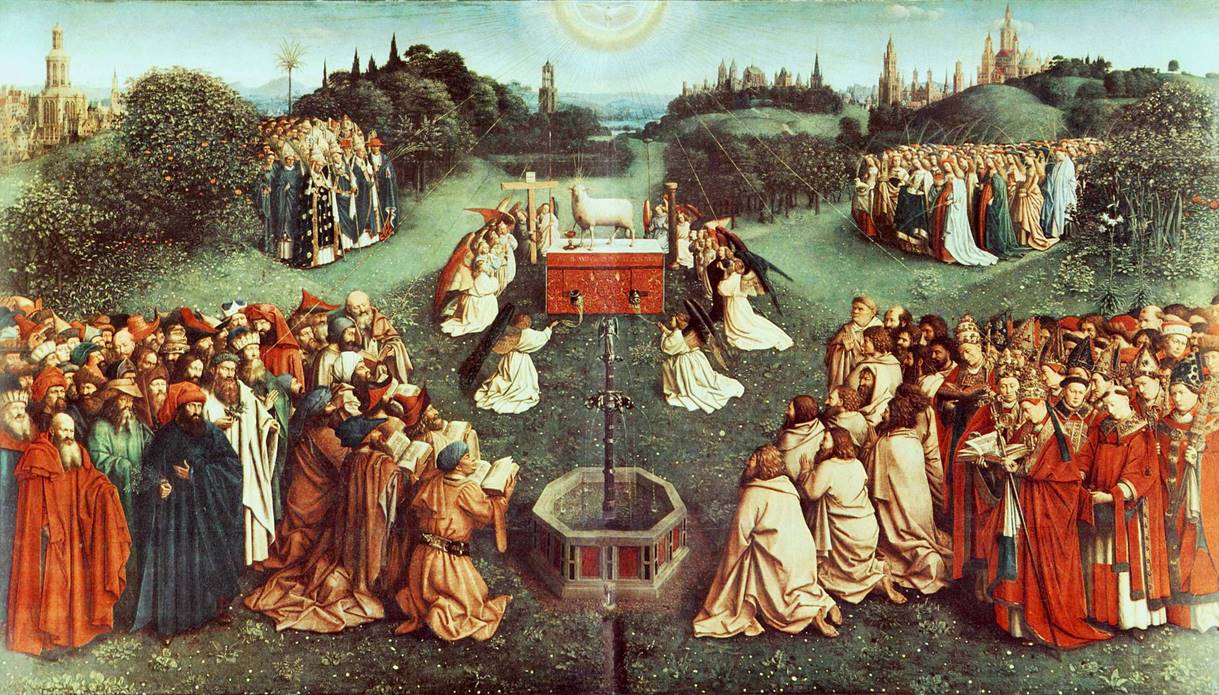

LONDON, ONTARIO – This Easter will mark the thirty-sixth anniversary of my conversion, baptism and confirmation into full membership in the Roman Catholic Church. Getting out my handy actuarial table I see that I have now spent the better part of my life as a Catholic. In one way, that feels about right. I know that this is the Church where I belong and I have felt that way from the moment Bishop Sherlock baptised me and anointed me with holy oils at the great Easter Vigil at St. Peter’s Cathedral on April 22, 1984. Yet in other ways – thirty-six years into this glorious game – I still feel like a callow newbie, hopelessly out of my depth in the company of those lifelong Catholics who live the life of the faith at its fullest. Intellectually, spiritually, aesthetically the Catholic tradition is so inexhaustibly rich that I often get a little panicky at how much material there is to catch up on before I’ll really feel that the proper imprimatur has been marked on my Catholic Operator’s Licence. I’ve done a pretty fair job of studying St. Augustine but even if I had the brain cells, will I ever have the time to do similar justice to St. Thomas Aquinas? I rarely meet anyone who’s read more of the lifetime output of Monsignor Ronald Knox, G.K. Chesterton or Dorothy Day but when it comes to a comprehensive knowledge of the literary remains of St. John Henry Newman, Jacques Maritain or Hilaire Belloc, I don’t feel quite so smug. So what in the world was it back in 1984, in the home stretch of the 20th century and the second millennium that drew a typically unconscious product of liberal modernism like me into the Roman Catholic fold? Biologically and historically, there was no accounting for it at all. My home town of London, Ontario in the southern-most peninsula of Canada was as stiflingly British a colonial outpost as John Bull’s great empire ever spawned. Our founding in 1793 even predates Queen Victoria and for most of our existence, the Anglican and British Protestant churches have been the denominations of social domination. Scrambling up the British trunk of my family tree to my Welsh and Irish parental limbs and into the tracery of Canadian twigs of which I am but one (and upon which the first two of my three children appeared as tightly furled buds when I came into the Church) I was faced with the same homogenous prospect wherever I looked. As far back as my forbears could trace, I was the product of two pretty wobbly Protestant strains that occasionally lapsed into agnostic indifference but were totally unmarked by the stamp of Rome or any sort of sustained enthusiasm. My father actually served a couple of terms as a church elder but he did so mostly at the behest of my mother who fitfully attended a Baptist Church as a child and continued that erratic adherence as an adult and a mother when, for a few months at a stretch, she would pack us all off to Calvary United Church in South London every Sunday morning and then for some mysterious reason – and with no objections raised by my father or my three older brothers and I – we’d suddenly drop it for a few months. In a similar, scattershot way, my three brothers had all been baptized shortly after their births and I was not. This wasn’t the result of some decision my mother came to. It just slipped her mind and by the time she noticed the oversight, I think she was a little flummoxed at just how she’d go about gracefully rectifying the lapse. Still, she enrolled me at a Vacation Bible School one summer which I didn’t absolutely hate and she sent me and my brothers to a Bible Class at a neighbour lady’s house for a full year and thanks to both of those experiences, I had a better grounding in Bible stories and Christian precepts than a lot of my friends. I know she considered herself a Christian all of her life and when I announced that I was becoming a Catholic, she was genuinely thrilled with the news and proudly sat with my Dad throughout the three hour Easter Vigil service. It was only at the time of her death on the - get a load of this - 25th anniversary of that 1984 Vigil that I fully appreciated the efforts she had made in her dear and scattered way to always keep God before my eyes. At her funeral service just before they closed the lid and wheeled her casket away for the last time, I impulsively dug the Rosary out of my pocket and laid it in the crook of her right arm. Though I sensed from my childhood that I was destined to become a Christian and would occasionally flit from church to church in search of that elusive form of service which would seem most magically congenial, it tells you a lot about the overwhelmingly WASP complexion of London that I was 31 years old before I ever attended a Catholic Mass. And five minutes after that service concluded - thrilled by simultaneous undercurrents of homecoming and embarking on a whole new adventure (rather like a wedding day, actually) - I signed up for instruction in the faith. In the years since I joined the Church, I’ve watched a good number of friends also make their way across the Tiber, sometimes coming from other denominations or from a state of religious dormancy, and have marvelled at how complicated and protracted the process can be; at least in comparison with my experience which seems to have been pretty straightforward. I didn’t even dig in my heels at some of the ‘caring and sharing’ fluffery of the Church’s RCIA (Roman Catholic Initiation for Adults) program. I made sure to augment it most weeks with a more rigorous one-on-one consultation with St. Peter’s rector, Fr. Jack Michon, but I was perfectly happy to go through all that introductory material as part of a large, general cohort. In my wife’s family, it was also her mother who felt an intermittent attraction to the Anglican Church; an interest that was regularly pushed aside by the distractions of day to day life and, more pointedly, by her husband’s sometimes virulent scepticism of all faiths but most particularly Catholicism. She at least had been baptized but as a young adult, questions of faith for my wife were a treacherous minefield whereas I was more open to persuasion. I read a lot of C.S. Lewis, G.K. Chesterton and Malcolm Muggeridge and was excited by what all these men had to say about Christ. I had conducted some experiments with prayer as a teenager and was alarmed when I started to sense that this wasn’t a one-way conversation; frightened because of the changes I knew I would have to make if I followed this any further. A few weeks before our wedding, during a rambling late night walk through snow-clogged streets which included a visit to the railway reclamation yard, I told my wife that I knew I had some unfinished business which, sooner or later, I was going to have to delve into further. “You might end up married to a Christian,” I warned her. She wasn’t thrilled by that announcement but it didn’t scare her off. There were plenty of signs and portents before I took that big leap. On one of our earliest dates I persuaded her to accompany me to a south London church to watch some full immersion baptisms and we looked at each other in startled amusement to hear a young woman gasp at the sudden coldness of the water. Another night we dropped into a Christian coffee-house in Grand Bend and got into a discussion with a young pastor about early Christians’ use of secret symbolism to signal their allegiance and the next day on the beach, she surprised both of us by idly twisting the stem of a leaf into the perfect outline of a fish. Though she couldn’t find a way to approach it herself, she had no animus against Christian faith. Still, six years into our marriage, I think we were both concerned about what it all would mean for our future together when her high school dropout and superannuated hippie of a husband who had always cocked his snoot at authority figures of every stripe, suddenly started courting the largest authority figure of them all. A lot of people wondered if it bothered me that my wife didn’t share what had obviously become such a large part of my life. Incredible as it might seem, my answer was usually and mostly, ‘No - not a lot and not very often.’ I couldn’t imagine that conversion would make her any more loveable or deserving of my devotion. As she was already the most honest, the least greedy and the most fair-minded person I knew, I couldn’t anticipate a pronounced increase in the morality department if she did execute a graceful triple-header into the Tiber and ‘came over’. Also helping us withstand the ‘disparity of cult’ in our home was the fact that as artists, my wife and I were routinely left to our own devices for great slabs of solitary time. That’s the only way that either of us gets our work done. So pronounced was both of our needs to regularly stand apart that we used to joke that being close to either one of us could sometimes be a pretty faraway experience. We never felt more useless and wasted than when one of us was dragged along as a mute appendage to some function or emporium which only fascinated the other person. To hector her about the Church would insult her intelligence and her integrity. I answered any questions she had about the faith and otherwise, bided my time, waiting for opportunities to plant seeds. She understood that it was having kids that accelerated my need for a more definite Christian affiliation and even honoured my decision by giving me a confirmation present of a beautifully illustrated book of Bible stories to read to our children. Though she wasn’t prepared to make such a move herself, she recognized that for me fatherhood was, in Samuel Johnson’s great phrase, ‘a time to be in earnest,’ and she welcomed that. My perfect attendance at RCIA classes was only marred once when our second child and first son was born on January 12th of 1984. In lieu of a note from my mom or my wife, I took Hugh along to church a few weeks later in a Snuggly just to prove I wasn’t playing hooky. As with my wife, I didn’t assume my commitment would automatically serve for my kids as well. I knew they would have to do their own examining and questioning and might even dawdle longer than I had in the anterooms of indecision. Rather, it was a matter of personal obligation. Forget what’s cool or easy or fun or sounds like the kind of thing kids want to hear; any father owes his children the most honest answers he can find to all the important questions. And I knew that I’d been stalling for decades on the most important question of them all. I already believed in Christ – and knew that with the tiniest bit of focused discernment I could give myself to Him – so what was I going to do about it? It was time to join a church. But which one? Canada’s largest United Church congregation was in London at that time and was rightly famous for the oratorical powers of its head minister, Maurice Boyd. That being the denomination of church I had fitfully attended as a youth, I checked it out first. There were three services there every Sunday and the sermons were as stimulating as a good university lecture, chock full of quotes from English mystics and preachers like John Donne, George Herbert, William Blake and Leslie Weatherhead. That got me reading the aforementioned writers and I was already familiar with ‘denominationless’ apologists like C.S. Lewis with his Mere Christianity and Malcolm Muggeridge who didn’t publish anything about his eventual leap across the Tiber until 1988. But even then it was particularly G.K. Chesterton and a handful of other Roman Catholic writers whose world view I found the most compellingly attractive and complete. I might have joined the United Church that year but something held me back. Though I couldn’t name it yet, there was always something crucial that was missing at those services; something more important than an intellectually probing sermon; something I wouldn’t discover until Maurice Boyd went away on his usual summer-long sabbatical and, repelled by the numbing tone and content of his substitute sermonizer (a woman, it so happened), I was driven into St. Peter’s Cathedral Basilica in downtown London one hot Sunday evening in August of 1983.  Jan Van Eyck (d: 1441): Altarpiece at Ghent Cathedral, Adoration of the Lamb, 1432. Jan Van Eyck (d: 1441): Altarpiece at Ghent Cathedral, Adoration of the Lamb, 1432. What did I find at St. Peter’s that night? I suppose the shortest answer (as I don’t remember anything about the homily; not even who gave it) would be that I found everything but the sermon. Though St. Peter’s is only classified as a minor basilica, I found a glorious, century old cathedral of sufficient architectural splendour as to inspire feelings of reverence and awe. The first thing that caught my eye, like something in a painting by Rembrandt, were the angled cones of light which poured in through the Catherine-wheel window of the west transept gable, tinting and spotlighting the parishioners below. The craftsmanship and artistry, the attention to detail, the heroic scope and lines of the place – all draw your soul upward and outward in a three dimensional prayer of love and praise. Nowhere else in town can you find such heroic stone pillars and archways, such grotesque gargoyles and such sublime statuary including an alabaster Pieta in the west nave; all of which effortlessly evoke a mood of deep reflection. Next to the Pieta is the original tombstone for Henry Edward Dormer, London, Ontario’s sole candidate for sainthood. I found kneelers in front of every pew and a service which required the entire congregation to spend about a third of the time on their knees. A revelation to one of my United Church background who’d never spent two seconds on his knees, I was astonished by how good it felt – how appropriate and necessary – to assume that posture in God’s house. Then there was the beautiful processing forward of the parishioners to receive the Eucharist. I loved the fact that they didn’t just sit there and take things in as if they’d walked into some celestial movie house but had to make a point of going forward to receive God. I remembered when my Mom had taken me to a Christian Crusade at the old London Gardens with evangelist Leighton Ford. There came the moment of the Billy Graham-style altar call when those – and only those – who felt they might be ready to convert were invited to go forward and stand beneath the dais where Mr. Ford preached. It bugged me for a couple of reasons, neither of which was perhaps fair. The action or the gesture seemed to be more about Mr. Ford than God; a sort of evangelical equivalent of a standing ovation commending the effectiveness of his preaching. And I felt sorry for all the previously converted believers who were now obliged to sit this one out. It suggested that conversion was this one-time action, the great climax of your search for God, and once you’d made that decisive move, that was it. From now on you should just come to church and sit there. It seemed all wrong and these Catholics had it right. They understood that when you’re in God’s presence, anyone who loves Him and worships Him will want to get up on their pins and go to Him. St. Peter’s was packed that muggy night even though this was the sixth Mass of the day. And except for 7 a.m. services on weekday mornings, the number of people who routinely turn out for all of the masses is never less than impressive to one who comes from a tradition of optional, not to say, lax, church attendance. If you didn’t turn up a half hour early for the Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve or the Easter Vigil, then you’d be standing in the aisles for the considerable duration of these festive blow-outs. I felt a little giddy after my first Christmas Eve service to spill out into the snowy city streets at one thirty a.m. as the bells in the tower peeled out the news of Christ’s birth. Couldn’t we get arrested for making so much noise? I’ve talked with people who attended the afternoon Mass in May of 1981 on the day St. John Paul II was shot. It was a working day but St. Peter’s was packed within an hour of the first news reports. One member at that gathering – an Anglican, actually, who’s since come over to Rome – told me he’d never felt the stalking presence of evil in our world so acutely as on that day. A Catholic woman told me she’d never experienced such a profound sense of solidarity with her Church and pictured storm-lashed lifeboats as she thought of the thousands upon thousands of simultaneous services being held all around the world at that moment. Fifteen years ago this spring as John Paul II finally lay dying in his apartment at the Vatican, I headed out to St. Peter’s late on the night before his death. I didn’t know that anything would be happening – only that it should be – and sure enough an all night vigil was underway in the Lady Chapel where I took my place kneeling beside dozens of other weeping and praying parishioners. Another bane of Protestant services which was nowhere to be seen on that hot August night was the moist-palmed welcoming committee just inside the main entrance. This was a huge relief as I’d always found such clammy encounters a distraction. Having to run a gauntlet of glib-talking, hand-shaking greeters minutes before I’m hoping to quietly commune with God was always an irritating ordeal. Membership in other churches was as readily proffered as a charge card in a department store. They’d sign you up coming or going. ‘Hello, stranger! Would you like to be registered as a preferred parishioner?’ No one made such overtures at St. Peter’s and when I made inquiries that very first night, I learned that I would have to attend and pass a six month catechism course before they would even think about letting me join. ‘Wow. Standards for membership in a church,’ I thought. ‘What a novel idea.’ Not knowing any Catholics personally, I had a volunteer sponsor assigned to me for the duration of the course. A little younger than me, Mark Nowicki was a Polish-Canadian cradle Catholic who was starting up a rug cleaning business and worked on an old one of mine from my study with such vigour that it more or less disintegrated. But I didn’t hold that against him. He was a good man. He accompanied me to every class and made himself available whenever I had extra questions or just wanted to talk about this ever-deepening process of spiritual initiation. We often met in a downtown coffee shop and loaned each other books. In one of our many talks, he told me that the only time he’d ever seen his father cry was the day they announced that Cardinal Karol Wojtyla had just been elected Pope. But back to that first night. No lurching or hand-wringing, no over-dressing or social fussing – the over-riding impression I received was that all of these people, the clergy and the laity, knew in their bones that they belonged to the Church and the Church belonged to them. And the heart of that knowledge, like the heart of their faith, was contained in the pulsing mystery of the Eucharist. I never tire of this most central of sacraments. In the three and a half decades since my first visit to St. Peter’s, I have found no common human activity more beautiful to watch than that quiet and respectful queuing up and shuffling along, the dispensing of the Host, the words, ‘Body of Christ,’ intoned a thousand times with never a mistake or hesitation, the answering, ‘amen,’ and the gradual, grateful dispersal back to the pews. There’s a wonderful story about Hilaire Belloc which perfectly (if a little vulgarly) expresses the unflappable confidence which Catholics have in their Church. It seems that Belloc was on one of his lecture tours in the United States and dropped into an inner-city cathedral for Mass. Blithely unaware of the local variations in the service, Belloc kneeled or genuflected according to the rite of his own home parish in Sussex, England. About two thirds of the way through the service, a priest approached Belloc and whispered in his ear, “It is customary at this point for our people to kneel.” Belloc not only refused to comply with this suggestion; he turned to the priest and whispered, “Piss off!” from which admonishment the priest backed away and explained, “My apologies, Sir – I didn’t realize you were Catholic.” As a convert it took me the better part of a decade to work up that sort of confidence about my place in the Church. As a trivial example of what I mean here, out of politeness I used to half-heartedly join in when rounds of applause for a choir or a visiting priest or a just confirmed child are offered up during Mass. I don’t any more. I know it’s not a serious point. It’s a matter of aesthetics and not ethics or theology. But I find it jarring. It takes me out of the moment to applaud human beings when I’m in God’s house and I won’t do it anymore, not even if a well-meaning priest should whisper in my ear about what is customary or appropriate. Thankfully that kind of confidence, that determination to carry out our mission in our own distinctive way remains very much in evidence today – both internally in the rites and practices of our faith and externally in our interactions with the world to which we stand as a sign of contradiction with a brilliance and a force that no other church approaches. If I had to boil it down to a single phrase it would be this: We are the Church that means it. And we mean it most of all when it comes to our positions regarding those acts and milestones which are the most meaningful of all – birth, marriage and death – or what the old newspaper editors used to call, hatching, matching and dispatching. Since the Reformation of the 16th century, the number of amoebae-like splits which the ever more narrowly defined breakaway churches have performed is boggling. For every coming together, there are a dozen fractures. One lot leaves because they want to change the liturgy; another wants fewer altar ornaments. This lot ordains practising homosexuals; or that lot heads off into the woods to invoke Pan or Isis or their inner children. Anybody with a cause or a condition has a church to themselves nowadays. So why does the Catholic Church still drive so many people buggy? Because this Church still stands as the most conspicuous bearer of those enduring standards which our world would just as soon discard but which rightly nag the human conscience whenever we’re reminded of them. Those standards include: a commitment to truth regardless of unpopularity or inconvenience; a conception of human nature and the roles of men and women which goes deeper than wishful social engineering; and an awareness of the sacredness and the potential for God’s redeeming love in every instant of human existence from conception to natural death. This incredibly tolerant culture of ours which prides itself on its openness, broad-mindedness and un-shockability, is never more offended than when someone is seen to be forming an opinion in adherence to Catholic principles. Why would you want to refer to the moral and spiritual wisdom of the ages? What could some medieval bozo like St. Francis of Assisi or St. Thomas More possibly have to tell us today? ‘Think for yourself, man!’ they self-righteously bark, implying that their own non-position of ever-shifting moral and philosophical relativism is the proud achievement of decades of fearless and lonely intellectual struggle – that the easiest and lamest thing to do in all the world is to work to discern the truth and then commit to live by it. ‘Of course, you oppose abortion,’ one of my favourite high school English teachers told me shortly after I came into the Church as we shared some beer in a South London pub. ‘Your Church tells you to, right?’ To his credit, he backed down on this cheap shot when I leveled him with a murderous glare and reminded him that he’d given me good grades for doing my own thinking when it came to digesting Shakespeare and William Faulkner. Why would I bring anything less to the Bible, to Papal Encyclicals or the writings of the Church fathers? But the condescending assumption, universally prevalent it seems, is that even the most capable student of English literature (or quantum physics, for that matter) is obliged to check his brain at the door prior to entering any Church. But as things turned out, in my experience, the truth has been precisely the opposite. I find that the Church and the last two Popes (before Francis the waffler) in their various encyclicals and books unfailingly help me to clarify my thought, to trace contemporary questions and issues all the way back to foundational principles, so as to most intelligently and comprehensively formulate my own position and speak an opinion worth airing. And this special genius for promoting discernment is hardly a new function. In olden times it was the Church alone which cultivated literacy, sponsored the work of artists and scholars and during the darkest depths of the middle ages, kept the flickering light of civilization aglow. I was never so completely at the mercy of whimsy and sentiment and the farcically crude intimidation of special interest groups – pernicious forces which are everywhere nowadays – than I was in the years before I joined the Church. The Catholic Church has always maintained that those supremely important occasions of hatching, matching and dispatching, are each of them moments when we have a special opportunity to honour solemn, binding contracts with God. As any parent in this abortion-riddled era realizes when they freshly behold their thriving, striving, endlessly beloved, but at one time perhaps inconvenient child . . . as any spouse knows who has worked through a season or 20 of discontent to find that new and infinitely deeper plateau of mature married love . . . and as any afflicted person who finds the grace and courage to weather a period when their radically altered or diminished life no longer seems worth living . . . these are all sacred contracts which, when honoured, carry enormous and unpredictable rewards – both in this life and the life to come. And then to top everything off, at the Easter vigil of 2015 – a mere 31 years after I came into the Church at the age of 31 – my wife surprised us all by becoming a Catholic. (So let's not have any talk that I browbeat her into the Catholic fold.) There were a few indications along the way that some changes were underway in her heart, such as the time she suddenly and passionately sprang to the defense of John Paul II when her brother had been slagging him. But no, I didn’t see it coming. Then three years ago to mark our 40th anniversary, my wife and I renewed our vows at a special Mass in the Marian chapel of St. Peter’s. Carrying as they do a suggestion that marriage is not necessarily for life, renewal ceremonies of this sort are not something that a lot of Catholics go in for. And had we been Catholics when we first tied the knot on December 28th, 1977, I doubt very much we would have felt any need to make this public act of re-commitment. But 43 years ago we were both, to varying degrees, agnostics, and so were married at a civil ceremony at Toronto City Hall. We would’ve married locally but London City Hall was closed for that entire week between Christmas and New Year’s when we wanted to piggy-back our nuptials onto the general merriment of the season. At an Opus Dei Lenten retreat in the spring of 2000, I had scored a copy of Frank Sheed’s, To Know Christ Jesus and just melted when I read the conclusion to his account of Mary and Joseph’s wedding in Nazareth: “How far the wedding feast of Mary and Joseph resembled that of Cana, we can only guess – we simply cannot see either Mary or Joseph putting on any very spectacular show. But one thing the two feasts have in common – Christ was present at both of them! No royal wedding had ever had a glory to compare with that. The poorest Catholic can have it now with a nuptial Mass.” I have always regarded our marriage as the supreme blessing of my life even if, contractually speaking, it was a strictly civil matter. Utterly enchanted by Sheed’s illustration of what a true nuptial Mass can be, I wistfully accepted that while the Church recognized the validity of our City Hall union, my wife and I would never enjoy the privilege of being able to exchange our vows in the presence of Christ. And now -owing to a series of developments that I intermittently prayed for but never felt confident would come to pass – we have. And perhaps the sweetest surprise of them all is that at a time when our babies have all been launched into the world and one might have expected things to settle down a little, sharing this faith together at last has brought a great revivifying sense of purpose and renewal to our union.  This essay, slightly tweaked and updated here, first appeared in Canadian Converts Volume II, 2018, published by Justin Press. Also from later that same year, check out this Hermaneutics essay The Francis Defect which outlines the, I trust, temporary challenges of being Catholic in the age of Pope Francis.

4 Comments

Bill Craven

4/2/2020 09:19:51 pm

Thanks for the latest testimonial in your Hermaneutics.

Reply

Max Lucchesi

5/2/2020 07:27:55 am

Herman, I agree with Mr. Craven. Christ did only give us one church. It was called Christianity, despite it's Schisms, different roads, wrong turnings and no doubt to many of us it's various perversions. Let's not forget that the first great Schism in 1054 AD was the Bishop of Rome, finally after 500 years of agitation breaking away from the rule of the Patriarch of Constantinople, religious head of the Roman Empire. Thus it became the Roman Catholic Church.. Of the four original Episcopal Sees: Jerusalem founded by James the brother of Jesus, Alexandria by Mark the Evangelist, Rome by Simon Peter and Paul and Antioch founded by Simon Peter. Only after the Council of Ephesus c.449 was Rome granted the recognition of being 'The Apostolic See' not for it's greater sanctity but for it's greater recognition. Rome had been the capital of the Roman Empire for well over a thousand years, Constantinople for less than seventy. Ireneaus c.130-c.200 and Tertullian c.130-c.240. had begun to define the authority of the various bishops, as the Apostles themselves had founded in all 25 major bishoprics from present day Bulgaria to the Malabar coast of India, all of which, of whatever variation of worship were under the authority of Constantinople. The common article of faith which identified and bound them together was the Nicene Creed.

Reply

6/2/2020 03:38:58 am

I have commented positively in the past on Herman as an important local historian. This article is a valuable picture of the Christian life of London since the 1980s, and it provides a valuable reading list of books by Chesterton and (chiefly) other Englishmen. Some of the material is idiosyncratic,but it is a genuine history of the ecclesiastic habits of a London person and many of the people.he knew.

Reply

Max Lucchesi

6/2/2020 09:00:29 am

Herman, as you know I am against self congratulatory Catholicism, religion should be private and personal. However as I seem to always be chiding you, I offer you this story. It's about that wonderful actor Alec Guinness, and as you have never mentioned it I assume you dont know it. Guinness had an unhappy, fatherless and peripatetic childhood, though several unsuitable step fathers did come and go. As a young man he dabbled with Anglicanism, Buddhism, Socialism even flirting with Catholicism. When in Hollywood he had accompanied Grace Kelly to Mass. His only son Mathew aged 11 contracted Polio, Alec went into a Catholic church and prayed that if his son was cured he would allow him to become a Catholic if his son wanted to. Mathew against all the odds was cured and Alec enrolled him into a Jesuit Academy. In 1954 Alec was making the film version of Father Brown on location in Burgundy. After a days shooting he would often return to his lodgings still clothed in his character's Soutane and Capello Romano. One evening a small boy took him by the hand and accompanied him to his lodgings all the while chatting happily. It made a deep impression on him, he said of the meeting " without knowing me, but as I was dressed as a priest the boy trusted and knew he would be safe and looked after". He began to seriously learn about Catholicism. His son Mathew when he was 15 years old asked to be converted, in 1956 Alec himself was received into the church. Have I presumed you knew nothing of this? As usual do with it as you will.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed