Orlo Miller (1911 - 1993) Orlo Miller (1911 - 1993) LONDON, ONTARIO - This is a dedication to London historian, Orlo Miller, which I composed for my 1989 collection of essays, Towards a Forest City Mythology. “Because of Orlo Miller’s books of London history, I carry around a ghost map in my head; a sort of transparent grid which I can lay over the city as I move through it and see what’s no longer there. I see where a drunken nineteenth century mayor drove his buggy down a sidewalk and I see Dr. Neill Cream dragging his first murder victim to the back shed behind his shop. I see the east end typhus and cholera dumps where hundreds of new Irish immigrants took their first and last sightings of London and I’m present at the Donnelly trials where six murderers brazened their way through to a verdict of ‘not guilty’. I’ve attended regimental balls at Eldon House and helped pass buckets of water that didn’t do very much to contain the great fire of 1845. No other writer has evoked these visions and experiences with half his clarity and power, nor his abiding sense of justice. “Orlo’s books have helped to make me a lover and a fighter where London is concerned. No one knows better than he what a mixed blessing it can be to really know where you stand. There’s the firm joy of rootedness, the fondness of recognition, the occasional delight of surprise. There’s also rage and disillusionment in times like these when progress and history don’t march in step but come at each other face to face.

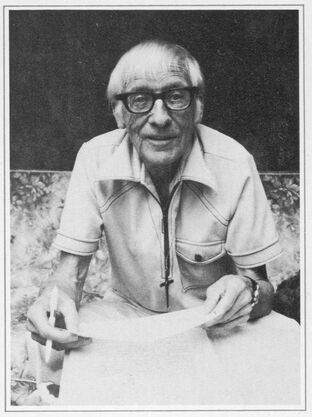

“For all he has done throughout his career in revealing and exalting ourselves to ourselves, this book is gratefully dedicated to Orlo Miller.” When he died four years later at the age of 82, I was glad I had saluted my favourite London historian in this public way. How often upon learning of a death do we rue our failure to tell someone what they meant to us? Orlo never knew much in the way of material ease; a fate which probably isn't so bitter if your not-so-lucrative work has been taken up with enthusiasm and esteem by even a middling sized public . Of the seventeen books Orlo produced in a writing career that spanned more than six decades, he is most widely remembered for two. The first of these, originally published in 1962 and never out of print since then, is The Donnellys Must Die, the first objective (and indeed, sympathetic) account we have of the notorious Donnelly murders just up the road in Lucan on February the 4th of 1880. Prior to Orlo's reassessment of that tragedy, the so-called 'Black Donnellys' had always been depicted as blood-thirsty hoodlums who deserved everything they reaped when they were murdered at the hands of their vigilante neighbours. Conducting his research seventy years after those murders when many of the old vigilante names were still printed on roadside mailboxes, some diplomacy and tact were required. Even so, Orlo received more than one death threat but pushed ahead with a book he saw as 'long overdue'. His wife, Maridon - also his first reader and shrewdest critic - completely shared his commitment to the Donnelly project. Orlo told me that after his researches were complete and he sat down to write, he had to take twelve consecutive runs at the book's magisterial first chapter in which all the tale's components and themes are carefully laid out. (I no longer recall if it was Orlo or me who likened that process to the meticulous planning and sequencing of a fireworks display.) Once Maridon declared that his first chapter was done, Orlo said that the rest of the book came pouring out in a torrent. By tracing the family's tale back to their roots in Tipperary, Orlo was able to show that the Donnellys had originally come over to Canada specifically to avoid the Irish 'troubles' and had then wandered into the very same trap when those old religious animosities re-constellated themselves all along the Roman Line outside of Lucan. This courageous and revolutionary book turned an old myth inside out and paved the way for the dozens of adaptations of the Donnelly story which have been produced - in books and on the stage - since then. While Orlo was asked to write the entry on the Donnellys for The Canadian Encyclopedia, his name rarely appears in more academic reference books. The Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature, for instance, lists everyone who ever had two words to say about the Donnellys except Orlo. The reason for this snubbing is no great mystery. Orlo was never affiliated with a university department and he paid a price for this in terms of acknowledgement from academic and critical communities. Of course, this rankled but Orlo usually managed to accept it philosophically. I'll always remember how wonderfully he laughed - for the better part of a minute it seemed - when I told him the story of a colleague of Malcolm Muggeridge who was bemoaning his lack of advancement in the civil service. "Could it be," he asked Malcolm, "that I'm just not licking the right boots?" Most particularly Orlo was a little ticked at James Reaney Sr. to whom he'd loaned all of his laboriously procured Donnelly research materials and received minimal acknowledgement for his assistance when Jamie went on to write his celebrated trilogy of Donnelly plays. Late in his life I wheeled Orlo like Banquo's ghost into a seminar about writing local history that was being held at the Art & Historical Museum and on their panel of experts was Jamie and Peter Colley who'd also worked up a Donnelly script that was widely produced. To his immense credit, Jamie gestured to Orlo in his wheelchair and informed the gathering that here was the man who really started it all. And (though he wasn't around to see it) in The Donnelly Documents: An Ontario Vendetta (published by the Champlain Society in 2004), Jamie committed his commendation of Orlo's seminal work to print. Less controversial but an equally great work (and certainly a trickier kind of book to write well) was Orlo's last book from 1988, This Was London, which was reissued in the last year of Orlo's life as London 200: An Illustrated History. (That re-issuing, by the way, happened entirely at the behest of historian, librarian and publisher, Ed Phelps, who sought to alleviate the poverty of Orlo's dotage.) The challenge in writing a generalized city history is similar to that of a juggler who has to keep a dozen different plates spinning away on the tops of sticks. Pay too much attention to one plate and you'll start to lose all the others. The cast of characters is enormous but each one has to be sketched out both briefly and indelibly. You can't take a really deep dive into anything and must somehow contrive to combine a lightness of touch with authority. And all the while that you're flitting about from this subject to that incident to that character, a larger corporate narrative has to emerge as well. It would have been a Herculean task for a man half his age but Orlo pulled it off beautifully. I remember Chris Doty telling me how impressed he was when researching London arcana at the Central Library, to look around at students beavering away on local history projects with a pile of different texts to hand and unfailingly digging into the Orlo Millers most of all. There may be other books which cover different aspects of London history in more depth but as a general history of a rich, sprawling and multi-faceted city, Orlo's final book was a grand summing up of all the stories he'd gathered about this town he loved so dearly. I always regarded Orlo as the patron saint of London freelancers. He did contract work for The London Free Press in the 30s and 40s which supplied fodder for A Century of Western Ontario (1949) his rambunctious history of journalism's pioneering days in London. And in the 60s he became an Anglican minister, which fueled his definitive history of St. Paul's Cathedral entitled, Gargoyles and Gentlemen (1966). But significantly, neither of those affiliations turned into full blown careers for this writer who always insisted on going his own way. Once he told me - with pointed emphasis suggesting I should attend closely and learn something here - that part of what drew him to London's oldest newspaper and London's oldest church, was the fact that between the two of them, those institutions gave him unimpeded access to the most complete records in the city. Including his extensive work for CBC Radio and locally produced radio and television plays, Orlo cranked out more scripts than could now be counted. Ten of his stage plays were locally produced and he and Maridon were driving forces in the 40s and 50s when the London Little Theatre Company was one of the most dynamic theatre troupes in the country. And - perhaps constituting a sort of bookend to that dedication which opened this essay - Orlo wrote an introduction (we fittingly called it an 'Overture') to Curtain Rising, my history of theatre in London which was published a couple months before he died and probably enjoys the honour of being the last thing he published in his lifetime. In 1991 artists Stuart Reid and Doreen Balabanoff were commissioned by the city to design and erect a monument called People and the City which celebrated the contributions of fifty-one different Londoners from all walks of life. Originally the only rule regarding commemorated figures was that they had to be dead. I talked Stuart and Doreen into bending that rule for Orlo (they'd already bent it for researchers Murray Barr and Helen Battle), explaining that Orlo had announced three years earlier that he wouldn't be writing another book and how could we overlook all that he had done for the city? As Stuart said in a short speech on the day of the unveiling (for which both Orlo and Dr. Barr were in proud attendance), "It would be cruel to punish these people for their longevity." Photo credit: David Hallam

7 Comments

Nancy Poole

6/7/2021 08:23:51 am

Thank you, Herman. Orlo was a cherished friend and supporter and I miss his brilliant historic writing and mischievous sense of humour.

Reply

Ninian Mellamphy

6/7/2021 01:51:25 pm

Herman Goodden is a gift to us his readers because he is the type of local historian who will not let us forget the likes of Orlo Miller, whom so many of us knew as a journalist in The Free Press and as a friend in the Baconian Society. Let us hope that Herman's jottings will inform our children and grandchildren to whom the death of Orlo in 1993 may seem like long ago,

Reply

Susan Cassan

6/7/2021 02:07:34 pm

This is a great tribute to Orlo, to whom all Londoners owe a debt, for his magnificent work preserving our history.

Reply

Jim Ross

7/7/2021 08:09:45 am

I am always deeply moved, Herman, by the breadth of your knowledge of this city and its people. When I read your recollections, I can think of London as good soil - if I close my eyes...

Reply

Graeme Hunter

7/7/2021 11:03:01 am

Thanks Herman. What a terrific site. Your intelligent prose is as delightful as it is unusual.

Reply

Dan Mailer

10/7/2021 11:54:49 am

Good one Herman!

Reply

Bill Craven

29/7/2021 09:20:52 am

Orlo was a fellow priest with me at St. Paul's Cathedral, and I heard him proclaim from the pulpit that he had been converted by reading the Apostles' Creed. Bishop Luxton ordained him without degrees. Elizabeth, Orlo and I went crypt-crawling and found a human bone.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed