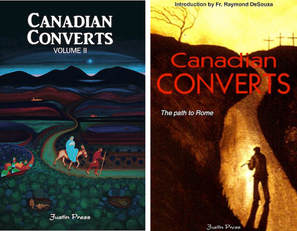

LONDON, ONTARIO - Delayed by a rotating pre-Christmas strike strategically timed to dampen what little confidence Canadians retain in their loathsome national mail service, those sadists at Canada Post just took three maddening weeks to deliver a much-anticipated package from north-eastern to south-western Ontario. Which is to say I finally got my mitts on my very own copy of Canadian Converts Volume II from Justin Press in Ottawa. It is a long-observed fact that I get a little antsy whenever I know that that any sort of book which I’m longing to read is inching its way toward me. And this reaction is at the very least doubled if it’s a book I wrote or, as is the case here, is a compendium which includes a contribution of mine. One of the central laws of what passes for literary culture in our times is that one is not allowed to review one’s own book. So I won’t be so gauche as to do that. But perhaps I’ll be allowed to talk around it a bit.

Perhaps the most effective way to do that is to first share with you my review of the first volume of Canadian Converts which appeared in Catholic Insight magazine (now, alas, defunct) in January of 2010: RELEASED LATE LAST YEAR from Justin Press, a new Catholic publisher based in Ottawa, is Canadian Converts, featuring first-person essays from 11 disparate and eloquent Canadians, recounting their own religious searches which all have culminated in the Roman Catholic Church. I have read a number of such essay collections before and few of them can match this one, both for the erudition of writing on display and the wide span of backgrounds in the writers themselves. Included herein are the religious confessions of currently incarcerated newspaper magnate Conrad Black; the founding editors of two remarkable magazines, the late Fr. Richard John Neuhaus of First Things, and the still-living David Warren who founded the now defunct Idler and today pens a widely read column for The Ottawa Citizen; Fr. Jonathan Robinson, the founder and superior of Toronto’s Oratory of St. Philip Neri; Jasbir Singh, a child of Sikh immigrants whose search for ultimate meaning and truth was greatly intensified when he narrowly escaped death in a Japanese earthquake; Amy Lau, a mother of five who has a master of science in biochemistry; Ian Hunter, a biographer, essayist and lawyer whose greatest spur and obstacle to conversion was the example of his devoutly Christian father who also happened to be fervently anti-Catholic; Kathy Clark, a Jewish-born daughter of a Holocaust survivor who went on to mother six children of her own and writes children’s books about her family’s struggles in Communist Hungary; Douglas Farrow, a theological author and professor of Religious Thought at McGill University; Eric Nicolai, an Opus Dei priest and high school chaplain who was primarily led to the faith by the compelling example of a childhood friend of unaffected Catholic piety; and Lars Troide, a professor of English Literature and a Horace Walpole scholar whose abiding moral sense drove him on from one pleasant-enough denomination to another until he found a church that cared more for eternal truth than fleeting subjective feelings. Considering that five of the eleven writers here considered hailed from the Anglican Church, one can appreciate the astuteness of Pope Benedict’s special invitation to disaffected Anglicans to ease their conversion to Rome. And observing that the second greatest number of these writers – three – came via the Lutheran Church, one wonders if the Bavarian-born Benedict, hailing from that region of Christendom’s first great schism, will be able to resist directing his next overture to the church that bears the foremost Protestant’s name. As a convert myself, I’m always interested to see how others managed to grope their way along the path to Rome. Though our destination may be the same, as this collection attests, there is tremendous disparity of approach. There are no generalizations that hold up for all, but it’s interesting to observe how often it is a believer’s less-utilized faculty that convinces them to make the leap of faith – the intellectual whose rational and methodical approach is blown to smithereens by a mystical experience; the constant reader who becomes convinced not by a well-formulated argument but by coming across the mute and inexplicable glory of a radiant sunflower; the person who’s frankly never given much thought to what they believe until they hear a startling assertion of faith that they can’t stop pondering. Recalling those earlier collections of conversion stories I’ve read, I recognize that all of them hailed from Britain or the United States, which would seem to validate the publisher’s claim that this is the first such collection in Canadian literature. There is a bit of a truism which maintains that the appeal of conversion stories to lifelong Catholics is that the convert takes nothing for granted and that it is salutary for all believers to be reminded of the compelling and logical appeal that the faith makes to a sincerely questing heart and mind. Wanting to ring a fresh variation on this sort of essay collection, in 1954 publisher Frank Sheed gathered short memoirs from lifelong communicants in a book he entitled Born Catholics, and sure enough, it wasn’t one of Sheed & Ward’s better-selling titles. While those accounts may have lacked the excitement of taking a journey from one spiritual destination to another, it would be a mistake to claim that only converts really think about their faith or know the truths they uphold more thoroughly than those who were born into the Church. It may be harder to convey the richness of the born Catholic’s religious experiences in a snappy personal essay but it seems to me that the most devout of these exude a confidence and a surety that a convert rarely knows. I don’t have any sort of documentation to back this up but I’m pretty sure that once we get past St. Peter and his first few successors, lots of converts become priests and nuns and even saints but very few of them have ever been elevated to the Papacy. As a ‘cradle Catholic’ Fr. Raymond DeSouza was not eligible to contribute an essay to this book, so instead he wrote the introduction, explaining these tales’ appeal to one who has “never doubted the truths taught by the Catholic Church.” Not the least of these points of appeal he says, is, “There is encouragement that despite all the manifest troubles here and there in the Catholic Church, she still attracts those seeking Jesus Christ.” NOSTALGIA'S TELESCOPE surely is contracting when a book review from nine years ago can leave you pining for a lost world. Oh, for a Church that appeared to only be beset by “troubles here and there” and wasn’t yet fixed in the public imagination as riddled with rot; that was headed up by a thoughtful and scholarly Pope who fought to uphold sacred tradition instead of a glib-talking virtue signaler with a shallow agenda who seems to see his primary mission as conforming the Church to a fallen world. That earlier volume had the good fortune to arrive four years before the commencement of our current dark age and served as a popular calling card for a worthy new publishing venture. Today one suspects that such a book of Catholic encouragement – which is what Canadian Converts Volume II most decidedly and defiantly is - is more likely to be greeted (when it isn’t just ignored) with a far greater measure of incredulity and scorn. I’ve promised not to review this anthology of essays by Kenton Biffert, Gregory Bloomquist, Fr. Martin Carter, Jane Craig, Anna Eastland, Fr. Doug Hayman, Graeme Hunter, Philip Prins, Fr. Hezuk Shroff, Sze Wan Sit, Ryan N.S. Topping, Benjamin Turland, Jason West, Queenie Yu and myself, but allow me a few general observations. One is the continued effectiveness of my favourite author of all time, G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936) as a uniquely persuasive shepherd when it comes to ushering people toward the Catholic Church. He pops up again and again in these recollections as, what Bishop Robert Barron calls, a “pivotal player’; a writer with an uncanny gift for formulating ancient truths with such power that they can no longer be resisted. I also note - as in the first volume - the continuing prodigality of the liberalizing drift of an increasingly deserted Anglican Church in generating new converts to Catholicism. A third observation would be to underline what Msgr. Kevin Beach writes in his introduction; a note which is far more pronounced in this second volume: “One element of these conversion stories that was unexpected – for me – was how, in many cases, the story was a joint adventure: that of husband and wife. It is our Catholic faith that the bond of marriage is a vocation from God. The spouses are to minister to each other the grace of the sacrament and, with this particular grace, to grow in holiness. It should not be surprising, therefore, that spouses would not only know the interior life of the other but share that life to its fullest, including a new life in the Church.” And finally, I would just point out how many times the writers here invoke the concept of “home” when talking about finally making their way to Rome. One third of the fifteen memoirists – including me – set the word into their essays’ titles. In explaining his early attraction to the Eastern Orthodox Church, Ryan N.S. Topping cites the primary appeal of other denominations: “It might as well be admitted. For most of us in the West, the East remains innocent. Unlike Roman Catholics, the Orthodox have no inquisitions, no crusades, no nasty priest scandals, and above all these things, a beautiful liturgy.” The history of Christianity is replete with instances when the appeal of making a clean break with earlier forms of worship becomes irresistible and a whole new church gets set up on what is perceived to be more adaptable and responsive foundations. It can seem like a great idea, a tremendous relief, to not be loaded down with all that dead history and unnecessary baggage, all that maddening connectivity to the place where it all began. But the unseen hook which ultimately captured the fifteen essayists in this book, is that as wildly dysfunctional as the Roman Catholic Church may be from time to time, her history is anything but dead, a lot of her attendant baggage is packed with meaning and beauty, and she also happens to be our home. Canadian Converts Volume II: Justin Press, Ottawa, Canada

1 Comment

Susan Cassan

27/11/2018 07:13:01 am

I look forward to reading your contribution to this new book!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed