Illustration: Roger Baker Illustration: Roger Baker LONDON, ONTARIO – Seventeen year-old Nigel Mawson was drifting his way through an unrealized summer; struggling to find ways to pass the time in the ghost town that his daily life had become. He’d never experienced so barren a summer. Where had everybody gone? He was the only kid left at home as his older brothers had landed jobs as a groundskeeper and a busboy at the same Northern Ontario lodge. And all of his friends who mattered the most – no longer content to just hang out at the pool or devote entire weeks to Monopoly tournaments or loafing and spinning records – had shrewdly planned ahead to acquire semi-serious seasonal jobs. The McKenzie twins were working for their old man’s contracting company. Also working a family connection, Brian had found a slot on a property surveyor’s crew. Little Loss was harvesting tobacco on a farm near Delhi; a job he picked up from the notice board at the Manpower office downtown. And – in the only one of his friends’ jobs that actually stirred a little envy – an English teacher’s tip-off led Stu to a go-fer’s position with a government-funded film unit that was making a documentary about urban planning. It was like all of his friends had simultaneously figured out that something more was now required of them occupationally; that a paper route or a lawn-mowing gig with a handful of neighbourhood widows didn’t cut it anymore.

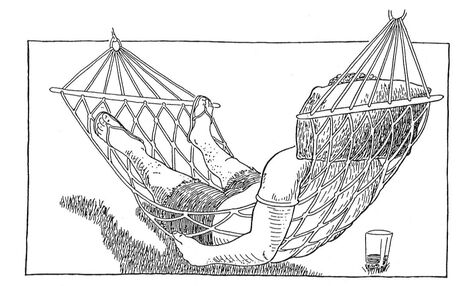

With a pang of shame Nigel recalled that he’d actually been invited in on a couple of these schemes when they were first being hatched. But, lacking the gift for visualizing summer in February, he’d shown so little interest that he effectively wrote himself out of their plans. When everybody hauled themselves back for their final year of high school in September, his friends would have oodles of cash and some actual work experience to help them land their next jobs. All Nigel would have was this big bag of humid nothingness and a dim sense of guilt for letting an entire summer evaporate without a trace. These cool, rustling nights and blazing, buzzing days served only to torture him. It was agony to be up to so little in what he reckoned must be the physical prime of his life. He couldn’t even boast that he was reading a lot – which, technically, he was – because he was reading such mind-rotting crap. One late July afternoon, Nigel was lying in the backyard hammock, reading Rolling Stone magazine, drinking a watery batch of grape Kool-Aid and occasionally running his hand under his bum to feel the way that it poked through the nylon netting like a wad of chewed bubblegum being pressed through a strainer. He’d been doing this for an hour when his mother came out, lugging a heavy wicker basket full of wet laundry which she pegged to the lines of an aluminum carousel that was set up in the sunniest section of the lawn. She did not look up from her task to behold her youngest son or say hello. There was no need. She knew he was there. She’d been feeling his cumbersome presence all summer long and it annoyed her. It seemed to Nigel that whenever she did look at him anymore, she wore a distracted, almost coldly mathematical look that curdled his guts a little. When little children see this look, they know they’re about to be dropped off at the orphanage. A week before his parents unloaded it, she’d looked at their ’59 Pontiac that way – the family’s spare beater in which he’d largely learned how to drive – and said to Nigel’s father, “We really should get rid of that thing, honey. The upkeep’s costing more than it’s worth and it’s such an eyesore.” He knew it was an offense against nature to be lying on his back and reading about pop stars while his mother heaved a sopping bed spread up over the line. But offering to help her in this task which she had well in hand and required no assistance to execute, would only call more attention to his shameful idleness. Nigel wished she’d either go away or else turn around to scream at him, “You’re such a disgusting slug, I can’t believe it!” Setting the magazine down on his chest, Nigel closed his eyes and stayed perfectly still, thinking that it might diminish his mother’s disappointment if she thought he was asleep. No, it wouldn’t. That was retarded. Nigel suddenly wished he was sick; some disease so physically devastating that his mother would be encouraged by the fact that her precious, valiant boy was actually able to lie in the sun, drink Kool-Aid, read musical fantasies and take a tactile interest in his own ass. “Oh, Lord be praised; he might pull through this ordeal after all!” “Something’s out of control,” Nigel thought; but could think no further until his mother scooped up her empty basket and carried it back inside the house. Nigel sat up then, swinging his legs over the side of the hammock and feeling like an outlaw who’s crept out of the bushes after the posse has gone thundering by. Giving his head a little shake, he poured the last half glass of warm, grape-tinged water and ponderously swirled it between sips. He knew that the jobs left for the picking at this late stage were going to be awful but he suddenly didn’t care. Even pedaling a three hundred-pound bicycle for Dickie Dee ice cream would be better for his soul than pissing away one more day like this. The standoff had lasted six disheartening weeks but Nigel was finally ready to put his shoulder to the wheel. * “I don’t suppose you’ve got a chauffeur’s license?” asked the Manpower lady. “I do, actually,” said Nigel, fishing it out of his pocket and passing it over for her inspection. This certification was entirely due to Nigel’s marvelously benevolent gran whose Christmas and birthday gifts had always been rather eccentrically inspired (A Field Guide to North American Birds? Really?) and who ponied up the moolah as soon as they were eligible, so that all the Mawson boys could receive the most complete driver training courses going. “Well, this is a job we haven’t checked out yet,” she told him. “It just came in this morning.” She handed Nigel a card that read: “Wanted. Personal chauffeur. One day per week to various locations in southwestern Ontario. My car. Successful applicant will be paid $3.50 an hour plus necessary gas and meals. Applicant must be a congenial non-smoker. Contact Mr. Norris McKinley, Suite 12A, Richmond Hotel, London.” Okay, maybe Nigel grasped the concept of “necessary gas” but what a bizarre way to phrase it. “Sometimes these guys are a little funny,” the lady warned Nigel. “Funny, ha-ha,” she did not mean. * Mr. McKinley had been living at the Richmond Hotel for the last six months; ever since his wife’s divorce became finalized and she got possession of their house. He always referred to the divorce as “hers” and it was one of the first things Nigel heard about when he walked over from the Manpower office for his interview. Half a year after the fact, the divorce and all of its ruinous ramifications remained the single besetting reality of Norris’ life. “Like a sheep to the shears and they fleeced me clean,” was his summation of their settlement. “I wooed her and I won her in 1922. In the sight of God we were married and what the good Lord has put together, let no man pull asunder. You know what that means, do you? It means that judge had no business giving her that divorce and the two of ‘em will fry in Hell for what they’ve done to me.” Norris eyed Nigel intently, an expression on his wizened face implying that any fair-minded chap would rally over to his side, spit on the floor and righteously spout some blood-curdling oath about the deviousness of women and the corruption of justice. “Yeah, it sounds pretty awful, alright,” Nigel muttered; choking on that much of a concession but determined to straddle the yellow-streaked line between appeasement and unemployment. Only one year younger than the twentieth century, Norris was sixty-eight and looked even older – close to death, in fact – which lent an undeniable pathos to his plight. What an awful time to be setting out (or getting turfed out) to make his way in the world alone. How big a pill must he have been to drive Mrs. McKinley to that? Tall, very skinny and red, Norris’ eyes, nose and lips all seemed to bulge out of a face that was too insubstantial to support such hefty features. A set of mud-flap ears and thin stringy hair pasted straight back along the top and sides only accentuated his startling resemblance to an angry gargoyle. He needed to gain at least thirty pounds before Nigel could be with him and not feel the distracting tension of sitting too close to an elastic band that was being stretched and stretched and stretched. There was an air of determined gloom to suite 12A; as if it had been occupied for half a year by a man who’d decided that it bloody well shouldn’t look like home and wanted to constantly remind himself that he didn’t have a home in this world anymore and there was no point pretending any different. The tiny room offered but three crummy ways to pass the time of day. You could lay on the unmade bed and stare at the wallpapered ceiling with seams that bulged. You could peer through the one, rattly window at the ever yet never-changing scene of patrons walking into and stumbling out of Kelly’s Boogie Parlour on the other side of King Street. Or you could sit on a folding chair at a metal-framed card table and read a well-thumbed New Testament or sift through a stack of stained financial papers which were held in place, oddly enough, by a heavy glass ashtray full of stubbed-out Pall Malls. Nigel didn’t happen to smoke but Norris’ requirement that his chauffeur be an abstainer struck him as a tad hypocritical. Smokes for me but not for thee? What kind of control freak lays down a dictate like that? It took Nigel fifteen seconds to imaginatively exhaust the recreational possibilities of this squalid little room and about ten minutes to discover that poor old Norris McKinley could talk about his wife’s divorce for a week and still not get around to the job he’d come to discuss. “So are these business trips you’ll be wanting to make?” “Business?” asked Norris, surprised at the thought. “There’s no business for me, lad. Not anymore. It’s just a matter of getting out for a bit.” Reaching for his cane, he pushed himself up to a standing position, carefully spreading his feet apart to secure some ballast. “I’ve had a stroke and my whole right side here is like dead wood coming along for the ride. They won’t let me drive now and they’ve taken away my license. I can’t walk much more than a block before I’m wheezing like an old lady and fit to collapse. And my own son won’t take me out on these trips anymore because . . . mainly because he moved away. So it’s not so convenient for him as it used to be. The truth of it is, I get a little stir crazy. I’m hiring you to take me out of here from time to time. To take me far enough away that I can see a new view. So what kind of business is that?” After this survey of circumstantial and bodily decrepitude – and it was really just his right leg that was buggered up but even it was hardly “dead” – Norris sat back down on the bed, looking impatient and maybe a little embarrassed. Bitching about the treachery of his ex-wife was one thing but making himself out to be such a loser was something else and he didn’t like it at all. “So we’ll go tomorrow, lad,” he said, attempting to rejuvenate the discussion with brighter spirits and looking a little demented for the effort. “What do you say we go up to Bayfield and back? You come around about two o’clock. We’ll go over to the garage and get the car and be on our way. We’ll make an outing of it.” Nigel had anticipated that any sort of job was going to force him to get up a little earlier than had become his summertime custom. But a two p.m. departure would impose no adjustment to his slovenly schedule at all. And with the days already starting to shorten again, it seemed odd that anyone so eager to feast their eyes on new vistas wouldn’t want an earlier start. Perhaps this was another indication of Norris’ faltering stamina. Or maybe what he really wanted to see was one of those famous Lake Huron sunsets. * Norris wasted little time in establishing the day’s conversational obsession. He had explained all the idiosyncrasies of his Dodge’s behavior and designated where it was that he wanted to go first. Then, as they were passing the Arva flour mill a few miles outside of London, Norris turned to him with a look bearing traces of a strange sly pride and announced, “Doris was unfaithful to me, you know?” It was so completely off the wall that Nigel could only laugh. “Your names are Doris and Norris?” “Aye,” said Norris, impatient with what for him must have been a very old joke. “And the first time was with my best friend.” Nigel was about to tell him that it wasn’t his business and he really didn’t want to hear about it, when Norris slammed a boney fist down onto the dashboard. “By Jesus, they went crawling behind my back when I was laid up in the hospital with gall stones. And that was only the first time.” The look of pride had vanished and in its place was wet and crimson anger; his words pushed out through lips that were sloppy with the rage of the criminally aggrieved. “The thing I couldn’t get into my head was how regular they could be about it. How cold and fast. How bloody vicious.” Then Norris emitted an eerie high moan and, rubbing his hand across his face, started to sob. Feeling slightly sick, Nigel slowed down and pulled onto the shoulder of the road. He couldn’t bring himself to stop the car altogether because then he’d feel obliged to address his whimpering employer and he couldn’t think of a blessed thing to say. He’d only signed on as a chauffeur; not a grief counsellor. So he just kept puttering along in the gravel at five miles an hour. When a station wagon swiftly overtook them – loaded up with kiddies and beach equipment and more bright spirits than seemed humanly possible (and exhaling a single strain of Donovan’s Hurdy Gurdy Man as it passed) – Nigel imaginatively invaded their space and rode along with them in serene enjoyment until their car disappeared over the horizon. Still sniffling as he recovered his composure, Norris pulled out a Pall Mall and sparked it up with the dashboard lighter. Figuring nobody smokes while weeping, Nigel took this as a signal that the worst of Norris’ emotional storm was subsiding. It might be safe to speak now. “Mr. McKinley?” he asked. “Do you still want me to drive you today?” Norris looked up, startled by the question. Moisture was still shining on his cheeks but already his voice was strangely steady and full. “For certain,” he said. “We’re going to Bayfield.” “But you feel so rotten.” “It’s always rotten,” said Norris. “And it never stops. And if it won’t stop, then I won’t be stopping either. So let’s show a little speed and be getting on with it.” With a heavy heart, Nigel eased the car back onto the road and accelerated. He asked Norris what he used to do for a living, hoping to steer him into more placid conversational waters. It worked for about three minutes as Norris talked about the commercial printing shop he’d started up in Bayfield; and even crowed a little bit about how he’d cornered the market in customized calendars for local businesses to give out to their customers at Christmas time. But this quickly devolved into musings on the concept of gratitude; in particular, the well of gratitude which evil and lazy Doris had never felt for hard-working Norris, her loving benefactor. All rivers led to the same old swamp and Nigel threw in his paddle and just let Norris rattle on and on. By the time they were cruising down the main street of Lucan, Doris was fifty-four years old and playing off four different lovers in the space of just one summer. Nigel understood diddly-squat about the labyrinthine ways of romantic love; even among young people, let alone embittered senior citizens. But he was pretty sure that by about a person’s fifties, such disruptive passions should have dampened down a little. The man’s stories just seemed preposterous. And they were put across with such a sniveling meanness that Nigel couldn’t help thinking that even if she had perpetrated an indiscretion or two, Doris probably wasn’t the real villain in their marriage and was well off to be clear of him. Quite unexpectedly, Nigel thought of his parents and was suffused with a profound new respect for them. He knew he could be pretty dismissive of them sometimes. But God, how wonderfully sane they suddenly seemed. How kind and generous and full of hope. Norris could sense that he was losing the attention of his hired audience and pulled himself up over the rim of his self-pity to comment on this fact. “You’re not saying much, Nigel.” “Mr. McKinley, I told you, I’ve got no place listening to these stories.” “You don’t believe them, then?” “That’s hardly the point, sir. I don’t know you or your wife . . . your ex-wife. I don’t know what went on. It isn’t my business and there’s nothing I can do with this . . . information, if that’s what it actually is.” “You could at least give me your sympathy.” “And wh . . . what would that accomplish exactly?” “Then I wouldn’t be feeling so alone.” “But it’s not aloneness from me that you’re suffering from, sir. I’m just your non-smoking chauffeur.” “What . . . ? Do you want one of my cigarettes?” “No thank you, sir.” “I wasn’t offering you one,” he snapped. “I specifically stipulated that my driver be a non-smoker.” “I know that, sir. And that’s what I am.” “Then why on earth did you ask for one?” “I didn’t ask for one. It was just a little joke and . . . maybe I was hoping we might change the focus of our conversation . . . such as it is.” “So you see all this as something to joke about, do you? You’re right enough about that, lad. It isn’t aloneness from you that I’m suffering from. It’s Doris, sure enough – the woman who vowed to be true to me and wasn’t. And that being so, I do believe that it’s meet and just that I should suffer. And I also think it’s cruel of you to dismiss that suffering and make jokes about it. Good riddance to her and you both if you won’t believe the word of a Christian.” One would think that such an impasse would have the potential to shut down the topic for good. But Nigel was lucky to be granted even five minutes of sulking silence. Part of the problem which Nigel was only beginning to fully appreciate, was that this outing which Norris had claimed was an opportunity to see a “new view,” was actually a trip to the heart of Doris country and a very old view indeed. * “Pull over here, then,” said Norris, after he’d had Nigel drive west for six or seven miles down a gravel road south of Clinton that was surrounded by mostly cornfields and the occasional timber lot. “There’s a special place here I want to see again.” Through a narrow woods between two farms, Norris, a little shaky on his legs and cane, led the way down a crude but gently graded and slightly curving stairway made of cracked boards implanted in dark, hard earth. At the bottom was what Norris called a “glen”; a secluded oasis with a stream running through; a cool velvet pocket of the world so perfectly inviting that even the most impatient traveler would feel impelled to linger for a bit. Norris sat down on the second step from the bottom and Nigel, a few feet away, stretched out on a slope of ground covered in rusty brown pine needles. If Norris knew how to find places like this, he couldn’t be all bad, thought Nigel; gently squirming his spine against this shallow, natural mattress as his highway nerves came unknotted and his muscles drank deep refreshment. Grateful that Norris seemed content to just sit, Nigel lifted his eyes to the green boughs above him, heard the light swish of a breeze moving through and put his mind out to graze where it wished. Within twenty seconds, he was thinking about girls. Nigel had never been out on what could even be liberally defined as a date. No female (or male for that matter) had kissed him in over four years. Not even his mother. And yet Nigel sensed that the essential key to the meaning of the universe was embedded inside girls and could only be attained by – lovingly – wrestling it out of them. There were girls he was powerfully intrigued by. His attractions felt a bit like hypnosis in the way that they could take such ownership of his imagination. But he was held back from making definite overtures to any one of these girls by a nagging apprehensiveness that he chalked up to what he called the ‘dead puppy theory.’ Between the ages of four and eleven, Nigel had grown up in the gracious company of a basically fox terrier mutt named Lucy. For seven years just the two of them would often head out on extensive sniffing expeditions and during those exploratory rambles, had fused their not so very disparate temperaments into what sometimes felt like a single, six-legged organism. But their beautiful communion came to an end on a cursed Friday afternoon in January when Lucy was cruelly sacrificed to the gods of technology on Commissioners Road at rush hour. After several weeks of mourning which he felt as completely as only a young boy can, Nigel went to his mother and asked if it might be possible for them to get another dog. “Absolutely not,” she said, her tone suggesting that the very prospect filled her with dread. “Aw, please.” “No, Nigel.” “Why not?” His mother hesitated to give her appalling answer. But having no other to offer in its place, she did. “Because they die,” she said and exploded into frazzled tears. Well, that was one way of looking at it. Nigel deplored his mother’s fatalism but it wasn’t completely foreign to him. If you could measure such things by the volume of tears they produced, she and Nigel had been the ones who’d taken Lucy’s death the hardest. But even though he'd been ready to take on another dog while his mother was not, Nigel was aware of other kinds of commitment that he wasn’t so willing to make. And this self-protective wariness continued to the present day. The whole question of dating, for instance, was fraught with hesitation. If a girl ever did give him a chance, he dreaded that she might have second thoughts when she got to know him a little better. Or she might just spurn him altogether from the get-go. And he was leery of other aspirational ventures that made some appeal to him in the abstract – like really trying his hand as a musician or a writer or investigating whether religious belief was actually possible – but which carried no assurance of success and would leave him feeling pretty mediocre if they didn’t pan out. Something in his nature was always warning him that acting on one’s dreams might be a setup for disenchantment and defeat. God knows that the evidence was plentiful enough for taking a dim view of prospects. On his trips downtown he sometimes studied the faces of adults on the Oxford bus – most of them, he presumed, married and experienced in love, most of them employed and in some sense in control of their fate – and most of them looking like walking wounded. These things we held up as goals or ideals didn’t appear to be working out all that well for an awful lot of people. How could you survey so many dismal visages and still think that lasting love or personal fulfillment were real possibilities? It was enough to turn you into a conscientious objector; a seventeen year-old deadbeat and a hugger of hammocks. What must life be like for some? To wake up married to one of those sad pale hens who sat brooding their eggs on the work-a-day bus and hatching dull schemes of misery and disappointment? You wouldn’t want to rush into these things if it weren’t for the younger sisters and daughters of those poor stewing hens. There – for a moment at least – was beauty and enchantment. And Nigel would strap on his pair of wax wings and run like a demon for the edge of the cliff . . . and then screech to a halt before reaching the precipice; dissuaded from throwing himself into any tantalizing mysteries by those some three miserable words: “Because they die.” “So it was here that I asked her to be my wife.” Nigel looked over at Norris, wondering how it was possible that he’d almost forgotten him; almost dreamed him into oblivion. Norris seemed new to him and Nigel was interested. This was the kind of stuff he’d been longing to hear. “Had you been going out long?” “No, we were still wrapped up in what they call your first bloom. They say the later blooms are fed by deeper roots and I won’t deny it . . . but that first one . . .” Norris trailed off; his hands fluttering in small, inarticulate circles; reminding Nigel of that great line from Eliot’s Sweeney Agonistes: “I gotta use words when I talk to you.” “She was sitting about where I am now,” he continued. “I was standing out in front there. We’d been to the fair in London where we’d been just as invisible as lovers can be when they’re all wrapped up in themselves. Not a ride, not a game, not a single booth or exhibit . . . none of it held our attention. I knew it was the day and I knew that this must be the place and I brought her here in my father’s Ford. She didn’t hesitate. She knew what the wind was blowing and she was with me all the way. And that’s where the magic is. It’s that first knowing that what you want from her more than anything else you’ll ever want . . . well, she’s wanting the very same thing from you. And right there, everything grows twice as alive. How can a man or a woman ever forget?” Norris stopped talking then, just when Nigel actually wanted to hear more. But he sensed it was a silence that shouldn’t be probed by questions and he simply let it go and grow until it wasn’t silence anymore but was just the quiet way of things. After another five minutes, Norris looked up, realigning his back with a bit of a stretch, took a deep breath and asked, “Will you help me up, then?” “With pleasure, sir,” said Nigel, standing up and shaking pine needles from his pants and his hair; crossing over to stand before him and imparting his first genuine smile to the old man as he offered him his hand. Nigel was a little disappointed when Norris wouldn’t meet his eyes as he pulled him up onto his pins. He hoped the old man was preoccupied by some geriatric need to attain his balance or maybe nurse a sore joint. But no, that wasn’t it. When Norris spoke again, it wasn’t the gentler voice he’d been using in the glen. He was back to the highway death rattle: “Course, all that was before the devil got his hooks into her.” Nigel swelled with silent fury. He’d been about to help Norris up the stairs but suddenly couldn’t bear the thought of being near him. Nigel moved around and ahead of the old man, bounding up the hill and heading back toward the car; stomping and swearing under his breath every step of the way. “That stupid old fucker. It doesn’t make any difference to him. He can look at it this way, he can look at it that way. He just makes it up as he goes along, pisses all over his own dreams, and then expects me to fucking sympathize. Well, tough luck, Charlie.” Kicking the tires of Norris’ Dodge, Nigel heard a rasping sound and turned around to see Norris standing at the top of the stairs and looking down over the glen; making a big deal out of scraping the phlegm off his tonsils and launching a missile of spit. Nigel began a rapid march toward him and stopped about ten feet away; glared at the man and yelled, “Mr. McKinley, I do not get you at all. I mean what is this all about?” Norris lurched around to face him and bellowed in an animal voice, “The woman is a whore!” “Then move on with your life. Forget her.” “I can’t.” “Then forgive her.” “I can’t.” “Then rot in Hell.” “I am.” * They arrived in Bayfield in time for a late dinner at a rather nasty inn on the main drag where the man in charge of the dining room cum bar unenthusiastically greeted Norris by name and said he hadn’t seen him for a while. The host’s clipped manner frankly suggested he would’ve been fine if Norris’ absence had been extended indefinitely. Norris picked up one menu and handed it over to Nigel. He wouldn’t need one. “I’ll just have a 50 Ale,” he said. “Ah, your usual,” deadpanned the host as Norris led the way over to a corner table. Norris had barely uttered a word since their shouting match at the glen. And this decidedly chilly atmosphere continued through dinner as Norris drank three successive bottles of beer and Nigel picked away at his cardboard chips, watery coleslaw and breaded fish byproduct triangles with a glass of iced Coke on the side. It was uncanny how Nigel yearned for peace when the man was yammering and then longed for him to say something if he went too quiet. There was no winning with this guy. Watching Norris wordlessly pounding back beers on an empty stomach, Nigel feared that things could only be getting weirder and darker in that messed up mind of his. Perhaps he shouldn’t have told the old man to rot in Hell. Norris did, after all, have Christian pretensions and perhaps that sentiment could not be overlooked. A little desperate to get talking about something – and shuddering at the falsity of his supposedly casual tone – Nigel broke the silence by asking, “Where would you like to go next week, Mr. McKinley?” “Hmm?” “For our outing next week, where will we be going?” Provided Nigel made it back to London in one piece, he was determined to never go near the old coot again. But this was all he could think of to call him out of his glowering silence while also signaling that he respected him enough to honour their contract. Which he didn’t. And both of them knew it. “I don’t know that we’ll be going anywhere,” Norris said. “But won’t you want to get out and see “new views”?” “Who on earth do you think you’re fooling, Nigel?” For the first time in a couple of years, Nigel actually felt himself blush. “No one, I guess.” “You’re gripped by silly notions that aren’t becoming to a lad your age.” “Like what?” asked Nigel, ashamed of the whimpering note in his voice, then angry for constantly letting himself get wrong-footed by this tiresome, overbearing man. “Have you ever heard of rose-coloured glasses?” Norris asked. Nigel nodded that of course he had. “Well, I’d say that you’re sporting a pair that extends from the crown of your head to the tip of your chin. I only know this because I used to wear them too. That must be why it irritates me so much to see them on you. You might think it’s discretion . . . or a sense of honour . . . you might believe you’re hoping for the best . . . These are all things I used to use as filters for my rosy glasses. At different times, mind you, but that’s something we’ve shared. Does that upset you? That we’re that much alike? Your last name’s Mawson, right? Have you noticed? Our initials are even the same.” “Probably not our middle initials, though,” Nigel playfully interjected. “It doesn’t count if all three don’t match.” Norris ignored this ploy to distract him from his usual mania. “Look it, Nigel, you can take those glasses off now and start seeing for yourself. Or you can wait a few years and let some whore smash them while they’re still on your face. The second approach hurts a lot more, you can take my word. But either way, things aren’t half as pretty as you’re seeing them.” Okay, Nigel thought. No more finessing. He sees through it all anyway. “If I saw things your way, Mr. McKinley,” he said, “I don’t think I’d ever come out of the house.” “But that’s just it in a way, isn’t it, Nigel? You don’t come out of the house. I try to address you, man to man, about the things I’ve seen and known and you slip on your glasses. You puff up your chest like a self-righteous little bird and say, ‘No, no, Mr. McKinley, I won’t hear you say one bad word about this woman.’ But back in the glen, there were tender jewels in your eyes. ‘Yes, Mr. McKinley, tell me about the fair. Tell me about your wife with ribbons in her hair’. It’s almost laughable, Nigel.” Nope. That cheap shot did not find its target. Nigel knew that he was not the one strapped into a pair of distorting spectacles that prevented him from seeing the world as it is. Steeling himself up for a reaction he could not predict, Nigel asked, “Sir, where exactly does your faith come into all this?” The old man’s eyes subtly bulged out a little further than usual. Clearly, this wasn’t a question he’d anticipated. He didn’t have a ready answer and the line of his lips gave no clue as to what he was thinking or feeling. So Nigel dared to elaborate. “You keep talking about your Christianity but – to say the very least – you don’t seem very forgiving. I don’t think I’ve heard you once try to see the best in a person or a situation. Aren’t Christians supposed to do that?” Again came a considerable silence, first broken by one lie in the form of a sharp and utterly mirthless laugh. And this was followed by a second one: “No,” he said; again not meeting Nigel’s eyes. “In the face of directly contrary evidence, a Christian has no such duty.” Draining the last of his third bottle dry, Norris smacked it down on the table as a conversation closer. Nigel knew that the sudden sharp sound was supposed to make him jump or flinch. But curiously enough, it hadn’t. “There’s some people in town I want to see. Then we’ll go home,” Norris said. “People?” asked Nigel. “Aye. That’s right,” he said with a filthy gleam in his eye. “I don’t expect she’ll be alone.” Then, pushing himself up from the table before Nigel could ask another question, Norris hobbled off to the washroom to unload what he could of his liquid supper. Nigel could’ve gone too but his need wasn’t all that urgent. And right now there wasn’t much in this world that he wanted to do less than sidle up next to that crazed goat while each of them directed streams of urine into porcelain fixtures. He could do that with a friend or an innocuous stranger but not with someone who wished him ill or held him in contempt. Although it seemed that their appalling outing was about to take a turn for the worse, Nigel surprised himself by sitting back in his chair with what seemed to be a placating sense of calm. He knew he hadn’t reached home-free yet but for the first time all day, Nigel started to feel some confidence that he was going to get there. He still wanted very badly for this day to be done and to get beyond the range of this poisonous crank for good. But in some way that he couldn’t have explained, he knew that this waking nightmare was finally lifting; that Norris’ control over him – and his creepy knack for unnerving him – was starting to break down. * Outside the inn in the pale light of dusk, Nigel sniffed a slightly cooled air imbued with the always-thrilling smell of open water from just a couple of blocks away. What a waste it seemed, to be at the beach on such a fine evening and not be going for a swim . . . but instead to be retained on this wretched mission of post-marital harassment or whatever it was that Norris had planned. “So what happens now?” Nigel asked. “I drive you to your ex-wife’s house and we knock on her door or throw a brick through her window or something?” Norris did not care for the cut of this feistier Nigel’s jib. “Give me the keys,” he said. “I’ll be driving now.” This was a terrible idea and Nigel flatly rejected it with a shake of his head. “No, sir. You won’t. Your license has been revoked. Give me directions and I’ll take you there.” “It’s kind of complicated,” Norris said, making a slight move toward him. “It would be easier if I drove.” Nigel stood his ground with his hand in his pocket to guard the keys if necessary, though it seemed unlikely that Norris would be stupid enough to try to take them by force. “You’ll be driving back to London,” Norris assured him. “There’s no question of that. It’ll just be around the village. It’ll keep me in shape.” “And land you in jail. No way, sir.” “Listen, Nigel, it’s my damned car and I won’t be making a bloody scene of it. Now give me the keys.” “Forget it, Mr. McKinley. It’s not happening.” Nigel’s eyes were drawn a bit to the right of Norris’ ear where they met the eyes of a middle-aged man who was very deliberately coming up along the sidewalk behind Norris and in an act of bold familiarity, gently placed his hands on the old man’s shoulders. “Good call, kid,” this interloper commended in a voice which had the power to make Norris shrivel and squeeze his eyes shut in defeat. “Hello, Peter,” said Norris in a rueful voice, not turning around yet to face him. “Hi, Dad,” came the equally low-key response. So here was the son who Norris said had moved away and couldn’t serve as his chauffeur anymore. The blinds on the inn’s dining room window fluttered and Nigel saw their host of just a few minutes ago nod knowingly to Peter and then go back to his work. Norris saw him too. “It was Joe who let you know I was in town?” asked Norris. Peter stepped around to face his father. “Don’t be taking it out on him, Dad. Me and Mom have spies everywhere. You know you’re not supposed to be here.” “Can’t a man come and visit his own home town?” “No, not when he’s you. Not when Mom’s had a restraining order taken out against you.” “That order is predicated on nothing but lies,” said Norris in a considerably louder voice, starting to stoke his engine of self-righteousness and quickly regretting it. “Yeh, you know all about lies, don’t you, Dad?” asked Peter with some vehemence of his own. “I’ll bet your latest hired boy heard dozens of whoppers on the way up here about Doris the foul fornicator. And not one word about how you couldn’t keep it in your pants. Or how you . . . ?” Peter stopped himself mid-harangue and took a breath and turned to Nigel. “I don’t mean to drag you into this, kid. I know you just wanted some work and I’m sorry this is what . . . Did you get this job through Manpower?” Nigel nodded that he had. “Right. I’ll call them in the morning and make sure he’s taken off their listings. Again. I never seem to get the same person there twice. That’s the problem we’re having there. Now then, what time did you two head out today?” “Two o’clock,” said Nigel. “Was it $3.50 an hour again?” “That’s right.” “Okay, you’re not going to be getting back to London before about ten, so . . . Dad, give this kid thirty bucks and do it now or I swear I’m calling the cops.” Obviously resentful but not daring to refuse, Norris pulled out his billfold and extracted two twenties. “I don’t seem to have a ten,” he muttered. “Even better,” said Peter taking the bills and passing them over to Nigel while keeping his eyes fixed on Norris. “I’m sure he earned it.” Turning to Nigel again, Peter apologized for repeatedly calling him ‘kid’ and asked him his name, which he gave. “Okay, Nigel, if you could just get in the car, I need to talk to my dad for a few minutes. We won’t be long and then you can get going. And thank you for not letting him horse you around completely. I’d say you’ve held up pretty well. Some of his drivers have just been basket cases.” As Nigel slid into the driver’s seat, he heard Peter say, “Dad, I’m trying not to involve the cops here. Maybe I shouldn’t care but I kind of hate turning in my own father to the police. Now what are we . . .?” Their voices ceased as Nigel pulled the car door shut, and all he had to go by were the physical attitudes and gestures of the two men: This oddly likable son in an impossible situation, trying to honour whatever still could be honoured in this ruin of a man who’d given him life. And the obsessed and grotesquely wounded father, struggling to contain his boiling resentments so that he could hang onto some connection with the last person in the world who gave a rat’s ass about the hell his life had become. When Norris visibly crumbled into Peter’s arms, his boney shoulder blades rising and falling with each racking sob, Nigel smiled a little with pity for the pair of them and some blessed relief for himself. It was over. And he felt quite certain that it was going to be a quiet drive back to London. * His summer job having drawn to a close, Nigel was back in the hammock next day. He intended to stay there, maybe not until school started but for a good few days at least; thinking dark thoughts about men and women; how deep and weird their relations could go; how no one ever really knew what went on, sometimes not even the parties involved. On her knees in the dirt beneath their dining room window, his mother replaced a patch of straggly petunias with fresh chrysanthemums. And as a cicada sent forth one shimmering note, Nigel closed his eyes to the sun’s red glare and yawned in the face of disaster.

4 Comments

Jim Chapman

20/8/2022 12:23:19 pm

Lovely!

Reply

Mary Jo Jansenberger

20/8/2022 05:05:30 pm

Brilliant. Loved it

Reply

David Warren

20/8/2022 06:13:51 pm

Yer blog story this morning was remarkable & impressively distracting. Kept me glued, & I still feel the sticky this evening.

Reply

Jim Ross

22/8/2022 02:27:42 am

I just met Norris McKinley, past Thursday morning. You described him perfectly. Well done, Herman.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed