.” I would even go so far as to say that without a definite note of sadness somewhere along the way, Christmas can ring a little hollow. Why is there such a poignant fall in the notes of so many of the carols I love best – In The Bleak Midwinter; O Come, O Come Emmanuel; Once In Royal David’s City? They all celebrate the birth of Christ but also acknowledge the tremendous sadness of what He would endure for our sake. And all of us must endure sadness as well because, just like Christ, we are born of flesh and are here for too short a time. Ernie had it half right. Life is indeed a hard slog that’s guaranteed to break your heart. But it also happens to be a miracle. It’s okay to say, “Poor little bugger,” to new-born babies so long as you also say, “And I’m so glad you’re here.” – December 2004 LIKE THE HALEY JOEL OSMENT character in The Sixth Sense, I see dead people. Without fail the dead start passing before my gaze in the first weeks and months following their funeral. I’ll be walking along some downtown street, or I’m parked on a bench or standing at a window half consciously perusing the passing scene when I’ll suddenly glimpse, almost always from behind, the spitting image of the recently departed. It usually takes just a few seconds for the illusion to fall apart. The subject will suddenly turn and the profile of their face is all wrong. On closer examination I’ll realize the person they remind me of would never have been caught dead (or alive) wearing that particular garment. While there’s something a little alarming about these apparitions, they can also be strangely consoling. Just for a blessed second or two these visions seem to rend, or at least thin out, the impenetrable veil that separates the living from those we wish were still here. My youngest daughter is the only person I know who experiences these visitations as frequently as me and we are agreed about the one great disappointment of our condition. We don’t see the really important dead people nearly as often as we would like. Her grandpa, my dad, has made himself much too scarce since his death nineteen months ago. She’s only seen him once buying cheese one winter afternoon at the Covent Garden Market - probably a brick of his beloved Stilton that would stink out the joint like Ben Johnson’s feet after a thirty-mile run. Until this week my only sighting was thirteen days after he’d died, lacing up his shoes a few lanes over at a Boxing Day bowling tournament at Fleetway 40. One of my brother’s friends came to my side to see what I was staring at and had to admit, “Wow, that does look like him, doesn’t it?” So imagine my famished delight when earlier this week I glanced up from the book I was reading in a Richmond Row café to suddenly see Jack walking by in white shorts and knee socks that exposed a good portion of his bony, phosphorescent legs. I immediately went over to the window to watch his progress for as long as I could, inevitably starting to discern those few details that weren’t quite right. This gentleman’s gait was a little too steady. The snow-white hair was precisely the right shade but its weave was too thick. And he was engaged in the kind of easy-going, two-way conversation with his companion that Jack’s bad hearing made impossible. But it was great to see him again and I returned to my chair with grateful and sorrowful tears in my eyes. A certain poignancy was added to this latest sighting by the book I was reading, the first volume of C.S. Lewis’ Collected Letters. Subtitled Family Letters, this volume documents Lewis’ protracted coming of age as he was supported to a major extent by his father while studying at Oxford University and making his first tentative forays as a writer. He was well into his 30s before he landed the first academic jobs that finally enabled him to support himself entirely by his own efforts. It’s a little disconcerting to see a man as famously honest and fair as Lewis, sniping about his old man to the extent that he does in these letters – particularly in those to his brother, Warnie, and his old childhood friend, Arthur Greeves. This disconcerts not just because it seems so ungrateful but because one recognizes the universality of the behaviour. Somewhere in the maturing process, all of us have this need, for a while at least, overtly or not, to distance ourselves from those who have literally given us everything, including life itself. Occasionally Lewis twigs to the fact that what bugs him about his father is, in fact, what bugs him about himself, but there was no full reconciliation before his father died. I, thankfully, have not been left with the sort of regrets that haunted Lewis for the rest of his life. Impossible as it may be, I’m always thrilled to see Jack. – August 2005 (A greater Jack sighting than both of these occurred about three months later as I returned from a trip to Italy and Britain in mid-November. The flight home from London, England stopped over in Swansea, Wales to pick up a few more passengers. Already all a-tingle just to have touched down however briefly in the land of Jack’s birth and boyhood, I ascended into rapture mode when Jack, sporting the jaunty grey cloth cap of his retirement years, led a party of five embarking passengers and took his seat about ten rows in front of me on the other side of the plane. I knew if I moved any closer, the illusion would fall apart, so I stayed where I was and communed with his spirit as we travelled back to Canada together.)

2 Comments

David Warren

7/12/2020 01:35:36 pm

Herman, turning to your Causeries du lundi, from burial in "the news," I am vividly reminded of the difference between a writer, & a journalist (or other piece of shit). The former describes an evanescent situation, in a more permanent way; the latter just reports facts, inevitably falsely, even in the rare moments when he is trying to get them right.

Reply

Barry Wells

9/12/2020 10:12:39 am

The best sighting of my late mother, Darlene, was more "paranormal" in nature and happened two months after she died in April 2011 at University Hospital's Intensive Care Unit.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed