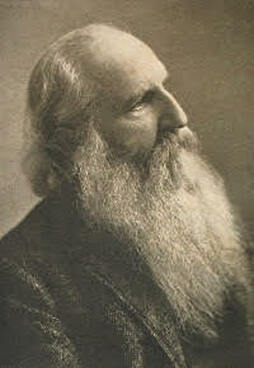

Dr. Richard Maurice Bucke (1837–1902) Dr. Richard Maurice Bucke (1837–1902) LONDON, ONTARIO – It was primarily through the machinations of Sir John Carling (1823 – 1911) that shrewd London politician, brew master and businessman, that London was chosen as the site for a new provincial lunatic asylum. Carling held seats in both the Provincial Assembly (as the minister of public works) and in the Federal House of Commons until such dual representation was disallowed in 1872. With this kind of double clout, Carling was able to effect the transfer in 1870 of a makeshift asylum in a converted barrack at Fort Malden in Essex County to the new London Asylum for the Insane which was built on a 300 acre parcel of land three miles east of the old city – a parcel of land which Carling owned and sold to the province at a tidy profit. Carling’s timing was impeccable. Did he sense a coming boom in madness? Prior to 1870 there was one asylum in the province: the Toronto Asylum which maintained branch hospitals in Fort Malden and Orillia. Three autonomous regional asylums were to be built that decade – first in London, then Kingston and Hamilton. By the end of the 1880s almost 20% of the provincial budget was going into the maintenance of its new and extensive asylum system. In Victorian Lunacy, a study of late 19th century psychiatric practice, S.E.D. Shortt writes that this figure “was almost twice the combined provincial expenditure on penal institutions, general hospitals, houses of refuge and orphanages. The asylum, in effect, held pride of place in the provincial welfare system.” Another way of measuring this sudden boom is by counting the number of people this system served. London journalist and historian Archie Bremner wrote in 1897 (displaying an officious certainty that today seems almost charming): “The first mention of an insane person in the London district was in 1837, when provision was made for the maintenance of a lunatic at a private house.” When Bremner wrote that sentence 50 years later, the London Asylum had 1,200 inmates under its care. The actual construction of the Asylum was a rush job and a botch up. Once the plan was hatched to empty out the asylums in Fort Malden and Orillia, Carling’s Department of Public Works put the pressure on to get the Asylum built more quickly than was advisable. Kivas Tully, an architect and engineer with the Department of Public Works came up with a design for the project and recommended that $500,000 be set aside for construction costs. This figure was slashed in half by provincial treasurer, D.D. Wood, who was not of the belief that lunatics would either require or appreciate buildings of architectural distinction. Thomas Henry Tracy was a 21 year old architectural apprentice who’d just completed five years training with William Robinson, founder of London’s most prominent architectural firm. Tracy no sooner landed his job with the Department of Public Works then he was sent back to his hometown for his very first assignment – to act as clerk of works for the Asylum project. This was a challenge that would’ve given pause to the most seasoned of pros. For someone of Tracy’s inexperience it was too much, too soon, too fast and too cheap. He had to oversee the construction of the 610 foot long main building and an assortment of secondary buildings which included two workshops, a bakery and storehouse, two barns, two stables, a two-storey home for the superintendent joined to the main asylum by a covered walkway and two entrance lodges. Tracy also had to tend to the matters of drains and fences and could never be on site as much as he wanted to be because of the need to produce regular progress reports and estimates to his superiors at the Public Works and he also had to come up with working drawings for all the different phases of construction. Though Tracey was allowed to hire an on-site foreman to oversee the project, it wasn’t enough to ensure that the job was done right. Work on the project began in June of 1869. By mid-November of 1870 the first patients were being admitted from Fort Malden and Orillia. By early December the Asylum’s first superintendent, Dr. Henry Landor, was firing off a list of complaints to John Carling, demanding immediate and comprehensive improvements to a facility that had only been operational for three weeks. Among the more pressing problems cited were poor ventilation and drainage, inadequate heating and sewage facilities, a leaking roof, warped windows and floors made of too-soft wood. London’s Liberal newspaper, The Advertiser, had itself a field day reporting on John Carling’s ‘Botched Building’ which also happened to be the biggest building in the entire western half of Ontario.  The old London Asylum for the Insane The old London Asylum for the Insane Now that our region’s still-resounding madness boom is housed in new quarters down St. Thomas way and the derelict grounds and buildings of the old Asylum and its architecturally innocuous successor, the London Psychiatric Hospital, have been sold to Old Oak Properties for redevelopment as something called a “transit village,” the most prominent monument to madness that London retains is the legacy of Dr. Richard Maurice Bucke (1837 – 1902). A born adventurer, the amount of interests and experiences Bucke crammed into his 65 years almost beggars the imagination. Born in England, the son of an emigrating Anglican clergyman, Bucke spent his childhood at Creek Farm, situated on a tract of land east of London not far from the site where the London Asylum would be built in 1870. Bucke received no primary schooling but instead was set loose in his father’s extensive library. At the age of 18 Bucke left home and spent the next three years drifting all over the western United States, occasionally working at the kinds of jobs that 12 year old boys dream of – as a railway man, a Mississippi riverboat deckhand, a driver in a wagon train. He concluded this period in his life with an unlucky stint of panning for gold on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevadas in 1857. He and two other prospectors were attacked by Indians, disease and the elements. One partner died from blood poisoning, the other from the effects of exposure when they were trapped in Squaw Valley by an unusually harsh and early winter. Bucke had to eat his pack mule to stay alive and finally staggered into sanctuary at an isolated mining camp on the other side of the mountains where his left foot and part of his right were amputated for frostbite. So much for the physical life. With no formal schooling to his credit, Bucke switched gears and spheres and now enrolled at McGill Medical School where he earned numerous academic prizes prior to graduating in 1862, then crossed the Atlantic for post-graduate studies in London and Paris. In January of 1864 Bucke came back to Ontario and took over his brother’s medical practice in Sarnia, got married and began serious baby production (he and his wife Jessie would raise seven children), was appointed superintendent of the Hamilton Asylum in 1876 and came back to London the very next year as superintendent of the London Asylum. An iconoclast who significantly humanized the Asylum environment, Bucke removed bars from all the windows except those on the most violent wards, gave his patients healthful employment on the Asylum’s working 200 acre farm (this simultaneously minimized the institution’s drain on the public purse and improved the patients’ daily bill of fare), all but banned physical or chemical restraints, developed Asylum theatre troupes and sports teams who would play to or against groups from the city, arranged music recitals and readings for the patients and had his friend and hero Walt Whitman stay with him for three months at his house on the Asylum grounds. For the most part Bucke approached his patients not as demons or lepers but as troubled human beings whose fundamental needs – nourishment, society, work and recreation – weren’t at all different from the needs of the general population. Whenever possible he erased that invisible but impenetrable line that customarily separates caretakers from their charges. Maintaining that equality, that openness, becomes very difficult over a sustained period of time. The chaos becomes too threatening. Even Whitman – celebrated as the most democratic of poets – reached a limit during his three month stay in London. In July of 1888 he wrote: “The wonderful phenomena of lunacy – what does that mean? Has it a physical basis? or physical entanglements? or what: It is a lesson to see Bucke’s asylum at London – the hundreds on hundreds of his insane. I used to wander through the wards quite freely – go everywhere – even among the boisterous patients – the very violent. But I couldn’t stand it long – I finally told Doctor I could not continue to do it. I think I gave him back the key which he had entrusted to me: It became a too-near fact – too poignant – too sharply painful – too ghastly true.” The only black mark against Bucke’s professional record concerned his prolonged practice of gynaecological surgery as a form of psychotherapy; a rather extreme measure for which Bucke caught a fair bit of flak from his medical colleagues toward the end of his life. While such a practice does seem to confirm our darkest doubts about Victorian attitudes to sexuality, it also seems startlingly at odds with Bucke’s worshipful admiration for the poetry and philosophy of Whitman. How were his poor female patients supposed to “sing the body electric” once they’d had their main fuses surgically removed? The late Susan Maynard, a yoga instructor and Bucke biographer, could not excuse or justify such practices but believed they grew out of Bucke’s pioneering investigations into man’s nervous system. “Dr. Bucke was one of the first people to recognize the existence of two nervous systems with two separate functions,” she told me. “He labelled these the cerebro-spinal nervous system and the great sympathetic nervous system. He didn’t understand yoga or any of the practices of the east but he was convinced of the connection between what’s happening in the body and what’s happening in the mind and the emotions. Most of the changes he introduced in the day-to-day life of the Asylum were to help relieve stress and anxiety – to get his patients to truly relax. Bucke felt that what happened in the nervous system affected the mind so that if he thought the organs that had the most sympathetic nerves in them were diseased – those were the cases where he’d undertake gynaecological surgery. He certainly didn’t perform these operations on anyone he didn’t feel, rightly or wrong, had such a disease.” As the son of a clergyman, Bucke was practically obliged to reject Christianity as a young man, yet evinced a marked spiritual hunger virtually all of his life. He underwent a spontaneous mystical illumination at the age of 36 when, revved up by a long evening of reading romantic poetry with some friends in London, England, during the hansom cab ride back to his lodgings he was suddenly consumed by what he described as “a rolling cloud of flaming Brahmic splendour.” After this fleeting visitation Bucke knew, “that the cosmos is not dead matter but a living Presence, that the soul of man is immortal, that the universe is so built and ordered that without any peradventure all things work together for the good of each and all, that the foundation principle of the world is what we call love and that the happiness of everyone is in the long run absolutely certain.” In the wake of his illumination, always set apart by Bucke as the single most important minute of his life, his intellectual career progressed ever heavenward and inward (they were one and the same to him) culminating with the publication of Cosmic Consciousness in 1901, one year after the sudden death of his beloved son Maurice, who is the recipient of the book’s heart-breaking dedication: “How at that time we felt your loss – how we still feel it – I would not set down even if I could . . . Through the experiences which underlie this volume I have been taught, that in spite of death and the grave, although you are beyond the range of our sight and hearing, notwithstanding that the universe of sense testifies to your absence, you are not dead and not really absent, but alive and well and not far from me at this moment . . . Do you read from within what I am now thinking and feeling? If you do, you know how dear to me you were while you lived and how much more dear you have become to me since. Only a little while now and we shall be again together . . . So long! dear boy.” Cosmic Consciousness, still in print today (its phenomenal shelf life greatly assisted by a long and favourable mention in William James’ classic study, The Varieties of Religious Experience), is a lengthy investigation of Bucke’s own illumination and the similar experiences of 50 other people; both contemporaries (who in many cases are allowed to speak in their own words) and historical figures to whom Bucke ascribes such experiences. As the highly conspicuous and publicly accountable superintendent of an insane asylum, he was a sitting duck for the scorn and outrage of all those determined to disallow his testimony. I believe his experience and its value to him even while I doubt his need to recast the spiritual history of the world in such a way that it can all be seen as evidence to support his new theory. Any author who steals Christ from the Christians and Buddha from the Buddhists and says, in effect, “Oh no, you had it all wrong; these were early cases of Cosmic Consciousness,” is biting off more than any immortal can chew. Bucke believed that modern man was on the evolutionary threshold of a heightened, more mystical awareness and that the cases of illumination he cited were harbingers of that future. I don’t share his optimism but will spare you my thesis that in fact the inverse is true; that mankind has been fearlessly backsliding in this regard for at least 400 years. I find the book a fascinating, maddening and deeply moving document; a final summing up of all Bucke’s most deeply held convictions and hopes; an almost desperate contrivance for some kind of faith by an ageing man of science who was too sensitive to ever be satisfied with a completely material explanation of life and the universe. A rather goofy Canadian movie was made about Bucke and his relationship with Walt Whitman in 1990. Written and directed by London born filmmaker John Harrison, Beautiful Dreamers starred Colm Feore as Bucke and Rip Torn as Whitman. The film is set during the summer of 1880 when Whitman paid his extended visit to the Asylum and is the story of the rekindled passion between Dr. Bucke and his wife, Jessie, which the American poet fans to flame. In point of fact, the closest the Buckes ever came to divorce was during and after that visit. Jessie cordially detested Whitman and let it be known after he finally departed that the ragged, bohemian oaf must never darken their door again. Bucke lashed back in a letter to his wife which made it clear where his ultimate allegiance lay: “You may be sure I shall never try to get Walt Whitman into a house where he isn’t wanted . . . If all the world stood on one side and Walt Whitman, in general contempt on the other, I hope I should not hesitate to choose Walt Whitman.” If I had to choose a side in such a standoff, I’d sidle up next to Jessie. Bucke’s feverish and unceasing adulation of Whitman really could get unseemly and it must have been humiliating for Jessie to watch her husband trailing after the great one all summer long like some besotted puppy. In Bucke’s Life of Whitman, the first, ‘authorised’ and largely dictated biography of the poet (dictated by Walt, that is) Bucke becomes irritatingly shrill in singing the great one’s praises; admiring Whitman’s “physical and moral purity,” the “clean smell of his breath,” and credulously passing on Whitman’s claim that his ears were so finely tuned that he could actually hear the sound of growing grass (a conceit Roy Wood took up to marvellous effect in The Move’s I Can Hear The Grass Grow). “I have never known him to sneer at any person or thing,” wrote Bucke, thankfully not being present when Whitman sneered about another of his fawning ebullient fans, that this one “out-Bucked even Bucke.” Though he was revered in his day by artists I esteem such as G.K. Chesterton and Ralph Vaughan Williams, Whitman isn’t my favourite poet by a long shot (too much compiling of inventories; not enough intuitive perception) and – to these nostrils at least – he doesn’t smell particularly clean at all. He smells like a braggart and a con man, inventing myths about the several children he fathered to disguise his homosexuality, posing for his authorial photo with an artificial butterfly ‘perched’ on his finger by means of a ring, cultivating and manipulating a small army of sickly attendants and followers who would place him on a higher pedestal than Jesus Christ and then get laughed at for their efforts. If Whitman was a con man, then Bucke was a rube. While his naiveté may have worked to his own degradation in his relationship with Whitman, it also accounted for a large part of his greatness in other matters. What is required of a man who would throw himself into the harsh physical life of his 20s, roving at will under limitless skies and courting adventure wherever he went? In a word, what’s required is trust. Trust in himself and his faculties, and a trust that anyone he meets will share his sincerity and good intentions. It was that same trust which drove him to write Cosmic Consciousness. He knew what his illumination meant to him and worked all his life to share its importance with others – sceptics and doubters be damned. And he trusted and believed in the goodness of his lunatics – perhaps the most feared and despised of all segments of Victorian society – and in so doing, won them much freedom and enabled many of them to become better and more complete people. Bucke’s trust and sincerity may occasionally look foolish to we citizens of a more cynical age. But what has haunted us about him for 117 years is the suspicion that London’s only documented mystic was something more rare and sublime than foolish; that, agnostic or not, this was some kind of holy fool. Bucke’s death was something perfect; perhaps a perfect joke but a huge and cosmic joke beyond all human laughter; a joke fit for the downfall of one of the Olympian heroes. The following account is taken from George Acklom’s introduction to the 1946 edition of Cosmic Consciousness. “On February 19th, 1902, after coming home with his wife from an evening spent at a friend’s house, Bucke stepped out on the verandah before going to bed to have another look at the stars which, as it happened, that night were exceptionally brilliant in the clear winter sky, slipped on a patch of ice, struck his head violently against a verandah pillar and dropped. He was taken up dead.” I defy you or Homer or the Brothers Grimm or P.G. Wodehouse to invent more perfect or poetic circumstances for the death of a Canadian mystic.

1 Comment

Susan Cassan

27/3/2019 07:50:01 am

What an amazing man. Unlike Whitman, who handed back the key, Bucke was able to stay at his post, running what must have been a difficult institution with the humanity that few if any others possessed. How wonderful that London should be the home of a mystic like William Blake who saw angels. It gives us hope that this supremely pragmatic corner of the universe has magic in it after all.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed