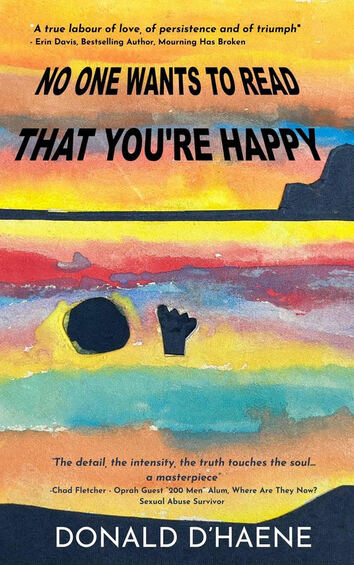

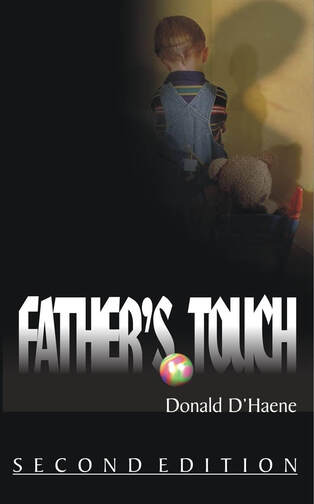

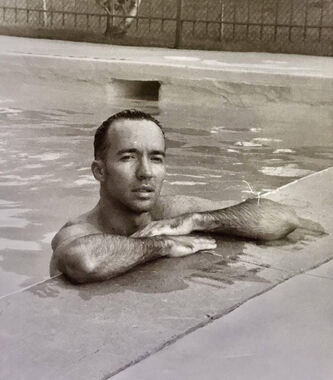

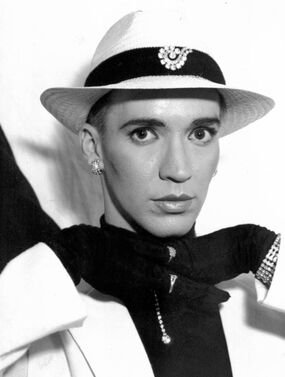

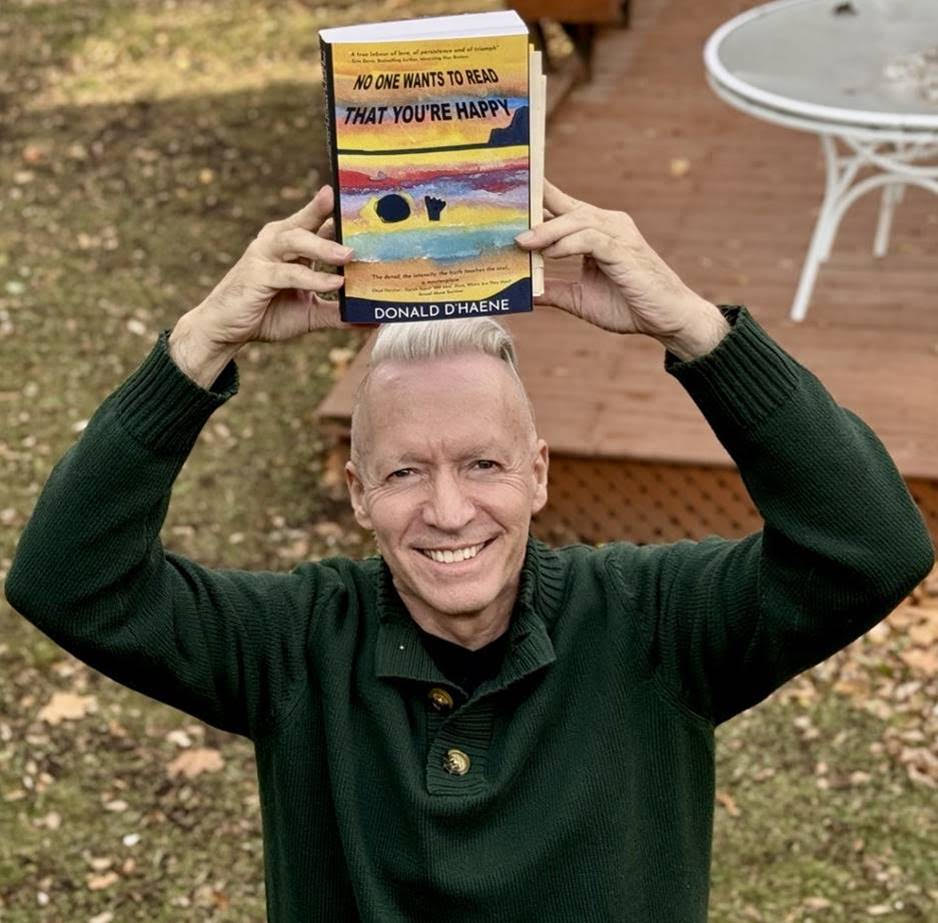

LONDON, ONTARIO – The first time Donald D'Haene registered on my consciousness was around 1993 when I was editor of Scene and trying to work up some enthusiasm for that magazine's annual cover model contest. Like a lot of fellows, I've always been indifferent to what strikes me as the higher neurosis of high fashion. Hemlines could go up or down or straight to Hell for all I cared. I shouldn't have been on the committee to choose that year's winner, because, frankly, I didn't understand the underlying premise of the contest. The big prize was a makeover, followed by a professional photo shoot. This struck me as a kind of madness. Having just chosen the best-looking girl out of a pile of photos and CVs, we'd then pass her off to a small army of beauticians, stylists and consultants, who'd work her over until she looked like someone else. Where was the sense in that? "Maybe we should be choosing the homeliest girl," I helpfully suggested. "Someone who could actually use a few pointers in improving her appearance." This was met with stony silence. Then Donald D'Haene's rather unconventional submission landed on my desk. He'd included one photo of himself as a very striking looking man with water-slicked hair and well-muscled arms resting on the rim of a swimming pool as he pensively surveyed the far horizon. In the second picture he was quite elegantly decked out like a 1940s cover girl in a white tailored jacket with matching hat, black gloves, lip gloss and earrings. What larks a guy like this would have with a makeover, I thought. Whether he came out looking like Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca or Burt Lancaster in From Here to Eternity (or even, perchance, The Swimmer) you knew he’d pull it off with serious panache. Though I was alone in choosing D'Haene the winner of our contest, I made sure we ran his photos in the next issue and gave him an honorable mention. From that encounter, I deduced that D'Haene was a remarkably open, funny and confident young man; utterly comfortable with who he was and more than willing to have some fun with his image. So I was surprised a few years after I’d left Scene and he was holding down a regular column there, when he responded to a Free Press column of mine in tones that struck me as humorless and shrill. In my offending column I'd skeptically examined a purported case of sexual assault at Western University where the female "victim" had gone out at 2 a.m. with a former boyfriend with whom she'd previously been intimate, had invited him back to her apartment where they necked and removed several articles of clothing and then – totally shocking, I know - the boy forced himself on her while she supposedly believed that she was only getting a backrub. I certainly acknowledged that the boy was a lout and was wrong to ignore the girl's protestations, but insisted the blame for what I called this "unconscious collision," rather than a "sexual assault," was at least somewhat mutual. D'Haene was having none of that, insisting females were always in the right in such cases and that it didn't matter how far things had progressed by mutual consent. The very second the girl didn't feel like it anymore, the sexual episode must cease. Certainly his argument was correct, both legally and morally. But D’Haene’s blank refusal to apportion even a trace of complicity to the girl’s erratic messaging struck me as one more dose of infantile feminist codswallop. (Quite literally, this seemed to be a case of ‘FAFO’ as website commentators like to say nowadays.) I was astonished that so reasonable and affable a man would so feverishly subscribe to such a stilted view of human responsibility. Well, in 2002 I learned precisely when and where and how D’Haene developed his overwrought sense of boundaries. He asked if I would read the galley proofs of his first book and give him some feedback. Knowing nothing of his back story and the notoriety his family had achieved twenty years before, I had no idea what to expect. Father's Touch, was a wrenchingly powerful memoir of a desecrated childhood in a perfectly horrible home where his father – a Belgian immigrant and a mainstay in Aylmer’s Jehovah’s Witness church - habitually forced himself sexually on three of his four children; two sons and a daughter. A third son, the youngest child, certainly knew that some kind of wickedness stalked that household but was spared the worst of these violations by the vigilance of his older siblings who took heroic care to – sometimes sacrificially - keep their baby brother out of their father’s range. This appalling betrayal and torture dragged on for well over a decade, starting before Donald had any idea what was going on and not stopping until he was in the thick of a torturously confused and isolated adolescence when he started to fight back. That drive for justice culminated in a very public 1982 trial launched by Donald and his sister against their father. Yeah, I had to admit; I got it now. That kind of childhood might make a person pretty obstreperous when it came to calling out the advances of pushy lechers on campus. By all rights, that first book should have been unrelievedly grim and certainly there were bits that made this reader feel sick at heart. But a large part of what made Father's Touch such a compelling read was not just the courage but the decency which D’Haene maintained as he pushed back against the tyranny of his father and strove to pull his other family members free of the soul-warping wreckage of their home of origin. There was a particularly striking point toward the end of that book - which concluded with the old man’s conviction and a farcically light sentence of two years incarceration with a possibility of parole in eight months - when D’Haene described staring at his father's mugshot and actually feeling a measure of pity for the sadness and shock in that stupefied face. If only that twisted brute had been fractionally capable of extending the same sort of compassion to his innocent children.  Father’s Touch was published twenty years after the conclusion of that trial and – as worthy as I deemed that book to be - I must admit that I privately wondered why D’Haene was willing to go digging through all that trauma again in such a public way. Hadn’t he endured enough gawking scrutiny in 1982 when the story of his family’s implosion made all the local papers and newscasts? It’s a tragic thing to acknowledge but the human instinct to sympathize with and support innocent victims can be not-so-subtly diminished when a case of incest comes to light. In the wake of this most taboo of crimes, an abiding stink seems to adhere, not just to the perpetrator but - to a much lesser degree, of course - the victim as well. That noxious aura impels an instinctive sort of recoil – as from a leper - that can make even well-meaning people hold back in disgust and embarrassment at their inability to imagine what could be done to repair such unspeakable damage. I didn’t voice these concerns for a couple of reasons. One was because I wasn’t at all sure that my questions didn’t constitute a kind of blaming of the victim. Who was I to counsel someone who’d endured such atrocities to pipe down about it? Wasn’t that just the sort of thing that an ass-covering rapist might say; or a hired flack for some corrupt institution that wanted their public relations problem to go away? If D’Haene’s approach to such things didn’t seem to be the one I would take, that hardly invalidated it. And with a little more reflection I realized that laying it all out for others to see, poring over the details one more time, discerning the patterns and devising strategies for getting a grip on this thing and moving forward . . . this was precisely my way of working out besetting conundrums in my own life as well. It’s what writers do. It’s the best shot we’ve got at processing setbacks and disappointments and finding a way to work ourselves clear of any attendant psychic or spiritual injury. In my uncertainty that the writing-cure could work that kind of purgatorial release for D’Haene, lurked the implicit admission that every problem I’d ever faced was bush league compared to what he’d endured. The misery that D’Haene was trying to work out – if it could be worked out at all – was of a whole different magnitude than anything I’d ever known. A little heartbreak here, the death of a loved one there, an occasional dream that went down in flames . . . Mine were pretty universal and easily relatable challenges to grapple with. And examining such struggles in a public forum was never going to leave me feeling like I was stamped in slime or doomed to upset all right-thinking members of society. But if D’Haene was willing to run such risks by publishing a frank account of childhood profaned by the very man who was honour-bound to protect and uphold him . . . if he could somehow summon the courage - the superhuman objectivity - to tell his story without succumbing all over again to the self-annihilating threat it posed . . . then I would suppress whatever feeble doubts I harboured and support his righteous cause. And now, twenty-one years after Father’s Touch, comes an equally up-close and personal sequel, No One Wants to Read that You’re Happy. The book’s title, we’re told, is ‘ironic’ and is a direct quote of D’Haene’s wonderfully anchoring partner, Maurice; spoken when Donald first announced that he was going to have to write another book. Was Maurice actually under any illusions that Donald had vanquished the nasty after-effects of Oedipal violation and now occupied some placid plateau of contentment? Hardly. But he’d been in D’Haene’s life long enough to know what that first book took out of him. And though he frankly wasn’t thrilled at the prospect of watching Donald submit to that anguish again, Maurice recognized that the refining, clarifying process of life-writing calls up a lot more than anguish – some of it strengthening and helpful - and that so much time had passed and so much had changed in the lives of all the D’Haenes, that it was time for an update and reappraisal. Far and away the most significant changes were the deaths of both parents (who both made a good age; one of them undeserved) and, most tragically, baby brother, Erik, who the other siblings tried so hard to protect and whose mental equilibrium and prospects were most thoroughly blighted by the chaos that reigned in their childhood home. The poor kid was fifteen years old when he first tried to kill himself, just a few weeks after his father’s trial and conviction. And the rest of his short life was regularly punctuated by terms served in mental hospitals, homeless shelters and even a prison, until his death a few years ago as a vagrant in Vancouver. Erik’s drawings and paintings – at once naïve yet boldly striking - are reproduced on the cover and throughout the book as are some poems and compositions and letters home, particularly those to his mother. Those letters typically expressed his love and his best religious intentions to start living right. But then when he did come home for a warmly (if warily) anticipated visit, more often than not, all of that beneficent striving and longing would somehow collapse in rancor and impatience and tears. This sequel to Father’s Touch shows us that some atrocities take a lifetime and more to work clear of and can still wreak havoc even when – or perhaps particularly when – the most immediate danger seems to have passed and caution is relaxed. Reading this detailed account of how D’Haene and his loved ones struggled with demons and messed-up reflexes as they tried to get on with their lives, is like watching a troupe of raw amateurs walk the high wire. Though cruelly limited in the steps they can take without precipitating a fall, again and again this reader was thrilled by the will and the courage – and, believe it or not, the humour - with which they set out on that daunting and wobbly trek of recovery. One could have forgiven the members of this horribly wounded family if they’d all retired to their separate corners in numbed relief to simmer in victimhood until the end of their days. But that clearly is not the D’Haene way. And gripped by some whack-a-doodle notion that it might not be too late to wrest a little meaning, beauty and love from lives that had been so wickedly disrupted, we watch them – sometimes working together in pretty chaotic concert, other times reaching inside their secret selves for eccentric strategies that wouldn’t pertain for anybody else – striving to move toward the healing light. Once their father was banished from their lives, it was Donald who stepped up to helm the family ship. Whip-smart and possessing instinctive literary gifts, he kissed any hope for university education goodbye and started up a cleaning business to provide himself and the remnant of his family regular employment and some kind of income. After reporting the depravity of their father to church authorities and being underwhelmed by the docility of their non-response, the oldest brother got out on his own early and largely made his own way. So it primarily fell to Donald to become a (sometimes resisted and resented) father figure to his two younger siblings. And it was Donald who personally navigated his uniquely unsophisticated but golden-hearted mother through the divorce court and usually lived with her, in her home or his, until the end of her life. Many people might be tempted to apportion some blame to Mrs. D’Haene for not stepping in between her out-of-control husband and her children. But she was so beaten down and controlled by him, so easily cowed and (it has to be said) so simple - and he was so deviously secretive and manipulative in when and where he abused his children – that taken all in all, she just isn’t held accountable in that way. Yes, she sometimes exasperated her children but they adored her. All through the manifold crises that rocked her household, Mrs. D’Haene soldiered on with her cooking and housework, pitched in with the family crew in cleaning office buildings and attended any sort of church function going, even when she wasn’t particularly welcomed there because of the notoriety of her family’s dysfunction. Donald often quotes entries from her diary which are remarkably unreflective. She keeps track of what everybody is up to but rarely ventures into the treacherous realm of deeper analysis. Donald clearly didn’t inherit his bold, risk-taking style from her. ‘And what became of the odious old man?’ you might wonder. Once Daniel D’Haene’s meagre prison sentence had been served, he made periodic raids on his ex-family’s attention via mail and phone calls and early on, even attempted surprise visits and ‘chance’ encounters. Though wildly disturbing, these overtures were all rebuffed or ignored and became a little less threatening once he moved to the Philippines, married four more times and even fathered more children. After Daniel converted to the Baptist Church, he started to blame the bad influence of the Jehovah’s Witnesses for any little mistakes he may have made in his earlier life. He read Father’s Touch and hated it and late in his life actually had the gall to fire off letters in which he hectored two of the children he’d sexually molested for putting their immortal souls at risk by becoming gay. If I ever land a gig as editor for an Illustrated Dictionary of Phraseology, I would seriously consider using a picture of Daniel D’Haene in the entry for ‘Piece of Work’. In his not-so bounteous spare time, Donald the family fixer has also been working on his own personal recovery for more than forty years now. He consulted three different therapists by the time he was twenty-four; eventually finding one who has worked with him, off and on, in a well-fitted way for decades; knowing when to press for more revelation and when to back off. A recurring feature in this book are fascinating transcriptions from those sessions. I recognize some of the same patterns of engagement in those dialogues from my own occasional conversations with Donald over the years; how some subjects on some days would just be deemed off limits; how baffling I found it when I’d run up against a too-pat dismissal of a subject that I knew he saw with more dimensions than that. But then, in his own time, on his own necessary terms, he might circle back to take it up again. While I’ve often been dismayed by Donald’s admiration for Oprah Winfrey – a woman I regard as an incontinent new-age gasbag – she deserves some credit for coincidentally facilitating one of the more riveting conversations in this book. Donald appeared on her show in 2010 as one constituent in a forum of two hundred men who had been sexually abused as children. Obviously most of the men didn’t get a chance to speak during the two-episode show which was just fine with Donald. He was there in solidarity with the other victims and while grateful that the subject was being aired publicly, he didn’t particularly want to contribute to a discussion in that forum. But he did exchange email addresses with one of the other participants as they were catching flights back to their respective homes. And in their rather extensive correspondence these two grown men - one heterosexual, one gay; both of them living with committed partners – have a free-ranging, compassionate and sometimes disruptively funny discussion about various processes and strategies they’ve employed to try to realign the mangled circuitry of their emotional and sexual responsiveness. There’s another conversational feature that turns up with some frequency in the book. This auxiliary character or voice is named ‘Other Donald’ and D’Haene identifies him as “the part of me that dissociated traumatic circumstances from my ongoing memory.” Similar manifestations of psychic bifurcation develop quite often among survivors of childhood sexual abuse as it grants them a measure of sanctuary from traumas that might otherwise imprison them. Donald is certain that he never could have become a writer without ‘Other Donald’s’ strict objectivity to help him – not to avoid but to negotiate - the many landmines that are strewn in his life’s path. And in the final exchange with his therapist in this book – a one-off, getting-caught-up sort of session, conducted via Zoom during the depths of our Covid lunacy - D’Haene reports the startling news that ‘Other Donald’ took what would appear to be a permanent hike following the death of his brother Erik. Without that old alter ego on the scene to keep things compartmentalized, Donald is all but swept away by fresh infusions of sorrow and survivor’s guilt, wondering if he couldn’t have done more to help Erik. While he’s appalled at how much time he spends crying, he doesn’t want to go back into therapy again but chooses to ride out this new situation on his own by writing out the full saga of his family drama and see what new perspectives that might bring him. And one thing that happens is that he and his surviving siblings draw together in heartbroken tears . . . and grow closer than they’ve ever been before. He steels himself up to set foot again in that church which meant so much to him as a child until it pushed him away . . . and is able to contemplate the possibility of some sort of reconciliation with the idea of faith in God. And in the concluding section of this book, Donald actually drops the line, “I have had both the unluckiest and luckiest life.” All of which makes me wonder if No One Wants to Read that You’re Happy should ultimately be regarded as an ironic title . . . though it’s certainly a misleading title for a book that I wanted to read very much and am glad that I did.

3 Comments

DouglasC

28/12/2023 09:15:56 am

With each new column I get more and more impressed by Gooden's writing. We are humbled by his treatment of his many subjects as hishumanity and insight shine through with every paragraph.

Reply

bill myles

30/12/2023 01:41:04 am

Shine on brightly now and in the year ti come!

Reply

Michael Prieur

2/1/2024 04:56:37 pm

Herman never ceases to amaze me at how he can verbally stick-handle through human experiences that defy a black and white categorization. HIs insights are truly inspiring, and his colorful prose makes one want to read it all. God bless you, Herman.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed