LONDON, ONTARIO – I learned a valuable, lifetime lesson from an act of literary spoliation I unconsciously committed around the age of 18. Blown away by the magnificence of The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, I immediately and successively raced through every novel of Mordecai Richler’s that I could lay my hands on and within a couple of months – surprise, surprise – I had utterly OD’d on the man. While I still objectively acknowledge Richler as one of Canada’s bravest and most wickedly funny writers, I was never able to take up any of the subsequent novels of his later maturity – I’m talking here about everything that followed St. Urbain’s Horeseman – without accompanying pangs of queasiness and ennui that were entirely owing to my past impetuosity as a reader and had nothing to do with Richler’s very considerable skills as a writer. The lesson I learned nearly half a century ago is that greedily burning your way through anyone’s entire oeuvre like a pack of cigarettes lit end to end, is no way to treat an author and will almost certainly put you off a good thing. I have never repeated that mistake with any writer. No matter how beloved a new enthusiasm might be, how eager I am to expand my experience of a new pleasure, I will trade it off with a different writer and if possible another genre before taking up another work by the same hand. And I am happy to report that in this much more sensibly paced way, I have just completed a most unhurried ramble of ten years duration through Anthony Trollope’s (1815–82) six linked novels that make up what most readers and critics consider the crowning achievement of this remarkably productive Victorian literary factory, The Chronicles of Barsetshire.

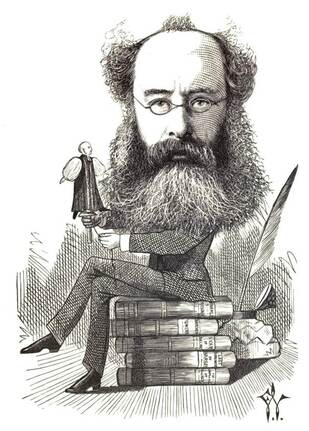

The component novels of this series which explores the operations of an Anglican Church diocese in mid-19th century Britain, are all set within (or in one case, on) the border of the imaginary county of Barset. In order of both their composition and the grand narrative’s chronology, the six books are The Warden, Barchester Towers, Doctor Thorne, Framley Parsonage, The Small House at Allington and The Last Chronicle of Barset. And I do hereby solemnly declare that the Barsetshire series is everything that its champions proclaim it to be; a miraculously detailed, character-rich, sepia-toned portrait of an ancient and once sufficient church that is starting to lose its coherence and authority at the hands of disputatious factions within. No one sang Barsetshire’s praises more insightfully than Monsignor Ronald Knox (1888–1957). This devoted son of an Anglican bishop became an Anglican priest himself until he could no longer abide the disintegrating liberal drift that Trollope had recorded 50 years before and hurled himself over the Tiber in 1917; becoming one of the mainstays of the Catholic revival in the first half of the 20th century. Knox wrote about Trollope and Barsetshire frequently and his brilliant 1936 satire, Barchester Pilgrimage, gives us the stories of the descendants of Trollope’s original characters who must contend with forms of ecclesial erosion that their parents and grandparents never dreamt of. In 1958’s Literary Distractions, a collection of his essays that was published the year after his death, Knox ruminated on the everlasting attraction he felt for Trollope’s meticulously assembled world: “That, after all, is the secret of Barsetshire; that is why it appeals to a nostalgic age like our own. It symbolizes the twilight of an ancien regime; a twilight which seemed to its contemporaries as though it might, perhaps, be only cloud. The reforms which belong to the first half of the nineteenth century had left their mark on English society, but as yet only an uncertain one, like ripples on the surface of a clear pool. Outwardly, the governing forces of English life seemed to remain what they were – the landed gentry, the Established Church, the two ancient universities; and yet that world of privilege was threatened. For a moment, when he sketched out the plot of The Warden, Trollope half believed that he was on the side of the reformers. But when, in the first chapter of Barchester Towers, the Government went out just in time to secure the appointment of a Whig bishop, the die was cast; from that point onwards the series is an epic of reaction; all Trollope’s heroes are Conservatives, all his villains are Whigs. In the political novels [of Trollope’s six-volume Palliser series], politics are only a game; in the “clerical” novels all is in deadly earnest – every contested election, every vacant prebend [the parish appointment from which a cleric derives his salary], begins to matter. He could not save the old order of things, the world of privilege he so intimately loved, but his sympathies have embalmed the unavailing conflict.” A contemporary of Charles Dickens and William Thackeray, Anthony Trollope was well into his 30s before he published his first book and into his 40s before he realized anything resembling a literary income. And yet he turned out to be one of the most prolific writers in that very well-upholstered period of three, four and even five-volume novels. What makes Trollope’s productivity even more remarkable is that for most of his life he had to fit his writing in on the side, rising most mornings at 5:30 to give the first three hours of his day to writing before heading off to his full time job as an upper level manager with the Post Office. “A small daily task if it really be daily, will beat the labours of a spasmodic Hercules,” he observed. Trollope wrote his novels by timetable and never missed a deadline. His average, carefully calculated output saw him blacken 40 pages (with 250 words per page) each week. He usually had more than one book on the go simultaneously and never took a break between books. His unvarying goal was to produce at least 10,000 words per week and over half a million words per year. And that, I repeat, was the minimum. He regularly exceeded it. By the time of his death, his name had appeared on almost 70 different books – 47 novels, five collections of short stories, five travel books, three biographies, a translation of The Commentaries of Caesar and a refreshingly no-nonsense autobiography with precious little about his private life and unlimited shop talk about the writing biz. Though he started out as a junior-level clerk, Trollope's efficiency and drive soon lifted him to the management level. Among many other accomplishments, he invented the red pillar-style mailbox (along with double-decker buses and phone booths, one of three red emblems of British life beloved by postcard manufacturers); an innovation which greatly eased the accessibility of service in rural areas where the public previously had to rely on far-flung postal sub-stations. He often travelled in his Post Office work; around Britain, of course, but also to some rather exotic outposts of the British Empire. Whether travelling by boat or by rail, through monsoons or blistering heat, he continued to faithfully churn out his 40 pages per week. And all of that globe-trotting and sightseeing supplied him with impressions, vistas and locales that made their way into his books. Diligent, shrewd and inclined to be blunt when dealing with underlings less competent than himself, Trollope’s day job gradually helped him to temper his fierce independence and impatience so that he developed consideration and a tolerance for differing views. Indeed, the span of Trollope's human understanding, encompassing all classes and conditions of men, would become one of the hallmarks of his writing. He developed an appreciation for cussedness and orneriness, for the reserved and the shy, for the isolated and the crazy, for personal idiosyncrasies and weaknesses, and came to understand the million tiny contracts and concessions we all must make in order to function in society. No novelist was better equipped to juggle the enormous casts of characters who populated his books or to understand the inner institutional workings of parliament and the church and a host of less rarefied offices and workplaces. So profound was his understanding of the clerical mind, that many Barsetshire fans are a little crestfallen when they learn that its author was not particularly given to religious raptures of any kind; that, in the words of his finest biographer N. John Hall, Trollope was nothing more spiritually adept than “a nominal latitudinarian, tolerant Church of England adherent, more worldly than otherwise.” Charles Dickens was the grand panjandrum on the literary scene in Trollope’s lifetime, casting a shadow over every other scribbler by dint of his unparalleled popularity. Trollope acknowledged Dickens’ precedence – how could he not? - but always thought his writing was too sweepingly broad. He saw Dickens as a gifted creator of grotesques and caricatures, always ready to ladle on the sentiment or any kind of preposterous twists that would move his fantastic stories forward, sacrificing verisimilitude to the machinations of plot and the big impression. He had much greater admiration for Thackeray (whose first biography Trollope wrote), George Eliot and Charlotte Bronte – at least in Jane Eyre. And this generous appreciation of the artistry of certain sisters of the pen seemed to carry over into the complex and full-blooded female characters he created in his novels; starkly contrasting with the simpering and anemic virgins that Dickens was all too prone to manufacture and set up on pedestals. Having pulled himself up from humble, lonely and vaguely disgraceful beginnings, Trollope knew poverty and the hard grind of the poor just as surely as Dickens – he just didn’t get hysterical or maudlin or embittered about it. (Indeed, Anthony Trollope literally died laughing; a fatal stroke silencing his paroxysmic enjoyment of the best-selling comic novel, F. Anstey's Vice Versa.) While his father Thomas started out his married life as a well-connected Chancery barrister, a string of rotten luck and his own paralyzingly depressive temperament soon scuppered all that and the Trollopes were living on Skint Street by the time Anthony was born. Originally one of seven children, only Anthony and one older brother, Thomas Jr., would outlive their parents as that all-too-common Victorian stalking horse – tuberculosis – picked off his other siblings one by one. And in the depths of his family’s destitution, it was Trollope's resilient, distracted and often physically absent mother, Frances, who worked like a dog as a writer of primarily comic stories to try to keep hearth and home together. Some 35 books were credited to Fanny Trollope in her day and her greatest success, Domestic Manners of the Americans, can still be found in print today. But it was for the most part pretty thankless and barely remunerative job-work that characterized her lot as a writer. I’m sure her experience directly inspired her son to be so calculating about what it would take to make his own way as a writer. And I also sense her example played no small part in his creation of so many admirable and capable female characters. After several decades of comparative neglect, there was a revival of interest in the Barsetshire and Palliser novels during World War II when that more graceful society Trollope depicted with such love was being obliterated at an alarming pace and people suddenly had need of good fat books to while away the hours they spent hunkered down in tube stations and backyard Anderson shelters. Then about 25 years ago the Folio Society roughly quadrupled the common understanding of his legacy's extent by publishing a gorgeous and comprehensive collected edition of his literary remains. Pathetically enough, the latest challenge to Trollope's reputation comes from nothing so real as an all-obliterating Wehrmacht or a scarcity of books but from the vainest of chimeras dreamed up by ideologically hopped-up academics who hate to read outside the rut of their own politically poisoned specialty. Anthony Trollope runs afoul of more strident contemporary tastes because he hobnobbed with the elite and frequently conveyed the charm and enticements of a wealthier milieu without a trace of the now-required self-loathing or resentment. He loved belonging to clubs and hunting for foxes and guilelessly (and, as it turned out, correctly) assumed that his readers would enjoy reading about such escapades as well even if they couldn’t afford to partake themselves. It is part of Trollope’s glory that he took in so much more of the passing scene all around him than other writers of his day, had a much broader understanding of the ways in which human lives could play out and wasn’t so inclined to fog up the telling of his tales with unwarranted sentiment or damning moral judgements. As a word magician Trollope may have lacked some of the pyrotechnics of a four-star wizard like Dickens but in his sturdy, at times ironic and quietly elegant prose, this reader at least finds himself in the presence of a Victorian voice he instinctively trusts and is eager to spend more time with. I’ve already acquired all six Palliser novels and look forward to reading them in the decade ahead.

1 Comment

SUE CASSAN

8/7/2019 11:32:58 am

You’ve really done me in this time. I was getting ready to tackle Kristen Lavransdottir. Now I’m thinking I must get at the Barchester series I’ve been promising myself. I want to turn the clock back to summers consisting of a hammock and lemonade. Now I have to fit in work, entertaining a dog, and keeping up to improving videos On YouTube. Take me back to the days when you had to cut the pages of the novel yourself before you could read it.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed